At his farmhouse in Herefordshire, A Rabbit’s Foot met the legendary director Bruce Robinson to discuss his career, his brilliant and evocative writing, and why he replaced Hollywood for the English countryside.

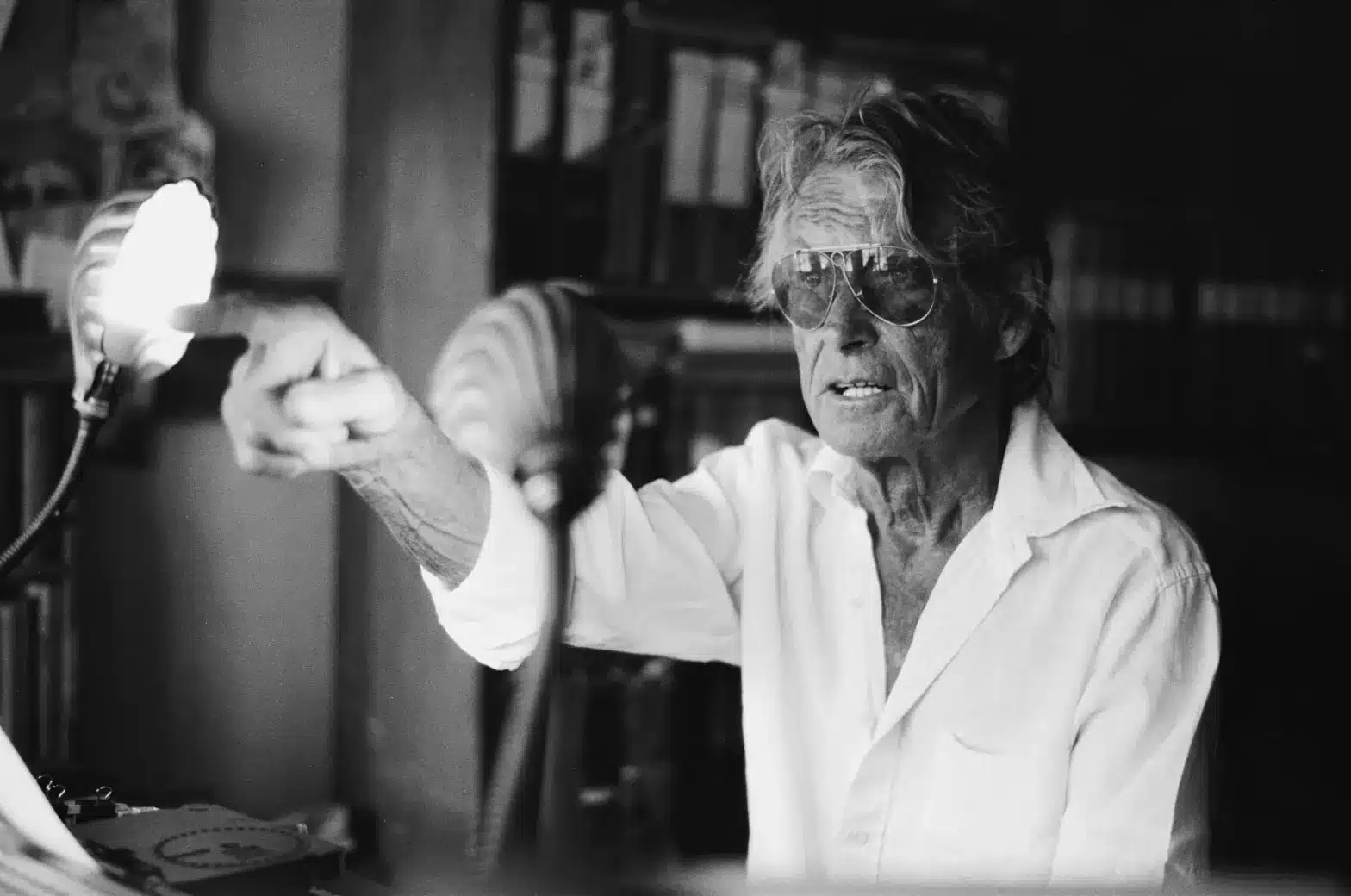

Bruce Robinson’s Herefordshire farmhouse cannot be found on Google Maps. On our first attempt, my photographer Laurie Hills and I were led to a different site. “This can’t be it,” we said to each other, observing the nondescript newbuild, the gunmetal Audi SUV, and the disturbingly cordial hens. We had some preconceptions about Robinson— the writer/director famous for the cult comedy Withnail and I (1987)—and none of those things added up to them. “I’m expecting a bit more rock ‘n’ roll,” my companion said. We had watched a documentary where Robinson was racing his Aston Martin up and down country lanes, wearing a leather jacket and aviator specs. “Where’s the Aston Martin?”

Wrong farm. “You’re lucky I know how to get to your destination. People always make that mistake and come here,” the owner tells us. Robinson’s farm was more of the scene we had pictured. Stones and thatched roofs, vibrant flowers and large barns. He also calls hens “cluckers”. But no Aston Martin. “My wife [the artist Sophie Windham] sold the DB4,” the 77-year-old says when we ask about it. “I’m not really into possessions.”

BRUCE ROBINSON. © LAURENCE HILLS

