Fatima Khan speaks to filmmaker Usman Riaz about his debut feature The Glassworker, creating Pakistan’s first animation studio and his visit to Studio Ghibli in Japan.

Fatima Khan: When was the first seed planted to create Mano Studios?

Usman Riaz: The studio was built to make the film, so as soon as I began drawing and writing the film I knew I had to build a studio. Mano was the name of my cat actually, I named the studio after him.

FK: Why do you think it took so long for someone to come along and establish a Pakistani animation studio?

UR: I kept hoping that someone would start a hand-drawn animation studio in Pakistan. I was ready to join it in a heartbeat, but that never happened—there’s no infrastructure for animation in Pakistan, it’s not taught in schools. However, my mother is an artist and would always be drawing. I was fascinated by it and then of course watching animation and reading comic books I was studying all of those things without realising that I was studying animation.

Ever since I was a child, I was obsessed with animation. I’ve been drawing since I could hold a pencil and playing music since I was four years old; animation has always fascinated me because it was just the amalgamation of all the things that I love, which is storytelling.

FK: Which studios inspired your Mano Studios?

UR: For drawing and music I would say specifically the early works of Walt Disney like Pinocchio, Snow White and Bambi, those films were remarkable. And then of course, Studio Ghibli’s films I loved before I even knew who they were.

My appreciation for all of these things definitely comes from my family and my obsessive nature of getting into things and reading about it and wanting to understand how it works. I grew up watching a lot of behind the scenes documentaries. When DVDs first came out a big part of my home viewing experience was watching the behind the scenes. For example, all of the Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings… and in fact when The Lord of the Rings extended editions came out they had 18 hours worth of behind the scenes content, I learned so much about filmmaking just by watching those. More relevantly, the behind the scenes of Spirited Away—I got to see how Hayao Miyazaki handles making his movies; however, I never envisioned when I was drawing and playing music as a kid that I would ever get older and make my own animated film, but looking back it seems inevitable now.

