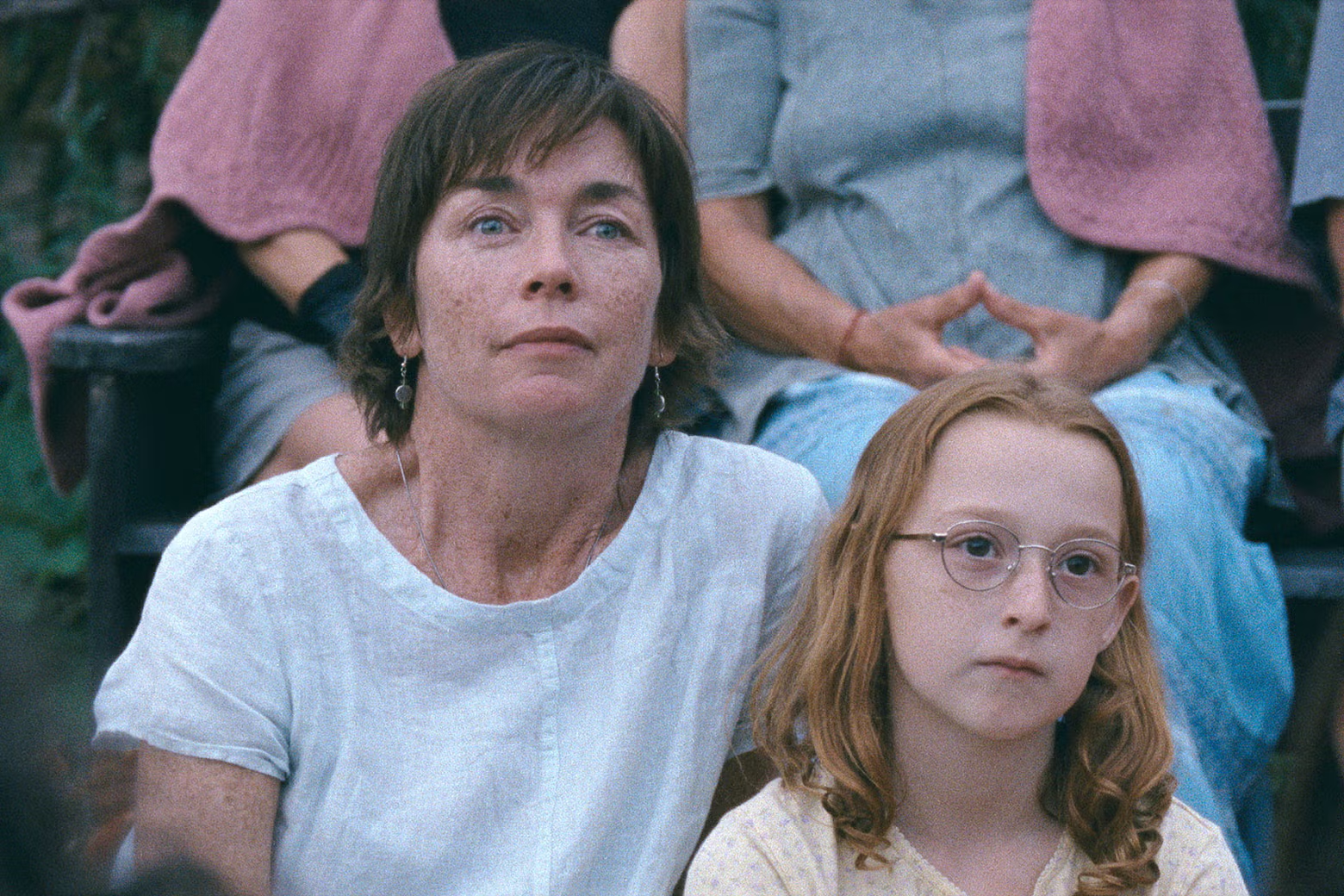

Midway through Janet Planet, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Annie Baker’s semi-autobiographical film, a mother and daughter walk together in sublime sun, the moment hushed except for crickets chirping and a gentle breeze. Breaking the quiet, Janet (Julianne Nicholson) asks: “What should I do?” “You’re asking me what to do?” responds 11-year-old Lacy (Zoe Ziegler). “You have to break up with him.”