Robinson offers us a can of Guinness each but takes an alcohol-free version for himself. He isn’t drinking. “Not yet,” he explains. “I’ll start again when I write.” When he gets back to it, he says, it’s a bottle of good red wine by the typewriter (he uses a beautiful and expensive IBM that makes a satisfying clack at each tap of a letter). Drinking allows him to go “over the speed limit” as he puts it. “People don’t drink and drive because they have to stick to the limit. But when you’re writing, you want to go up to 70 mph. That’s where the madness happens.”

“Shall we do the interview by the pool?” The pool area is the only part of Robinson’s farm that seems removed from the rustic Herefordshire countryside—a bit like a suburban commuter belt among the romantic stone-tiled and flower-coated cottages. “When my family and I left Los Angeles to live here, our daughter asked where the pool was,” he explains. “So we had one built.” A few weeks earlier, his daughter had her wedding party by the same pool.

Even though he directed one of the quintessential London films, he doesn’t return to the capital much, but when he asks “how things are” in London, it is spoken with a mischievous knowingness; a throwback to when he was a handsome chancer in squalid flats and then a successful filmmaker and writer frequenting Soho’s Groucho Club. Robinson lived in London from the 1960s to the 80s before moving to Los Angeles to direct Jennifer 8(1992). “It’s not my version of the city now, though. Everyone I know has fucked off and the restaurants I like are shut. It’s lost its quaintness. It’s too ordered.”

