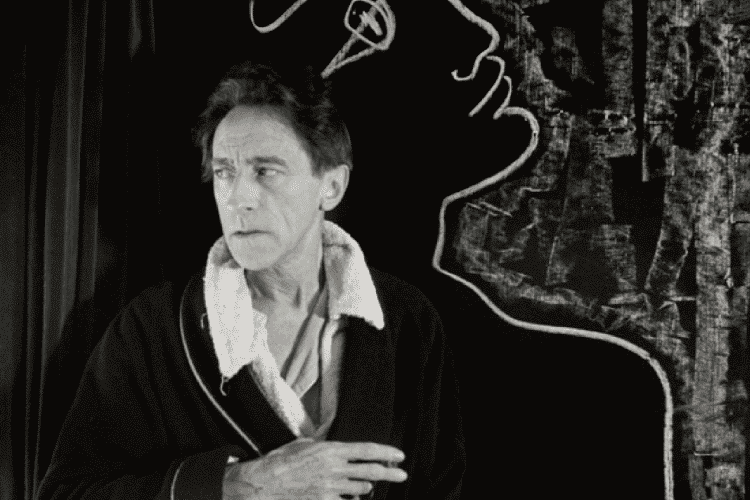

Appearing as an unnamed Poet who is mysteriously dropped into contemporary France from the 18th century, Jean Cocteau’s final film work announced him as the art icons par excellence.

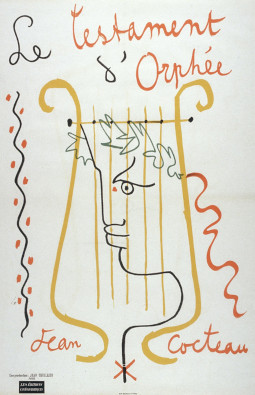

Many of us remember where we were in January of 2016, when that turbulent year kicked off with the news of David Bowie’s death. The Starman had left the terrestrial plane to perhaps return to a home planet in a galaxy far, far away. His parting gift was a final record titled Blackstar, which he had released only two days prior, on his 69th birthday. Fans quickly ascertained that much of Blackstar, including its lead single and video “Lazarus,” addressed what he knew was his impending death. While the whole album and its timing was characteristically Bowie in its ability to surprise, he wasn’t the first nor the last artist to release a self-written elegy. Jean Cocteau had done it in 1960, with his final film, Le Testament d’Orphée, created three years before his death.

Jean Cocteau was your icon’s icon. An influencing force on an immeasurable number of cultural titans, the reverberations of his life and work can still be felt today. Born in 1889 Cocteau’s extraordinary trajectory saw him cross paths with everyone from Marcel Proust to François Truffaut, Coco Chanel to Kenneth Anger. His work was radically human and often explored his same-sex desires, opium addiction, and heartbreak. Cocteau was fascinated with classical mythology, particularly that of Orpheus and Eurydice, and revisited this inspiration several times throughout his oeuvre.

For many reasons, many of them stemming from his sexuality–Cocteau was never ‘closeted’ in the sense that we would describe it today—he was often caught in the crosshairs of the Parisian cultural and social scene. André Breton in particular found the autobiographical aspects of his early film-making to be vulgar (he would refer to Cocteau’s first film as ‘le sang menstruel d’un poète’.) Cocteau referred to himself as ‘The Poet,’ and his work in each medium as ‘poèsie graphique,’ ‘poèsie de théàtre,’ and so on. He once said that his films were poetry written with the “pen of light.”

By the time he made Le Testament d’Orphée, attitudes perceiving self-referential work as vulgar had more or less faded. He had no formal diagnosis of anything, but decades of opium addiction, an already frail constitution and hard living were starting to slow him down. Cocteau knew he did not have much time left.

