Brutalism, often dismissed as harsh and masculine, hides a rich history shaped by visionary women. From Lina Bo Bardi’s bold designs in Brazil to Svetlana Kana Radević’s monumental works in Montenegro, Amelia Stevens uncovers how female architects redefined the movement—combining raw materials with innovative beauty to leave an indelible legacy.

Originating from the Latin brutus (feminine bruta)—whose multiple meanings include dull, stupid, and irrational, or heavy, inert, and unwieldy—connected across a family of interwoven European languages, the brutalist architecture movement has suffered from its association with the savage brute.

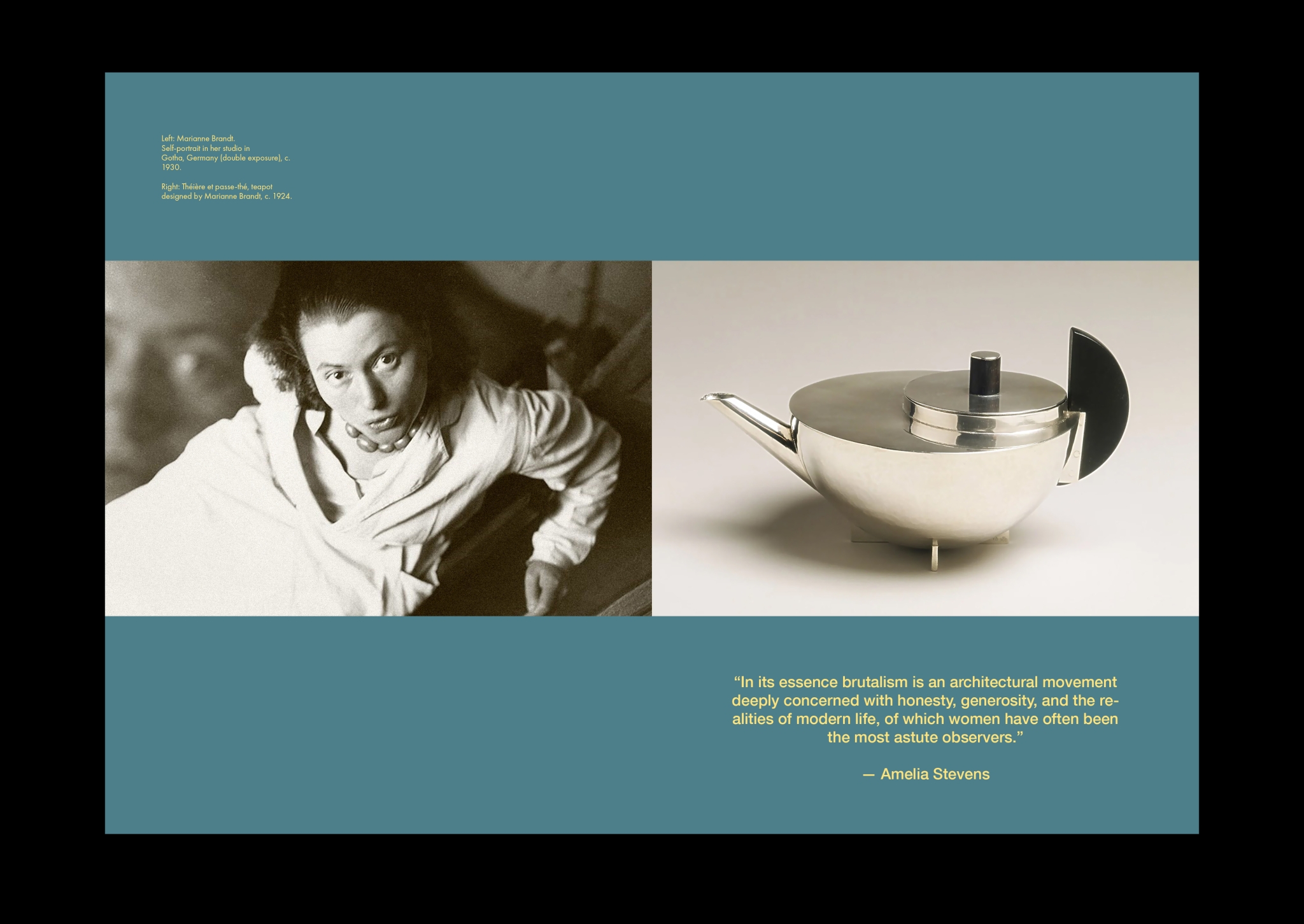

From instigators of wars to petty thieves and vandals, countless men throughout history have earned their characterisation as brutes, yet in its essence brutalism is an architectural movement deeply concerned with honesty, generosity, and the realities of modern life, of which women have often been the most astute observers.

