With The Substance, Coralie Fargeat deftly refigures the cinematic trope of the doppelgänger in order to delineate the most extreme conclusion of women’s self-hatred under capitalist patriarchy, says Laura Grace Simpkins.

The Substance (2024) is the hotly anticipated second feature film from writer-director Coralie Fargeat. It stars Demi Moore as Elisabeth “that old bitch” Sparkle, a former A-lister turned TV aerobics star. Fired from her job on her fiftieth birthday and the victim of a car crash the same unfortunate day, Elizabeth is covertly informed that she would be the perfect candidate for a black market drug which can unleash a better—younger, barely leotarded, hyper-sexualised—version of herself, whom she calls Sue (Margaret Qualley). The plot follows the battle for control between the two versions of the self.

The well-advertised grossness of the trailer is delivered. There’s blood and guts, births out of backs, and intestines tumbling in slow motion from undone zips. What I found most intriguing about The Substance, however, wasn’t the gory theatrics, which reach a slightly ridiculous apex in the didactically named “Elizasue Monster” third act. Instead, it is how Fargeat interrogates the notion of female self-hatred: what it looks like to fully despise yourself. The film’s greatest achievement is how it holds a mirror up to our self relationships during an especially self-loathing era of human history. Like Elisabeth, we do not always like the reflection we see.

With Sue, The Substance literalises the better version of the self that those of us raised as women carry around in our heads. The one we attempt to ascertain via make-up, fashion, beauty products, facials, fillers, plastic surgery, exercise regimes, diets, filters, and photo editing apps, to name a few. By conceptualising a novel, but not unimaginable technology, Fargeat deftly refigures the cinematic trope of the doppelgänger in order to delineate the most extreme conclusion of women’s self-hatred under the capitalist patriarchy.

THE SUBSTANCE. IMAGE COURTESY MUBI.

The doppelgänger is, of course, most notably written about by the father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud in his essay “The Uncanny”. Freud explains that the doppelgänger is initially viewed with the unbounded self-love, or “primary narcissism”, that children have for themselves as they notice their doubles in mirrors and shadows. But, when childhood is left behind, the doppelgänger takes on a different aspect. Doubles we confront as adults remind us of the repressed self-love that we felt for ourselves when we were younger and become the “ghostly harbinger of death”.