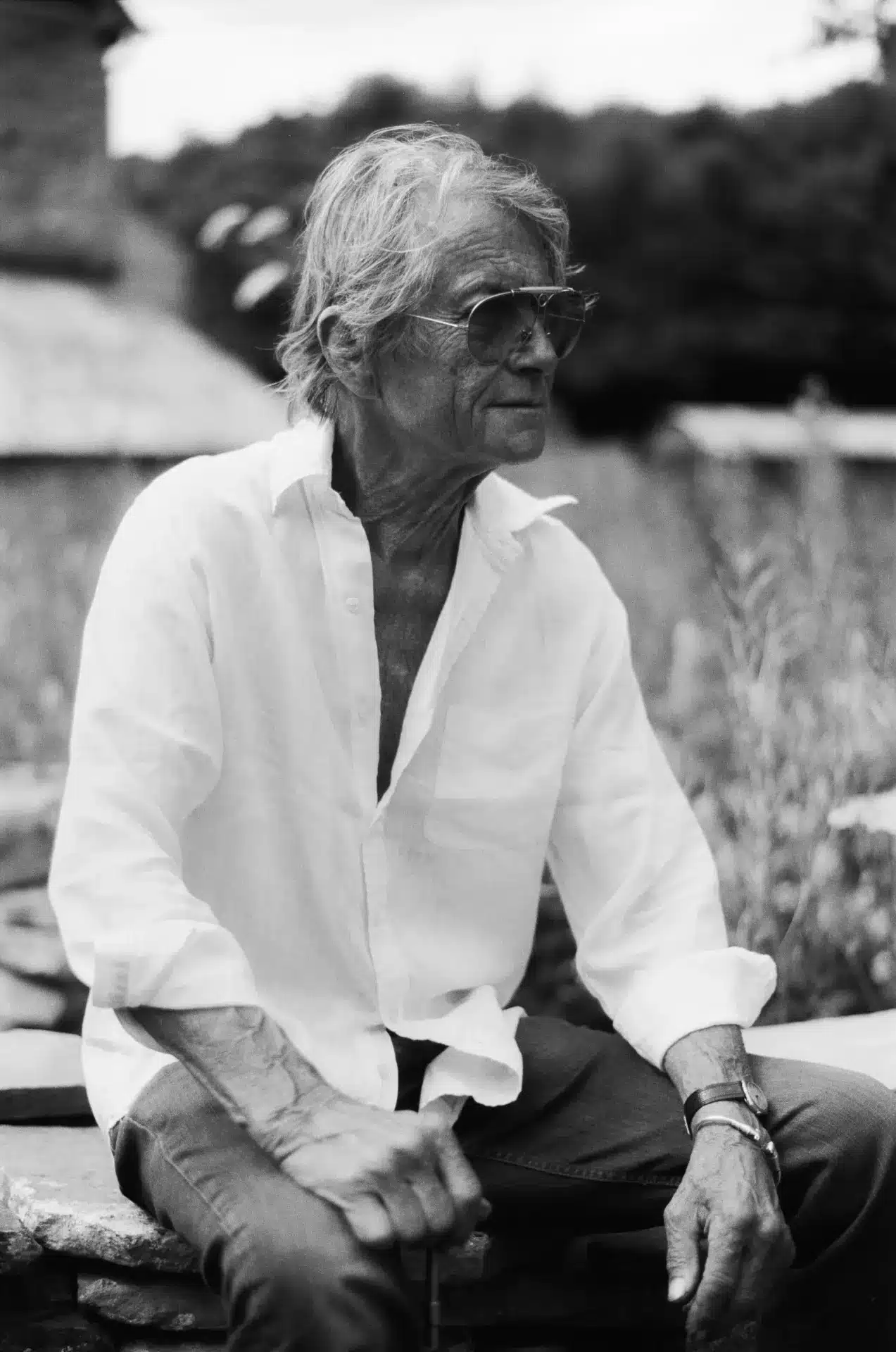

BRUCE ROBINSON. © LAURENCE HILLS

Withnail and I was inspired by his own boozy misadventures in Camden Town. “It was a real rundown shithouse of an area,” he says. The apartment was nicknamed the Skin House Hotel [‘skin’ is Liverpudlian slang for friend]. During the 1960s, Robinson lived there with a number of friends including Vivian MacKerrell, the mythologised inspiration for Withnail, a character that has been adored and quoted since the film’s release. “Incrementally everyone stopped living there except for me and Viv. We were the last survivors in Albert Street. And he fucked off and got a job, even though he couldn’t act to save his life. And then I was alone there. That moment alone is in the original script. This awful tangerine street light is pouring over the floorboards. I thought I might as well have a good fucking self-indulgent weep. It was absurd.”

Last month, Robinson revisited Withnail and I for a theatre production in Birmingham. It was supposed to follow the Withnail story after 30 years. “It was tricky and the theatre people had good intentions,” he says. The earliest version began with Uncle Monty’s funeral. The “I” character [or Marwood] attends and spots Withnail lurking at the back. This is the story so many fans of the cult film have been waiting for, but “I cannot go there,” Robinson says. “Not only is Viv very dead but Withnail is dead too. In the ending of the original script, the character blows his head off. And there is no life after death as far as I am concerned.” Robinson agreed to adapt the original script to the stage instead, but his ownership of the story was still tested. He is famously “fascististic” (as he puts it) about how his lines should be read: no improvisation, no artsy approaches to the dialogue. “You have to stress it right, and therein lies the comedy. So I’m sitting in the theatre,” he says, putting his head in his palms, “watching these very good actors, knowing that they’re misreading things. God, my toes were digging into the fucking ground.”

