Super producer Alex Saks talks bringing It Ends With Us from page to screen, and the movies that shaped her artistic sensibilities.

Producer Alex Saks can do it all. She’s played with some of the greats of contemporary independent cinema like Sean Baker (on The Florida Projectand Red Rocket), flitted between low budget festival hits and big-star blockbuster vehicles (Thoroughbreds and No Hard Feelings, respectively), and has steadily become one of the most in demand producing talents in town. With the release of It the Blake Lively-fronted Ends With Us, director and star Justin Baldoni’s adaptation of Colleen Hoover’s romance novel—which has to date sold millions upon millions of copies and risen to number one on the New York Times Best Seller List twice—Saks is showing us exactly why she’s the hottest producer in Hollywood.

Saks joined us to discuss the films that influenced her artistic sensibilities, Ryan Reynolds involvement in the production of It Ends With Us, and her experience bringing a modern phenomenon from page to screen.

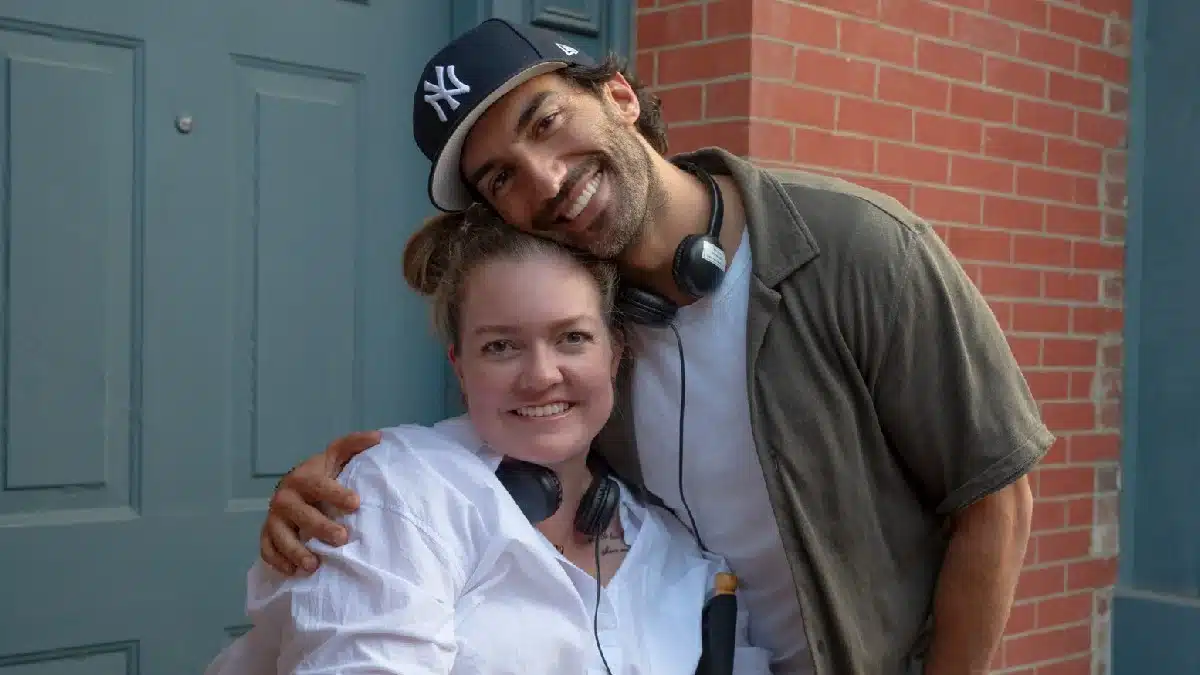

ALEX SAKS (PHOTO BY ALYSSA ARMSTRONG)

Luke Georgiades: Though you clearly had the fans in mind when you were making this, I would argue it’s as much for non-fans, and the reason I say that is because I was one of those people who wasn’t familiar with the book and as a result I was completely affected by the turning point halfway through the film.

Alex Saks: To your point, that’s exactly what we were trying to do the entire time. From the script to the direction, we were trying to balance appeasing the fans who love this book and these characters, but also surprise them, and furthermore, for the people who didn’t have context…we wanted to take them on a ride. By that I mean we wanted them to feel the way that Lilly would actually feel every step of her journey through this narrative.

We don’t make a ton of movies anymore that elicit emotions quite like this. I miss that as an audience member. Colleen gave us such a beautiful blueprint, and Justin was very clear about how he wanted to portray the domestic violence scenes—in a way that wasn’t necessarily clear. Because he wanted to show us that the reality of Lilly’s situation and her response to her situation is unclear and muddy.

LG: Justin handles these themes with so much sensitivity. What qualities did he bring to this production that showed he was the right person to bring this story from page to screen?

AS: There was a painstaking amount of thought and consideration and consultation from our female screenwriter Christie Hall, and Colleen, Blake and myself. This whole movie was a collaboration in the truest sense of the word. Coincidentally, I had taken a general meeting with Justin in 2019 because I had watched his TedTalk, which predates the book he has since written about toxic masculinity, and I was taken by this speech he gave. It was at the end of that meeting that he told me he was about to get the rights to this incredible book, and asked if I wanted to check it out. So I read the book three years before actually coming onto the project, after I made No Hard Feelings with Sony, who were co-funding this film. They brought me up as a potential producer to Justin, and he immediately said “oh my god, she’s the first person I ever sent this book to.” There’s no clear answer to your question for me because my entire experience with Justin has felt so deeply interwoven with the themes of the book and the project itself. Him telling this story always made sense to me because of that.

