“The stage is the only world she can live comfortably with.” Writer and former opera singer Lauren McQuistin reflects on Pablo Larraín’s portrait of Maria Callas, which—split between Maria, the person and La Callas, the star—shows the loneliness of performance and the void that comes with it.

Most people with even a passing knowledge of opera know that Maria Callas, the only opera singer to achieve celebrity status, died of a broken heart, alone in her Paris apartment at age 53. Callas is one of opera’s most enduring icons and for young performers a cautionary tale. Most singers will be told at some point in their studies: ‘If you can do anything else—do that. This career will take everything you have.’ Maria Callas’ life and death are given as a cautionary example. How badly do you want this career, to live for art, for something that can’t love you back?

Like many performers of her calibre, Callas existed in a personality split. ‘Maria’ the woman with everything a woman feels, and ‘La Callas’ the performer, laden with mythology. In Maria, Pablo Larraín’s reimagining of the final week of her life, she is neither simply a wilted diva nor a caricature of a prima donna—Angelina Jolie depicts a Callas where both ‘Maria’ and ‘La Callas’, exist inseparably as the essence of who she is, and both becoming more lost to her in her last days.

During the showreel of Callas’ most iconic roles that opens the film, it is clear Jolie carefully studied Callas’ gestures, leaning into the dramatic technique that heralded Callas as the greatest singing actress of all time. With seven months of vocal training, as opposed to a lifetime of devotion, Jolie—supported by the electricity of a live orchestra and audience—does a suitable job of embodying the knife-edge of making art with your entire body. Jolie’s savage, commanding beauty is captured perfectly in the intimate close-ups of her lip syncing Desdemona’s ‘Ave Maria’.

The grandeur of La Scala, Covent Garden and The Met is then condensed into Callas’s exquisitely opulent apartment, enormous against her frailty. Steven Knight’s biting dialogue is delivered with uncannily accurate posture and poise, Jolie captures her purposeful way of speaking, dry wit and uncompromising nature, alongside her more morose reflections on the past and her present living in her former glory.

Biographer Lyndsey Spence reported from health records that Callas had a nervous breakdown in early 1958, after which she was propped up chemically to keep up with the demands of her career. This ultimately led to drug addiction, alongside her dramatic weight loss in 1954 that turned cruelly into a speculated eating disorder. This is all alluded to in Maria, as her butler (Pierfrancesco Favino), and her housemaid Bruna (Alba Rohrwacher) track her medication and try to convince her to eat, as she cryptically instructs them to move the piano, and hide the ashtrays for an interviewer.