Despite a pervasive system of exclusion, subordination, and misattributed authorship intended to keep them anonymous, throughout the 20th and 21st centuries a handful of exemplary female architects, including Lina Bo Bardi, Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak, Renée Gailhoustet, and Svetlana Kana Radević, received recognition for their uniquely beautiful, innovative, and sensitive brutalist works. Although latterly eclipsed by the output of their male counterparts, too “heavy, inert, or unwieldy” to be easily demolished—constructed in materials from concrete to Carrara marble—brutalism’s reverence for the scale, quality, and permanence of materials has, in turn, served as an impenetrable defence guarding against the loss and erasure of their works.

In its essence brutalism is an architectural movement deeply concerned with honesty, generosity, and the realities of modern life, of which women have often been the most astute observers

Amelia Stevens

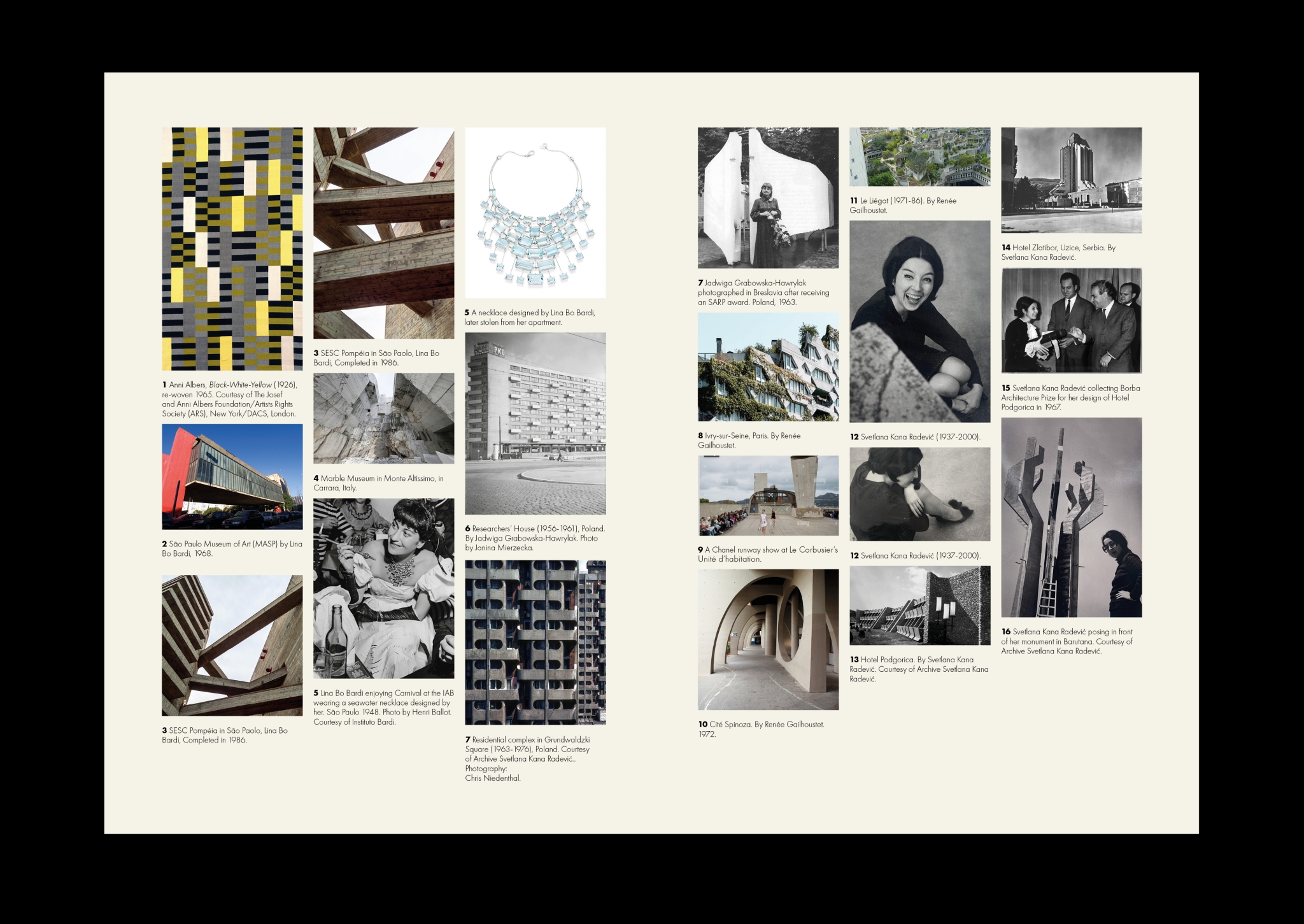

Brutalism was preceded by the Modern Movement. At the Bauhaus founded in Weimar, Germany—the most progressive art school of the modern era—female students were encouraged to pursue ephemeral mediums. With the exception of Marianne Brandt (1893-1983), who became the first woman to be admitted into the metal workshop and eventually took over as department director, while other exemplary students such as Anni Albers (1899-1994) and Otti Berger (1898-1944) produced beautiful, even highly technical, abstract textiles combining geometric, “hard-edge”, and linear forms, the medium’s inherent temporality was at odds with its historical conservation and many works, including Albers’ Black-White-Yellow (1926) woven in cotton and silk, were lost until rewoven decades later.

With the closure of the Bauhaus under the Nazi regime in 1933, and the outbreak of war imminent, many male architects escaped Europe for exile in the United States, where, as demonstrated by the character of László Tóth (played by Adrien Brody) in Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist (2024), they took up prestigious teaching positions and commissions orchestrated by rich donors and philanthropists. This was not all too dissimilar from the mysterious and wealthy industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) who seemingly offers Tóth the American Dream on a silver platter when he invites him to design the most ambitious project of his career, a grand modernist monument that will help shape the landscape of modern America. Their female counterparts more often stayed behind to take care of family or later returned to Europe, where the destruction of their archives and the absence of employment prospects further compounded their erasure.

