In her first column for A Rabbit’s Foot, Haaniyah Angus analyses the meme-driven discourse around sexual politics that have stemmed from the release of Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu and Halina Reijn’s Babygirl.

Whether you know the phrase or not, you will have witnessed something ‘breaching containment’ online. Maybe it’s your favourite niche musician getting traction or a meme going viral. It goes beyond its intended audience, and suddenly, what was once meant to exist in a small but beloved context breaks beyond its walls. Breaching containment has neither inherently good nor bad characteristics. However, for 2024’s Nosferatu and Babygirl—two wildly different films—breaching containment has led to conversations regarding their portrayals of sexual repression and desire at a time when accounts of intimacy seem to be at a significant point of contention.

Nosferatu is, at its heart, a classic example of a monster movie—a genre of film that utilises the monster as a pathway to examine our cultural and moral compulsions around the fear of the other, repression, sexuality and isolation. Director Robert Eggers is far from unfamiliar with utilising horror in this way, as his sophomore film, The Lighthouse, was an obvious examination of masculinity, queerness and loneliness told through nineteenth-century lighthouse keepers stranded at their post in New England.

In Eggers’ interpretation on Nosferatu, he takes inspiration from the 1922 film of the same name by swapping the location for Germany instead of London—where Bram Stoker’s 1897 Dracula (the vampire text upon which Nosferatu is based) takes place. Thomas (Nicholas Hoult) and Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp) live in a repressed society with clearly defined gender roles for men and women. In Thomas’s case, he feels he isn’t a good enough husband for his wife due to their financial standing. He travels to the castle of Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) under the false pretense of a job promotion. In his absence, Ellen finds herself returning to the Orlok-induced sleepwalking that has terrorised her since her youth. Her somnambulism places her at odds with wider society, where she’s seen as a hysterical woman who must be tamed for something she cannot control. This is emphasised by the medical treatment she receives from Dr. Wilhelm Sievers (Ralph Ineson). She is also tied to her bed and placed in a corset to “calm her womb and provide circulation.”

