Japanese master Juzo Itami’s 1985 ramen-western marries death, sex, and food together in one large and satiating cinematic broth. The result is a transcendental meditation on the joys of eating.

There’s a special seasoning in the broth of Juzo Itami’s beloved 1985 film Tampopo that elevates it from appetising foodie-film to something transcendental. By no means does the film feature the most mouthwatering sequences put to the screen (in my eyes, that honour belongs to the stomach-rumbling first six minutes of Ang Lee’s Eat, Drink, Man, Woman, 1994), but what it can confidently boast, more than perhaps any other movie, is an understanding of the existential fulfilment that food offers the human experience. The depth and sincerity of the film, though omnipresent, is as sleight as a gunslinger in the Old West, expertly woven into the fabric of the film’s most absurd sensibilities. If one is inclined, it can easily be enjoyed as a feel-good cowboy comedy, a playful ode to the Western genre and its conventions. The premise is certainly simple enough, following two truck-drivers, Gorō (Tsutomu Yamazaki) and his younger sidekick Gun (Ken Watanabe), who happen upon a roadside ramen-ya run by middle-aged widow Tampopo (Nobuko Miyamoto, the real-life wife and muse of Itami). The noodle shop has seen better days: the rent is overdue, the owner is struggling to stay afloat, and the ramen itself isn’t quite up to scratch. Fortunately, Gorō—a character fitting the bill of the type of brooding wayfarer you usually find in a Leone western—volunteers to help teach Tampopo the art of cooking ramen. As they go about their mission, the movie cuts to various unrelated vignettes that explore the role that food plays in our daily lives.

But don’t let Tampopo’s deceptively breezy logline fool you; to travel deeper into its beating heart is to find coded a philosophy that borders on the cosmic. Follow the proclaimed ‘ramen-western’ closely enough and you might discover that everything you need to know about life can be found at the bottom of a delicious bowl of ramen.

