A Rabbit’s Foot Creative director Fatima Khan speaks with renowned photographer and educator John Ingledew, whose decades of expertise behind the lens and his teachings on the power of visual imagery offer a unique perspective on the rebellious spirit of Britain’s skinhead scene during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

At the heart of this exploration is Looking For Trouble. I want all you skinheads to get up on your feet, a limited-edition photography book featuring previously unpublished images by Ingledew. The book offers an intimate, powerful glimpse into this pivotal moment in British youth culture, bringing together both his iconic photography and the powerful story it tells.

Khan asks her friend and former collaborator about how he captured the raw, untamed energy of the subculture, and asks for his insights into the visual storytelling that defined the movement.

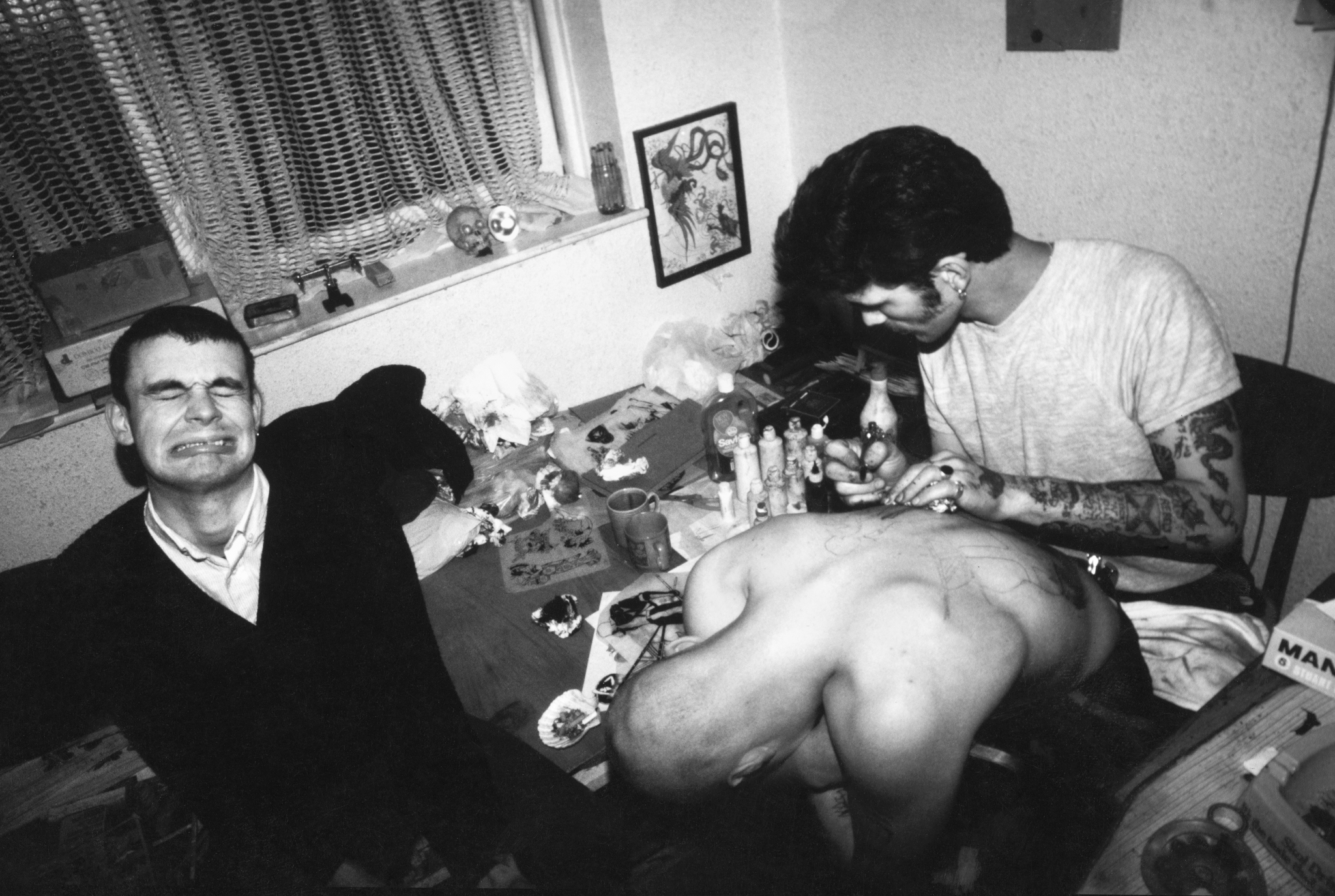

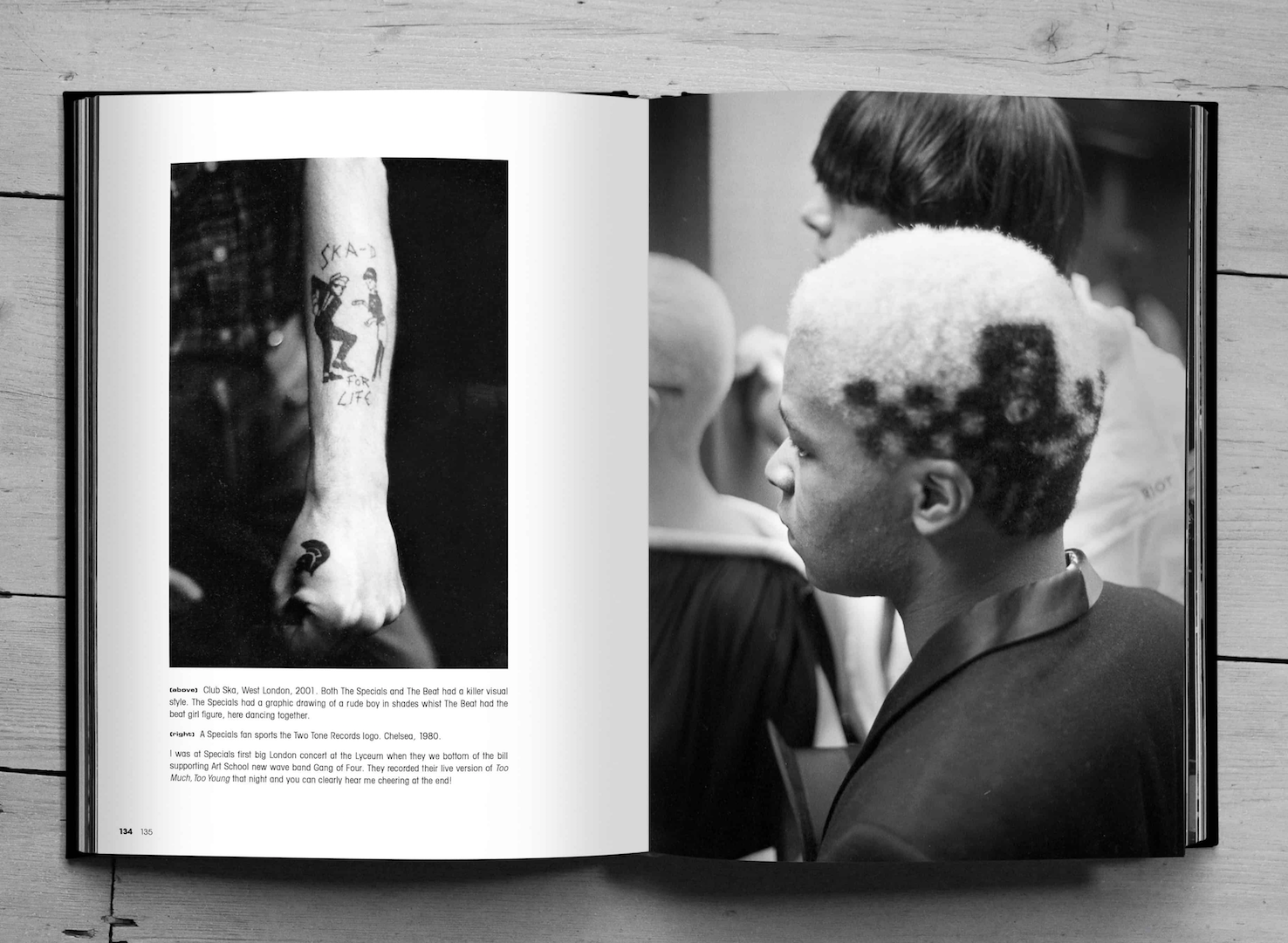

A spread from John Ingledew’s Looking For Trouble. I want all you skinheads to get up on your feet

Fatima Khan: Your book shows a moment in British youth culture during the late 1970s and early 1980s. How did you balance showing the fun and energy of the skinhead scene with the more violent or political sides of it? Was it ever hard to decide what to focus on?

John Ingledew: Britain was in a total mess then, in particular for young people. Government policies caused the nation’s manufacturing industries to collapse so that the only thing stamped ‘MADE IN BRITAIN’ were the foreheads of these incredibly disaffected skinheads. Simultaneously a brilliant new beacon of hope arrived on the music scene as The Specials and Madness bounded on to the scene inspired by brilliant Jamaican ska and rocksteady music of the sixties which countering the nihilism of punk. I wanted to photograph both sides of that moment.

What I loved about William Klein, Bruce Davidson and Diane Arbus and Colin Jones was that they made work in sequences of pictures in books that told much more nuanced stories than single pictures.

John Ingledew

FK: You mentioned being influenced by photographers like William Klein and Bruce Davidson. How did their style affect the way you photographed the skinheads? Were there any challenges for you as a young photographer, especially with the equipment you had at the time?

