The quietly influential and boldly innovative Japanese director discusses three decades of Love Letter, meeting Tarantino at Sundance, the making of All About Lily Chou-Chou, and how piracy made his debut feature a hit in South Korea.

During a visit to Propaganda Film Store in Seoul last month, I stumbled upon a surprisingly thorough collection of memorabilia for the Shunji Iwai film Love Letter (1995).

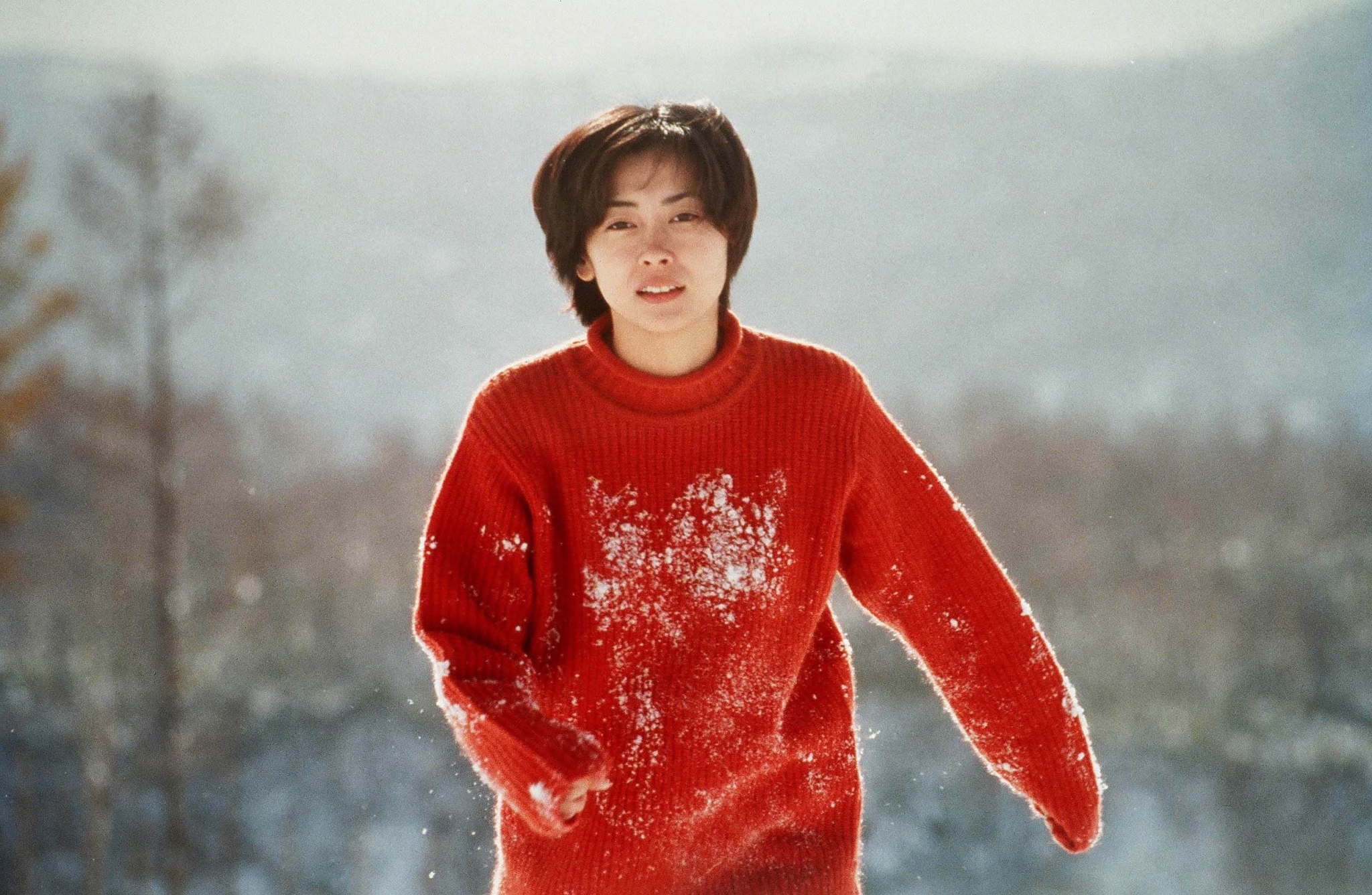

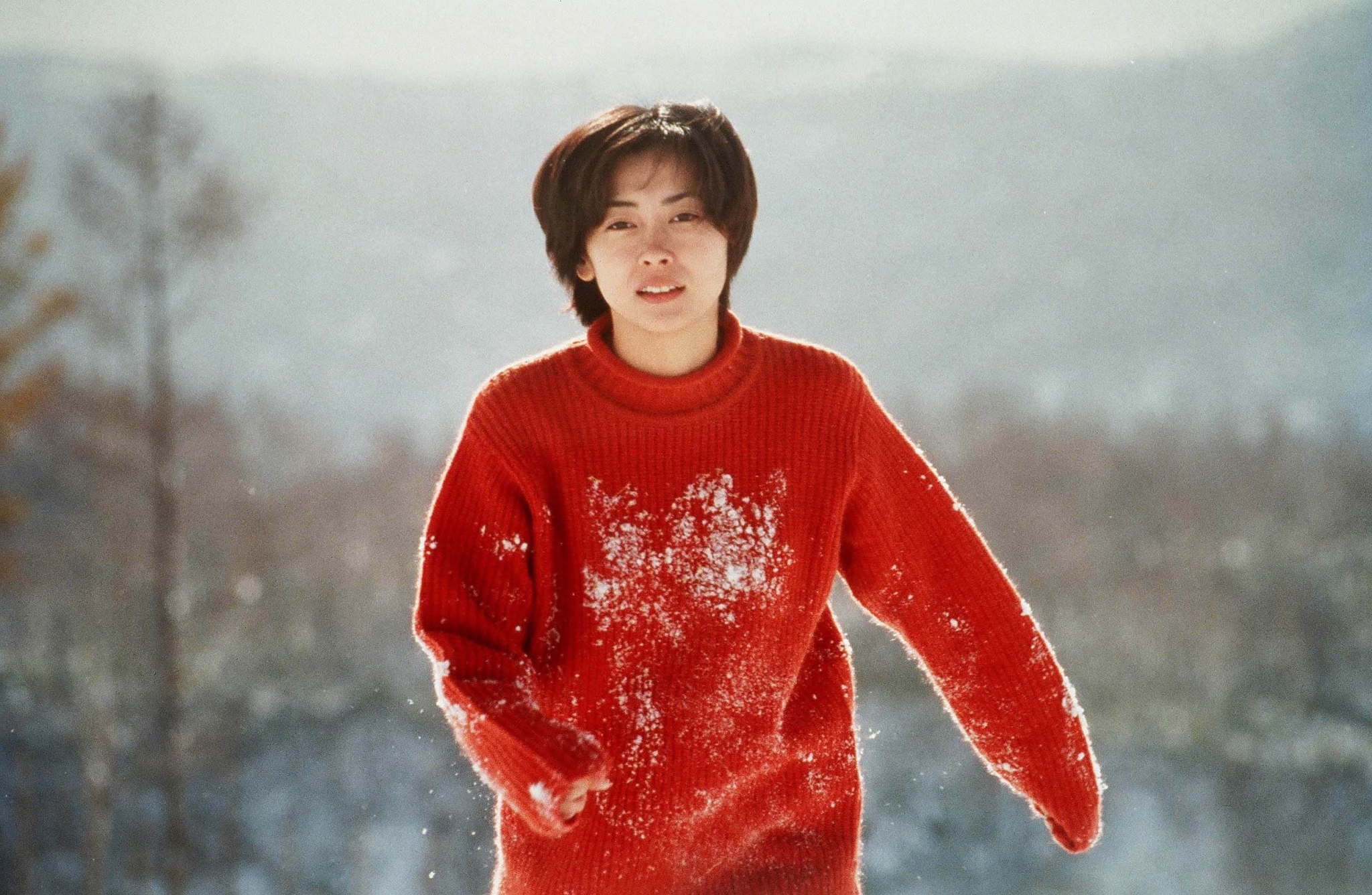

Rare posters and film miscellanea are dotted around every corner of the shop, an unassuming crack in the wall tucked away on a quiet street in Sinsa-dong. Heavily curated and only open on the last Saturday of every month, It’s the ultimate haven for a cinephile looking to get into the heart of film culture in South Korea. Still, the establishment’s dedication to Love Letter feels particularly thoughtful. Look to your left and you’ll see a VCR copy of the film sitting atop a stack of videos reaching about six feet high; to your right—slotted between an original press pack for Jim McBride’s Breathless (1983) and a vintage programme for an old Edward Yang retrospective in Singapore—you’ll find a copy of Korean film magazine Cine21 celebrating the Japanese film’s re-release in cinemas; leaning against the wall is a framed Love Letter poster, showing Miho Nakayama—the lead actress and beating heart of the film, who tragically died last December at 54—gazing longingly into the sky against a snow-white backdrop.