Le Testament d’Orphée is uniquely specific to Cocteau’s legacy in the sense that it doesn’t hold up when viewed without prior knowledge of its director’s life and career or without already viewing the first two entries of his Orphic Trilogy, Le sang d’un poète (1928) and Orphée (1950). It is atmospheric, cerebral and very, very mysterious—partially a showcase of filmmaking techniques that an inexperienced Cocteau improvised in his previous works, partially an expansion of his lifelong discourse on the nature of poetry, poets, and love. He would rewind and slow shots to show people leaping out of the water and flying through the air; in Testament, these techniques allow the laws of nature to be defied as Cégeste emerges from the sea and a hibiscus flower is crushed and reassembled.

Unlike his prior films, he casts himself as the main character, appearing as an unnamed Poet who is mysteriously dropped into contemporary France from the 18th century. He is guided through several scenes which hearken and reference his past and present relationships and works. The cast is a who’s-who of the Parisian cultural illuminati, who appear uncredited: Jean Marais, Yul Brynner, Maria Casarès, Pablo Picasso, Françoise Sagan, Charles Aznavour, and Jean-Pierre Léaud make appearances.

Jean Cocteau was and is still considered an iconic Parisian, which makes his decision to set Testament on the Côte d’Azur all the more meaningful. Cocteau’s presence remains scattered along the Riviera: the cities of Villefranche, Menton, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, and Cap d’Ail all boast chapels, amphitheaters, marriage halls, homes and murals that the Poet himself designed and painted in his golden years.

Cocteau knew that the Côte d’Azur was the perfect location for a film whose ultimate goal is to meditate on the gray areas of humanity, creativity and poetry. Legend has it that in the 16th century, in what was then a region of the world regularly caught in a back-and-forth between France and Italy, a man passing through stated that a certain city within this territory was so-called because it was ‘ni ici, ni là’ (neither here, nor there). This was Nice, whose name seems to have been chosen for the multilingual puns it can deliver.

Jean Cocteau was and is still considered an iconic Parisian, which makes his decision to set Testament on the Côte d’Azur all the more meaningful. Cocteau’s presence remains scattered along the Riviera: the cities of Villefranche, Menton, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, and Cap d’Ail all boast chapels, amphitheaters, marriage halls, homes and murals that the Poet himself designed and painted in his golden years.

Chloë Cassens

But ultimately, what this visitor may not have realized in describing the then-ubiquitous changes in border is that he would be summarizing one of the defining qualities of the region. The Côte d’Azur is and has always been a place overlaid with a thick layer of mystery and the unexplainable—an easy mix of qualities to lead one towards exploring their own spirituality, religious beliefs, and mortality.

Knowing of Cocteau’s obsession with Orpheus and Eurydice, it’s fitting to see a major example of his work emerging from these depths. While Orpheus tragically cannot help but to look behind him to see if his Eurydice is following him out of the Underworld, Cocteau had one eye ever pointed towards the past and the other towards the future. A future where he has ceased to exist as a person, but lives on as an idea and a memory.

Orpheus and Eurydice were doomed to part where the veil between life and death was at its thinnest. Perhaps the Côte d’Azur was the half-way point of Orpheus and Eurydice’s journey—local lore posits that the reason for the exceptional sweetness of Menton’s citrus is because Eve tossed a lemon to the side there on her exile from Eden. One of the recurring motifs in Testament is a hibiscus flower that magically dies and revives, petals disintegrating in the Poet’s hand, only to re-form again and again. “The original sin of art is that it wanted to convince and to please, like flowers that grow in the hopes of ending up in a vase. I made this film without expecting anything other than the profound joy that I felt in making it,” wrote Cocteau in an essay about the film.

Jean Cocteau’s character dies and comes back to life more than once in the film, but at its end, he chooses to show himself fading away, leaning against a rocky mountain. As he disappears, a convertible full of young people careens down the road: a new generation coming in to be forgotten or cement themselves as Riviera legends. At the end, only the landscape will remain. In the “ni ici, ni là.”

Foot Note

This Saturday, July 5th, Chloë Cassens will host a screening of Le Testament d’Orphée at the Philosophical Research Society in Los Angeles. PRS was founded in 1934 by Manly P. Hall, a philosopher and author and is one of LA’s best kept secrets—a centre for the study of esoteric wisdom, rare film screenings and lectures.