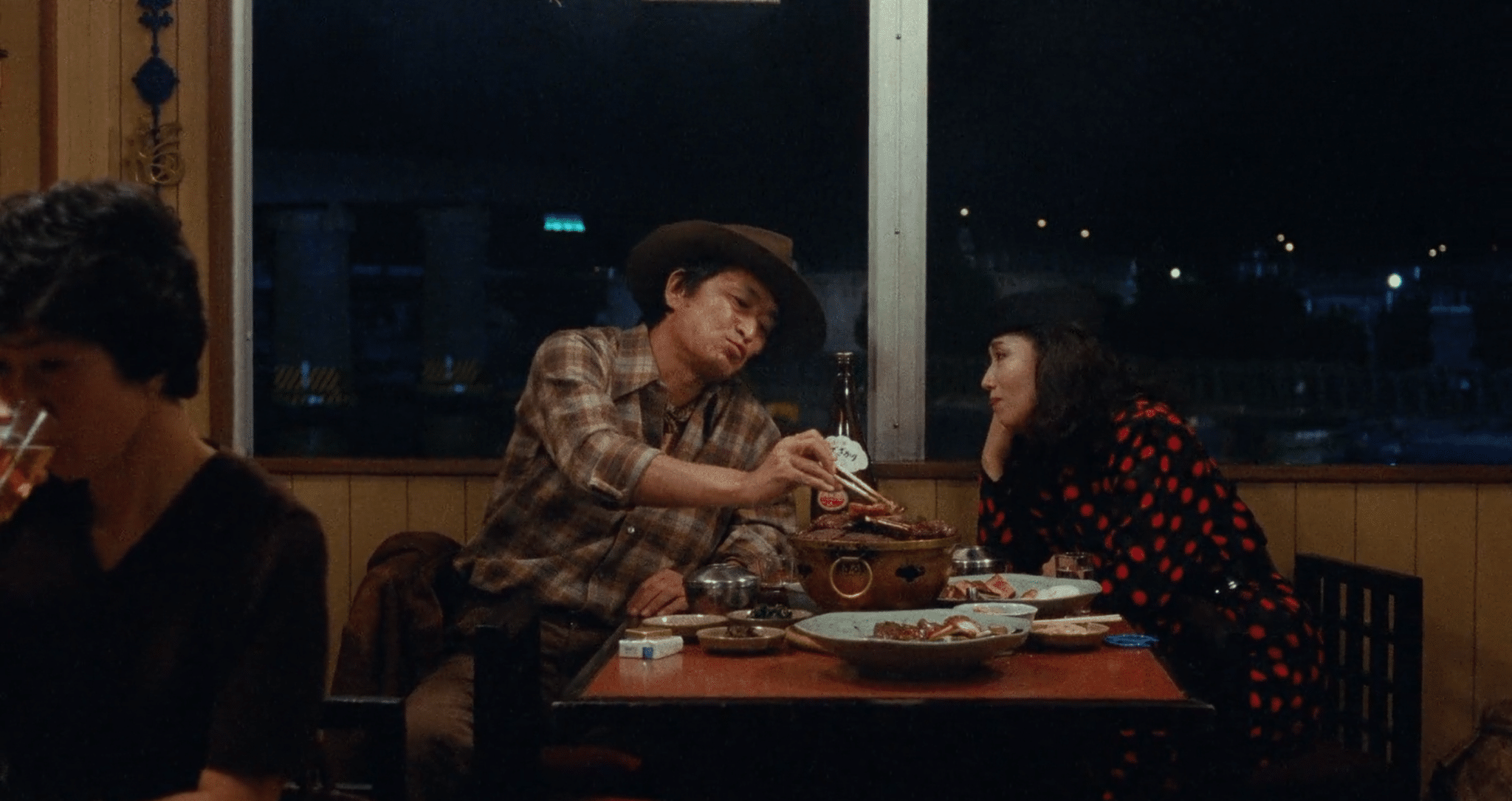

A still from Tampopo (dir. Juzo Itami)