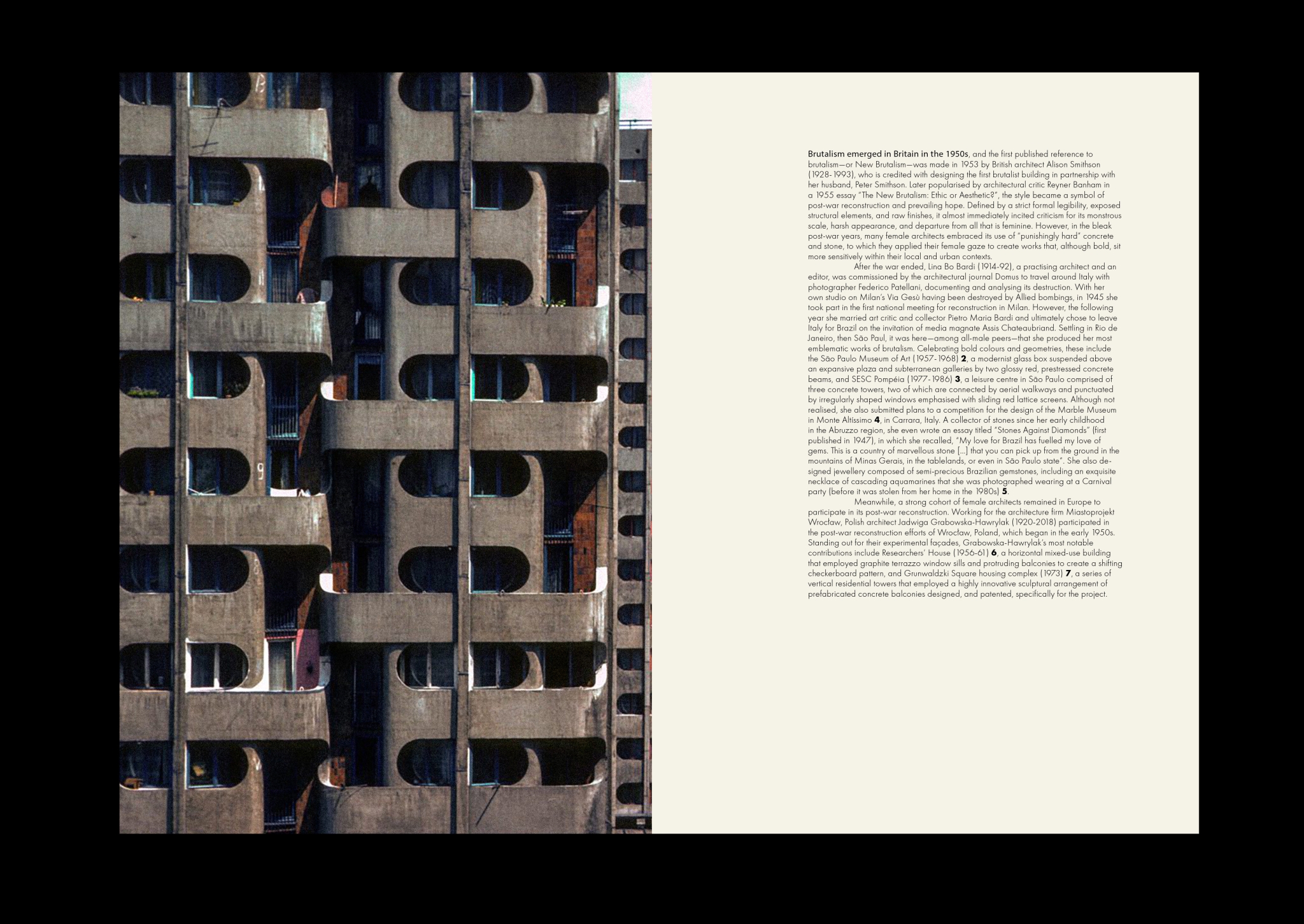

Brutalism emerged in Britain in the 1950s, and the first published reference to brutalism—or New Brutalism—was made in 1953 by British architect Alison Smithson (1928-1993), who is credited with designing the first brutalist building in partnership with her husband, Peter Smithson. Later popularised by architectural critic Reyner Banham in a 1955 essay “The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic?”, the style became a symbol of post-war reconstruction and prevailing hope. Defined by a strict formal legibility, exposed structural elements, and raw finishes, it almost immediately incited criticism for its monstrous scale, harsh appearance, and departure from all that is feminine. However, in the bleak post-war years, many female architects embraced its use of “punishingly hard” concrete and stone, to which they applied their female gaze to create works that, although bold, sit more sensitively within their local and urban contexts.

