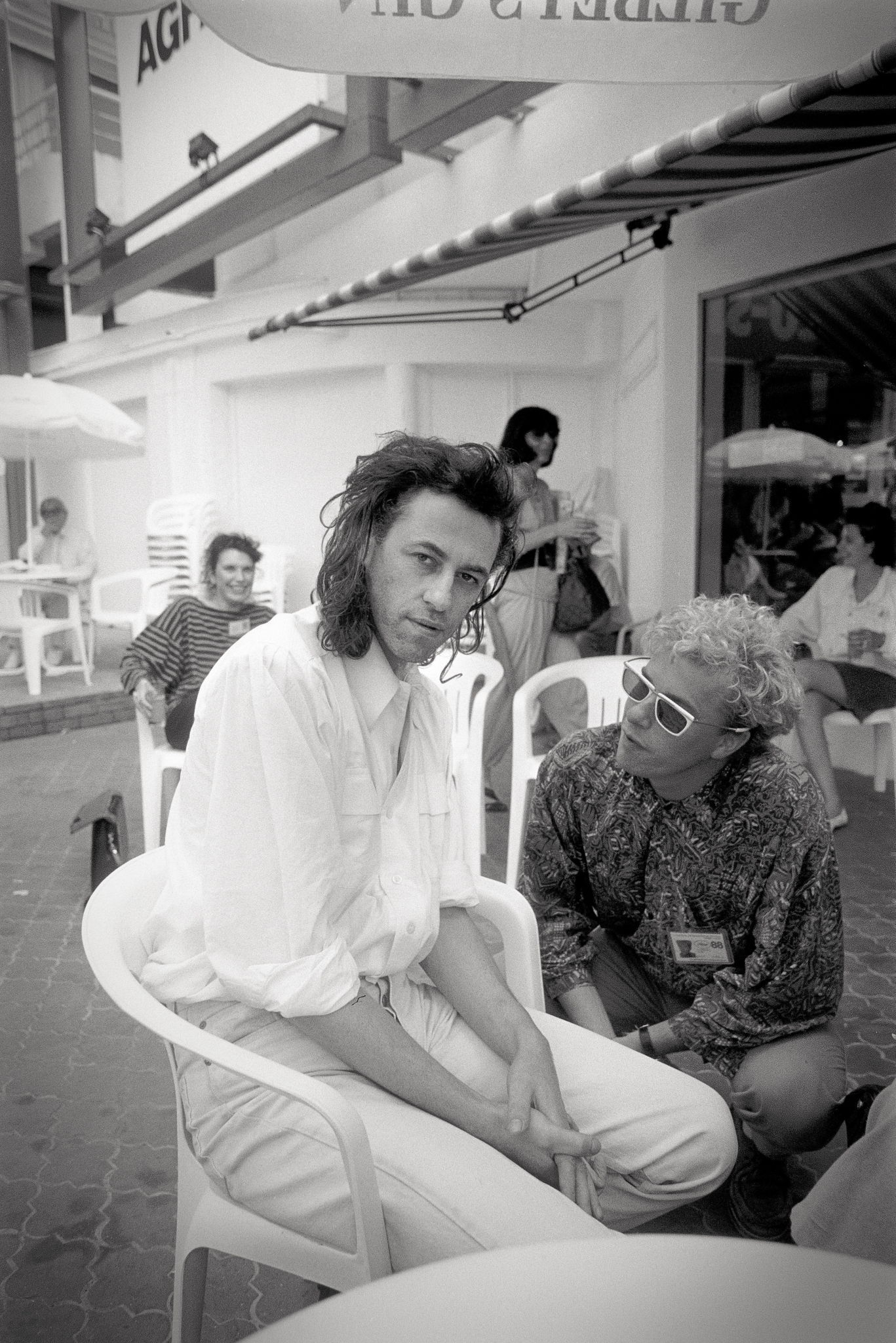

“I like my photographs to tell their own story,” says Derek Ridgers, a mug of jet-black coffee in hand, staring at a picture he took at the Cannes Film Festival in 1988. The shot is of legendary photographer Helmut Newton, surrounded by fellow photojournalists on Carlton Beach, squinting down at a medium format camera pointed directly at Ridgers. “I was watching him taking photographs and at one point he said, ‘You’re so close to the model, why don’t you get in the picture yourself?’ So I did.”

“It’s more interesting if it takes place in the viewer’s mind,” he continues.

