“My artistic evolution is about getting close to my own body.” Based in Brooklyn, the 26-year-old painter Emil Sands—known for his oddly dark coastal scenes—has created an artistic language based on embodiment and vulnerability.

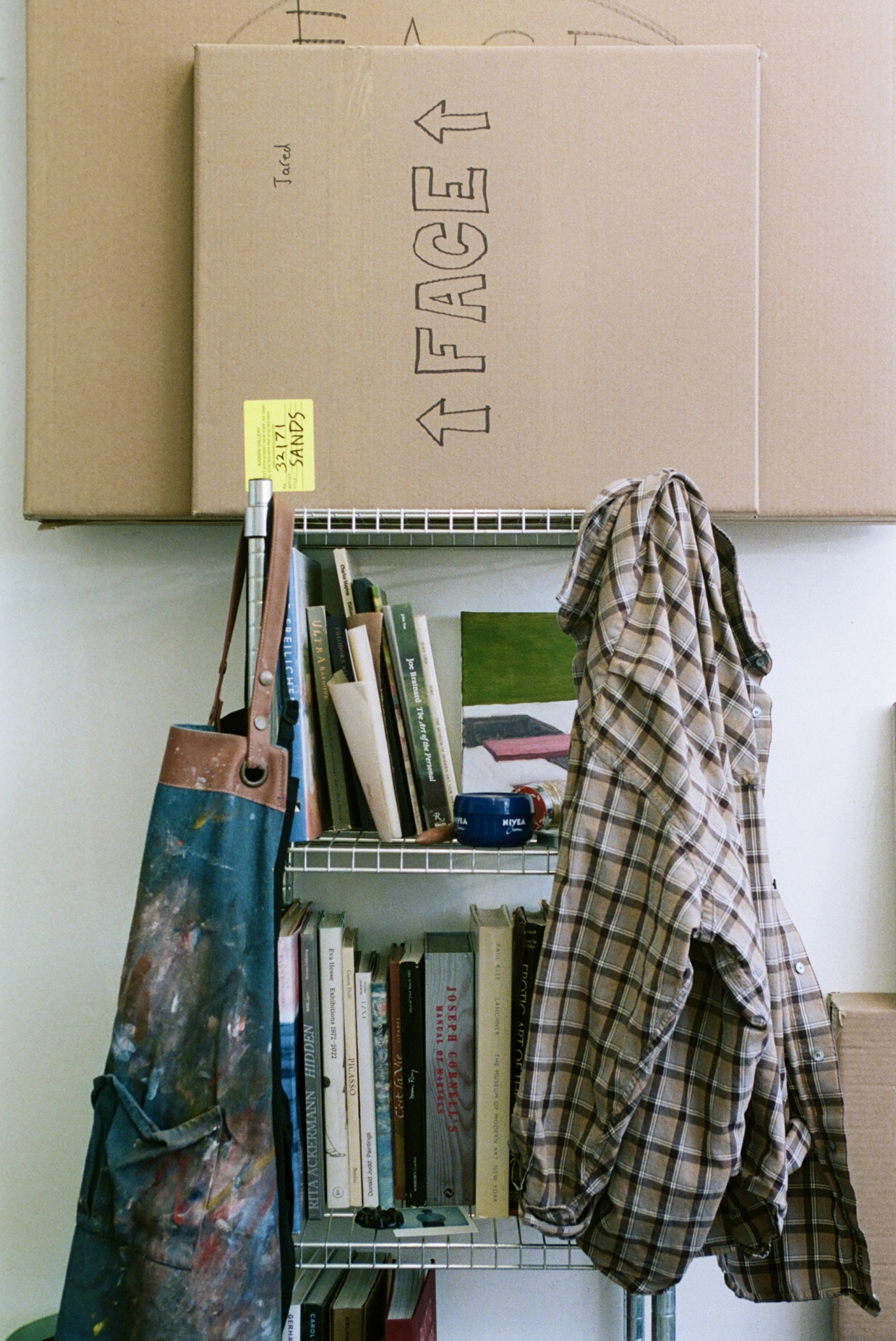

The Williamsburg studio of the London-born painter Emil Sands is filled from floor to ceiling with the artist’s latest creations: vast seascapes and rocky coastal scenes in which figures stand tentatively on beach shorelines. In saturated hues of azure and turquoise blue, the works vibrate with the intense heat of summer; we feel the warmth of beachgoers’ skin as they stand close to cool waters. Created for his first solo show Salt in the Throat at Kasmin Gallery in January of this year, the 26-year-old Sands is now working towards his first UK debut: a three-person group show at Victoria Miro, London, followed by a solo show at Victoria Miro, Venice in the new year. For an artist who only returned to painting seriously three years ago, his work is making big waves in the art world.