“It’s the movie of my life,” store owner JeeWoong Choi had said, excitedly sliding a Love Letter vinyl off a shelf to show me. “I’m a super big fan of Iwai Shunji.”

But Choi is far from the only one in South Korea with an affinity for Iwai’s debut feature, which has been celebrating the 30 year anniversary of its release with a series of packed-out screenings across Seoul. Upon release in 1995, the film became an instant hit there. “I don’t really know why,” Iwai admits, calling me from his office in Tokyo. “I think it was partly to do with the time around 1995. It was the beginning of a new era in Korea. This change of direction towards democracy and capitalism, and this new trend of being officially able to import Japanese films. 30 years on, people are still watching Love Letter, including young people. I’m very happy about that, but I have no idea what’s going on.”

Love Letter follows Hiroko Watanabe and Itsuki Fujii (both played with an innate duality by Nakayama)—the former, a reserved woman from Kobe grieving the tragic death of her fiancée, and the latter, a bubbly librarian living in snowy Hokkaido—who strike up a letter correspondence after Hiroko realises that Itsuki shares the same name as her dead fiancée, and also went to high school with him. Their back and forth soon prompts Itsuki to reflect on her brushes with the male Itsuki during their youth. “Diaries and letters were an important tool back then,” Iwai says. “I had been thinking for a few years of writing a strange story that involved letters.”

Iwai is the first to admit that the film carries some of the DNA of Krzysztof Kieślowsk’s The Double Life of Veronique (1991), as well as more obscure works like 84 Charing Cross Rd (1987) and the Jack Finney short story The Love Letter (1959). Nevertheless, with Love Letter, the first-time filmmaker, alongside cinematographer and longtime collaborator Noboru Shinoda, who imbues each frame of the film with a dreamlike temporality, crafted something that to this day feels astoundingly singular in form and profoundly moving—a tender meditation on the nature of memory that shoots straight for the heartstrings.

In the 30 years since releasing the film, setting up production company Rockwell Eyes, and releasing a slew of beloved films such as April Story (1998), A Bride for Rip Van Winkle (2016), Hana & Alice (2004), and All About Lily Chou-Chou (2001), Iwai has remained a boldly innovative and quietly influential filmmaker. He was once championed by Quentin Tarantino, who referred to Iwai’s Swallowtail Butterfly (1996) as “Japan’s Pulp Fiction” (1994), and even went as far as to use one of Iwai’s original songs (’Kaifuku Suru Kizu‘, performed by fictional singer Lily Chou-Chou in All About Lily Chou-Chou) in his 2003 feature Kill Bill. “[He’s a] really terrific director.” Tarantino had said at the time. “He has my career in Japan…the All About Lily Chou-Chou soundtrack is really cool to make out to.”

“I met Tarantino at the Sundance Film Festival.” Iwai remembers. “Initially, he was like ‘who are you?’ [laughs] so I told him about my movies and that he used my music in his films. Then he gave me a hug. I’m honored that he appreciates my work.” In 2021, the All About Lily Chou-Chou soundtrack received another tribute, this time by filmmaker Kogonada, who recruited Mitski to perform a cover of Glide for his film After Yang. The reference is slight and subtle, but for those in the know, it’s a deeply affectionate nod to the groundbreaking film, which saw Iwai unconventionally embrace digital filmmaking and explore the millennial generation’s early relationship with the internet. In conversation with Letterboxd, Kogonada described his connection to the film, saying, “the mood of that film haunted me when I saw it…I’ve never gotten over it. I think it resides in me.”

Yet, after three decades, Iwai is still allowing himself to be humbled by the process, and, reflecting on his career, seems more relieved than anything, not only that audiences are still seeking out his work, but that after all this time there’s still plenty of fire left in his belly. “For me, making films is an unknown adventure,” he says. “I’m just glad I managed to make it this far without having a mental breakdown. I’ve made it.”

Below, we sat down with Iwai to discuss three decades of Love Letter, his views on AI, the making of All About Lily Chou-Chou, and how piracy made his debut feature a hit in South Korea.

Shunji Iwai and longtime collaborator Noboru Shinoda on the set of All About Lily Chou-Chou (2001). ©2001 LILY CHOU-CHOU PARTNERS.

Luke Georgiades: Do you go to the movies very often?

Shunji Iwai: For the last 30 years, I’ve hardly had the time to go to the cinema. I went to the cinema a lot up to my 20s, but since then I tend to make films rather than watch them. I love making them. The things I do watch are things I can use in my work: the news, documentaries, reportage, comics. And the films I do watch tend to be older films. The classics.