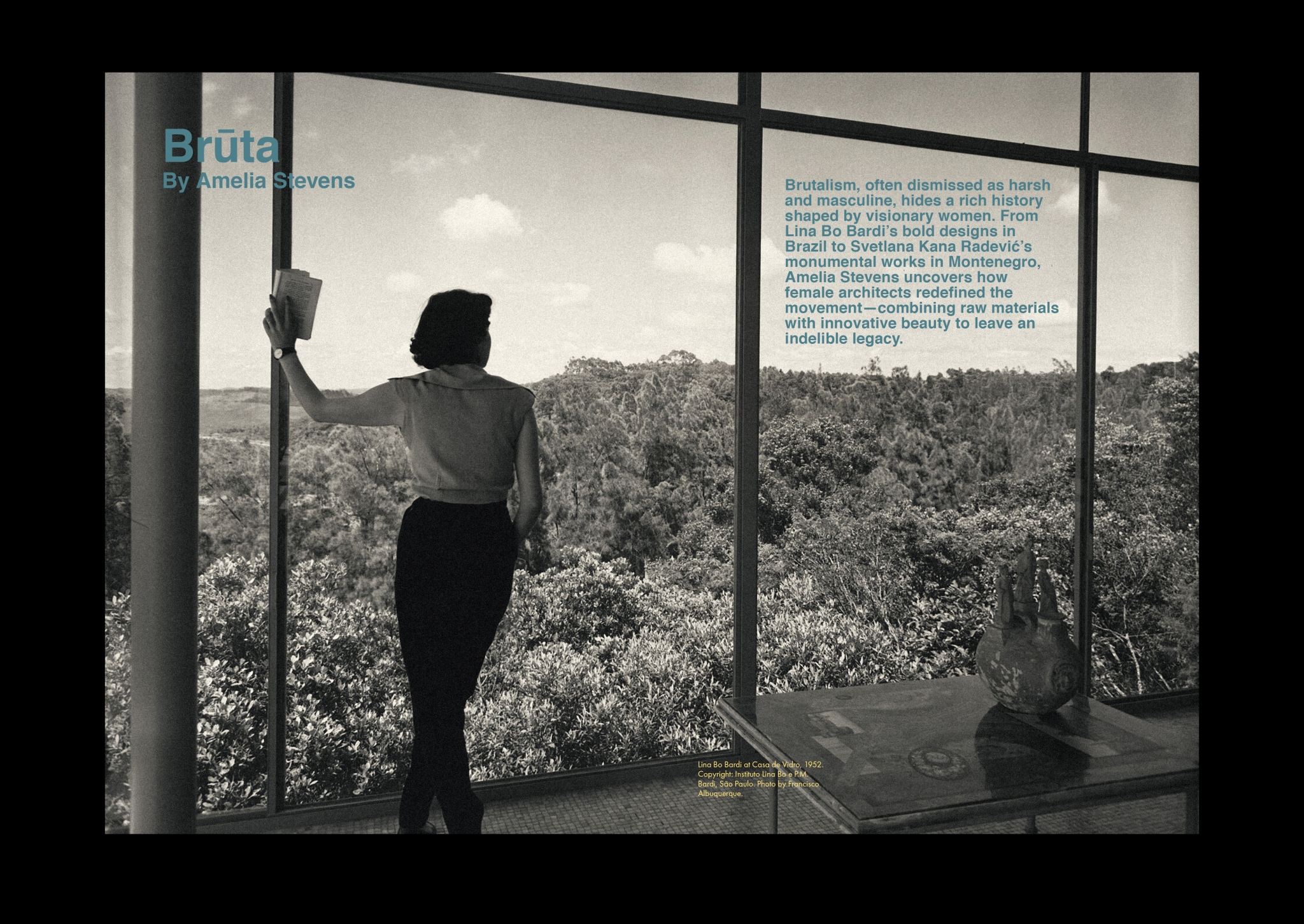

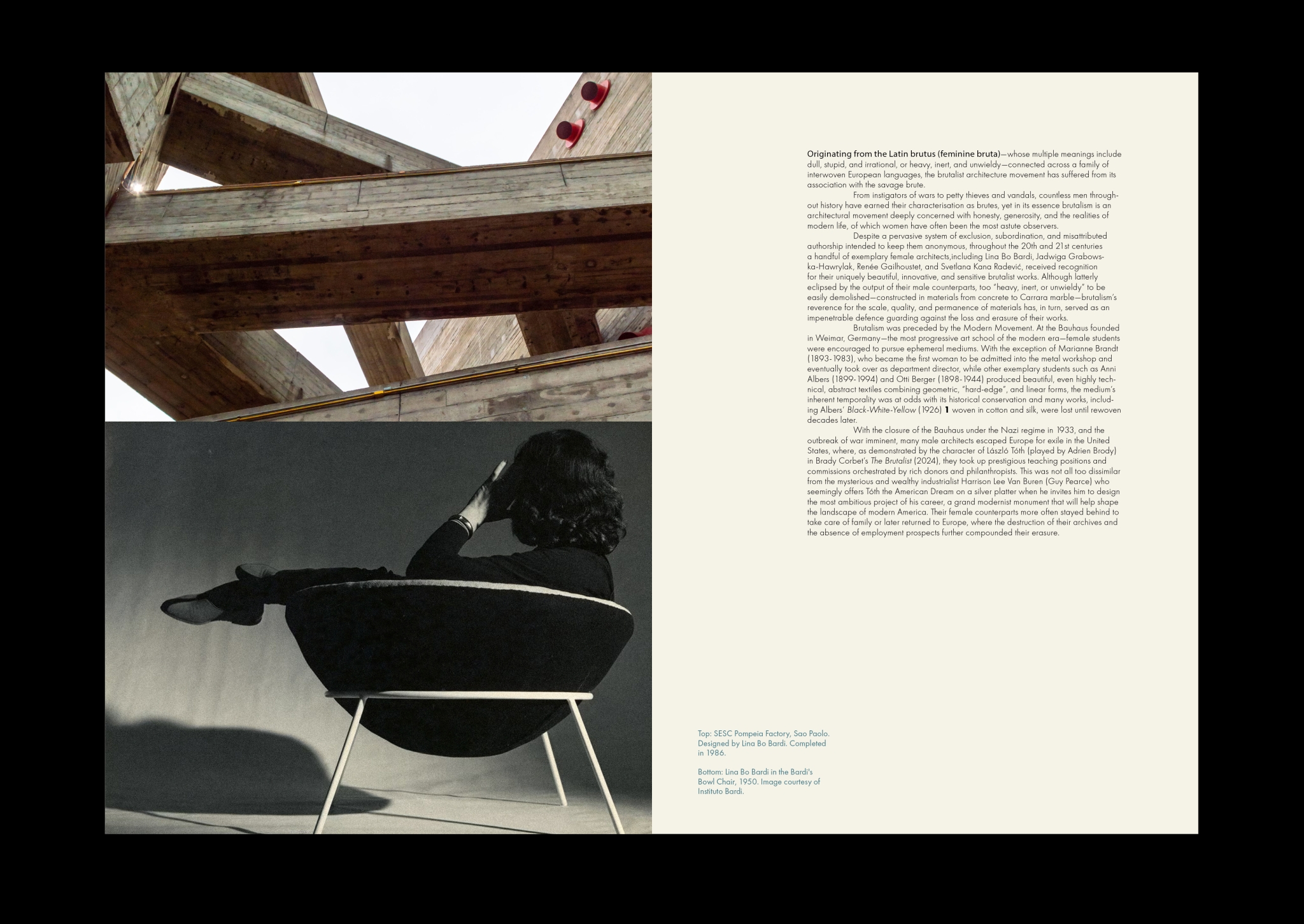

After the war ended, Lina Bo Bardi (1914-92), a practising architect and an editor, was commissioned by the architectural journal Domus to travel around Italy with photographer Federico Patellani, documenting and analysing its destruction. With her own studio on Milan’s Via Gesù having been destroyed by Allied bombings, in 1945 she took part in the first national meeting for reconstruction in Milan. However, the following year she married art critic and collector Pietro Maria Bardi and ultimately chose to leave Italy for Brazil on the invitation of media magnate Assis Chateaubriand. Settling in Rio de Janeiro, then São Paul, it was here—among all-male peers—that she produced her most emblematic works of brutalism. Celebrating bold colours and geometries, these include the São Paulo Museum of Art (1957-1968), a modernist glass box suspended above an expansive plaza and subterranean galleries by two glossy red, prestressed concrete beams, and SESC Pompéia (1977-1986), a leisure centre in São Paulo comprised of three concrete towers, two of which are connected by aerial walkways and punctuated by irregularly shaped windows emphasised with sliding red lattice screens. Although not realised, she also submitted plans to a competition for the design of the Marble Museum in Monte Altíssimo, in Carrara, Italy. A collector of stones since her early childhood in the Abruzzo region, she even wrote an essay titled “Stones Against Diamonds” (first published in 1947), in which she recalled, “My love for Brazil has fuelled my love of gems. This is a country of marvellous stone […] that you can pick up from the ground in the mountains of Minas Gerais, in the tablelands, or even in São Paulo state”.She also designed jewellery composed of semi-precious Brazilian gemstones, including an exquisite necklace of cascading aquamarines that she was photographed wearing at a Carnival party (before it was stolen from her home in the 1980s).