“My explanation for my photographs isn’t going to be much better than yours.” It’s a fair point. But still, it’s hard to look at a photo taken by Ridgers—known for shooting everyone from punks, gangsters and porn stars to filmmakers, F1 drivers and heavy rockers—and not find yourself itching with intrigue. His photo of Newton, for example, suggests the existence of its twin: the shot that Newton is taking of Ridgers. “I never saw the photo he took of me,” Derek says, before adding, playfully: “It might have been a ploy…I was photographed by a couple of well-known photographers, and I don’t think I’ve ever seen any results.”

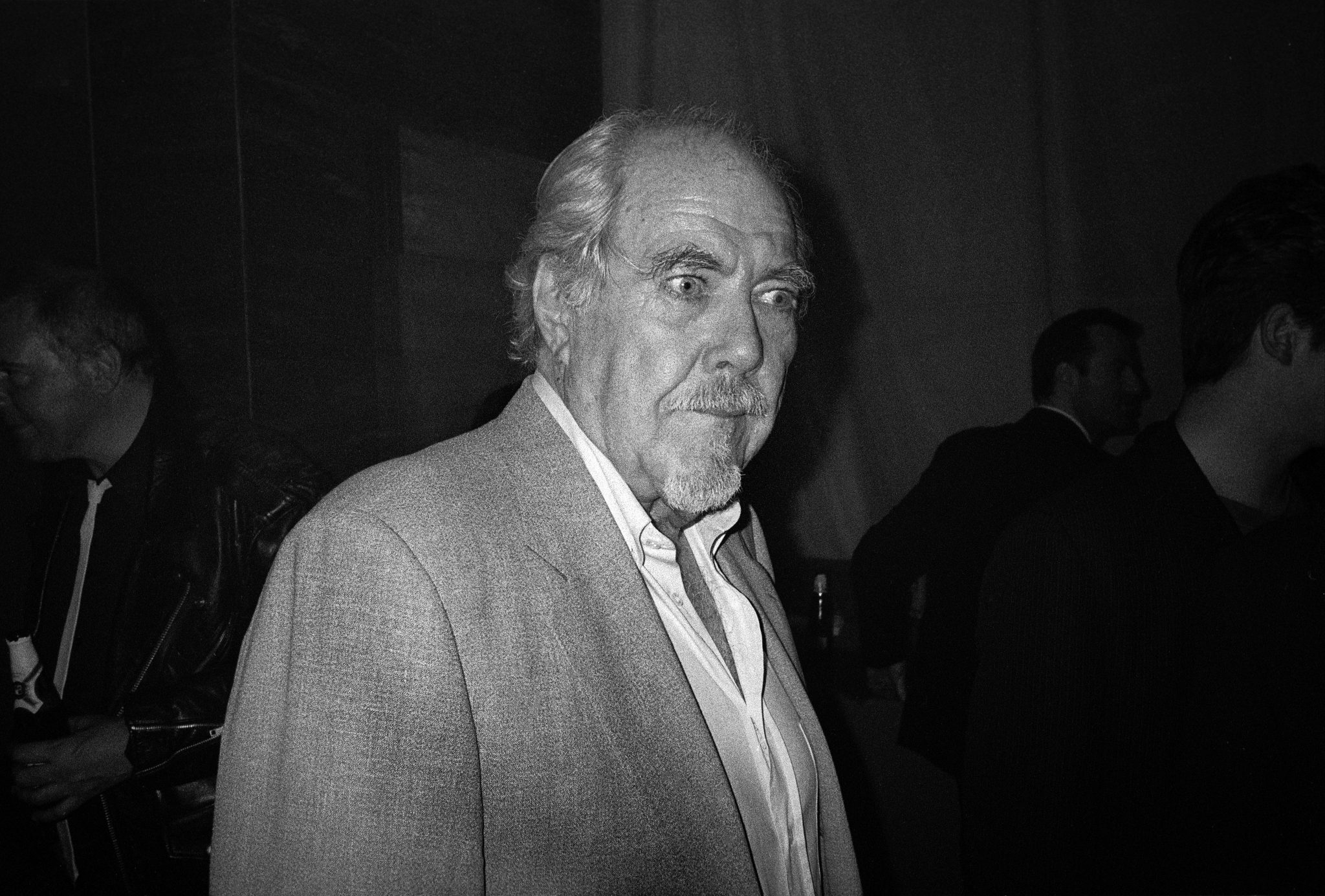

Despite what he says, Ridgers seems to have a story about just about everyone from his time shooting the film festival, which he attended regularly over the 1980s and 90s for publications like NME and Time Out. Spike Lee? “He wasn’t particularly friendly, but, then, I don’t expect people to necessarily be friendly.” Robert Altman? “I shot him at the Trainspotting party… he’s got the thousand-yard stare.” John Hurt? “[he was] going to have a big party in one of the villas overlooking the bay. I knew it would be the kind of party I was going to have to gatecrash.”