COLLEEN HOOVER AND JUSTIN BALDONI ON SET OF IT ENDS WITH US (2024).

LG: How did you, Colleen and Justin try to surprise people who already had a relationship with the story?

AS: Colleen was very involved. I’ve never worked on a project where every department and individual involved were so consistently asking each other “what would the fans think of this?” We would call Colleen often and ask her if a tiny change we made to her original story made emotional and narrative sense to her, or if she imagined that Lilly Bloom would look the way she did. Staying true to the story was always on our minds.

LG: What was it like at the premiere to finally see the finished film with a fresh audience?

AS: It felt especially great because there were so many stops and starts due to the writer’s strike. We originally had an earlier release date which later became impossible to hit because we were shut down for six months. What was interesting about that shutdown is that I had never gotten a chance to make two-thirds of a movie, then gotten to take a nice long creative break, look at all the footage you have, and actually have the time and benefit of recrafting anything that isn’t working. We got to see a stringout of the movie before the movie existed.

LG: The hardest character to nail here was probably Ryle, because we’re not used to seeing abuse portrayed like this on screen. I wonder how much that character changed from the script up until the end of the production.

AS: It really didn’t. Directing and starring in a movie is exceptionally challenging, but one of the things Justin had on lock was how he was going to portray this character. I don’t want to know what it was like inside of his brain during that time, because it was a lot of pressure and stress, but the fact that he had this anchor of how he was going to play Ryle so early on, really helped. It remained consistent throughout the whole shoot.

LG: What do you feel like this movie is trying to communicate about the nature of abuse that many audience members would never have considered before?

AS: What it’s actually trying to say is something about survivors, and the fact that you can change your circumstances at any point. This is a movie about female empowerment at its core, and what happens to her doesn’t ultimately and shouldn’t define who she is. The movie serves as a reminder for those who are in similar situations, or who have loved ones in this situation, that no matter how bad it gets, that hopefully you have the power to end the cycle. Ultimately, it’s meant to be hopeful.

LG: I think Blake brings that character to life beautifully.

AS: Part of the reason I was assigned to the movie was because it needed to be made on an accelerated timeline, and I had already done that for Sony and No Hard Feelings, so with that in mind, casting Blake was one of the first things we did. She was the first person I went out to as a part of the team. I was thrilled, and I remember calling Justin being so excited, because aside from the fact that she’s a phenomenal actress, I knew how much else she would bring to the project, from her aesthetic eye, to her humour and nuance. When I came on, Justin was very clear that he wanted to make an elevated movie, and Blake’s sensibilities lends herself to that

LG: Recently Blake mentioned that Ryan Reynolds works on every project she takes and vice versa. Can you tell me about what that might entail?

AS: Blake was being honest when she said “no one knows this except for you now” to the reporter. Maybe, deep down, we all thought that maybe that was happening. But a lot of it was coming from Blake. There was so much at every level from the script, to the production design to the costumes that she was involved in as a producer. So it was both a surprise and not a surprise to get that confirmation that it was two of them in some cases. There were things that we’d see on monitor that were such delightful surprises despite being departures from the page, and in my experience in the feature world, that happens, and sometimes those kinds of happy accidents happen on set. They can make the movie better.

LG: The original book of course has a very popular sequel. Did you design the film as one of two?

AS: We decided to make it purely as an adaptation of the first book, so we haven’t started talking about what a sequel could look like yet.

LG: You’ve mentioned before that your two biggest film inspirations are When Harry Met Sally and Fellini’s 8 ½. Not to put you on the spot, because you gave that quote literally 8 years ago, but I’m interested to know how those two films changed the way you think about filmmaking?

AS: I would give the same answer today! Look, I have so many favourite movies. It’s an impossible question to answer, but I like to cheat by giving two answers that are vastly different movies, but both have similarities you might not expect. When Harry Met Sally is one of the first movies that I endlessly rewatched—marvelled at the character work, and the comedy and the heart of it. For me, if I ever get anywhere close to making a movie of that quality, I will have succeeded. Nothing else matters. It’s getting to tell a story the way Nora Ephron and Rob Reiner is that is so excellent on every technical level, every performance level, any craft level, that by the way, reaches super filmmaker-driven cinephiles, and a wild mainstream audience. To me, when cinema can reach both of those, that’s when it’s at its best. And then, 8 ½ indulges the side of me that has been most of my career up until the past couple of years, which is making auteur-driven independent cinema. I was an Italian minor in college, and my mom’s Italian, and I saw that movie in college and it changed me as a person, and it changed what I thought cinema could do. It was so introspective. I wrote a 20-page paper in college, in Italian, about the mirror construction in the movie—which, by the way, is an endlessly challenging piece, and I don’t think it’s very good. It’s not publishable, is the sad truth [laughs]. It made me fall in love with filmmaking all over again.

I get asked often why I make the movies I make, and if I look at all the movies I’ve made over the past 8 years, and there’s 20+ of them, if you track when I took the movie on, each is a perfect reflection of where I was emotionally in that moment in time. For me, the personal story element of filmmaking is what I learned from 8 ½.