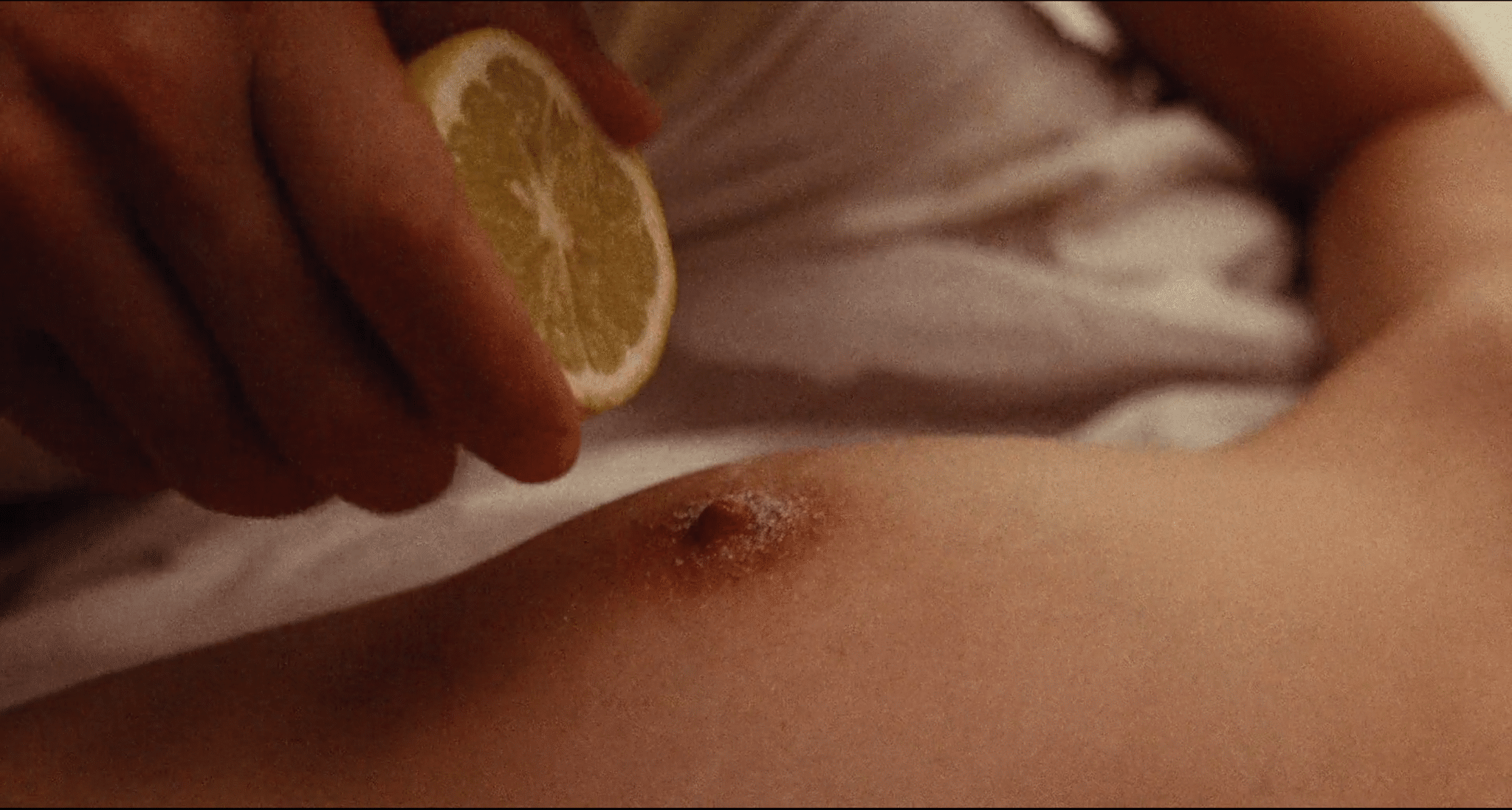

A still from Tampopo (dir. Juzo Itami)

Though Itami pays open homage to the West with loving references to Charlie Chaplin, Luchino Visconti, and the Western genre itself, much of Tampopo’s philosophy is rooted in traditional Japanese values, particularly regarding the contemplation of the external world, and the importance of showing respect even to that which may supposedly be ‘inanimate’. In one of the movie’s iconic sequences, an older man teaches his young apprentice how to eat ramen appreciatively, imbuing the bowl with a spirit unto itself as he describes each step. He relates the significance of expressing affection for the dish, describing its content sensually. “Observe the entire bowl, while savouring the aroma,” he says. “The jewels of fat twinkling on the surface, the menma shoots glistening with fat, the nori darkening with moisture, the scallions floating on top. Above all, the stars of the show: three slices of roast pork, modestly half submerged.”

In part, it’s a clear show of respect to the craftsmen behind the dish, who in the film’s eyes should be honoured and venerated in the same esteem one holds for a great painter or a seasoned swordsmith. But though it might be a stretch to suggest that Itami is directly referencing concepts like tsukumogami (found in Japanese folklore, concerning everyday objects that might acquire a soul, or become inhabited by a kami), there’s a karmic undertone to the scene that feels connected to traditional cultural ideas evoking gratitude to that which serves purpose to the spirit. “The next part is very important,” the master says to his apprentice. “I want you, quietly, to apologise to the pork.” He bows his head, and whispers, “until we meet again.”