Speaking in person, Sands informs me that painting is, in fact, only half of his schedule right now. “I’ve got two jobs—or two non-jobs you might say” he jokes, with an air of self-deprecation. “In the morning I write, usually from 6am until midday. In the afternoon I paint, typically until 7 or 8pm.” Beyond establishing himself as an emerging artist, Sands is working towards his first book—a memoir which is set to be released next year (by Scribner in the US, and Picador in the UK). It came off the back of penning a piece for a class while he was a visiting fellow at Yale, but was then published by the Atlantic last year: Society Tells Me to Celebrate My Disability. What If I Don’t Want To?’ The unflinching essay offered insight into growing up with hemiplegia, or hemiplegic cerebral palsy—a neurological condition that affects half his body. Broken down into two parts, the impact of the condition becomes clearer: hemi, means “half,” and “plegia”, connotes stroke or paralysis. And although Sands explains that the severity of the symptoms has diminished significantly since childhood, the condition nevertheless shapes his relationship to his own body, as well as his outlook and creativity. “Writing and painting are quite intimately linked for me, as both are centered around the body,” he tells me. “What I’m thinking about when I write, definitely feeds into what I’m painting that afternoon. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that my paintings are becoming more narrative.”

Ambivalent feelings towards the body—in all its powers and limitations – underpins both Sands’ writing and painting. “A lot of the scenes I’m painting, especially of groups, remind me of times when I felt that I couldn’t participate. My own worries about my body would get in the way” he shares. But despite this reality, Sands’ still struggles with presenting himself as disabled. “I’m deeply uncomfortable with labels” he tells me. “And how labels can be co opted as a form of marketing tool, or end up stymieing artists. But at the same time, my cerebral palsy is undeniably a part of my life. It shapes the work I create and how I perceive the human body – my own body and the bodies of others. But you could also argue that labels like being white, middle class, or the fact that I grew up with dogs are just as integral to who I am,” he jokes.

Sands attributes the writing of the Atlantic article—which applied candour and nuance to the experience of having a disability—to a new era of personal and creative growth. “The article was the beginning of a process of self-acceptance” he reflects. “It looks at my upbringing with a disability and those feelings of being hyper self-conscious in my own body.” Yet the very thing Sands was once trying very hard to conceal, or “mask” amongst his peers, has now become a starting place for creative expression. “Not to sound too American about it, but I’m on a journey when it comes to accepting my own body,” he adds. “My artistic evolution is about getting close to my own body. It’s a kind of healing process. The act of painting itself is extremely physical, which is one of the things I love so much about being a painter.”

