“It’s a place where they’ve taken a desert and turned it into their dreams.” In light of the devastating Los Angeles fires, Hannah Benson argues that the Steve Martin-starring rom-com L.A. Story demands a rewatch.

I live in Los Angeles and there’s a shot from the 1991 satirical romantic-comedy L.A. Story that I keep coming back to this week. It captures the film’s star and screenwriter Steve Martin standing before a freeway sign that reads, ‘L.A. Wants 2 Help U”. In the wake of the city’s devastating fires, from the coast in the Pacific Palisades to the tree-lined streets of Altadena, it’s quite clear that this sentiment goes beyond something that only happens in the movies—it’s a truth.

Los Angeles is not an easy city to live in. The rents are high. At times the cost of groceries seems higher. Its more recent inhabitants are gentrifying the neighbourhoods of those who have lived in them since the beginning—neighbourhoods that hold so much culture and history that whole books could be written about every single block. The traffic and infrastructure is hard on car engines and friendships. Loud and bustling, yet very little businesses are open past 9pm. And it’s always finding inventive ways to break the hearts of actors, writers and creatives via email.

The only way to truly live in Los Angeles is to hold out hope that the sprawling town does indeed want to help you. Just like weatherman Harris K. Telemacher, Martin’s character in L.A. Story, you don’t know how or when, but it’s believable.

Martin, while not born in Los Angeles, is allowed his takes. He’s a UCLA dropout and former Disneyland employee. He’s thanked on the dedication pages of Eve’s Hollywood (1974), the first book written by one of the city’s very best literary champions, Eve Babitz. And of course, one can’t talk about Los Angeles without bringing to mind Martin’s industry: entertainment.