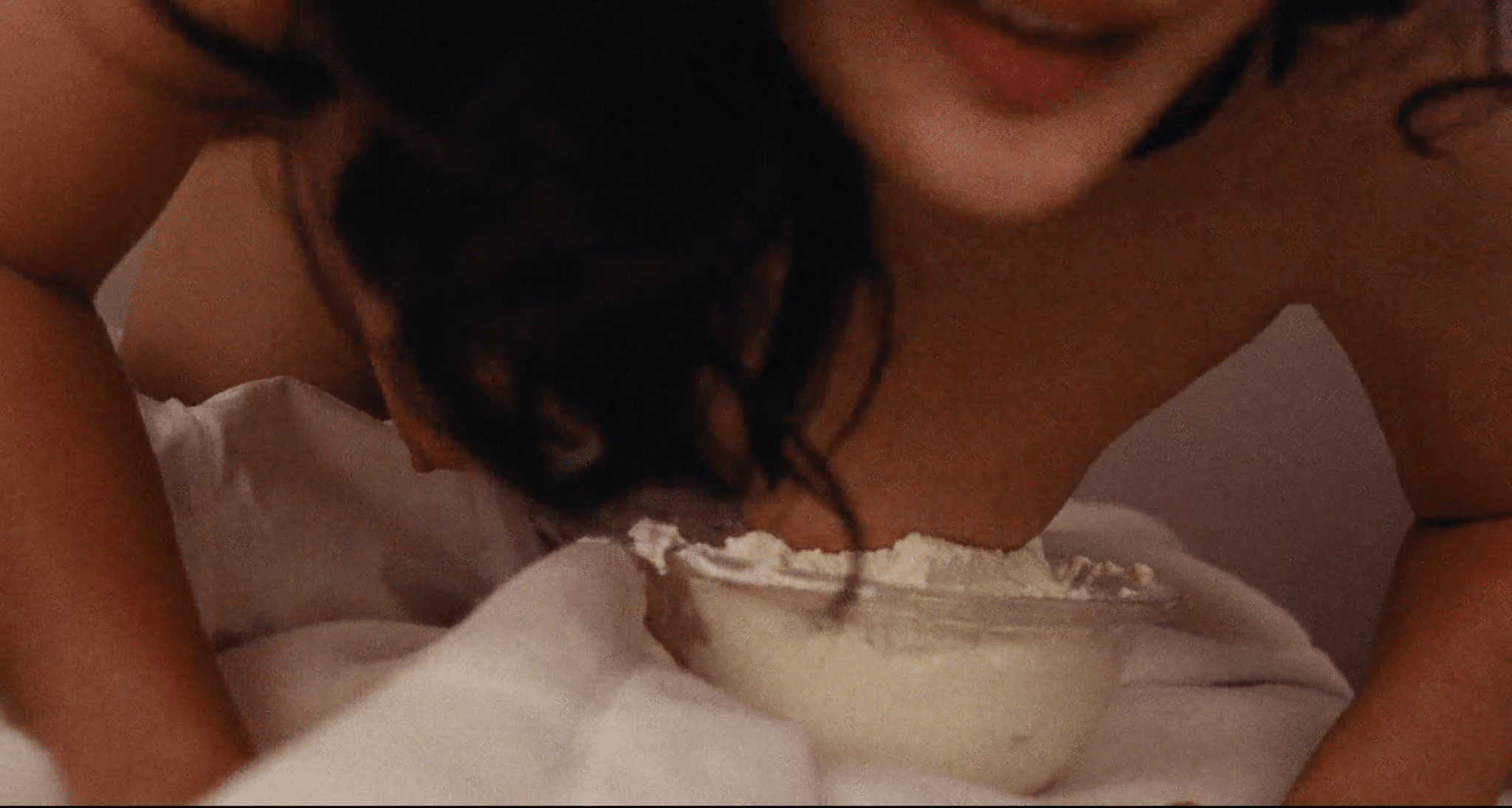

A still from Tampopo (dir. Juzo Itami)

“You’re like something out of a French film. I feel like calling you Jeanne,” says a lovestruck Gorō to Nobuko Miyamoto’s titular character, the secret ingredient that brings Tampopo to life on the screen. It’s hard to talk about the film’s romantic ambitions without first acknowledging Miyamoto, who gives a performance so luminous that it could probably guide a sinking vessel through a hurricane.

Throughout her career, Miyamoto appeared in all 10 of her husband’s feature films, playing everything from a geisha (in Tales of a Golden Geisha, 1990) and a tax investigator (in A Taxing Woman, 1987, and its sequel A Taxing Woman’s Return, 1988) to a “supermarket woman” (in the aptly titled Supermarket Woman, 1996) and a yakuza lawyer (in Minbo, 1992). She is expert at imbuing an everyman quality into her roles, so it’s no surprise that Tampopo remains the feature where she shines brightest, as a working-class widow and mother struggling to keep her late husband’s business alive.