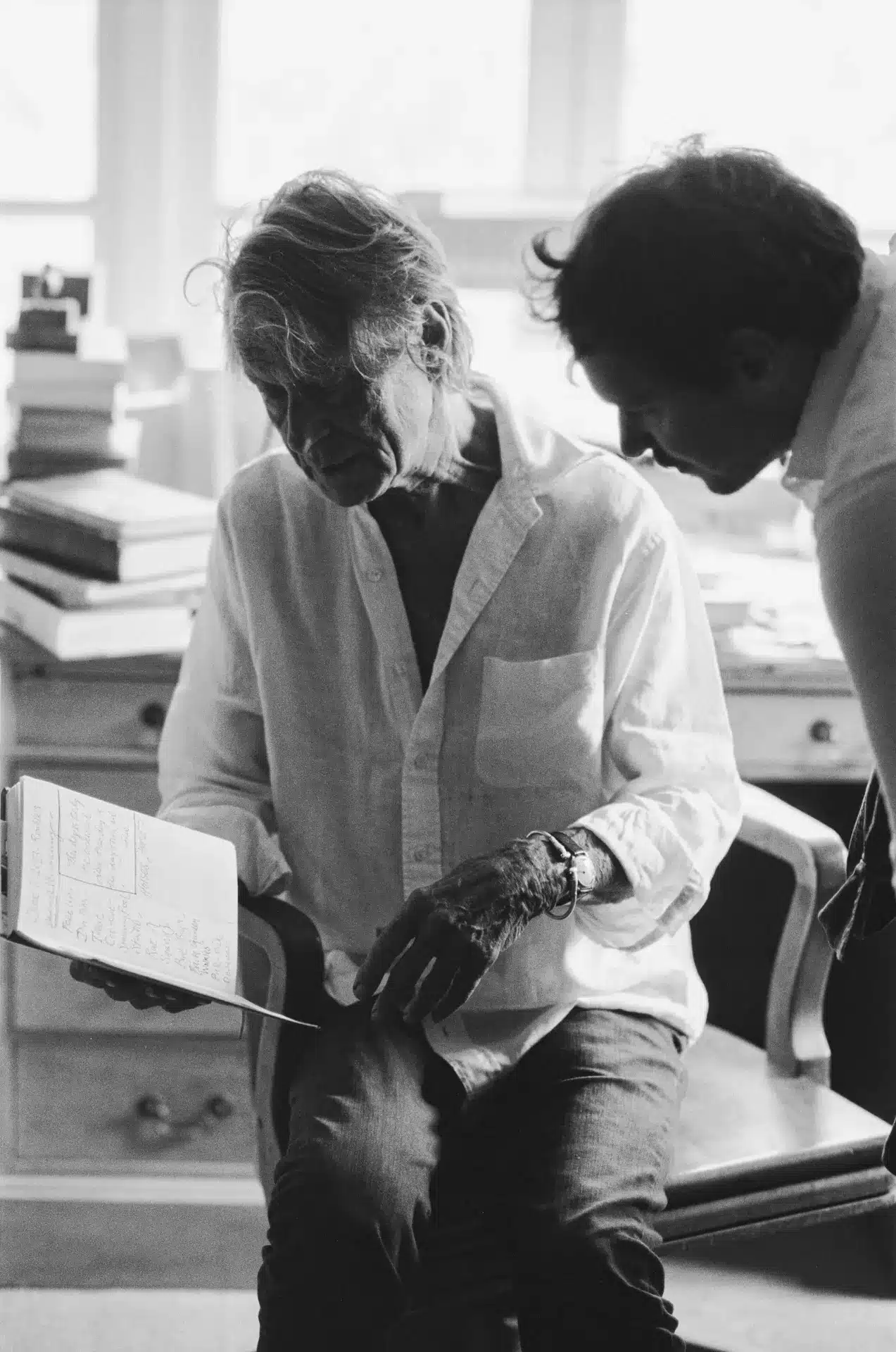

BRUCE ROBINSON AND CHRIS COTONOU © LAURENCE HILLS

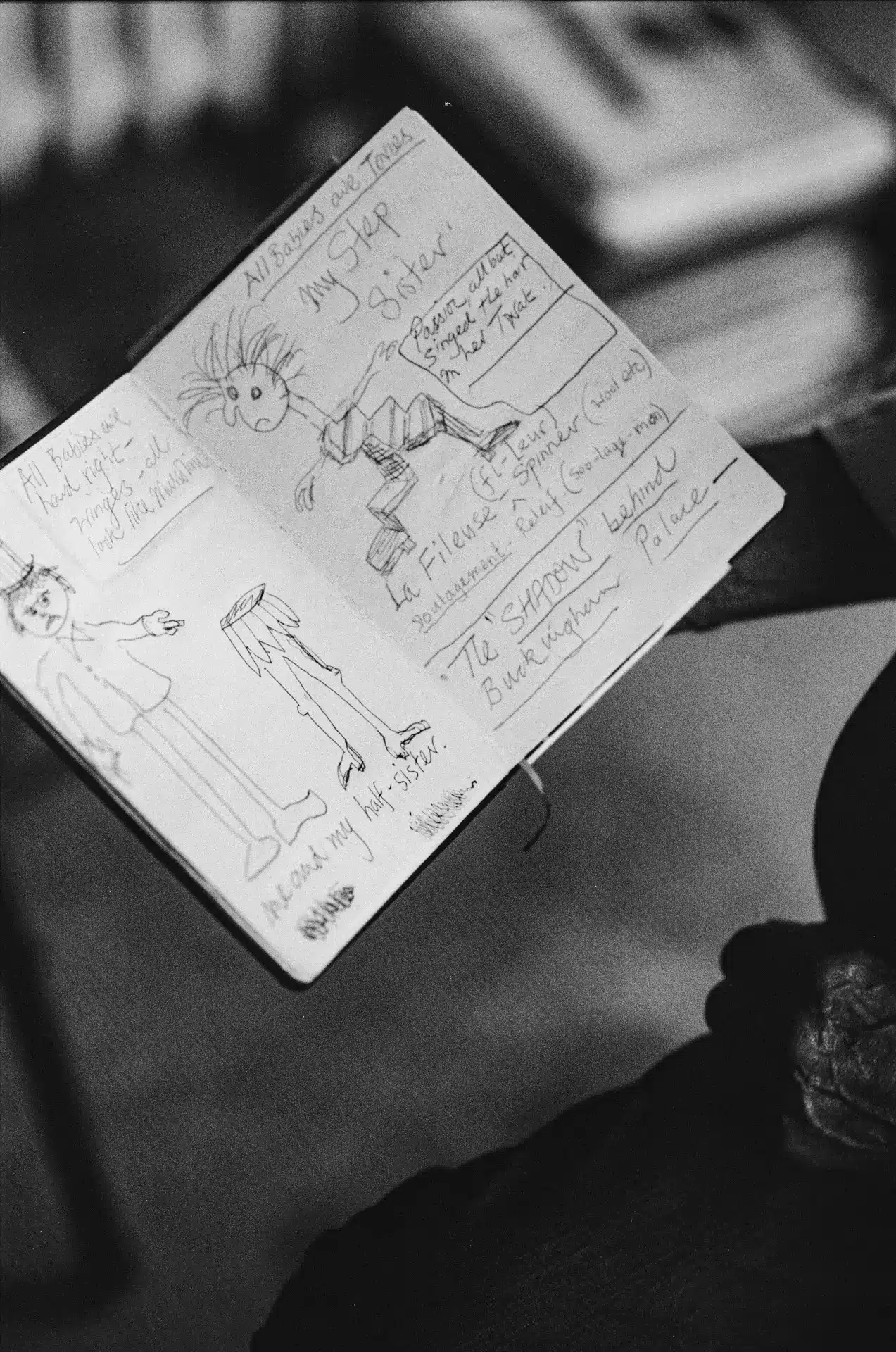

© LAURENCE HILLS

Robinson wrote Withnail and I partly as an escape from the trauma of working for the Italian director Franco Zeffirelli on Romeo and Juliet(1968). Before being a writer and director, he had originally planned a career as an actor. In Zeffirelli’s film, a young—and frankly beautiful—Robinson played the part of the angelic Benvolio. “That was a horrible experience. Zeffirelli crossed a line.” He says the director, who died at 96 years old in 2019, was sadistic in his sexual harassment and ruined Robinson’s desire to continue as an actor. In one story, Zeffirelli molested the 22-year-old Robinson after the latter had taken a shower, offering to dry his hair and then forcing himself on the young actor. There were more episodes, but Robinson prefers not to go into too much detail. “When I left the set, I tried to be the bigger person and shake his hand,” he tells me. “Zeffirelli grabbed me by the balls and exclaimed ‘All I shake are cocks’.”

“I grew up with a sense of injustice… I can be vociferous about what I perceive as unfairness in society, and evil fuckers laughing in our face. Anger is a motivation for me as a writer.”

Bruce Robinson

After leaving drama school in 1967, he couldn’t wait to go out to Rome to work for Zeffirelli, who was hot off the success of an adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew, starring Richard Burton. It promised to be an important step in young