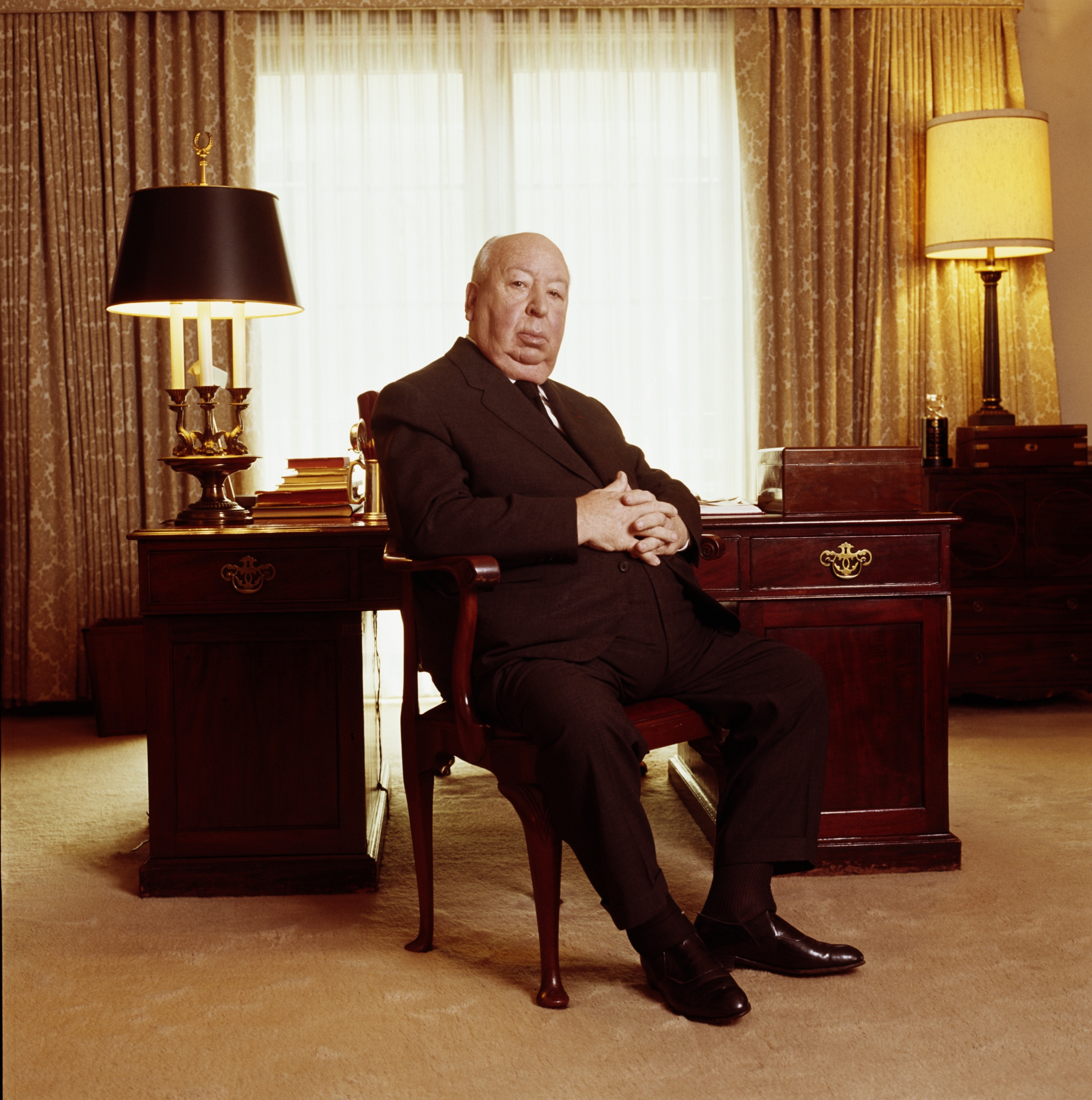

In August 1976, photographer David Montgomery was commissioned by The Sunday Times to go to Los Angeles to shoot legendary filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock. At the time, Hitchcock had already released the bulk of his masterpieces, from Rear Window (1954) to North By Northwest (1959), and Psycho (1960) to Vertigo (1953), and was one of the most famous directors in the world. Talking to A Rabbit’s Foot from his London studio, Montgomery tells the story of his encounter with the Master of Suspense in his own words.