Meanwhile, a strong cohort of female architects remained in Europe to participate in its post-war reconstruction. Working for the architecture firm Miastoprojekt Wrocław, Polish architect Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak (1920-2018) participated in the post-war reconstruction efforts of Wrocław, Poland, which began in the early 1950s. Standing out for their experimental façades, Grabowska-Hawrylak’s most notable contributions include Researchers’ House (1956-61), a horizontal mixed-use building that employed graphite terrazzo window sills and protruding balconies to create a shifting checkerboard pattern, and Grunwaldzki Square housing complex (1973), a series of vertical residential towers that employed a highly innovative sculptural arrangement of prefabricated concrete balconies designed, and patented, specifically for the project. Known endearingly by residents as “The Principality of Monaco” or “Manhattan”, although it was originally intended to be finished in sleek white concrete and covered with plants, cast in rough concrete—and only later painted white in her honour—Grunwaldzki Square became an accidental icon of the brutalist movement, for which Grabowska-Hawrylak became the first female architect to be awarded the prestigious Honorary Award from the Association of Polish Architects in 1974.

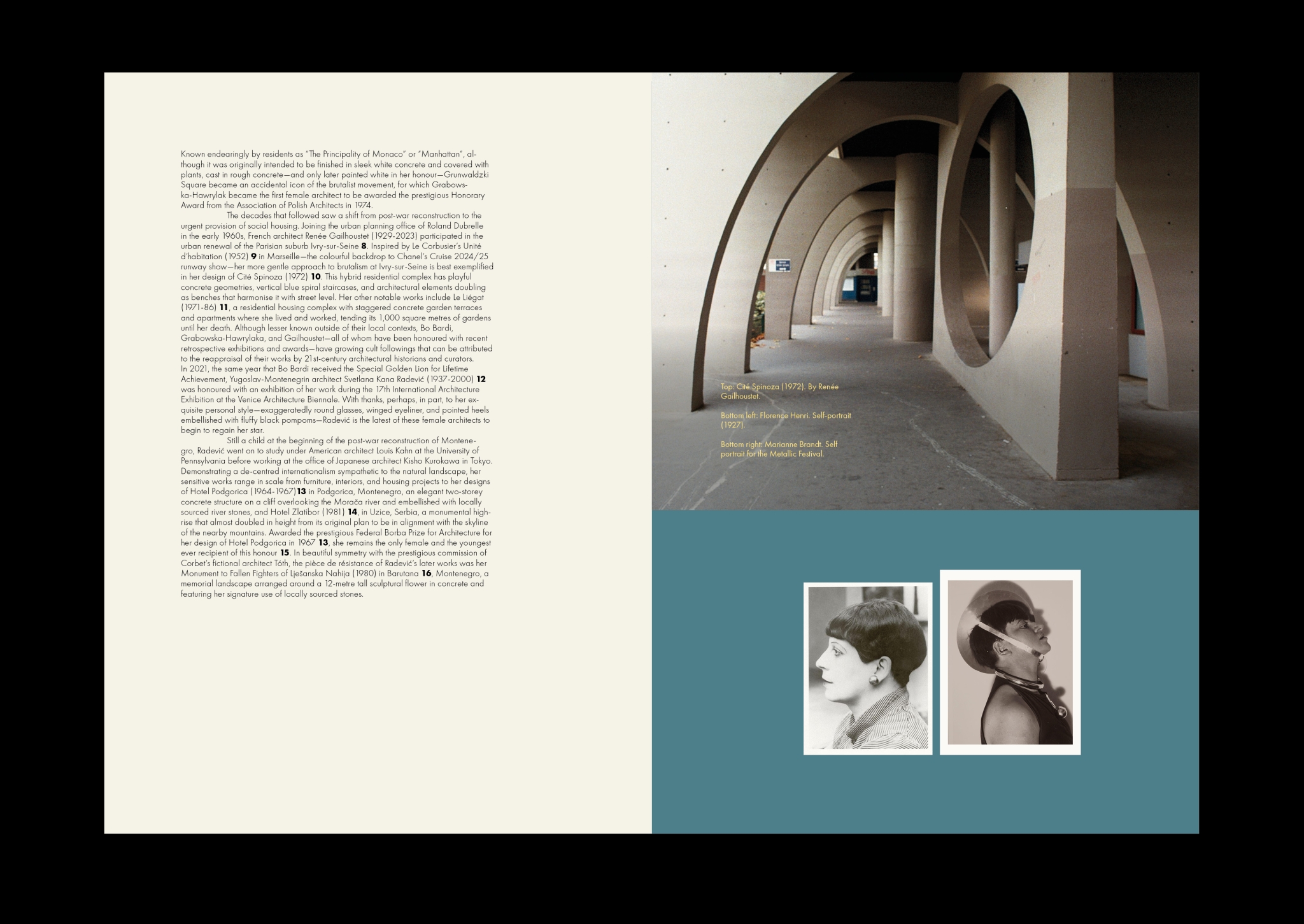

The decades that followed saw a shift from post-war reconstruction to the urgent provision of social housing. Joining the urban planning office of Roland Dubrelle in the early 1960s, French architect Renée Gailhoustet (1929-2023) participated in the urban renewal of the Parisian suburb Ivry-sur-Seine. Inspired by Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation (1952) in Marseille—the colourful backdrop to Chanel’s Cruise 2024/25 runway show—her more gentle approach to brutalism at Ivry-sur-Seine is best exemplified in her design of Cité Spinoza (1972). This hybrid residential complex has playful concrete geometries, vertical blue spiral staircases, and architectural elements doubling as benches that harmonise it with street level. Her other notable works include Le Liégat (1971-86), a residential housing complex with staggered concrete garden terraces and apartments where she lived and worked, tending its 1,000 square metres of gardens until her death.

“Their female counterparts more often went unrecognised and many either stayed behind to take care of family responsibilities or later returned to Europe, where the destruction of their archives and the absence of employment prospects further compounded their erasure.”

