The Iranian-Danish filmmaker discusses Trump’s reaction to his new biopic, his original framing of the story as a Shakespearean tragedy, and how Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator informed his approach to making the movie.

“It’s going to be a fun day,” Ali Abbasi tells me as I shake his hand. “Donald Trump has just posted about us.” The Iranian-Danish filmmaker passes me his phone, and I read a statement that the former President of the United States had only a few hours earlier released on social media platform Truth Social (owned by Trump himself) regarding The Apprentice, Abbasi’s biopic digging into his rise as a real estate mogul and media star under the tutelage of ruthless solicitor Roy Cohn. The post is exactly what you would expect from the world’s most high-profile internet troll:

DONALD TRUMP’S POST ON TRUTHSOCIAL ABOUT THE APPRENTICE (DIR. ALI ABBASI).

Despite sporting a good-natured smile, Abbasi is clearly in two minds about the controversies surrounding The Apprentice, which struggled to find distribution in the US due to reluctance to touch the project ahead of the upcoming election, in which, of course, Trump has a starring role. “We’re like an orphan kid going from orphanage to orphanage, and being turned away at every door.” Abbasi says. “Nobody wants us!”

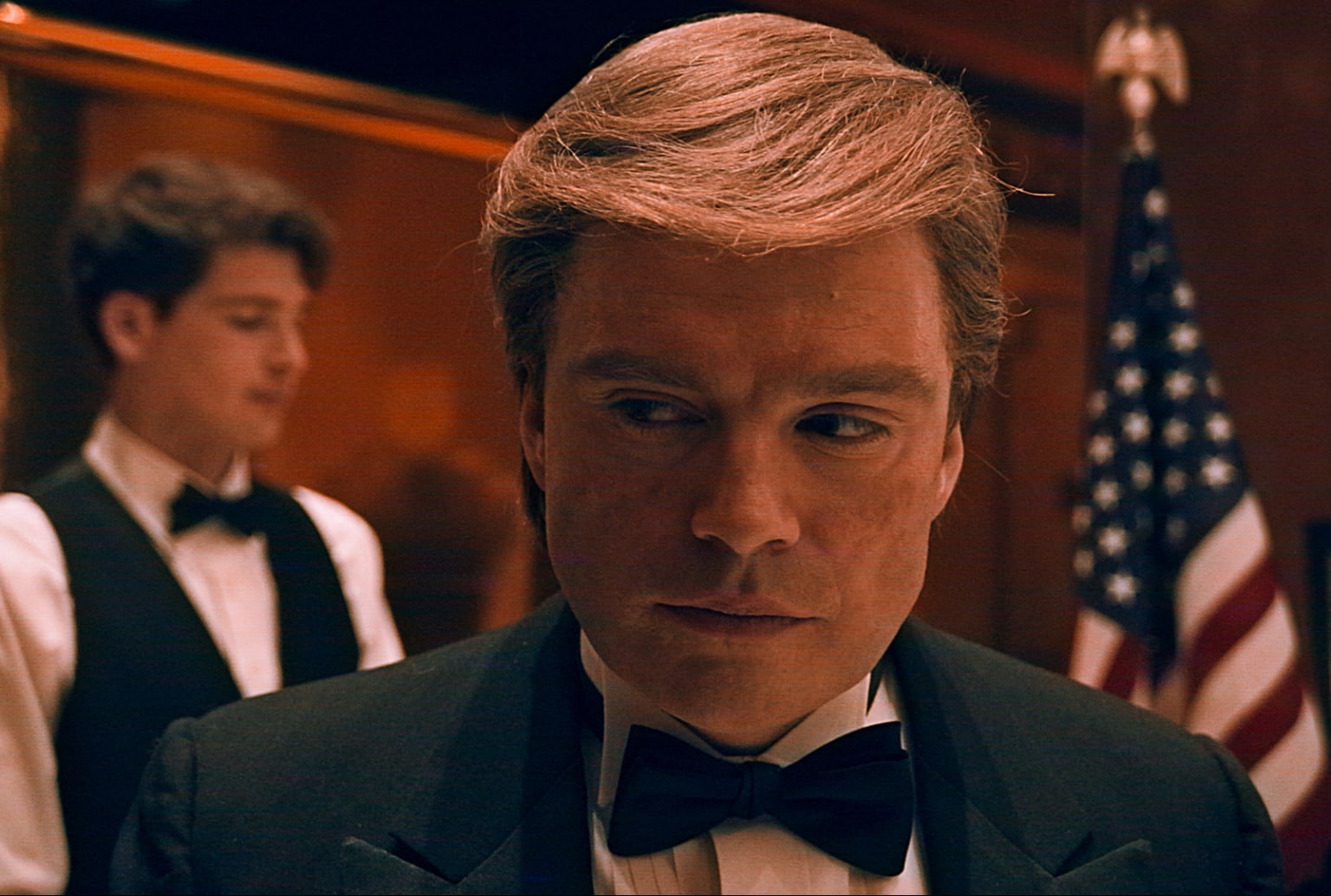

Abbasi has also had to contend with a lawsuit from Trump, as well as the simple fact that neither the left or right seem to be totally sold by The Apprentice, which rightly both humanises Trump and refuses to absolve him of his most loathsome actions. In the film, Trump is played by Sebastian Stan, first as a millionaire man-boy with billionaire ambitions, and then as the performance artist who has since become one of the most divisive people on the planet. In the beginning, he stutters and stumbles during business meetings and winces at the sight of his corrupt mentor Roy Cohn (a typically on-form Jeremy Strong) extorting a government official to win a trial. During the second half of the movie, Stan and Trump alike are transformed—the businessman now appearing more like a reptile wearing a flesh-suit than anything recognisably human. Abbasi films him as such, switching from the warm filmic quality we see in the beginning of the film to a hazy, dirty cam-corder, a nod to the rise of VHS in the 1980s and symbolic of Trump’s descent into performance and artificiality.