The Sunday Times sent me out to photograph him— Alfred Hitchcock. It was 1976. At the time, photographers would go and shoot by themselves. No assistants. Nobody helped you. Most of the time you didn’t even use lights, you’d just go near a window. It didn’t matter if it was the prime minister. But for Hitchcock, I rented lights. I went out to California, and they didn’t check me into a hotel. I got to LA and every hotel was booked up, so I found a crappy motel run by Iranian rebels. Who knew about Iran, you know? And these guys were gung-ho… I had no idea what any of them were talking about, and I didn’t have much interest either.

So I stayed there for the night, and the next day I went to this studio lot. The shoot took place in a caravan that was fixed up to look like an office… you know… Hollywood. I was in a lot somewhere and I walked through the caravan door and I’m in this fancy office.

I took one look at the man, and, oh my God, he was as big as a whale. I didn’t know where to start. It was like meat seeping out all over… out of his collar, out of his sleeves. I looked at his socks, and it looked like the fat was oozing out of his shoes. I was very lucky at the time because I was shooting a lot of famous people. As far as I was concerned, I was lucky if the subject was photogenic. That made it a little bit easier. But Hitchcock? He reminded me of a rabbit hanging up in a butcher shop. That was what came into my mind when I saw him.

Alfred Hitchcock. Los Angeles, 1976. By David Montgomery

There were very few words spoken between us. “How do you do?” and whatnot. He wasn’t very friendly. But sometimes that’s okay. Sometimes, no matter who it is, the first five shots are the best, or the last 10 shots, or the last one shot. You get thick–skinned after a while, in this business.

David Montgomery

There were very few words spoken between us. “How do you do?” and whatnot. He wasn’t very friendly. But sometimes that’s okay. Sometimes, no matter who it is, the first five shots are the best, or the last 10 shots, or the last one shot. You get thick–skinned after a while, in this business.

The camera I was shooting on was a Hasselblad. When you press the button, the mirror flips up in the camera and it goes black. You never see the picture anywhere else but your mind. I had no idea that the picture I took of Hitchcock was successful until I got it developed a week later. Every photographer had to live with that. I generally work from an unconscious state, and I kinda believe that I’ve got a spirit guide that helps me. If the spirit guide doesn’t help me, then I gotta get real professional. But even from early on, I knew how to light things, so I could always make sure that the lighting was good. That was in my power. And I had my dark room, so I could really print the hell out of a picture and make it look unbelievable, a far cry from what the original frame looked like.

I probably took 24 pictures of Hitchcock and this guy in a suit comes up to me and tells me, “You’re done.” And I thought “You must be talking to someone else.” Me, getting to the place, renting the lights, doing everything by myself, just to be done after eight minutes? I said “I’m not done,” and he replied “Mr. Hitchcock is expecting a phone call.” So I was done. I got a shot of him sitting on the desk, and that’s what was published. But I took about two rolls of film.

Before I left, I slid over to the desk where Hitchcock was leaning, and I start chattin’ him up, thinking maybe I could charm this monster. There was a picture of him laying on the top of the desk. I grabbed it and asked, “Could you sign this please?” He gave me the “Old boy”… he’s British, you know? And he says, “Oh yes, I miss Colchester oysters,” and he starts ranting on about the oysters of Colchester. I thought, “I must be dreaming this whole ordeal.” But he signed the picture.

Alfred Hitchcock. Los Angeles, 1976. By David Montgomery

I don’t know why his assistant cut my time. Maybe they didn’t like me. I was very polite. I wore a suit. I knew I was a representative of The Sunday Times, so I didn’t want this important filmmaker to call them up and tell them I was rude. I’ve had that before, when I wasn’t. But everybody’s different. For the most part, I was always able to go to a place that looked awful, and really capture how the environment reflected the character of the person I was shooting. The truth comes out of a photograph. It can be the wallpaper in the room, the way they dress, the expression on their face, how they’re standing. It’s a silent movie, a photograph. It tells you so much. Jeffrey Archer was one guy who was really difficult, and he was very rude to me. He insulted me, and as I stood there taking the insults, I put a curse on him. Which came true: he went to prison.

Only one shot got published. When you shoot, you’re going for the one good picture. And it could be a minor detail in body language or expression that’s the difference between the good shot and the bad shot. I’m not particularly proud of the picture [of Hitchcock]… I’m happy to forget about it. The proudest picture I took of a person was Jimi Hendrix. Willie Nelson. The Queen. After I shot her, you could send me to photograph Hitler or a mass murderer and I’d be cool.