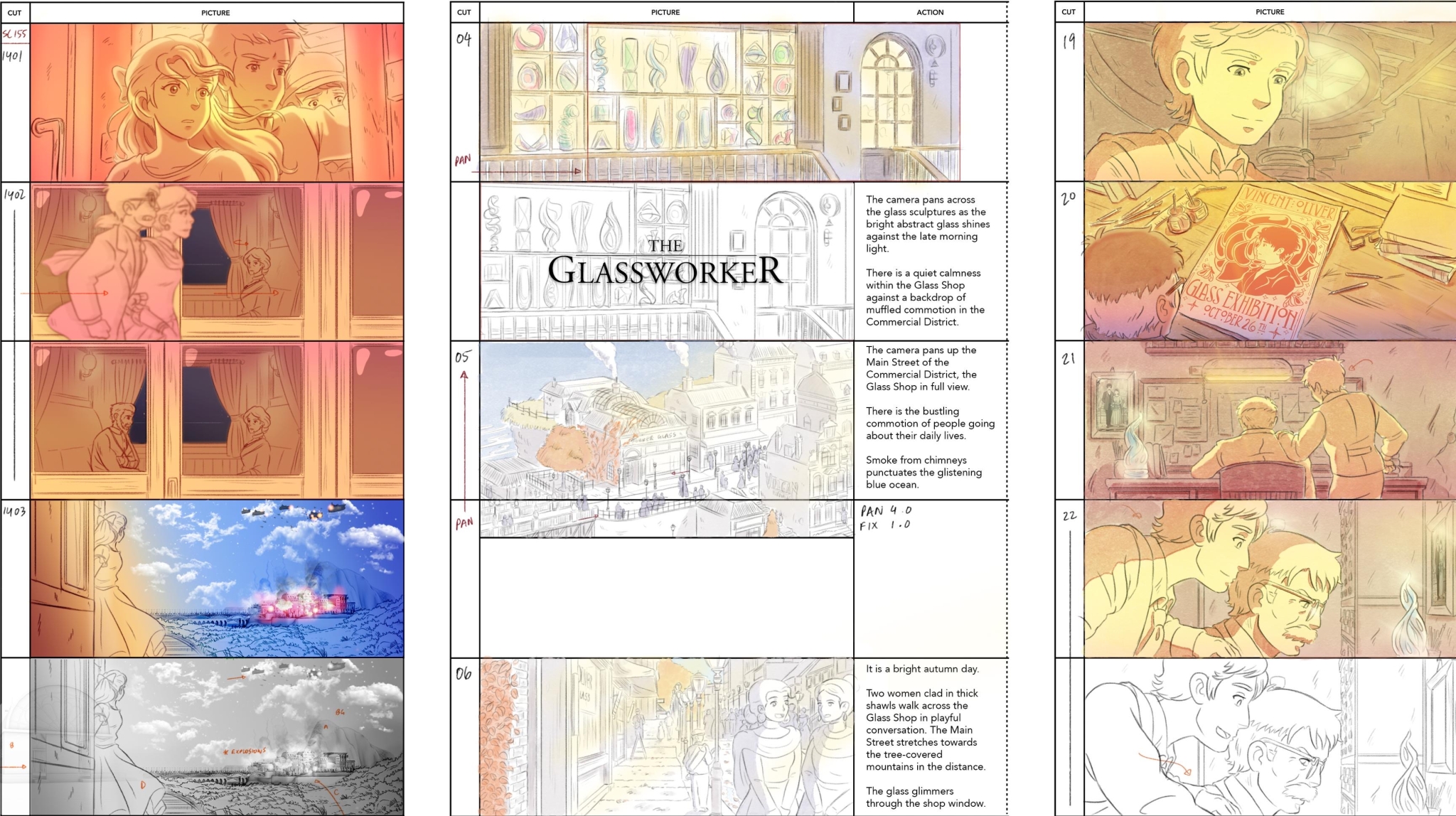

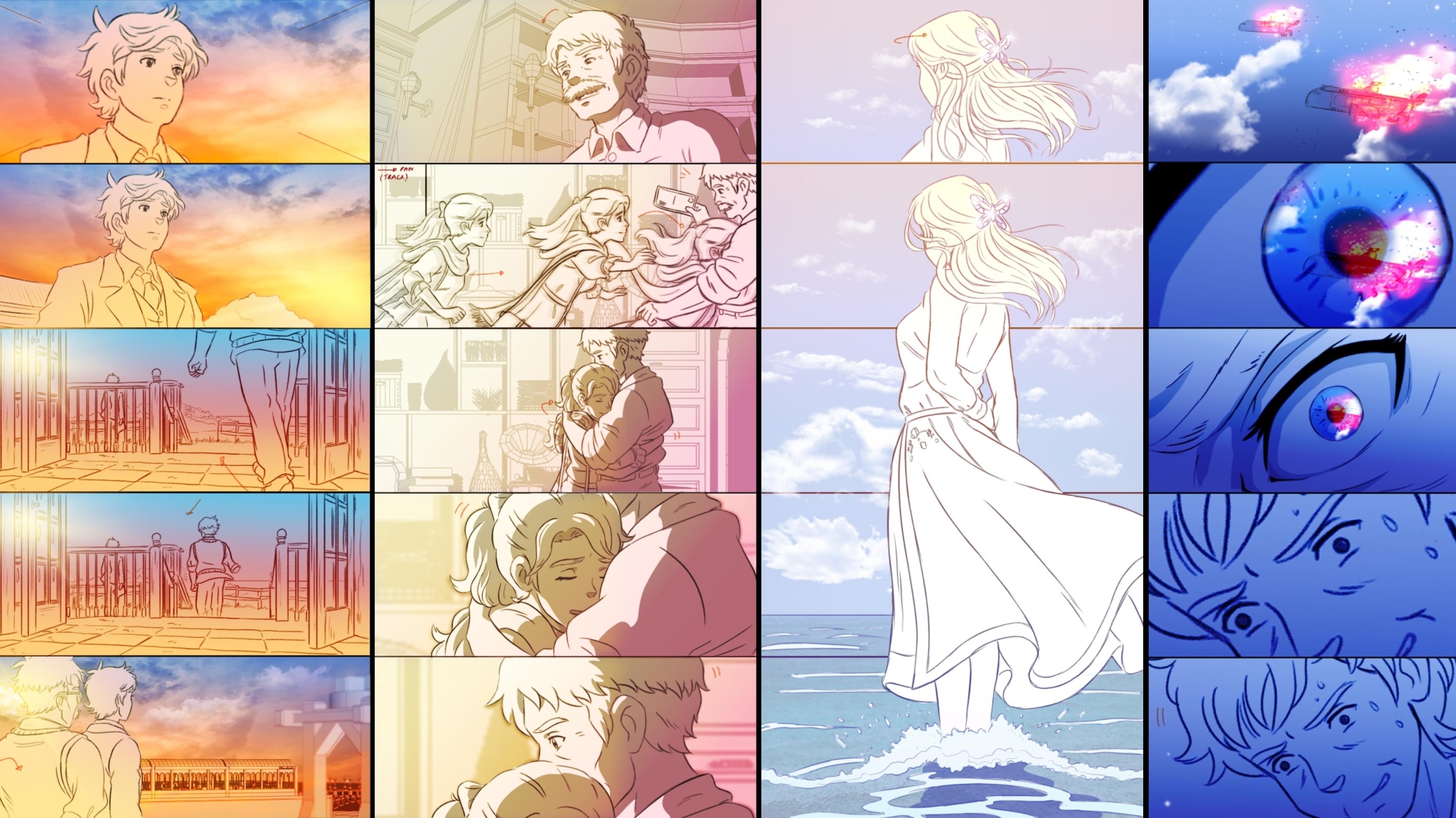

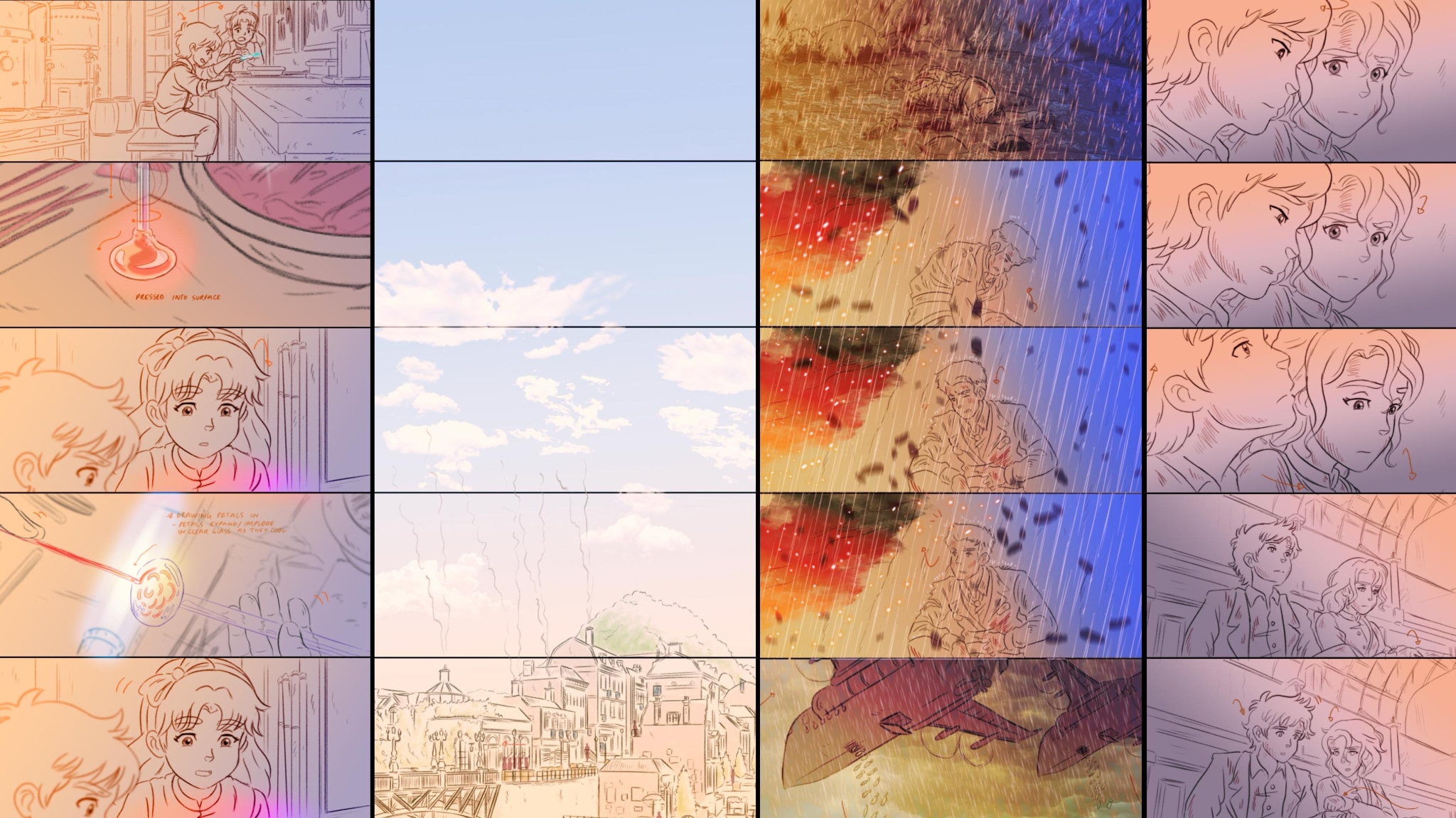

Still image from The Glassworker

FK: You visited Ghibli studios, how did that come about?

