David Lynch expert Andy Hazel pens a fond farewell to the master of cinematic surrealism, who passed away last week at 78 years-old. He leaves an insurmountable legacy in his wake.

“One of the things I’ve learned is that this trip through life is to gain divine mind through knowledge and experience of combined opposites. And that’s our trip. The world we live in is a world of opposites. And to reconcile those two opposing things is the trick. The middle is not a compromise… it’s the power of both.” — David Lynch (Lynch on Lynch, 1993).

David Lynch’s work always began with an idea – unformed but alive, requiring the quiet resolve of an artist to bring it into being. The product of Missoula, Montana, and an Eagle Scout by his own description, Lynch maintained that his art was not, as some critics charged, “weird,” but an honest reflection of thoughts and dreams that many could understand, if only they allowed themselves.

Honing these ideas through extensive study at three different fine art academies, from the outset Lynch demanded complete creative control over all his projects. A combination of academia and hard-headedness virtually guaranteed to doom anyone looking to make headway in Hollywood. Despite this, his ten feature films have touched on almost every major film and television movement of the last fifty years. The 1970s midnight movie reached its zenith with Eraserhead. Prestige cinema of the 1980s was rarely better than The Elephant Man. The modern noir was reconfigured by the visceral power of Blue Velvet and television was upended in 1990 by Twin Peaks, its boundaries reconfigured again, 25 years later by season three. His 2001 film Mulholland Dr. remains the most acclaimed of the twenty-first century, a hypnotic exploration of dreams, identity, and Hollywood itself.

Lynch surprised audiences over and over with the power that comes from piercing through the layers we had grown accustomed to expecting between inspiration and artwork. He personally shaped every aspect of his medium: scripting, sound, lighting, casting, performance, production, editing. In the case of Mulholland Dr. this extended to handwritten advice for cinema projectionists, asking for extra headroom and a slightly “hotter” sound mix.