It’s a scene which sums up the push and pull of many single parent-child relationships. Janet, betraying her uncertainty about her own life offers up the jurisdiction to her not-yet-teenage daughter, going against ideas of what parenthood should look like by wearing her own fallibility boldly. In Janet Planet, the supposed boundaries society demarcates between adult authority and juvenile obeisance are regularly overstepped, or toyed with. Janet and a friend take narcotics while Lacy, waiting patiently at the edge of the frame, fetches water; late at night, with a conspiratorial frankness belonging more to a friend than a guardian, Janet confesses to Lacy her greatest flaws. Ricocheting between parental responsibility and independence is the paradox at the pith of single parenthood, which Janet Planet captures acutely.

There has been no shortage of single parents in the history of cinema. Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid (1921) (which made Jackie Coogan one of the first child stars in Hollywood) imbues the act of raising a child alone with the glow of heroism. Single mothers, on the other hand, became widely tied to tragedy: the downtrodden protagonist of Wu Yonggang’s The Goddess (1934), forced into sex work to care for her son; or the wily, deviant single mothers of dramas like Mildred Pierce (1941), who were weighted with a social stigma that would last until the 1970s. Later, comedies like Big Daddy (1999) or Little Man Tate (1991) follow in the footsteps of Chaplin’s classic by unquestioningly advocating for a fulfilling, but entirely self-relinquishing, form of single parenthood. This template for the valiant, hard-working and altruistic single parent can also be found in Erin Brockovich (2001) and To Kill a Mockingbird (1962).

On the flipside, in romcoms like Maid in Manhattan (2002), single parenthood is a shorthand for strife and hardship, which is, rather than idolised, to be escaped. This is a returning trope in The Idea of You and A Family Affair. Tellingly, their romances are between single mothers and characters with a queasily close relationship to their daughters (including, with the former, a popstar crush), giving an uneasy, slightly Freudian edge to the message of self-prioritisation.

Unlike this duo of recent releases which have brought single parenthood back under the lens, Janet Planet is much more pensive in its wrestling with what parents owe to their children, and to themselves. It is also rare in its portrayal of the intricacies of its central relationship, perhaps presaged by Sean Baker’s The Florida Project (2017), which gives a child’s-eye-view of life in a ramshackle motel. First-time actor Bria Vinaite—scouted by Baker from Instagram—brought a rawness to the role of single unemployed mother Halley lacking in critical flops such as Fathers and Daughters (2015), which perhaps strive too hard for emotion.

Baker’s film takes a much more subtle approach, inviting debate about Halley’s character. It seems significant in The Florida Project that Halley’s sole friend Ashley (Mela Murder)—another mum, who is not single—personifies this judgement and brings about the film’s final disaster. Remaining coy when asked for his thoughts on Halley’s parenting, Baker said: “I’ve talked to audience members who’ve come out and said, ‘Ooh, that mom doesn’t know what she’s doing’. But the goal is to create a discussion and also, hopefully, create at least empathy for her.”

This fleet of emotionally attuned single parent films can be mapped onto a rising real-life demographic, meaning more departures from too-pervasive nuclear family narratives are still to come

Both The Florida Project and Janet Planet disrupt the rose-tinted vision of childhood, but shadows show more deeply in Charlotte Wells’ debut Aftersun (2022). Rather than the enmeshed bond of Janet Planet, Wells’ film is about a relationship always in some way out of reach, visible only through the whitewashed prism of memory and old camera footage. Despite this distance, for Wells it was important to dismantle the “trope around single fathers in film” that “they’re ‘deadbeat dads’”: “Calum [Paul Mescal] is absent in some ways, but when he’s present he’s very present”. Calum conceals his problems from Sophie (Frankie Corio), but she, like Lacy, can see the imperfect person beyond the parent.

This fleet of emotionally attuned single parent films can be mapped onto a rising real-life demographic, meaning more departures from too-pervasive nuclear family narratives are still to come. Adura Onashile’s Girl (2023) draws on her upbringing in a Glaswegian apartment block, following an 11-year-old girl as she gains her first taste of independence. But her mother, wary of social services, fights against this and attempts to keep their mother-daughter sanctuary intact.

Perhaps what binds these films together is their delicate rendering of the small worlds made by single parents and their children; their insularity. In Janet Planet, Lacy’s galaxy is at once minute—only three outsiders enter her mother’s orbit over the course of one summer—and vast. Left to her own devices, her imagination is free to roam. These films are underpinned by the eclectic nature of these children’s imaginations and the uniqueness of their universes.