LG: Do you feel much nostalgia towards Love Letter, as your first feature?

SI: I was very young back then. I think the younger we are, the more a sense of nostalgia we have. The most nostalgic I ever felt was in Junior High School. I was nostalgic for primary school. Now, 30 years on, I don’t look back on Love Letter with that sense of nostalgia. I’m more likely to recall things that happened recently in that way. Maybe it’s a sign I’m losing my sensitivity with age.

LG: Miho Nakayama’s twin performance is the heart of the film. What initially struck you about her as a person that you knew would be perfect as Hiroko and itsuke?

SI: Within Miho Nakayama, there were two faces—her public and private selves. The two main female characters in the story each had aspects of her personality, but I feel that inner duality existed within her as well. She had previously played a lot of comical roles, so I knew she would be perfect for the spirited Itsuki. But for Hiroko, who has lost her partner, who is feeling depressed…I didn’t know how she would cope with that. But when I met her, I discovered that she wasn’t, as her screen persona would suggest, always an energetic character, but a very private, quiet girl. I knew, instinctively then, that she would be able to play both roles. She had this dichotomy to her personality and this intense conflict between them. I don’t think I know anyone else who struggled so hard to protect themselves from being too famous. I think she was someone very sensitive. Her passing is truly heartbreaking.

“[Miho Nakayama] had this dichotomy to her personality and this intense conflict between them. I don’t think I know anyone else who struggled so hard to protect themselves from being too famous. I think she was someone very sensitive. Her passing is truly heartbreaking.”

Shunji Iwai

LG: How has your process evolved since making Love Letter? Do you feel as if you’re still finding yourself as a filmmaker?

SI: I didn’t expect Love Letter to be my film debut. I was intending it to be a TV drama. I thought Swallowtail Butterfly would be my first. The TV plans fell through, and a producer suggested we turn it into a film. I was in a tricky position, suddenly discovering that my first film would now be this tiny little story about a letter. Initially, I was planning for it to be black and white. I was going to replicate Yasujiro Ozu’s world, in terms of the shots and the angles. There was only one protagonist. The second lady who lost her fiance didn’t appear at all—there was just one woman who had been matchmade in a very Japanese way, and was going to go off and be a bride. During the few months before her wedding, she received a letter from someone she doesn’t know, and it triggers memories from her school days. It was very Ozu-esque. When I found out it was going to be a film, I had to quickly rewrite it. I’ve never been so glad, then, to have been such a curious film student. The roots of my storytelling are back then. I would ask myself: what is cinema? How do you really tell a story? And nobody would get in my way of examining those questions. Since I made my professional debut, I’ve been trying to improve on that. That initial creative impulse remains vivid, and even now, I continue to chase after my younger self’s vision. Even as I made Love Letter, I was trying to catch up with the 20 year-old me. Even though I wasn’t as good at it as I am now, I had never been more naive and passionate about making films. I was curious. As long as I can keep hold of that and not forget what I was like back then, then I can keep working. For me, making films is an unknown adventure. I’m just glad I’ve managed to make it this far without having a mental breakdown. I’ve made it.

LG: There’s a debate going on online right now about the ethics of piracy. I wonder how you feel about that, as a filmmaker whose movies are hard to access in some countries?

SI: When Love Letter came out and it was such a hit in Korea, most people saw a pirated version. April Story came out before Love Letter in Korea, and I premiered it at the Busan Film Festival. During that premiere, I asked the audience if they had seen any of my previous movies, and most of them said yes, but the film they had seen was Love Letter . They had seen it before it had actually been released. But, as a result, everyone in Korea has seen Love Letter [laughs] and I am where I am now. Maybe that’s not ideal, but for me, personally, I don’t mind at all. The fact that someone dedicates part of their life to my film is a miracle to me. I think it’s becoming easier to consume art, and I believe that once the platforms are in place more people will be able to find my films. Until then, if there are films you haven’t seen of mine and you would like to organise a small screening, let me know, and I’ll come over and we can watch it together [laughs].

“Even as I made Love Letter, I was trying to catch up with the 20 year-old me. Even though I wasn’t as good at it as I am now, I had never been more naive and passionate about making films. I was curious. As long as I can keep hold of that and not forget what I was like back then, then I can keep working. For me, making films is an unknown adventure. I’m just glad I’ve managed to make it this far without having a mental breakdown. I’ve made it.”

Shunji Iwai

LG: All About Lily Chou-Chou is also celebrating a milestone of 25 years. The film captures this intense feeling of isolation of a generation. How did you have such a finger on the pulse of what that generation was feeling at the time?