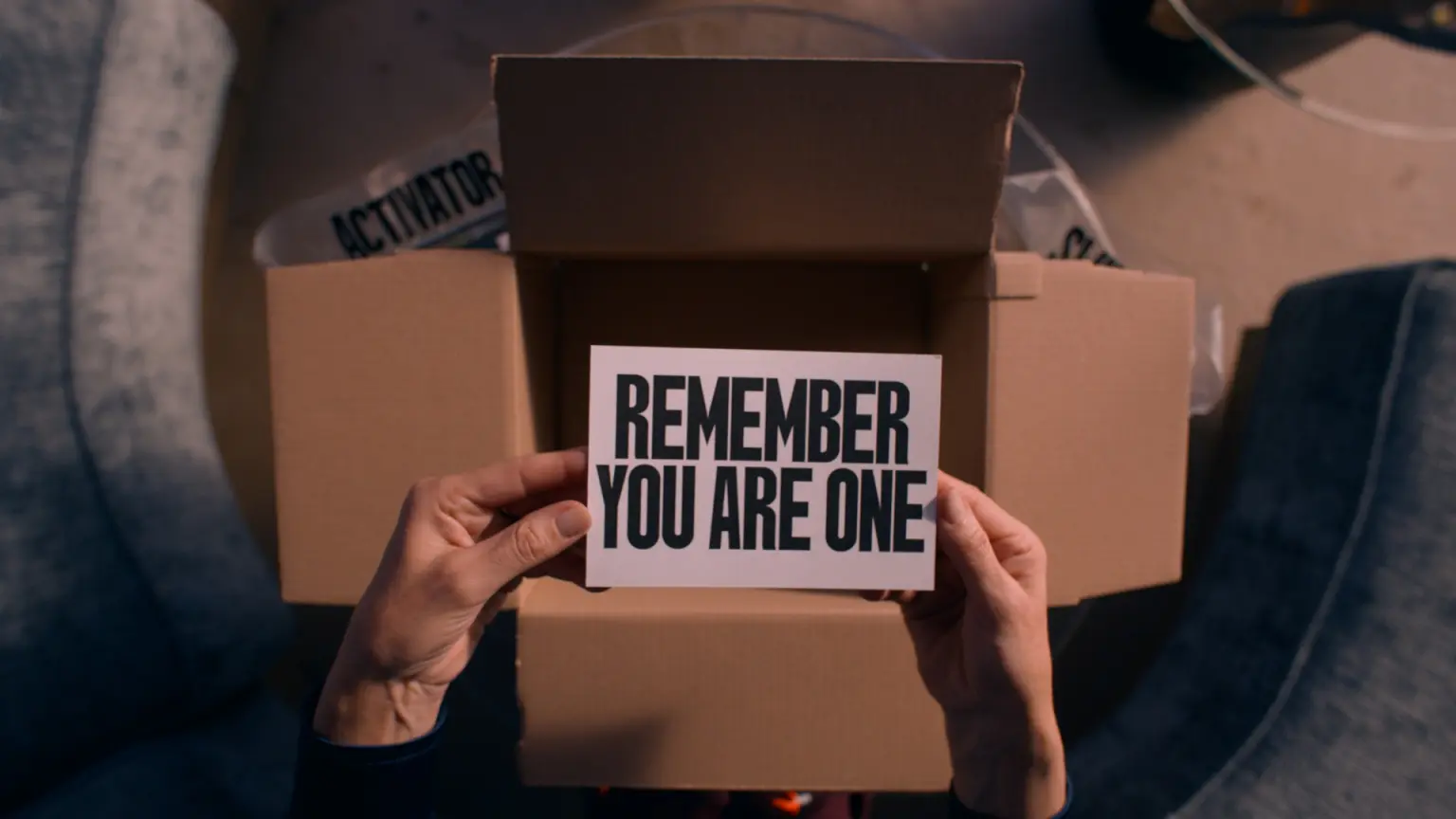

The post-childhood doppelgänger that Freud identifies, which I thought particularly apropos to thinking about The Substance, represents our consciousness’ capacity for self-criticism, for splitting ourselves in two. Frustrated with having to switch places with Elisabeth every seven days (a non-negotiable of Substance usage), Sue resolves to stay awake for hours longer than she should. When she finally relinquishes her consciousness to Elisabeth, Elisabeth finds that one of her fingers has aged. Determined to report the “misuse”, Elisabeth phones the helpline, where she continually refers to Sue in the third person, as “she”. The monotone bot on the other end goads her: “Remember, you are one”. As viewers, we forget this too, with the contrast between the vivacious, high-kicking Sue and Elisabeth, as she hunches over her hoovering in a dressing gown that only gets greyer with every passing scene, reinforcing our belief in their divide. But Sue is not an allegory of youth and selfishness. She is the critical doppelgänger of Freud’s sprung to life. And that is why she’s so frightening to Elisabeth: she is a part of her that she recognises. She’s the part of her that wanted to order the Substance in the first place.

As I watched, I wondered if there would be a way out of using the Substance in the logic of the film. There is. After three months of existing without swapping, Sue is forced to change places with Elisabeth to stabilise her body. When Elisabeth resurfaces, she discovers that she has physically deteriorated to a point of no return. A termination kit is ordered. Elisabeth tries to kill Sue with a tarry black serum, but reneges, leaving an inch or so left in the syringe, explaining as much to herself as to Sue: “I can’t do it. Cos I need you.” Elisabeth needs Sue, because even though she hates her, she hates herself more. The botched abortion leads to a severing of the two selves. Sue wakes up.

THE SUBSTANCE. IMAGE COURTESY MUBI.

The central paradox of the doppelgänger motif in cinema poses the impossibility of encountering yourself as another: not as a reflection or shadows or anything which passes a vague resemblance to your appearance, but what it would be like to truly meet yourself. When the doppelgängers of The Substance behold each other, they know they cannot both exist for long, because they depend on the other’s body: Elisabeth on Sue to stay young; Sue on Elisabeth to stay alive. Full of rage at Elisabeth’s betrayal, Sue launches into an attack. Like in her freshman film, Revenge (2017), Fargeat unflinchingly shows us every detail of the violence, lingering for minutes after most directors would cut away. Strangling Elisabeth against a promotion shot from her TV aerobics days (the film’s stark mise-en-scène is peopled with images of Elisabeth or Sue in mirrors, posters, billboards, adverts, and TV screens), Sue then chases her into the bathroom, a white-tiled Parthenon of self-hatred, where she proceeds to smash her head in against the sink. We hear every sickening crack and crunch in ASMR high-definition. Elisabeth manages to escape, dragging herself into the condominium’s open-plan living space, but she’s cornered by Elisabeth, and beaten to a raw pulp on the plush pink carpet.

“Sue is not an allegory of youth and selfishness. She is the critical doppelgänger of Freud’s sprung to life. And that is why she’s so frightening to Elisabeth: she is a part of her that she recognises. She’s the part of her that wanted to order the Substance in the first place.”

As Elisabeth dies, Sue takes stock of what she’s done. A single line of tears reminds us of the flesh underneath her blood-soaked face. She chokes on sobs that don’t come. She looks stunned. This is one of the most interesting moments of The Substance. Here Fargeat manages to capture the childish tenderness we still have for the parts of ourselves we hate the most. The self-love or primary narcissism is there, deep down. Or maybe Sue is just realising that she needs Elisabeth, not because she loves her, but because she loves herself more.

In his analysis of the doppelgänger, Freud didn’t find it necessary to locate how wider society influences how the critical self is formed. To him, self-criticism was a natural stage in the evolution of the ego as we grow up—perhaps because in 1919, the year “The Uncanny” was written, the beauty industry barely existed. Today, Freud’s idea seems outlandishly naive. At the end of the film, a decomposing Sue injects the original activator serum into her thigh, desperate to “create a better version” of herself yet again. This releases the “Elizasue Monster”, mentioned above: a roving mass of teratomas in a Cinderella dress. Would The Substance be a stronger film with a subtler ending? Possibly. But what is most effective about it is the recognition that many female and gender-marginalised viewers will have for Elisabeth’s, and then Sue’s, obsession to become the doppelgänger of their critical selves—whatever it takes.