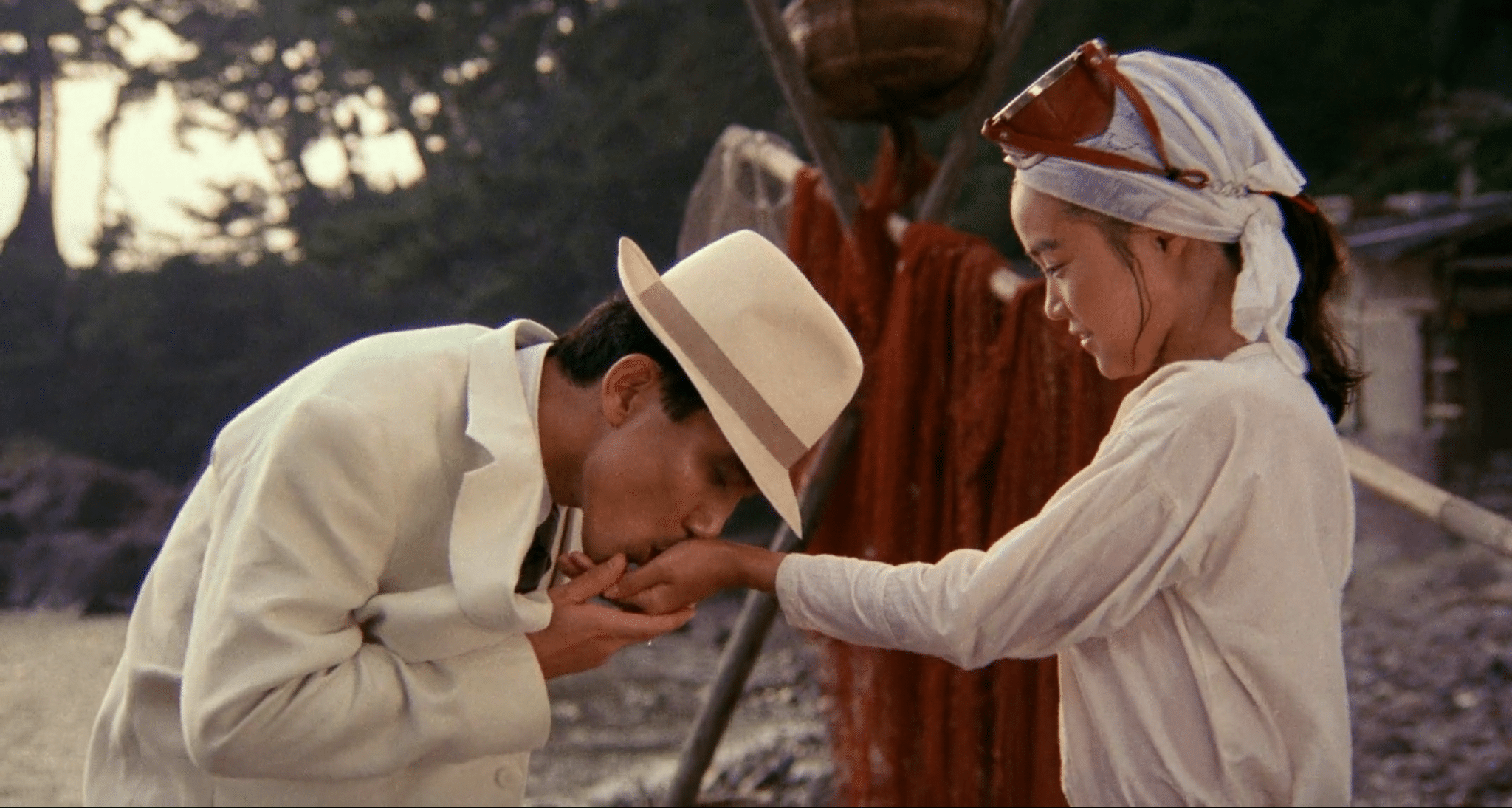

Nobuko Miyamoto in Tampopo (dir. Juzo Itami)

It’s Miyamoto’s performance that brings such a sweet aftertaste to her character’s romance with Gorō, whose tough exterior melts away at the sight of her. Of course, food is at the heart of their love story, ignited when Gorō sees Tampopo, not in a ball gown or dress, but in her chef’s uniform. Their romance is fully realised when the two end up on a date at a barbecue restaurant, bonding as they cook succulent slices of pork belly together. It’s a quiet scene in a relatively erratic movie that exemplifies how Tampopo uses food to boil down the important things in life to something simple, digestible and moving, and at the same time hammers home a universal message that food is at its most joyful when shared with someone else.

The strapline on the poster for the German theatrical release of Tampopo reads “Essen und Sex ist im Grunde dasselbe…TAMPOPO”, which roughly translates to: “Food and Sex are basically the same thing…TAMPOPO”. It’s an amusingly on-the-nose descriptor for a film that encapsulates so much more about its subject than the poster is willing to give it credit for, but it’s not wrong either. For Itami, the art of eating a delicious meal is almost interchangeable with the art of lovemaking, and some of Tampopo’s most memorable sequences concern the interplay of food and the erotic.