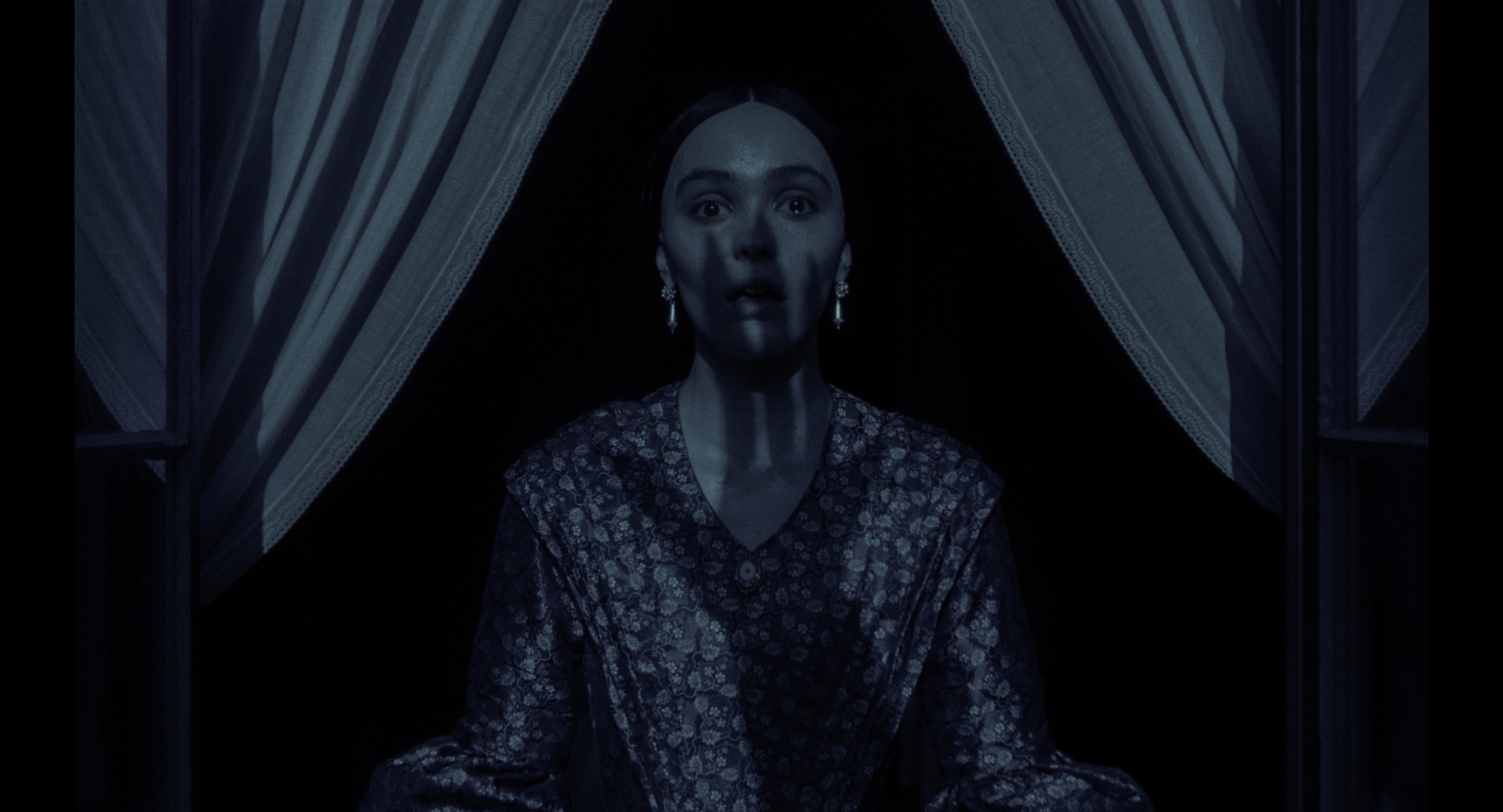

Lily Rose-Depp as Ellen in Nosferatu (2024).

Unsurprisingly, Nosferatu seems to be striking a chord with audiences and has spurred a social media frenzy with a myriad of tweets, memes, and videos of people attempting Skarsgård’s distinctive Transylvanian accent, but also a surprising amount of discourse interpreting the film both in a literal sense and as fantasy. Eggers’ depiction of the tale, whilst set in the 19th century, is fraught with modern readings regarding sexuality, consent, abuse and womanhood.

The internet we reside in today is not only post #MeToo, but has rapidly swung back into cultural conservatism with the re-emergence of Trump, Trad Wives and the ever-present knowledge that abusers seem to be avoiding justice. This is the same internet that witnessed Brock Turner’s lax sentencing, the inauguration of Brett Kavanaugh into the US Supreme Court and the horrific Depp v Heard case, all of which were pivotal cultural moments showing how sexual violence isn’t just allowed but in some cases is celebrated. For PhD student and Monster theorist Sanjana Basker, “More than ever, the slipperiness and the discomfort of the monster are a subject of public discourse,” she tells me. “Monsters have infiltrated so many aspects of our society, the wake of #MeToo where we found these non-fictional monsters in media, culture and life.”

Nicole Kidman and Harris Dickinson in Babygirl (2024).

It should be noted that unlike the movie monsters of the past in Universal’s canon, such as Frankenstein, the Creature of the Black Lagoon and The Wolf Man, all of whom garnered sympathy due to their portrayal as the persecuted other, Orlok in Nosferatu is very clearly meant to be a contentious character that repulses and yet intrigues us without nearly as much sympathy. There’s an apparently seductive nature that’s presented in Orlok, where he hypnotises, possesses and consumes his victims. As espoused by certain TikTok creators, for many, Nosferatu is a clear allegory for CSA (child sexual abuse). This interpretation isn’t without grounding. Ellen beckons Orlok as a young girl, and he psychically tortures her for more than a decade until their fateful meeting. That feeling of being drawn towards him despite what we know about his relationship with Ellen is meant to make us uncomfortable, and according to Hannah Raine, one-half of the podcast Rehash, that discomfort may be the issue. “I don’t even think it’s possible to explore those themes in art and not have someone feel uncomfortable with it,” she notes. “I also think that people conflate their discomfort with moral indiscretion, which, with art, makes it hard to know what’s an emotional reaction and what’s not.”