For Ridgers, Cannes was never really about films. “Why would you sit inside watching movies when it’s that hot, and that brilliant outside?” he says. Over two decades spent shooting the festival, he only ever watched two: Stan Lathan’s Beat Street and December Bride by Thaddeus O’Sullivan, an old friend from art school (which is why, he clarifies, he went to see it). The rest of the time was spent, in his words, “photographing the circus”—wandering around the festival chasing moments—unscripted and unforgettable. His adventures sometimes crossed over into Cannes’ underbelly, where French adult video journal Hot Vidèo were presenting their own coveted porn award, the Hot d’Or (a cheeky spin, of course, on the Palme d’Or), at the same time that the film festival was taking place.

Less glamorous? Maybe. But no less exhilarating. And it speaks to the joyous sense of mischief with which Ridgers moves through Cannes; a restless curiosity that seems allergic to the velvet ropes of celebrity culture. Sometimes he was invited. Other times, he wasn’t. But the lens doesn’t care. It only asks: is it interesting?

We sat down with Ridgers to discuss his first visit to the Cannes Film Festival, how Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up influenced him as a teen, and the stories behind some of his most iconic Cannes photographs.

It was for NME, in 1984, to take photographs of Afrika Bambaataa. It was the premiere of the film Beat Street, which was one of the first films about hip-hop. I was backstage somewhere, not very far from the Palais du Festival, and I’m sitting next to Bambaataa. It was amazing. I had only been a photographer for maybe two years at that point, but as soon as I started working at NME I didn’t find it very difficult to get work. I was very lucky in that sense. Often when you go abroad in those days working for rock magazines and papers, you’d maybe spend several days somewhere, but you might only have ten minutes to take photos, so you’ve gotta kill the time somehow. You can’t just sit in the hotel watching TV. That’s not my way. So I would go off wandering around. I would seek adventure, and take photos along the way. Between 1984 and 1996, I probably went eight or nine times. I would try and get someone to commission me, and if they didn’t, I would go anyway. The whole time I went to the festival I only ever saw two films. I always looked forward to the event, but I wouldn’t look forward to seeing films. It’s so hot and so great at Cannes. Why would you want to sit there watching films? It seems crazy to me.

I feel that I’m a bit of an opportunist photographer, though I don’t go around with my camera so much anymore. I used to carry it everywhere and photograph anything that was interesting to me, and it would almost always be people. It wouldn’t have to be subcultures. I would photograph anyone. In the 1980s I shot Ayrton Senna whilst he was practising for the Grand Prix. For the best part of 25 years I considered myself a rock photographer. I don’t do that anymore. People aren’t so interested in those photographs—they’re interested, now, in whoever they like. If they’re interested, it’s not because of my photographs, but because of the people who are in them.

I try to be nice. I don’t feel intimidated by people. Maybe they could intimidate me if they tried, but they don’t tend to try with me. I once got kicked in the balls by a skinhead, who then tried to steal my camera from me and we had a bit of a wrestling match. I saw the same bloke afterwards and he still let me take a photo of him. He was a nice-looking guy as well. A really handsome bloke, but he had a few issues. I’ve had a few terrible experiences with people. One was with Genesis P-Orridge—I got thrown out of his house. He said I couldn’t come round his house swearing at his friends. Which I did. He deserved it. His friend was in the background while I was taking pictures, talking about how terrible NME was. I kept quiet until I had finished the photographs, then I told him what I thought of him.

It was just completely crazy. It didn’t always reflect that well on male photographers, or, for that matter, men in general. But the awards did attract

a lot of attention, and it was almost exclusively male attention. If I stand next to a porn star in any situation, I become invisible. No one’s looking at me. That’s good for a photographer. You can take photographs and no one knows what you’re doing, because they’re so focused on the porn star.

It influenced my path to becoming a photographer. It’s not a film I really like that much, actually. But it came at just the right time, just as I was finding myself. It was the lifestyle of this bloke. I would have been 15 when it came out, and I wanted to be a painter rather than a photographer at that time, but I thought, this is what I want. I want to live in a big studio apartment. I want to drive around in a convertible Rolls-Royce and have beautiful young women knocking on my door.

I’m a big fan of Helmut Newton. I saw him shooting a model on Carlton Beach, right in front of the Carlton Hotel. Newton was well known for going to the Cannes Film Festival and shooting fashion pictures. I had been seeing them in the 1970s, long before I became a photographer myself.