Robinson’s career. “But night one, and he had his rubber gloves off. My anxiety levels increased all the time and when the film ended, I returned home and had a nervous breakdown that led me into Ramsgate hospital.” The lecherous character of Uncle Monty in Withnail and I was based on the director. “I had a lot of trouble,” he reflects.“Many people had problems after working with Zeffirelli.” Apart from a few choice roles over the years, including a lead role in Francois Truffaut’s bleak The Story of Adèle H (1975), the experience encouraged the actor to start writing instead.

PAUL MCGANN AND RICHARD E GRANT IN WITHNAIL AND I (1987). BY BRUCE ROBINSON.

Richard E Grant, who played Withnail, described a Bruce Robinson character as “one man against the world” and I ask if his early traumas influenced the characters and stories he would later tell as a writer. Robinson had already suffered brutal abuse at the hands of his stepfather as a child. He had never met his real father and was raised by his mother and her husband in Broadstairs, a coastal town in Kent. “I grew up with a sense of injustice,” he admits. “I can be vociferous about what I perceive as unfairness in society, and evil fuckers laughing in our face. Anger is a motivation for me as a writer.”

He gets suddenly aggrieved and starts raving on the state of our country and the filth and corruption of politicians and the major water companies. A Bruce Robinson rant is legendary. It was the biggest criticism of the dialogue in his second comedy, How to Get Ahead in Advertising (1989), which