Abbasi joined A Rabbit’s Foot to discuss Trump’s reaction to the film, his original framing of the story as a Shakespearean tragedy, and how Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator informed his approach to making the movie.

Luke Georgiades: Do you think the controversy around the film is ultimately a good thing? Or can it distract from the fact that this is a work of cinema first and foremost?

Ali Abbasi: We’re like an orphan kid going from orphanage to orphanage, and being turned away at every door. Nobody wants us! I’ll do anything at this point—I’ll fly a jet in the air, I’ll belly dance for the Queen if that’s what it takes. It’s interesting, though. Every day I’m dealing with two sides. One side is telling me “you’re going to be responsible if he wins. You humanised him, and we’ll remember you for what you did. You’ll be the Jimmy Fallon of 2024. You’re going to be ashamed of yourself.” And the other side is “you fucking communist piece of shit, you think you can debase Trump? No way, you’re a nobody.” Well? Which one is it?

A lot of my friends from the business and a lot of my liberal friends were thinking “he [Trump] has nothing to worry about, this is a very neutral portrait of him.” [Abbasi gestures to his phone] Well, we got our answer today.

LG: I haven’t had a chance to look at the post, but I can’t imagine it was favourable towards the movie.

AB: It’s not [laughs]. I don’t think he has a lot of respect for directors. In that way, he’s a bit like WGA [Writers Guild of America].

SEBASTIAN STAN AS DONALD TRUMP IN THE APPRENTICE (DIR. ALI ABBASI).

LG: It’s interesting to me because Trump knows better than anyone that all press is good press, and any other politician would think twice before bringing that attention to this movie, they’d sooner ignore it completely.

AB: This is the reason he has been able to do politically what no other right-wing demagogue has been able to do before, which is to believably sell himself as a man of the people, as an authentic human being. Any intelligent person can see that there’s no real content in what he says, he speaks in hyperbole, but he sounds more authentic than your average politician who incessantly repeats scripted talking points. A lot of right-wingers have asked why I didn’t make a movie about Hunter Biden….who the fuck cares about Hunter Biden? The biggest thing he’s done is take crack. That’s not worth six years of my life.

So Kamala Harris wouldn’t tweet about this film if we made it about her, which would be too boring to watch anyway, but he would, because he’s projected himself as an authentic human being. But does that exonerate him?

LG: Not at all.