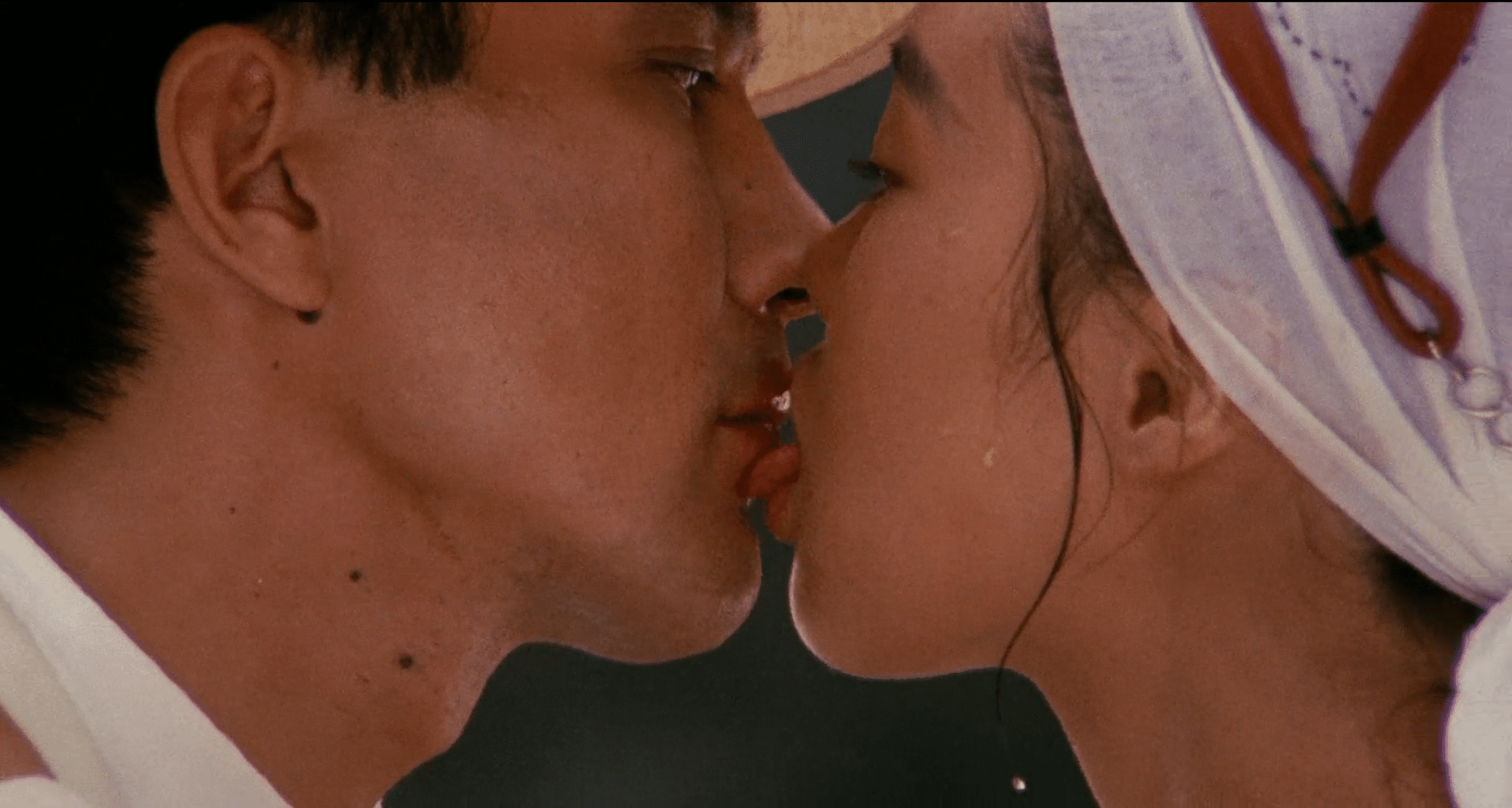

Most famously, one of the film’s vignettes features two lovers engaging in various acts of sitophilia (sexual arousal through food). In the sequence, which bursts at the seams with erotic symbolism, a man in a white suit (who eagle-eyed cinephiles will recognise as Perfect Day’s Kōji Yakusho) squeezes drops of lemon juice over his girlfriend’s nipples. She returns his serve by dipping her breast in a bowl of whipped cream and feeding him, like a mother and her newborn (an image the film crucially references later). He licks honey from the corners of her lips. She laughs as a live shrimp splashes around on top of her belly. Together, they pass an egg yolk between each other’s mouths until it breaks form and the liquid rolls down her chin. Like many of Tampopo’s most strangely touching moments, the sequence deftly treads the line between ludicrousness and honesty, making the case for food as a conduit for sensuality as much as a symbol of community, and that, like sex, it’s truest potential is located in a place liberated from societal constructs and taboos, whether in the kitchen or between the sheets.

Not only does Tampopo put emphasis on the idea that food is unbound by the prejudices of larger society, but Itami takes it a step further, presenting it, first and foremost, as a humble, even working-class craft. In the film, Gorō calls on a mysterious ramen master referred to simply as “Sensei”’ to teach Tampopo how to make the perfect broth. One might first think of a master chef at a luxury Michelin-starred restaurant, but instead, our seasoned grandmaster is a scruffy pensioner living in a commune for the homeless. Despite their place in the gutter of the societal food chain, Sensei and his band of outsiders prove to be Tampopo’s most skilled cooks, almost otherworldly in their understanding of food and its spiritual value. They revere Sensei as a messiah of sorts, and as he readies himself to leave with our protagonists, his disciples join in chorus to sing a tribute to him. It’s telling that the group of chopstick ronins that comes together to help Tampopo is made up of two truck drivers, a lowly pensioner, and a chauffeur, who notably learned how to cook ramen from “the old man at our local stand”. Those who have travelled to Japan will know that the greatest meals the country has to offer are found at the most unassuming of establishments, and with Tampopo, it feels overwhelming at times, as if Itami is tipping his hat to the true heroes of the culinary world.