UR: When I was one year into the project working on The Glassworker, I managed to convince the organiser of a TEDx event In Tokyo to let me come and speak about animation in Japan and talk about my film, what I’ve been working on and to just pour my heart out about how much I love the animation industry and specifically Japanese animation. The organiser was very gracious to let me come and give the talk in Japan and when that happened, I was invited to Studio Ghibli, which was a miracle. I burst out crying because I never thought I would ever be around these things and able to just see where some of my favourite animated films were made.

So that’s really how I went to Studio Ghibli, which was an eye-opening experience for me. Hayao Miyazaki famously announced that he had retired after making The Wind Rises, so I thought he’s not going to be there. But when I went there, he was working on his short film for the Ghibli Museum called Boro the Caterpillar, I didn’t know that at the time, I just saw him working on something and assumed he’s out of retirement and working on his next film. It was magical. I’m very, very grateful for that experience.

FK: Why was it was important to make a film about the impact of war?

UR: Growing up in Pakistan, the world changed after 9/11 and there was all of this conflict happening in my periphery that I was too young to understand. It was a difficult way to grow up. It was only when I was older that I realised it was not a normal experience. However, when you’re young you’re much more resilient and you find reasons to keep living and keep moving forward. I was 22 when I decided that and I wanted to capture how I felt during that time. Thankfully, I didn’t see any conflict but you always heard about it, you always read about it, you always saw it on the news. I felt like the world could just crumble tomorrow and had to find a way to navigate through that. These feelings were really what I tried to capture in the film, especially with the characters being artists and musicians like myself, but I didn’t want to base the film in Pakistan because I didn’t want it to become any sort of political statement.

FK: The final third gets quite dark.

UR: I wanted the narrative to escalate throughout the film; and as the characters grew, I wanted the story to become progressively darker, much like how Pinocchio in the third act becomes extremely dark, an echoing of what the character is going through. Because The Glassworker is about war I felt we had to show the consequences of everything that is happening around the characters—it was inevitable to go in that direction.

Still image from The Glassworker

FK: Why was it important to use glass as a symbol?

UR: In 2007 a movie called Perfume came out about the art of perfume making which had a dark murder mystery sub-plot. I thought, “okay, we have a movie about perfume, why don’t we have a movie about glassblowing?” Seven years later I decided to make that movie about glassblowing and I just felt that the metaphor of having glass, one of the most fragile materials in existence, set during wartime would be something interesting to explore.

FK: You worked on The Glassworker for ten years, what is it like for it to not be yours anymore, to now belong to an audience?

UR: I view my work as a time capsule. So while it’s surreal that the movie’s done because I’ve worked on it for a decade, I never look back on something like, oh I wish I could go in and fix this, I wish I could go in and fix that, because there’s no point, I won’t be able to. I think it’s my way of rationalising that, within the time frame that I had, this is the best I could have possibly done. And it allows me to view it from a detached point of view, even all the music that I had written and recorded, or the live action short films that I’ve made, I view them as capturing a moment. The Glassworker captured a 10 year moment, so it’s different, but it’s surreal when I share it with people now that it’s finally over, and I feel a lot of gratitude for the process but also the result.

There were a few other enthusiasts like me in the studio—we were able to impart some of that and we would all research together and work on the process. Nobody really had any technical understanding of animation prior to this, but really, I drew everything in great detail so that their inexperience didn’t matter—they had a road map to follow when it came to the animation. And of course, I animated a lot of the film myself. So we did a lot of work, a lot of research and a lot of development to be able to do the animation but then capture the intricacy of glass. And our art direction team did a wonderful job there as well. Mariam Paracha is the art director on the film, the co-founder of the studio, and my wife. We started the studio together.

FK: And now, looking forward to your next project, what aspects of your style would you like to develop?

UR: I want to explore different visual styles for sure. I feel like I got to fulfil a childhood dream, making The Glassworker this particular way, and now I want to find new ways to do things, exciting ways to make art. I’m just grateful that I have been able to make this and whatever I get to do next, of course, I want to keep it exciting for myself.