I was watching him taking photographs and at one point he said, “You’re so close to the model, why don’t you get in the picture yourself?” So I did, and I swivelled around and took a photograph of him. I never saw the photo he took of me. It might have been a ploy. But he was friendly—he didn’t say it in a nasty way. I didn’t meet him after that, or else I would have asked: what happened to my photo?

As you can see he’s not that into it, but you do what you can. He wasn’t particularly friendly, but, then, I don’t expect people to necessarily be friendly. I do have to manage emotions to some extent. I can’t afford to walk into a room and piss someone off the moment I get in there. I suppose I’m a little cantankerous, but I’m certainly polite when I meet people. Some people just aren’t up for being photographed, especially film stars. Sometimes you’d just have one minute to shoot after the interview took place. And I quite liked that, because then you’d need to have a plan. You can’t just wait for them to turn up, have a cup of coffee and ask them how they’re feeling. You get straight into it. I don’t mark them down because they aren’t friendly to me. Who am I? Ten minutes after I walked out of that room, he would have forgotten about me forever. But I’ll always remember him. I’ll always remember that ten minutes. He’s made some great films, that’s the main thing. I don’t allow it to affect how I perceive their art. I’m not that into myself that it matters that they might be rude or unpleasant to me on one day of their life.

Spike Lee in his hotel room at the Cannes Film Festival, 1989. By Derek Ridgers.

It wasn’t a conversation. He was approaching the driveway of the Carlton Hotel. I had an Olympus Mju, a tiny camera that could fit into the palm of my hand. There was just enough space in the gap in the window for me to get my hand through it. As I took my camera back out, Clint smiled at me, because I think he appreciated a bit of initiative. I never would have got an FM2 through the window.

Clint Eastwood arriving at the Carlton Hotel during the Cannes Film Festival, 1994. By Derek Ridgers.

I shot him at the Trainspotting party. You can see from that photo that he doesn’t want to be shot either. He’s trying to ignore me. He’s got the thousand-yard stare. He doesn’t want to be spoken to. I really like Altman’s films, but I don’t think he was overly friendly.

Robert Altman at the Trainspotting party. Palm Beach Casino, the Cannes Film Festival, 1996. By Derek Ridgers.

He was making a film called Starlet. And there never was a John Hurt film called Starlet. If you see from my photograph, he’s wearing a crazy wig surrounded by young starlets. The film never got made, but there was a lot of talk about the film in the daily papers at Cannes. I read that they were going to have a big party in one of the villas overlooking the bay, and I knew it would be the kind of party I was going to have to gatecrash. Now, this is one thing you need to avoid if you’re planning to gatecrash a party: never be the first one to turn up. I got there and there was no one around. I knock on the door and they look at me, and I look at them, and I’m taken into this big room with a beautiful window overlooking the harbour. The only person in the room is John Hurt, and he’s on the sofa lying on his back, talking into his phone quite loudly. For about half an hour I was standing there on my own looking out of the window, drinking white wine, and Hurt completely ignored me. It was like I wasn’t there. He was on the phone, so he wasn’t doing anything wrong, and I wasn’t meant to be there in the first place, but it was embarrassing for that half an hour. Eventually people came, and they were very friendly. I met the actors who were going to be in the film. I met Carmine Caridi from The Godfather Part II. He was a well-known actor but never a star. Big Italian-American guy, very friendly bloke. I had a long conversation with him about his life and how he grew up with a lot of gangsters—all his friends became gangsters and he became an actor. So, eventually, I had a great time.

John Hurt at the Starlet photocall, the Cannes Film Festival, 1988. By Derek Ridgers.

I discovered that I photographed Bob when I was looking through my negatives, but I really have no recollection of taking the photographs or why I was doing it. At Cannes, you get used to running around, shooting whoever you can. I didn’t want to be told what to do. The time that I was being given to do those [assigned] photos was taking away from the time that I could have been photographing the circus.

Celebrate cinema and the summer with Derek Ridgers’ latest photobook, a partnership with our friends at IDEA that collects his most iconic images from his time at the Cannes Film Festival. Cannes celebrates 12 years of Ridgers’ adventures on the Croisette—a frivolous record of the film festival at its most unfiltered—but make no mistake, these are a far cry from your typical

studio-sponsored paparazzi portraits, with Ridgers not only capturing cinema’s most glamorous stars, but unflinchingly turning his lens onto the photographers that fawn over them. Our pick for the most stylish coffee-table book of the season, Cannes is available from IDEA and Dover Street Market.