“Their female counterparts more often went unrecognised and many either stayed behind to take care of family responsibilities or later returned to Europe, where the destruction of their archives and the absence of employment prospects further compounded their erasure.”

Although lesser known outside of their local contexts, Bo Bardi, Grabowska-Hawrylaka, and Gailhoustet—all of whom have been honoured with recent retrospective exhibitions and awards—have growing cult followings that can be attributed to the reappraisal of their works by 21st-century architectural historians and curators. In 2021, the same year that Bo Bardi received the Special Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, Yugoslav-Montenegrin architect Svetlana Kana Radević (1937-2000) was honoured with an exhibition of her work during the 17th International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Architecture Biennale. With thanks, perhaps, in part, to her exquisite personal style—exaggeratedly round glasses, winged eyeliner, and pointed heels embellished with fluffy black pompoms—Radević is the latest of these female architects to begin to regain her star.

Still a child at the beginning of the post-war reconstruction of Montenegro, Radević went on to study under American architect Louis Kahn at the University of Pennsylvania before working at the office of Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa in Tokyo. Demonstrating a de-centred internationalism sympathetic to the natural landscape, her sensitive works range in scale from furniture, interiors, and housing projects to her designs of Hotel Podgorica (1964-1967) in Podgorica, Montenegro, an elegant two-storey concrete structure on a cliff overlooking the Morača river and embellished with locally sourced river stones, and Hotel Zlatibor (1981), in Uzice, Serbia, a monumental high-rise that almost doubled in height from its original plan to be in alignment with the skyline of the nearby mountains. Awarded the prestigious Federal Borba Prize for Architecture for her design of Hotel Podgorica in 1967, she remains the only female and the youngest ever recipient of this honour. In beautiful symmetry with the prestigious commission of Corbet’s fictional architect Tóth, the pièce de résistance of Radević’s later works was her Monument to Fallen Fighters of Lješanska Nahija (1980) in Barutana, Montenegro, a memorial landscape arranged around a 12-metre tall sculptural flower in concrete and featuring her signature use of locally sourced stones.