follows an advertising executive who has a block at work that causes a meltdown… and a sentient boil on his shoulder that won’t stop talking. The pus-spewing boil was a metaphor for British prime minister Margaret Thatcher. “The things that were wrong with that film came out of my rage with Thatcher,” he tells me. “I was so fucking angry. I love humour in films but the anger became too didactic in that one,” he laughs.

He’s more hopeful now in 2024 than he was in 1989, especially after Sir Keir Starmer’s recent Labour Party victory. So enduring was his sense of justice, and his dislike for the Conservative Party, that he briefly entered politics and worked with Labour under Tony Blair. “Shooting propaganda,” he tells us.

Robinson’s biggest breakthrough was as screenwriter on Roland Joffé’s The Killing Fields (1984), a true story set during the Cambodian Civil War. The script, which earned him an Academy Award nomination and his first BAFTA, is written with a bruising contempt for conflict and Western military interference. “The original draft was a bit more anti-American,” he claims. But Robinson seems apathetic about whether the film, or any film for that matter, can provide change. “A famous producer once said to me, ‘Movies are entertainment and Western Union is for messages’ and that’s true. I’ve never watched a movie in my life that has changed my mind.” Two weeks after The Killing Fields was released, audiences were cheering on Sylvester Stallone tearing through the Mekong as Rambo. “He did 10 times more business than us too.”