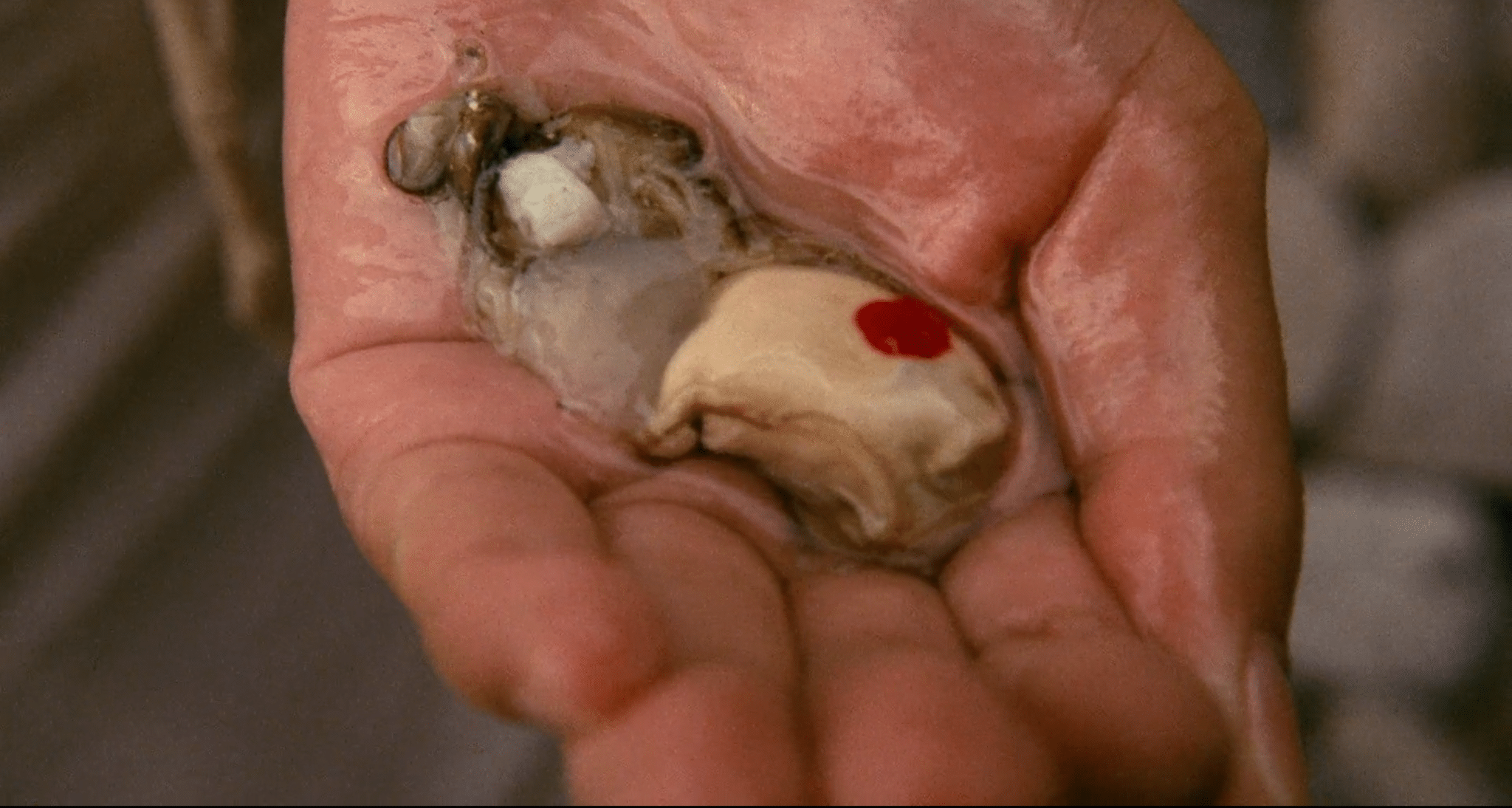

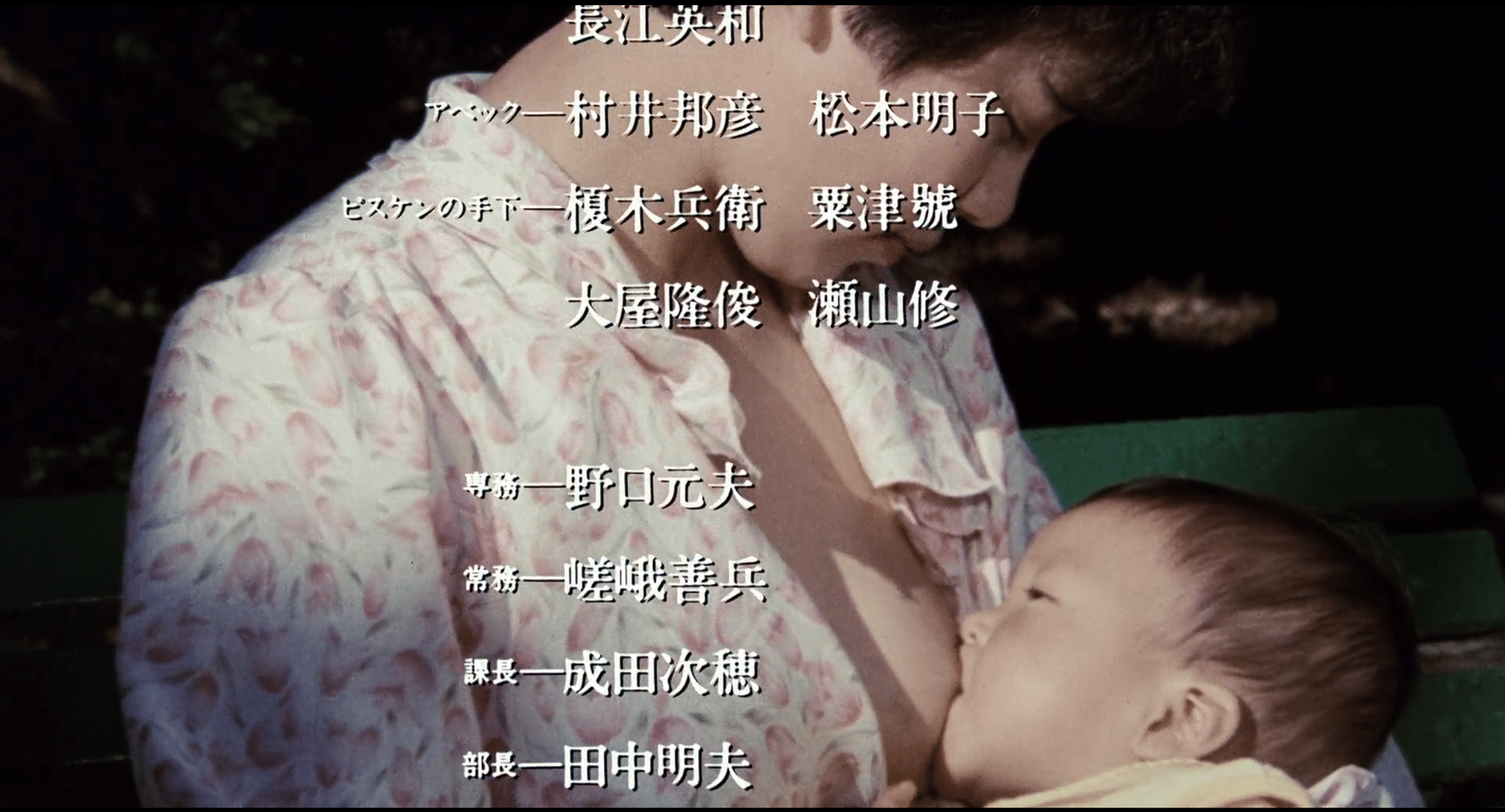

Above all, there’s something innately intimate about Tampopo’s communication of food, as though Itami believes that the act of eating is the cosmic centre of all human experience—that food exists not just for sustenance, but also as unquestionable proof that we have souls. Pulses of life and death run through the film—reminders of our mortality. In one sequence, a young pearl diver erotically licks blood off Kōji Yakusho’s mouth after he cuts his lips on an oyster shell. She offers to let him eat it out of her hands, an act that awakens something, sexually and spiritually, in both of them, and we see in her a moment of instant coming-of-age. In another, a housewife, quite literally dying from exhaustion, is brought back to life by an unshakeable sense of duty to cook a final meal for her family, dropping dead on the spot the exact moment they take their first bites. Time and time again, Itami brings us closer to our own humble nature—our fickleness, our yearning, our values—by expressing gratitude for the joy of eating. The film’s final shot, playing as the credits roll, brings this quietly sprawling ethos full circle, tracing every moment that came before it to one glorious source, with the camera zooming slowly on the simple image of a baby suckling on the breast of its mother.

The closing credits to Tampopo (dir. Juzo Itami)