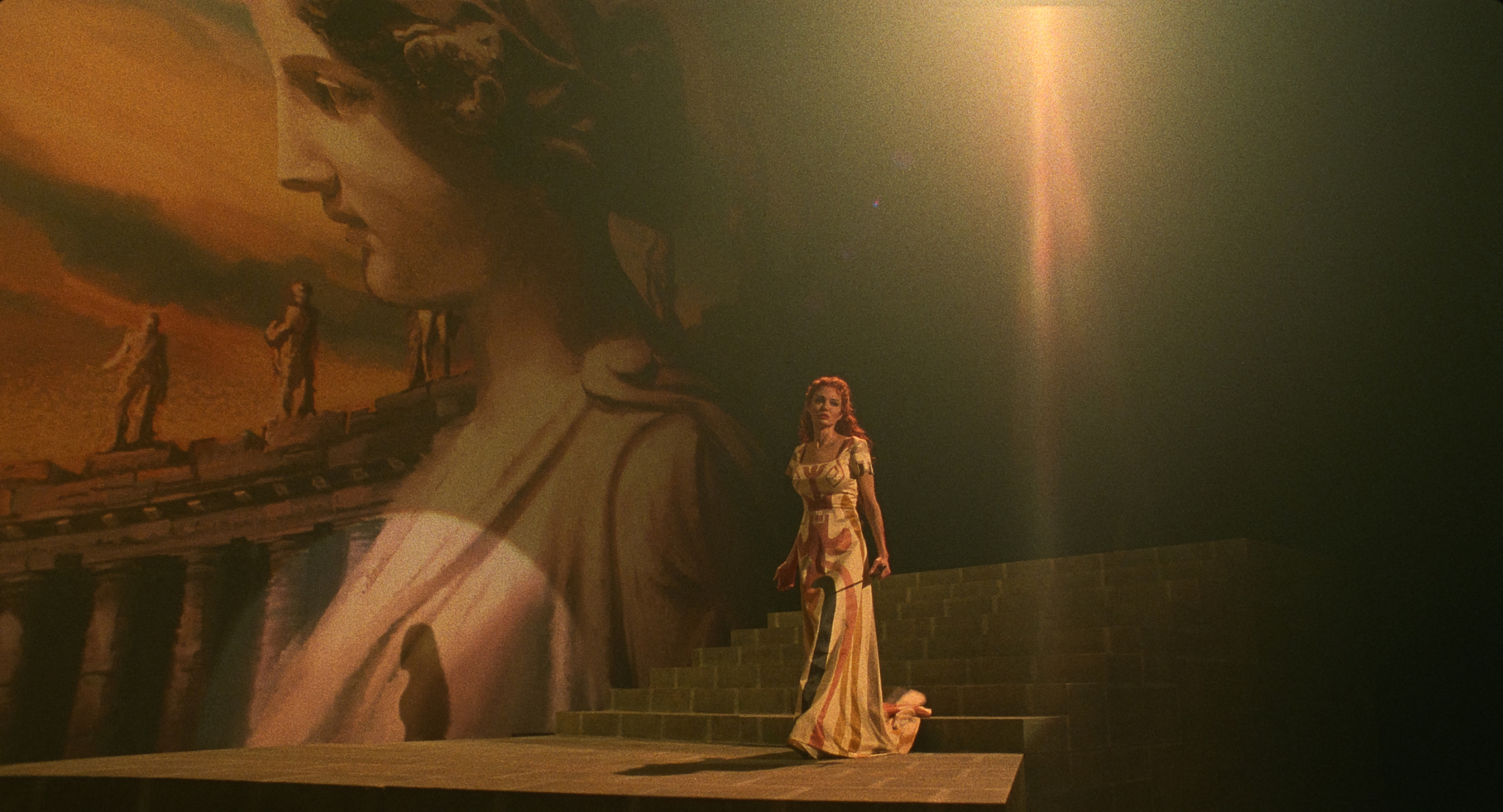

Angelina Jolie in Maria (dir. Pablo Larraín)

Underpinning many performers’ careers is what Robin Williams described as a ‘please love me syndrome.’ Though Callas sits visibly outside cafes because she is ‘in the mood for adulation’ it is the vulnerable, exposed Maria, singing ‘Casta Diva’ in her fading voice for Bruna (asking ‘how was it?’ with a child’s earnest sincerity) that exposes the reality underneath it all. All performers want to be seen, approved of and loved. She no longer enjoys the audience applause which felt like someone loving her back; Aristotle Onassis, now dead, couldn’t love her back. Performance is emptying yourself, often leaving yourself with nothing—a performer exists in a character, very rarely sitting with themselves as a person. If the performer achieves fame, it’s their public persona that receives the praise their innermost self is seeking. It’s in those moments that the relief of drugs feels like something loving you back.

Speaking to an interviewer (Kodi Smit-McPhee), a figment of her imagination named Mandrax after her sedative of choice, Maria is articulate and effortless, explaining how on the good days performance is intoxication, and on the bad days a confirmation of your perceived inherent unworthiness. However, the stage is the only world she can live comfortably with, as she walks through Paris, the pedestrians become a chorus, her imagination and drug use filling in the gaps of daily life to create a reality she can understand and tolerate. When the chorus disappears and the music ends, she carries the uncertainty of a lost child.

With flashbacks of her mother pimping her out—both voice and body—to Nazis, we meet an unprotected child who couldn’t say no, juxtaposed against La Divina, who shouts at cafe owners to turn her recordings off, and refuses to call her doctor, though her Butler pleads. Callas was renowned for her ‘difficult’ personality, however Larraín adds humanity to this narrative. He portrays a woman desperate to make her own choices, and claim what agency she can. In her head, Mandrax tries to force her to sing, and she refuses, saying she will sing when she wants to. However, even in this non-reality, when she dons the costume of Cio Cio-san—star of Madame Butterfly—she is unable to open her mouth.

Art can be a healing outlet for many people, but for performers it often tugs on unhealed wounds, Maria shows us the heartbreak of a woman who becomes the most famous soprano in the world, but still wrestles with the self-hatred her mother laced into her.

Lauren McQuistin

Maria also accurately captured the fact that a performer can often only see themselves through the eyes of the people watching them, Callas can tell her story with ease when she feels like she’s being interviewed, but when in regular conversation, she tells her sister (played by Valeria Golina) she doesn’t know if she’s real, she is simply not present for her own experience. So it is for performance, so it is for a dependency on drugs.

Art can be a healing outlet for many people, but for performers it often tugs on unhealed wounds, Maria shows us the heartbreak of a woman who becomes the most famous soprano in the world, but still wrestles with the self-hatred her mother laced into her. Puccini’s ‘Vissi D’arte’ (I lived for my art, I lived for love…why, why, o Lord, why do you reward me thus?) was the obvious and perfect swan song. People listen awestruck from the window as she sings herself to death. With what she has left of her voice she pours the aria from her, knowing it will kill her, but much like Cio Cio-san, Wally and Tosca, on her own terms.

Maria, much like her public, appreciates Callas for her art and is fascinated by the glamour and tragedy of her personal life. It acknowledges her fame, voice, and personal pain, but fails to explore that for opera fans, she was not simply an adored, enigmatic and tragic singer—but an artistic talent like the world had never seen. It doesn’t explore the collaborations with Tullio Serafin and Giuseppe Di Stefano, her press-orchestrated rivalry with Renata Tebaldi, or her Juilliard Masterclasses that proved she was both a technician and philosopher. It’s not until the archival footage at the end that we see Callas as a lover of life, who took a forkful from everyone’s plate at dinner and who didn’t only go to her own singing lessons but sat in on everyone else’s for the love of art and to develop her craft. However Maria still manages to give a sincere nod to the Tigress’ vulnerability, and venom, and how they often are two sides of the same coin.

Maria is in cinemas now