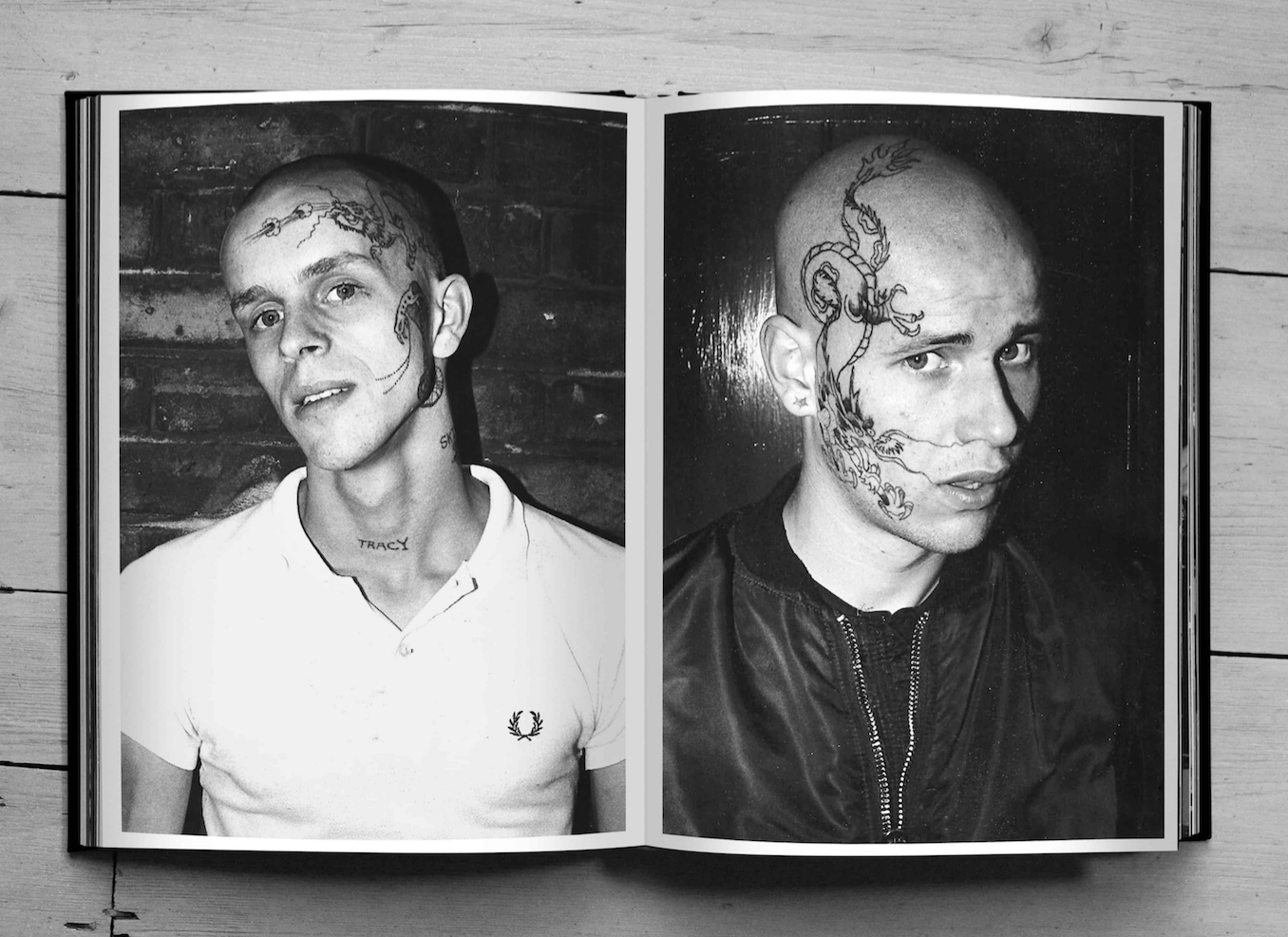

JI: I was only just getting the hang of a camera when I took the first of these pictures as I’d only had my own after getting into Art School aged eighteen. What I loved about William Klein, Bruce Davidson and Diane Arbus and Colin Jones was that they made work in sequences of pictures in books that told much more nuanced stories than single pictures. I was pretty clueless but knew I wanted to make images that were as punchy and striking as the people I was photographing so I tried using flash in daytime like Arbus and printing in dialled up contrast like Klein.