SI: There are things you remember when you were a child, and things you don’t. I remember witnessing bullying at school. In Japan, especially, if you were part of a sports club at school it was like going into battle. It was like being a soldier. At high school I decided I hated that and I joined an art club. When I went to University, I joined the film club. I chose a softer direction. But when I started working in the film world as a professional, I discovered I was going back into battle. It was hard. There was some power harassment. It was horrible. You don’t forget that. On the other hand, they do make for good inspiration for stories. The worse your experience has been, the bluer the sky looks. There’s a lot of that in All About Lily Chou-Chou. There are a lot of blue skies, or skies that seem bluer.

LG: I remember watching it for the first time and feeling betrayed by just how far Hoshino descends into cruelty. Why is it important to you on occasion to take your films to those extreme places of darkness?

SI: I was just trying to be faithful to the subject. It’s a film about bullying, and I talked to a lot of people who had both been bullied and bullied someone themselves. It’s just awful. There’s no way out. There’s just pain and hatred. In the film I tried to offer some faint hope through the character of Lily, this commonality that the bully and the victim share. But in the end, even that isn’t God. It’s not salvation. It’s just a fantasy. That’s what it’s like for people experiencing it in real life. I couldn’t betray those people by giving the film a happy ending. I couldn’t leave them behind. I meet people even now who watched the film, aged 14, and say that it saved them. I wonder why, but I think it must be because they just saw someone like them. They’re not given a happy ending, but they just…survive. They make it through. It was hard for me to make that film.

LG: All About Lily Chou-Chou was one of the first films I saw that actively displayed the way young people use the internet to find community. How has your feeling about the internet evolved since making the film?

SI: I’ve always thought the internet was a strange world. When I was making the film I would go to bulletin boards and read threads about bullying, and ask questions. But when some people found out who I was I would get comments attacking me on my own website. People who I was chatting with happily would suddenly turn on me. Before the internet came along we tended to, at least in cities, ignore each other. The internet was a counterpoint to that. Suddenly you could talk to people who were complete strangers. You wouldn’t need to even say hello, and you could say things to deliberately hurt them. We’ve reverted to our most primal nature. When we find ourselves in different environments our identities turn out to be fluid. If we’re given a box labelled “war”, we will slot ourselves into that, and drop a bomb on a stranger via a drone. If we’re given a vessel called “patriarch” and a man feels like the king of his household, he might be violent towards his wife and his children. We need to think more about what we would like to be, rather than going with the flow and changing shape and turning into monsters. I’m no exception to this. I need to think about this too. It’s not a product of the time, it’s always been human nature.

“The worse your experience has been, the bluer the sky looks. There’s a lot of that in All About Lily Chou-Chou. There are a lot of blue skies, or skies that seem bluer.”

Shunji Iwai

LG: The character of Lily Chou-Chou was inspired by Faye Wong—what did you see in her music that felt so appealing to the themes that you wanted to explore in the film?

SI: I saw her live in Hong Kong in a big stadium in 1998. I remember projecting the protagonist of Lily Chou-Chou and forming the story as I was listening to her sing, and noticing the distance between me in the audience and her on stage. The contrast between a media-dwelling diva and an individual living in the countryside was key to what I wanted to express. I felt that she had this natural, transparent sound. I later used her song ‘Shanghai Guniang’ in Swallowtail Butterfly.

LG: You started to shoot on digital from All About Lily Chou-Chou. Do you ever see yourself moving back into using film?

SI: I no longer think about going back. In my student days, I shot on 8mm, and my room was filled with film reels. Now, everything fits on an SSD. Film labs today lack the proper infrastructure, and in the past, huge amounts of processing chemicals were dumped into rivers and oceans. Considering environmental concerns, I see no reason to return to film.

LG: You’ve always allowed yourself to evolve and experiment with new technology and formats. How are you feeling about the looming threat, if you’d like, of AI in the arts?

SI: I think it’s hard for human creativity to compete with AI. There’s a sense of “what’s left for us to do?” In the end, I think, what’s left for us is the desire to make something. I don’t make films because I love cinema. I make films because I want to make films. Audiences still value that. Those are the two sides of the coin. As long as we want to make things, and as long as the audience respects the effort that goes into it, then we can survive. But if the audience decides that they’re fine with something made by AI, then there will be nothing left for us to do. I can foresee a time where there’s demand for My Neighbour Totoro Part 2. You punch it into AI, and it comes up with four different sequels for children to pick and watch. It’s hard to avoid that eventuality. But I believe people will continue to make films for a while yet. As I get older, maybe my motivation will decline, but until then I want to try and be inspired by the motivation of my youth and carry on too.