One of the greatest things about the film’s script is how authentic and searing the dialogue sounds. Whether he is working on a screenplay or a book, Robinson famously speaks his dialogue as he types and performs the characters as they’re being written. This is why he is so adamant about how his lines are read by the actors. “Usually what is written is bullshit,” he admits. “But then a line will come out that sounds so right. It just comes out of your mouth.”

BRUCE ROBINSON © LAURENCE HILLS

Similar to his hero Charles Dickens, who also lived in Broadstairs, Robinson’s writing can flirt between the hilarious and the despairingly tragic. The author remains an endless source of inspiration and escapism. “Sometimes, when I’m alone in my car, I have this fantasy that Charles is in there with me,” Robinson says. “We are having a conversation and he’s asking questions about the speed or the inventions that have coalesced in the car.” At one point, it seemed as though he might adapt one of his hero’s great stories for the screen when David Putnam, his producer on The Killing Fields, asked if Robinson would write and direct a version of David Copperfield. “I researched it for three months,” he tells me. But the film was dropped. “It was the most desolate phone call I have received,” he says, clearly still hurt at the thought of it. “I didn’t only return to the book, I worked to really understand what it was like to live at that period of time.”

“Being at home with my typewriter is fab because I can have my bottle of red and I can do what I fucking like.”

Bruce Robinson

When Robinson researches something, he takes it more seriously than other filmmakers, committing himself to months and even years of intense study, and with a unique take on the story. He goes off on a fascinating spiel about the squalor of Victorian life, before reaching one of his greatest obsessions, Jack the Ripper, who Robinson investigated for 10 years for his book They All Love Jack: Busting the Ripper (2015). His office space, which overlooks the main house and the barn from a separate building, is a temple dedicated to uncovering the mystery of the Ripper. As Hills and I step inside, we are met with an intentionally haphazard detective bureau overflowing with research that includes cork boards with pinned evidence and volumes of vintage Victorian books on the subject. There are coloured A4 folders with scanned information from police investigations and from other historical archives that Robinson proudly flicks through. “I had two lightbulb moments in my life as a writer,” he says. “One was: what if the police didn’t actually want to catch the Ripper? That question gave me an avenue that set me on my way.”

The other lightbulb moment came earlier, when Robinson was in a Los Alamos hotel researching the script for Fat Man and Little Boy (1989), a film about The Manhattan Project directed by Roland Joffé. “The BBC had just run a show about Oppenheimer and I’m sitting on the hotel bed thinking, ‘What is this story actually about?’ It wasn’t just about fighting the Communists.” Robinson starts describing a string of theories involving Nazi scientists, Holocaust survivors, and chain reactors. His obsession over the story has made him an expert on the atomic bomb and the events surrounding The Manhattan Project, and—“Am I boring you?” he says, midway through a long, but gripping, monologue about the bomb. No, not all, Hills and I reply. “That’s OK. Sometimes I have to stop myself. I can go on.”

Watching Robinson eloquently devour a mystery in real time—whether it’s the Ripper or the atomic bomb—encourages my companion and I to nod our heads like bobble-dolls. His version of the story would’ve made Oppenheimer’s lover Jean Tatlock a more important figure (a common criticism of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023) is that Tatlock, played by Florence Pugh, is largely window-dressing). “It was the best thing I’ve ever written,” he adds, finally, on Fat Man and Little Boy. “The script was fucked up horribly by Roland. But that’s another story…”

Robinson wouldn’t let his work be rewritten twice. By the time Hollywood called a few years later, he was resolute in his principles and the ownership of his story… almost at the cost of his career.