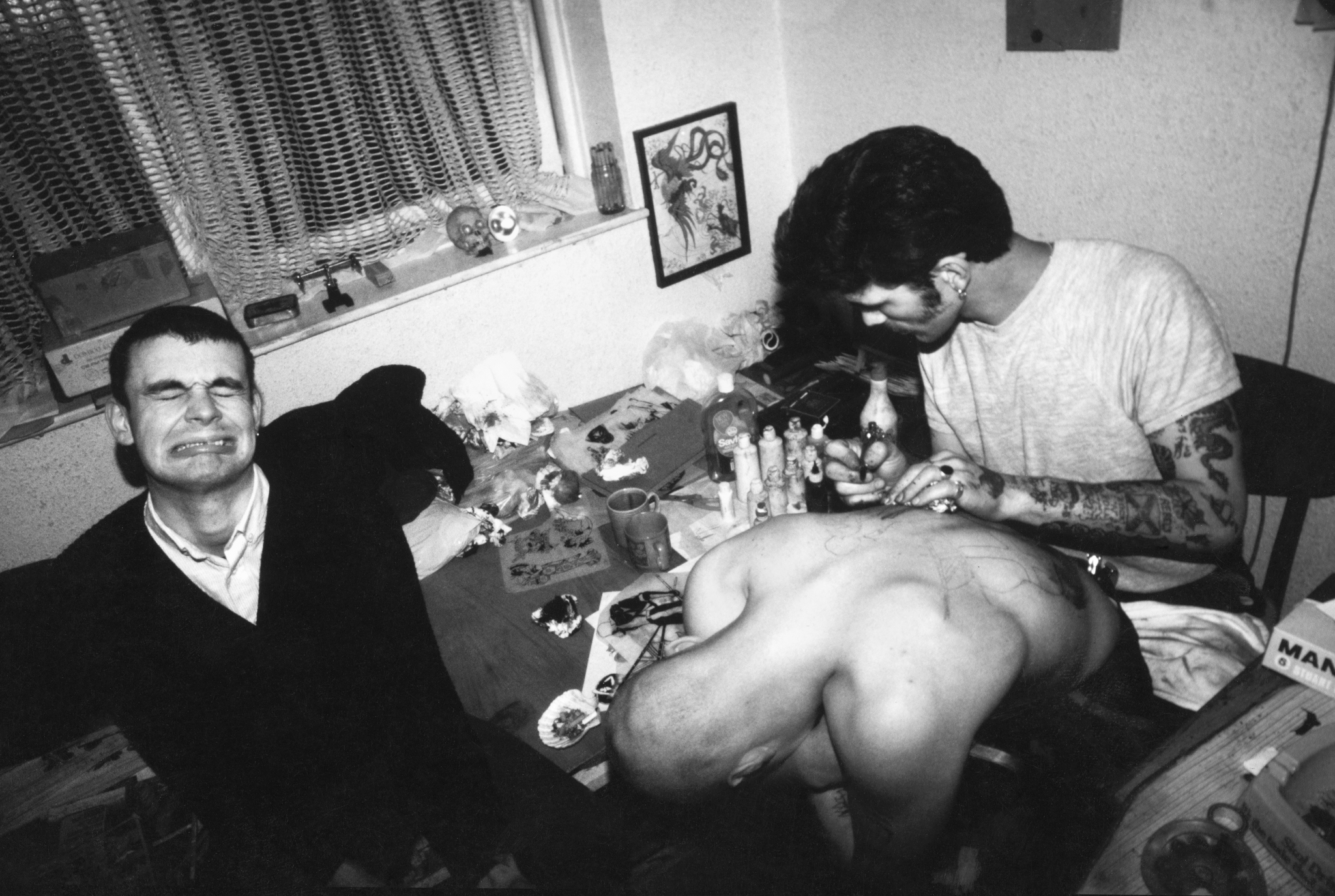

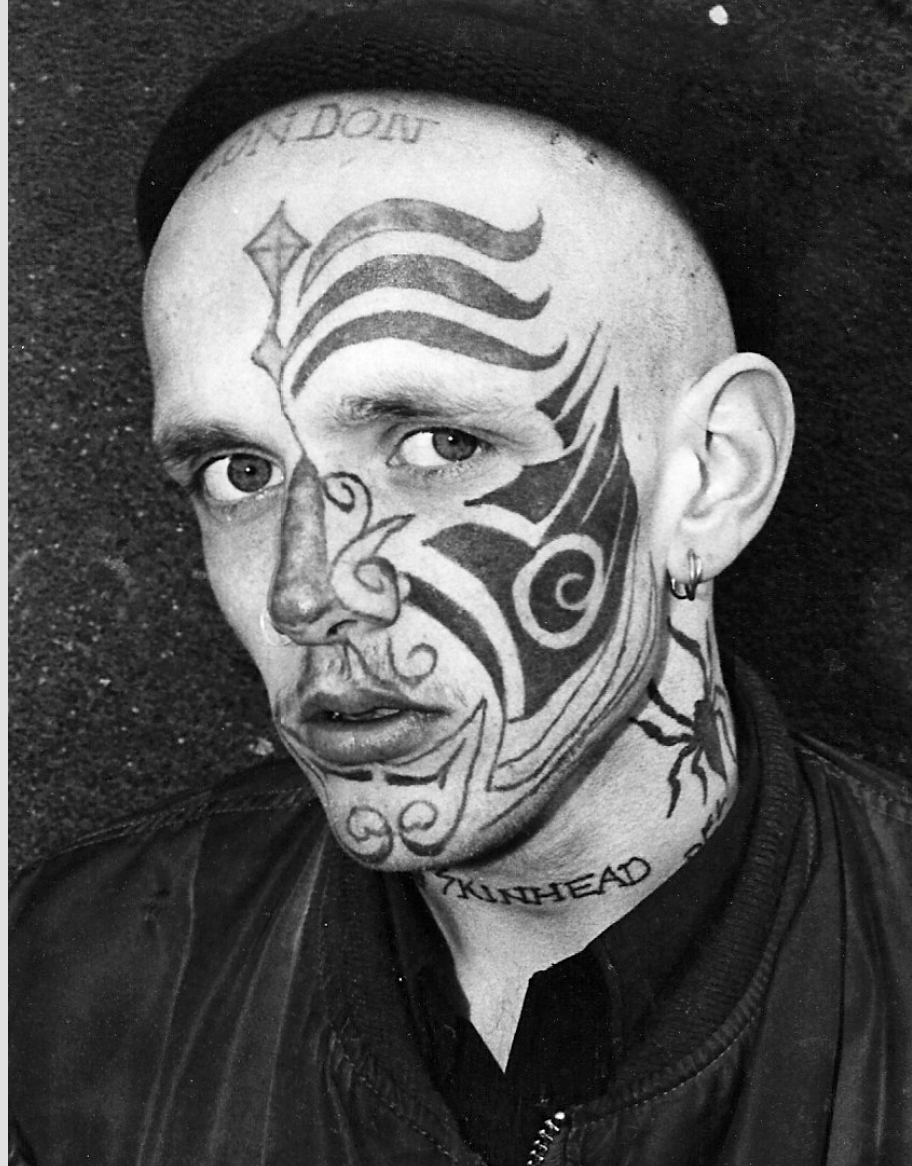

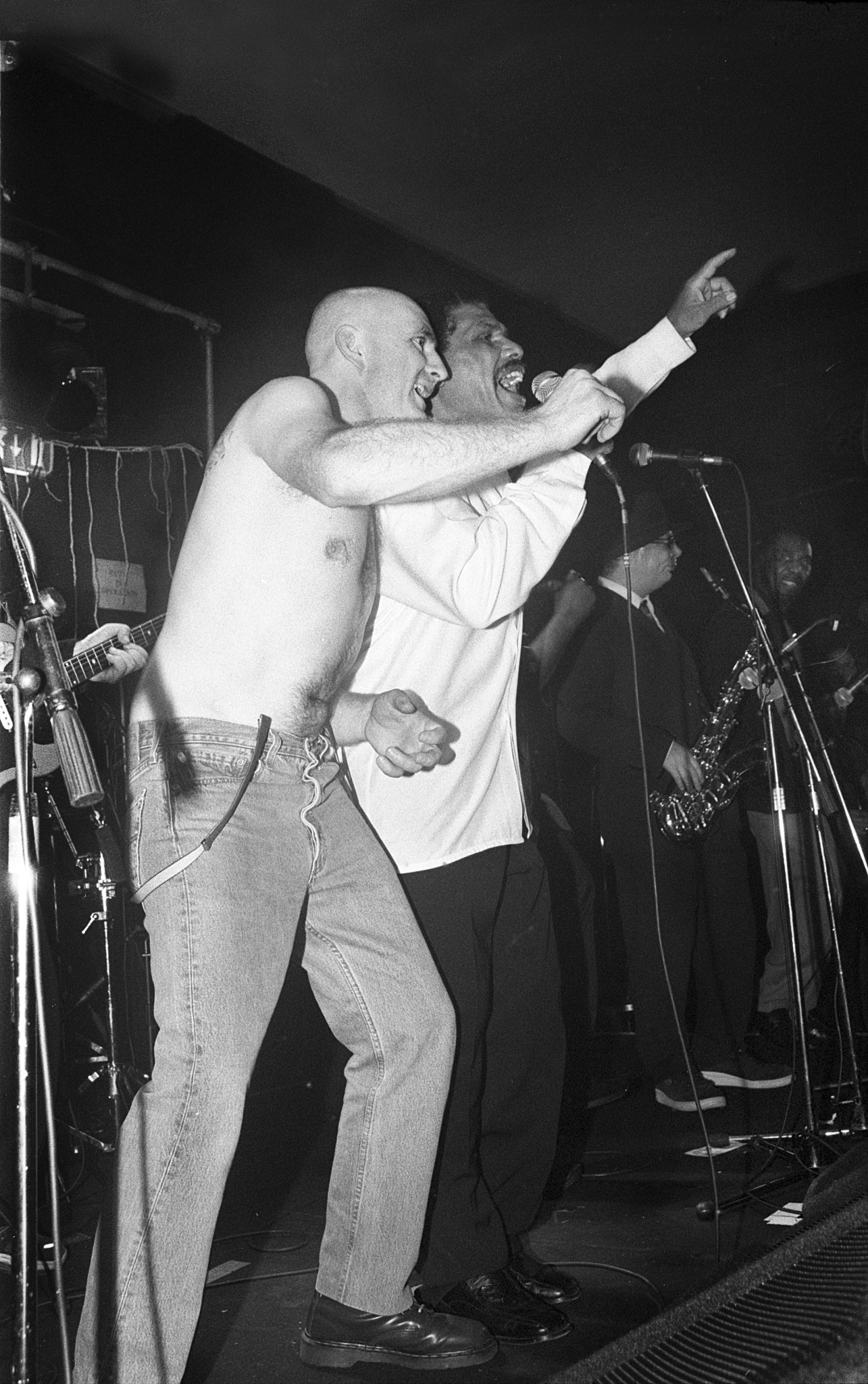

Print from Looking For Trouble. I want all you skinheads to get up on your feet by John Ingledew

FK: Looking at these photos now, what do you hope people take away from them? Do you see your work as a way to preserve that moment in youth culture, or is there something deeper you want people to understand about the skinhead revival?

JI: Youth culture is a brilliant thing, we do it far the best here in Britain. Every kid should be in a gang and have a tribe they love, and that only they really understand, having teenage kicks with great mates before adulthood. Every generation should have their day, have their music, look the part and dance their dance, in this case the moonstomp. I hope my pictures evoke some of that spirit. I also hope readers find the book multi-layered as it includes pictures I took later in the lives of some of the skinheads I’d photographed over 40 years ago. As a photographer you always wonder what