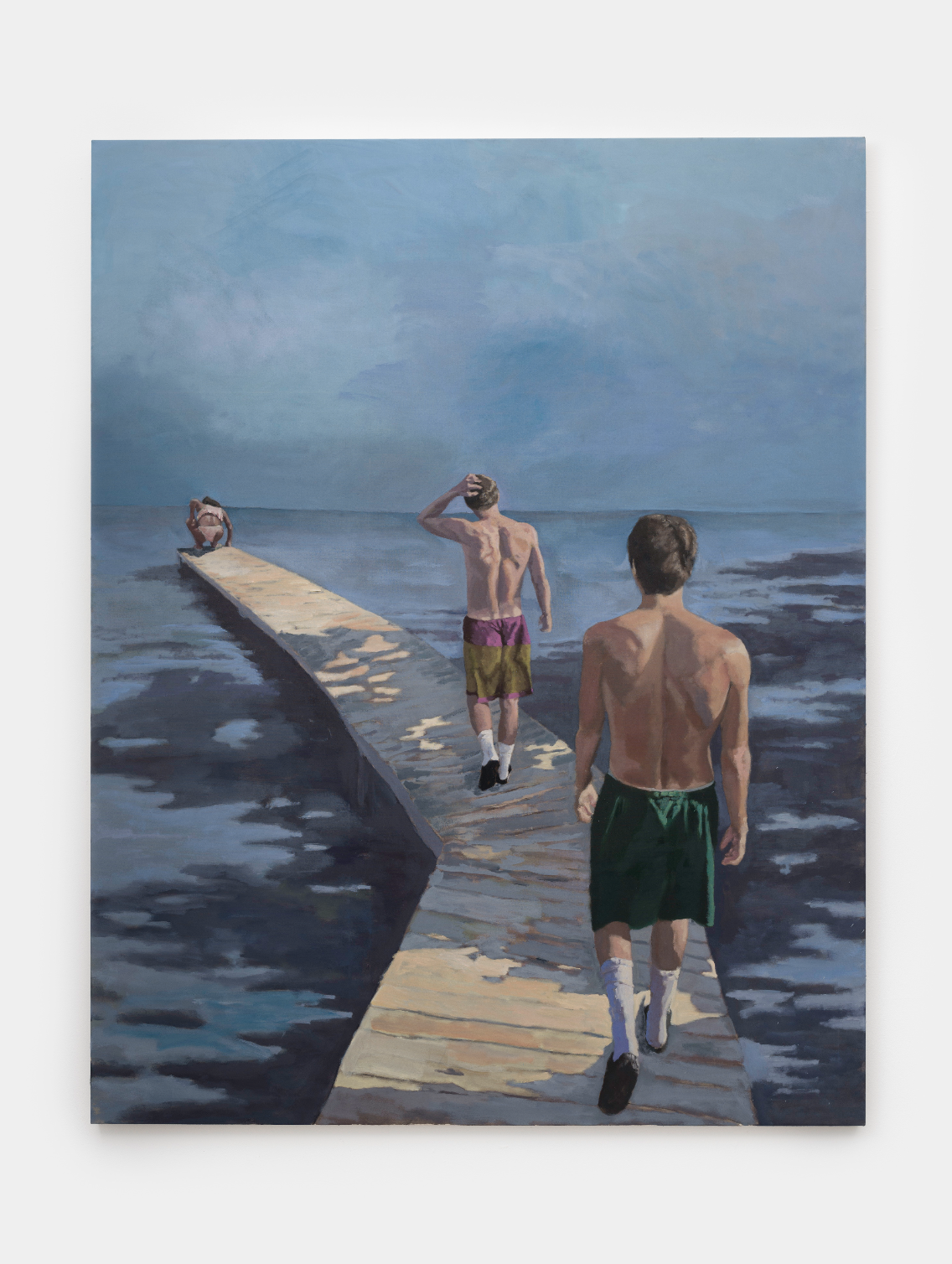

Echoing the contents of his prose, Sands’ paintings appear to ruminate on the physicality and psychological experience of embodied masculinity. As seen in works such as Lawn Party, The Invitation and The Last Holiday, he magnifies and accentuates the sinews and tonality of muscle, an attention to detail that reflects Sands’ own acute self-consciousness towards bodies in general. “My process draws from many things, but usually it’ll start with an observation, or something I’ve noticed in another person and which I’ll proceed to fixate on.” Sands explains. “I’ll notice the way someone holds their own body, their posture, or the way a hand falls on a hip. But it nearly always begins with an initial moment or movement—a charged bodily moment in a landscape.”

The weighted figures in his paintings take on a quasi-sculptural and statuesque quality. In this sense, his razor-sharp bodily observations reference a long-lasting academic interest in classical antiquity, a subject he studied at postgraduate level before returning to painting. “I understand renderings of the body in ancient art intimately well. I feel close to them, because I’ve studied them and lived with them.” He goes on to explain that the statues of classical antiquity resonated with him because of contrapposto,a pose in which a figure stands with most of its weight on one foot, causing the shoulders and arms to twist off-axis from the hips and legs. “I remember seeing ancient Greek statues as a teenager, and noticing that the contrapposto way of standing resembled how I feel most comfortable standing,” he explains. But unlike representations of the male physique in classical antiquity, Sands isn’t interested in creating perfected, beautified renderings of the body. “I want the bodies I paint to feel really fleshy and alive, rather than idealised . The bodies I paint are of real people doing real things.” The figures in the foreground of Sands’ paintings walk along shorelines, stand in shallow waters, or peer out into the distance. They are ordinary, and, for the most part, unaware they are the subject of voyeurism.

Sands’ willingness to be vulnerable lies at the heart of his creative ventures. At first glance, his scenes evoke a dreamy, escapist quality that belies the darker undertones of his ongoing ruminations. Hinting towards this personal journey, the works serve as both an interrogation and liberation of the body. Elusive and easy on the eye, each work conjures a tangible sense of lightness and play – a subtle reminder perhaps that not all of life’s joys are beholden to the constraints of the body.