AB: Of course not. I was just reading about The Great Dictator, which was illuminating, not because there are parallels between Hitler and Trump, but there are parallels between the situation. Charlie Chaplin started shooting The Great Dictator six days into the second World War. It was ongoing for six months and came out, and it was interesting because the idea for The Great Dictator came from a screening that Luis Buñuel had hosted for Chaplin and a few other filmmakers of Triumph of The Will, and everyone was terrified…except for Chaplin. Chaplin was laughing his ass off. That was his approach to his film, “I’m going to deconstruct this shit, because it’s so fucking stupid, but also so human.” Later on, he regretted doing the movie on a level, because at the time he hadn’t realised the severity of what was happening in those concentration camps when he started making it. But if you look at the movie from the present day, you think: “what amazing timing, what an amazing leap of faith for humanity that film was.” We’ve forgotten that there was a time where these things were happening and people had the same concerns as they do now. The same way Chaplin didn’t think he was exonerating Hitler by bringing him down to a human level, we aren’t exonerating Trump. We’re practising empathy, but not sympathy.

LG: They flew a banner over a recent Trump rally in Pennsylvania jokily imploring him to watch the film. If he did watch it, what kind of response would you be hoping for?

AB: My hope? [Abasi slides his phone across the table, showing that morning’s statement from Trump]. That’s my hope. I’m sad he left me out of the conversation there. But I’ve said it before, I would happily watch the movie with him, and answer any questions he may have. That’s not a joke. It’s a real offer. This is a movie about real people and human characters, so we have to deal with them as human beings.

JEREMY STRONG AND SEBASTIAN STAN IN THE APPRENTICE (DIR. ALI ABBASI).

LG: I found it hard to shake the slimy feeling that the second half of this movie left me with. Was it part of your intention to make a movie that leaves your audience feeling compromised in that way?

AB: I didn’t want the movie to be about an alien who landed on Earth and became evil. This could be anyone. Or, if not anyone, it’s a trajectory of which the ingredients are not hard to come by in human nature. A US distributor asked me what I think the movie is, and I told them I thought it was a tragedy. It’s a Shakespearean tragedy. And they’re like “ah…tragedy doesn’t sell, let’s call it a monster movie.” It is, of course, that also.

LG: There’s strong hints of Frankenstein throughout.

AB: I was watching Frankenstein at the Academy Museum a few weeks ago, and there’s a sentence at the beginning where Dr. Frankenstein talks about how in the absence of God he created this monster in his own image. That could be the headline of what Roy Cohn is doing. In a way, this isn’t a Trump movie, but it’s a transformation movie. If you’re interested in knowing how someone could become the person he is, you’ll find your answers here. This isn’t about the guy who’s running for office.

LG: Halfway through the film the way you shoot shifts more into this documentary style, it feels like there’s a lot more of this handheld camera, sometimes dirty cam quality.

AB: We went after this archival footage, newsreel feeling because at the end of the day, these are media characters. They’re born and raised in front of the camera. The seventies archival footage and newsreel were shot on film, so they have that cinematic quality.. In the 1980s, broadcast video became dominant, and it feels a bit strange, a little too sharp, almost, and constructed. That’s a good metaphoric way to follow what happens to Trump’s character, starting in a more authentic, organic way and slowly getting into the vulgarity, excess and constructiveness of the man he became in the 1980s.

MARIA BAKALOVA AND SEBASTIAN STAN IN THE APPRENTICE (DIR. ALI ABBASI).

LG: I think one of the great things about Sebastian’s performance in this is that he slowly introduced the mannerisms of Trump into the film instead of immediately rattling off an SNL-type impression. How did you and him work out the kinks of the character’s tone and physicality?

AB: Mr. Trump in the 1970s wasn’t anything like how he is now. He was more rational, he sounds like any other young, ambitious guy who tries to act a little older and smarter than he is, not unlike most young entrepreneurs. These mannerisms we associate with him come along the way. What’s remarkable about Sebastian’s performance is that he tries to do as little as possible, not as much as possible, to conjure the character. The day we did the final scene was hard for Sebastian, because at that point he felt we were edging towards that cartoonish quality, which isn’t unlike Trump either. But we were continually calibrating and judging how far we should go.

LG: How did you and production designer’s go about figuring out what Trump’s living spaces were going to look like? I caught a Double Indemnity poster in the background of his living room early on in the movie.

AB: And Citizen Kane! The good thing is that there’s so much historical documentation available to us, so we leaned into them, down to the detail of this portrait of him in which he’s missing a leg. Alex, our production designer, and her team did a fabulous job dancing with reality in that they didn’t try to capture total historical accuracy, but the vibe that his space opens up and becomes more vulgar as he ascends in wealth and power.

SEBASTIAN STAN IN THE APPRENTICE (DIR. ALI ABBASI).