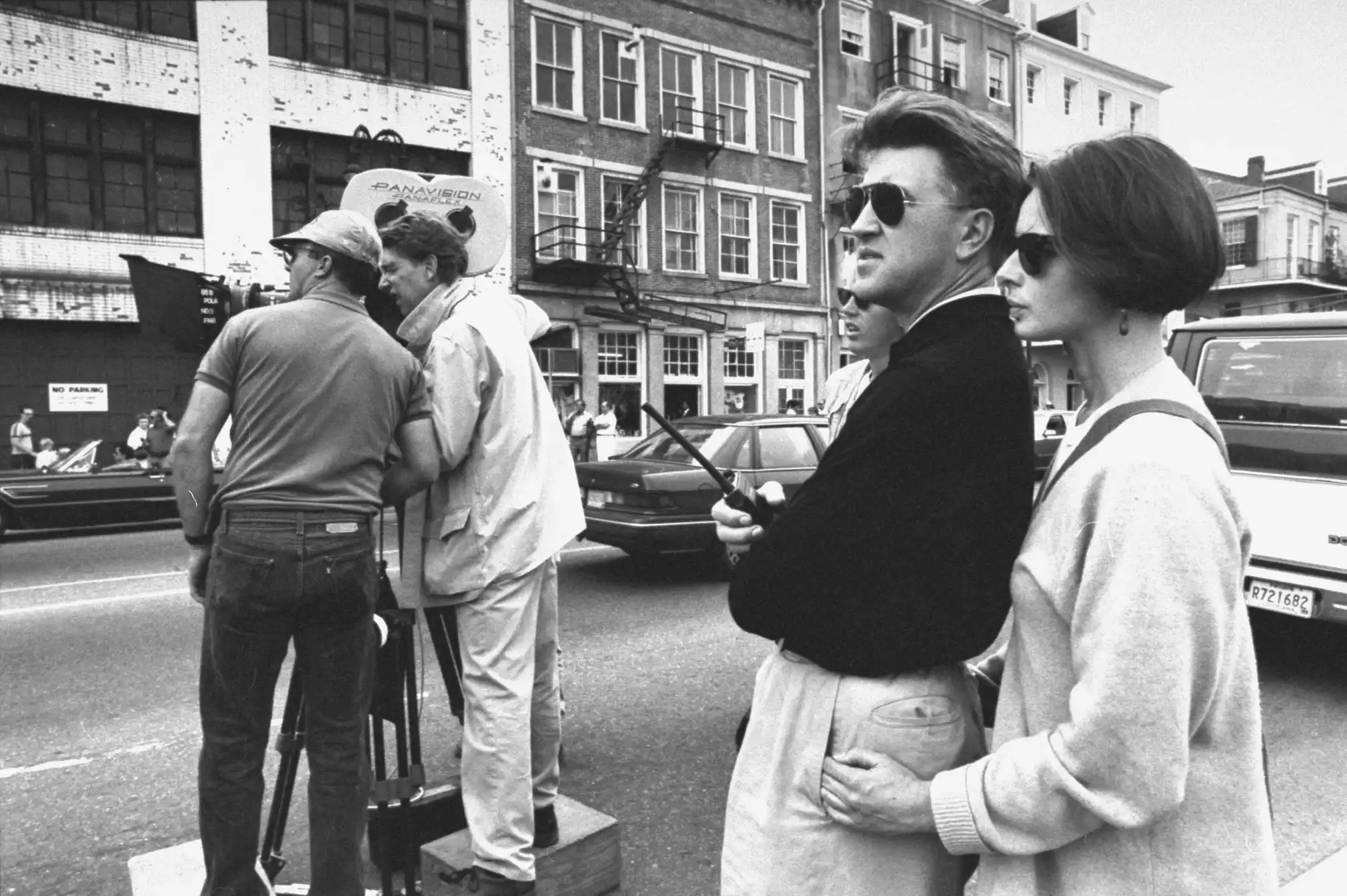

David Lynch and Isabella Rossellini on the set of Wild At Heart (1990).

For Lynch, an idea could linger for years, or it could be realised on the set. Yet when he was forced to cede creative control, for his 1984 adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune, there is every chance we would have been robbed of the career that followed, a staggering body of films and television that gave him the freedom to pursue other projects. Across almost every conceivable medium, each work offers a path back to the original, unfiltered point of inspiration. When I last spoke to him, in 2021, he enthused about his newfound love of cross-stitch. The greatest tragedy, he intoned gravely, was an idea that got away, a dream that was forgotten. The inspiration came first. Then the medium. Even his most widely seen and acclaimed creations, Twin Peaks and Mulholland Dr., exist between the two realms of television and cinema. There is literally a moment in the latter where it turns from a rejected television pilot into pure Lynchian cinema, a term that David Foster Wallace described as “a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter”. Bruce Springsteen called it a style that exploited “superficial normalcy” and hidden desires of “regular people”.

When asked to describe himself, Lynch always emphasised his regularity, a move that only reinforced the belief of those who labelled him “weird” and found his films and art alienating and unsettling. We all dream, so subconsciously, we are used to storytelling moving free of conventional narrative and accept unconnected events happening in sequence. On this level, it is storytelling in its purest form. It is telling that Lynch’s films, unlike many other American filmmakers of his era, were often embraced overseas more often than in his homeland.

In 2018, I hosted an Australian touring event called Twin Peaks: A Conversation with the Stars. Twin Peaks producer Sabrina Sutherland and many cast members of the original series talked about their experiences on the show and working with Lynch in front of hundreds of enthusiastic fans. The cast were full of love and appreciation for the man who brought them together, and Lynch joined via Zoom from his workshop in Los Angeles. Behind him sat unfinished sculptures and woodwork as he sat gazing down at us and giving his famously curt answers to inquiries about his life and his art. “What is happening in Twin Peaks right now?” I asked. “A great deal.” he honked in reply. He wasn’t going to elaborate on that. Both Lynch and the cast spoke solemnly about the third season’s close association with memory, death and the expectations of those who shared Lynch’s love for the town and the series. Lynch, the guests on stage and many in the audience grew emotional when talk turned to the performance and death of actress Catherine E. Coulson, who played The Log Lady. Few works of art in history presage their creator’s own death more powerfully than the 18 hours of Twin Peaks season three. Characters speak openly about the death of others, of their way of life, of themselves. Many actors died shortly after filming their scenes. To create an environment in which such openness and vulnerability was possible speaks to Lynch’s power as a creator and director and utter absence of cynicism or sentimentality. It also speaks to the trust he engenders, and the phenomenon by which anyone you meet who has met Lynch felt blessed by being a recipient of his attention. In the days after his death, social media was full of accounts of gratitude, grace and humour.