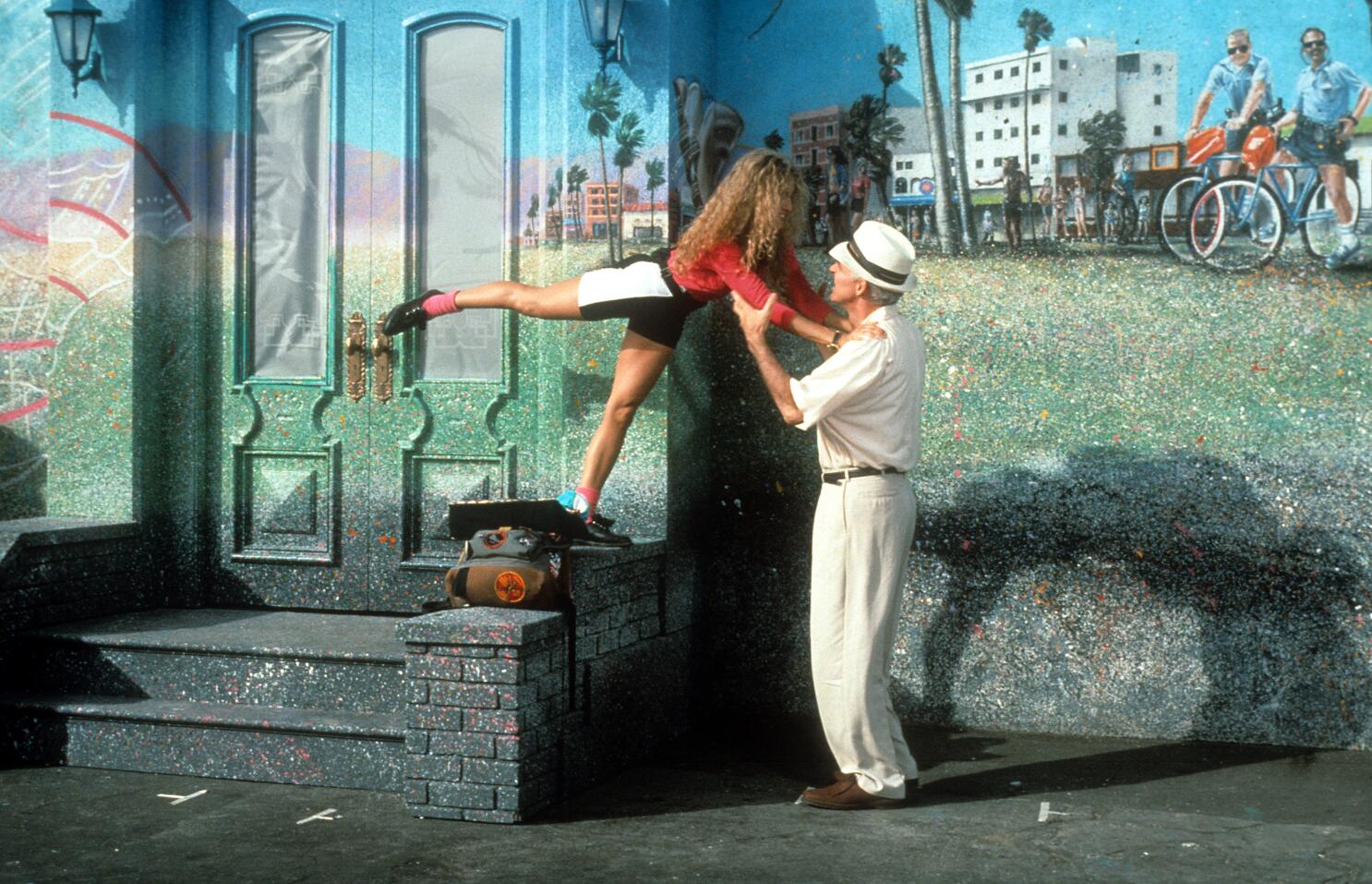

L.A. Story’s romanticism goes beyond a lingering stroll through Hollywood Forever Cemetery and a hot dog floating in the sky set to Charles Trenet’s ‘La Mer’. The female lead and main love interest is played by Victoria Tennant, Martin’s wife at the time. Tennant’s role, Sara McDowell, is as a British journalist chronicling Los Angeles. Studying the city, she muses, “It’s not what I expected. It’s a place where they’ve taken a desert and turned it into their dreams.” As her character finds charm in Los Angeles, so does Martin’s. L.A. Story exemplifies that great phenomenon of rediscovering your city as you show it to someone new. That falling in love is often a testament to where you live.

Considered by many as Eve Babitz’s best work, Slow Days Fast Company (1977) speaks to this idea. Babitz wrote, “People nowadays get upset at the idea of being in love with a city, especially Los Angeles. People think you should be in love with other people or your work or justice. I’ve been in love with people and ideas in several cities and learned that the lovers I’ve loved and the ideas I’ve embraced depended on where I was, how cold it was, and what I had to do to be able to stand it. It’s very easy to stand L.A., which is why it’s almost inevitable that all sorts of ideas get entertained, to say nothing of lovers.”

The only way to truly live in Los Angeles is to hold out hope that the sprawling town does indeed want to help you. Just like weatherman Harris K. Telemacher, Martin’s character in L.A. Story, you don’t know how or when, but it’s believable.

Hannah Benson

Fourteen years later, Martin narrated the final line of L.A. Story: “Romance does exist deep in the heart of L.A.” The comedy does not represent all of Los Angeles. No character is seen pondering a Chicano mural. Ma’amoul crumbs are never brushed aside after a trip to a Lebanese bakery. There’s not a single shot of the historic Black neighbourhood of Altadena. And no one ever suggests grabbing some cold sesame noodles in the San Gabriel Valley. There’s little-to-no acknowledgement of non-white L.A. This is a white, upper-class L.A. story. Martin decidedly (and perhaps wisely) takes on the Los Angeles he represents: the one of image. The impossible dinner reservations. The mid-career crisis. The frivolity.

The city of movies, while the ultimate muse, can be difficult to pin down in a feature-length film. But comprehend its charm and hope, that Steve Martin had the means to do.

Los Angeles only exists because its inhabitants maintain an incredible capacity for hope. Understandably so, those very people are donating their time and effort to help their own. Local restaurants are providing free meals to evacuees and first responders. Comedy venues are fundraising with 100 percent of the proceeds going to the displaced. Theatres are halting their programming to show kids movies, allowing the parents to regroup. Volunteer opportunities at donation centres are filling up, hitting max capacity before midday. All involved are acknowledging the point of Los Angeles: its people.

L.A. Story relies on a certain bit of fantasy to push its plot along. The freeway sign is a sentient being after all. At the film’s climax, the sign manages to save the day and bring the two central characters back together. The kind of fictional magic that elicits the viewer to think, ‘Well, if that’s going to happen anywhere, it would be Los Angeles.’ A town of dreamers.

If a city is only as good as its people, then Los Angeles will be more than okay, because L.A. Wants 2 Help.

See here for information on how to help victims of the fires