Nosferatu isn’t the only film of the season forcing viewers into a moral quandary, there’s an equal level of discomfort conflated with morality surrounding Halina Reijn’s erotic thriller Babygirl. The film has a simple premise: what would happen if a high-powered female CEO (think girl boss Jeff Bezos) began an affair with her 20-something-year-old male intern? Except in the case of Romy (Nicole Kidman), what she seeks from her husband (Antonio Banderas) and finds with Samuel (Harris Dickinson) is an explicit exploration into domination and the limits of where her desires can coexist with the reality of her life. Beyond the similarity in discourse, Babygirl also serves as a film borrowing from a genre long lost to time (or Hollywood executive greed). The erotic thriller of the late 1980s and 1990s was a fundamental part of how female sexuality and eroticism were understood on screen. Notable examples include Basic Instinct (1992), Body of Evidence (1993) and Poison Ivy (1992). However, the genre, unfortunately, found itself flailing towards the 2000s as both our access and attitudes towards sex changed over the last twenty years. The value of sex scenes in both film and TV has been hotly debated as an unimportant element of storytelling in recent years, perhaps pointing to a change in our understanding and appetite for sex.

When the trailer first emerged for the film, it immediately sparked complaints that the film was romanticising toxic sexual dynamics (as well as an unseemly age pairing). As Maia Wyman, host of the YouTube channel Broey Deschanel and the other half of Rehash, tells me, “I think a lot of it also comes down to the way movies are being forced to market themselves on social media. Babygirl falls victim to being pushed into this idea of a ‘sexy age gap romance’ and when people hear that their alarm bells go off. The movie is barely about the age gap—if anything, it’s about repression, but they’re falling to the whims of the market.”

I believe that dissecting the sexual politics of both films is a complex yet necessary part of analysing our larger cultural views, but I wonder if there’s also an element of viewers constricting their own experience by holding such strict binaries of what the films represent.

Haaniyah Angus

Much like Nosferatu, Babygirl is about guilt—the guilt of desire and not fitting into a mould of womanhood that seems so easily reachable. However, both protagonists deal with that differently. Babygirl examines repression more directly through Romy’s lens (it is based, in part, on Reijn’s own experiences). Romy is a high-powered CEO who does the triple shift as a perfect wife and mother but feels intense guilt for her desires because they crack the facade she had been building with her husband for 19 years.

Ellen, on the other hand, feels guilt for calling out to Orlok before she even knows who he is or the exact horror that he encompasses. She wishes desperately to be that ideal form of a woman in the same way her childhood friend Anna (Emma Corrin) seems to be—Anna is also married, has two kids with one on the way, she’s doting but quiet around her husband and God-fearing. Anna and Frederich (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) present the cultural idea of what Ellen should be but can’t, and with her arrival into Anna’s home she begins to corrupt their marital bliss. A queer element can be read in the relationship between Ellen and Anna, when they share Anna’s final night together, Ellen thanks her for loving her, and Anna gifts Ellen the cross she’s worn as a form of protection—that same cross is found on Anna’s pillow as we pan down to witness the rats feasting on her body. Thomas also represents this crisis in cultural ideals with his pursuit of masculinity and the jealousy surrounding Ellen’s relationship with Orlok. When Orlok possesses Ellen during their confrontation he mocks Thomas with knowledge that Thomas could never please her as he does. That mockery leads to what some may see as a passionate embrace between the couple to rid themselves of Orlok and shame or perhaps, Thomas pushing himself onto Ellen just as Orlok had been doing for years.

I believe that dissecting the sexual politics of both films is a complex yet necessary part of analysing our larger cultural views, but I wonder if there’s also an element of viewers constricting their own experience by holding such strict binaries of what the films represent. As a film critic, I’ve found myself getting more disillusioned with online film discourses the older I get, perhaps that’s age or common sense setting in but either way it makes engaging with film so much less enjoyable. Romy in Babygirl finding freedom from repression within domination is not the film telling you, the viewer to do the same. Ellen, making her final choice to embrace Orlok, is not telling you the viewer that the film is ‘romanticising’ their relationship. This isn’t to say that the choices made by either character exist in a vacuum outside of the influences of trauma, abuse, and patriarchy, but I believe that these are worthwhile explorations that push us to discuss not only our desires but where they come from. Both films, were on the top end of the list for 2024, so maybe take it with a grain of salt, but sitting with those uncomfortable feelings left me understanding myself so much more than if they hadn’t even tried at all.

Continue reading — “I live like a nun”: Halina Reijn on Babygirl