David Lynch, Justin Theroux and Laura Harring on the set of Mulholland Drive (2001).

When it came to making films, few filmmakers were as open and generous as David Lynch. He has written and spoken extensively about the importance of art, of finding ideas and of staying true to them. Core to this philosophy is Transcendental Meditation: Two daily twenty-minute sessions of focused peace, guided by mantra. Lynch always credited this as the reason he was able to generate, and had the energy to realise, so many ideas. The calm offered by T.M. also emboldened him to tackle the root causes of the evil that was corrupting the souls of his characters. It was this stark rendering of violence, abuse and horror that marked his works and drew passionate fans, identifying with his honesty and non-exploitative depictions of violence against women. For many, the authenticity of his depictions sparked personal journeys of healing and recovery and built a community in his fandom that were united by a traumatic personal history, making his passing even more difficult.

Personally, I was at the right age, a questioning and curious teenager, to decide that “What would Dale Cooper do?” was a great philosophical approach to life. At first, it involved problem solving with both an analytical and open approach, listening, accepting people without judgement, engaging with the world more fully. More aware of things I could not see. Later, this influence extended to hosting a podcast about Twin Peaks and forming a band that played music from the series. Lynch’s stories encouraged connection, contemplation, and an appreciation for the complexities of existence and later, a steady reliance on black coffee. I am one of thousands of people whose life was transformed by his work, confronting and comforting. Suffering, horror and violence always served a larger purpose, even when the humour, lightness and a warm humanity seem frail when isolated against the darkness of the modern world.

When people look to illuminate these depths, it is poetic to turn to his final works. His scene in Steven Spielberg’s 2022 film The Fabelmans, in which Lynch plays John Ford, is the second last scene in the film, and a powerful on-screen send off. Lynch’s Ford instructs the young Spielberg to see the world different, and to always keep things interesting. As a director, a storyteller in control of his environment and with complete creative freedom, he left us with Laura Palmer’s reality-rendering scream at the end of Twin Peaks. A moment that unified light and dark, the present and the eternal. Opposites. Both.

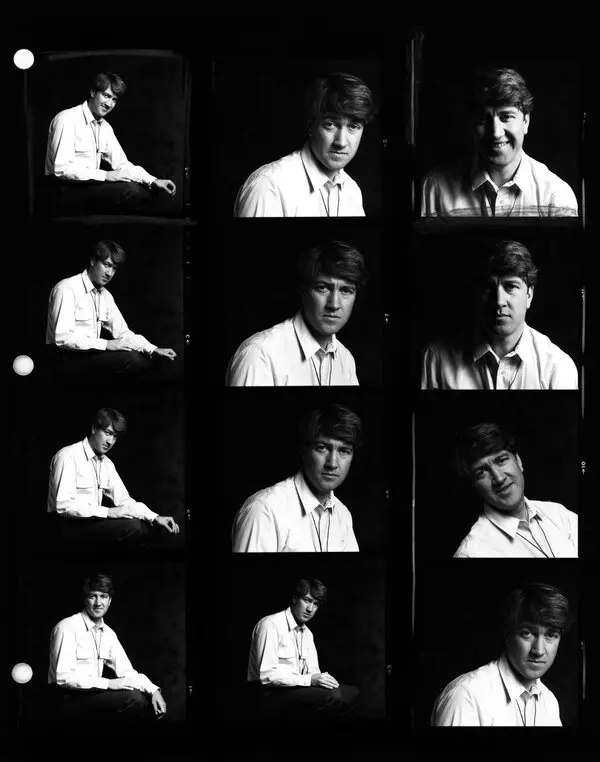

David Lynch on the set of Eraserhead (1977).