happened to those you photograph and what’s always great about doing a new book is that people get in touch that are in the pictures. Yesterday one of the skinhead girls in the book emailed me – she’s now a film director in LA and runs the annual LA Punk Festival. She’s certainly going to be in the second edition.

FK: You’ve said that the skinheads you photographed were happy to be photographed because it made them feel part of something unique. Why do you think they were so open to having their picture taken? How did they see you, and did that change over time?

JI: I guess you’d have to ask those I photographed what they thought of me. I’d be really interested to know- we should have put that in the book ! I was their age and always welcomed, including being invited to take photographs of some of the gang at home, on days out and to accompany them to concerts and the tattooist. It’s been my experience that people who make the choice to be outside the norm are always happy to be photographed if you ask. The worst that has happened to me it that some have said ‘no’ – which is of course fair enough. I think finding people being interested in how you look is an affirmation of the choices you have made.

Spread from Looking For Trouble. I want all you skinheads to get up on your feet by John Ingledew

FK: The skinhead revival, like punk, was a reaction to the social and political situation at the time. Do you see any similarities between the youth movements you photographed in the late '70s and early '80s and today’s youth subcultures? How do you think the way young people express rebellion or identity has changed?

JI: I’ve taught photography at many Art Colleges and Universities and always try to set a project to my students in which they have to photograph the sub cultures and youth movements they are part of. Their results are always wonderful, giving insights into new scenes linked to music and fashion, often well off the radar. The rebellion is of course still out there, I just hope today’s youth will want to share their images in a form I truly love, and I’m not certain they do – a book.