He moved to Los Angeles to direct Jennifer 8. The Hollywood thriller was star-studded to the max: Andy García, Uma Thurman, Kathy Baker, and John Malkovich were at his disposal in his noir tale about an LA police detective. It should have been the perfect next step: one of Britain’s most exciting filmmakers going to Hollywood. But his time there was marred by studio interference and, more explicitly, a studio boss who began arguing with Robinson about the facts of his script:

Studio head: That’s not how an LA detective would spend his time off work.

Robinson: This comes from my research and discussions with these guys.

Studio head: Think you know more about America than I do, eh?

Robinson: I think I know more about these particular cops and how they spend their time off work, yes.

The studio head then threw a tantrum and threatened to end the project. Robinson was so jaded by the experience that he decided he would no longer direct, and shortly after the film’s release, and the LA riots, he returned to England to raise his family. “That affair,” he tells me, “it made me feel sick. It put me off directing.” This is when he and his wife found their Herefordshire farm, a world away from Hollywood. And all the better for it.

After the Hollywood experiment, Robinson became a successful author. Confined to the comforts of his home office, he wrote as he pleased, drank bottles of red wine (his writing fuel), and embarked on his auto-biographical novel The Peculiar Memories of Thomas Penman (1998). After Alistair Owen’s Smoking in Bed: Conversations with Bruce Robinson(2000), which is made up of a series of colourful interviews, a mystique developed around him that still persists.

In 2010, Johnny Depp approached him to adapt Hunter S Thompson’s novel The Rum Diary (2011) for the screen. Robinson returned to the director’s seat. It had been 20 years. “I told him [Depp] that I didn’t want him changing or reading my script differently,” the director explains. When Depp agreed, Robinson embarked on the project and a genuine friendship slowly grew. Depp still comes by the farm and once gifted Robinson a painting of Keith Richards he had made, which we see hanging proudly in the living room. “He’s a real sweetheart, Johnny. A lovely guy.”

The Rum Diary is a fun romp, but it is mostly remembered today as the film where Depp first met Amber Heard, who stars as the romantic interest. “I always tell my wife how guilty I feel about introducing them,” reflects Robinson. “But it wasn’t my fault. We were looking for someone to play the part of a 1950s dream girl. When she walked in for an audition, that’s exactly who she was.”

BRUCE ROBINSON. © LAURENCE HILLS

It’s been over 10 years since The Rum Diary was released. One of the questions most people ask me when I mention that I am interviewing Bruce Robinson is when he will return to directing films. “I would return but I’m getting a bit old for the fucking caper now,” he says. “Being at home with my typewriter is fab because I can have my bottle of red and I can do what I fucking like.” Shooting a movie and working from dawn to midnight on a set sounds strenuous at this stage of his life, he admits. But that doesn’t mean Robinson is totally against the idea. “I actually adapted the novel about my childhood into a script,” he says, “I’d love to make that before I shuffle off and if someone can cough up the dough. It’s very funny but also sad as fuck.”

As we follow the garden path away from the pool, back into the central area of the farm, which is flanked by the house, the large barn and stables, the office, and his wife’s studio, he recounts the story of how he discovered the identity of his real father. “He was a Lithuanian Jew who met my mother during the Second World War,” Robinson says. “He was a lawyer in America. When he died, his family found letters addressed from my mother in England. They began searching for a ‘Bruce Robinson’ and eventually, they contacted me. I have his photograph, too. Quite the thing.”

Robinson himself is a real family man. When we visit his old study room so that Hills can take photographs, he proudly shows us images from his wedding day in 1984 that are taped on the inside of an old journal. Walking past his wife’s studio, a country song performed by his son and daughter-in-law reaches our ears and fills the courtyard. For all the preconceptions one might have about Robinson (and they are true, he’s still very rock and roll—even without the Aston Martin), he is also a brilliant father and husband.

In the end, it is as hard to leave Robinson’s farm as it was to find the place. Not because we’re having such a good time, but because the 10 different local taxi firms he calls refuse to go so far out of their way. Robinson plants four new cans of Guinness on the table. “Have another beer, boys,” he says, and he starts regaling us with more tales of his time as an actor, a writer, a director, and a hellraiser, and we drink them all up. “When you’re finished, I’ll drive you back to the station.”