It’s like a bad joke. A German, a Czech and a Welsh woman walk into a bar, except the bar is the patio outside the Bergman Center where Anna Lu, Martina and I are looking at an enormous facsimile of a chess set. Serge Gainsbourg plays on some loud speakers. Anna-Lu’s green eyes crinkle up at the edges when she smiles, which is often, in a way that makes me think from far away she was Renate Reinsve (who happens to be the guest of honour at this year’s Bergman Week). She comes over to me after hearing my voice “I love British accents!” she tells me, “it’s where I first travelled after the Berlin Wall fell down”. Anna-Lu is an actress, the socialite of Fårö, if such a thing existed.

Fårö is an island that defies easy categorisation. After a train, a bus, a ferry and a car ride, I’m finally here, in Gotland, on this rugged and isolated outpost straddling the Baltic sea. It feels worlds away from Stockholm. Or any civilisation, for that matter. “You’ve arrived at the end of the earth” a French stranger says to me with a smile while waiting to board the ferry. Its atmosphere is permeated by the fact that one of the biggest Swedish cultural exports of all time lived and died on the island. It’s a place without a hospital, or a school, or a taxi, and only one small ICA supermarket, but has an abundance, for its size, of Michelin-style restaurants. There’s a small outdoor art gallery and an Americana junkyard cafe-restaurant that serves crepes and plays tunes from a jukebox, next door to a cliffside hotel.

Bergman lovers rub shoulders with those that also flock here for Politicians Week as well as holidaymakers (a large percentage of Gotland is made up of wealthy Stockholmers on vacation). Its tourism was probably helped by Mia Hansen Løve selecting itas the setting for her 2021 film Bergman Island, and yet its still referred to as “Sweden’s best kept secret”.

For five heatstruck days in June, a combination of film, performance, talks and parties are held against a backdrop of eternal daylight, rocky shorelines, and silence punctuated only by the sheep that dot the island. Depending on your allegiance to the great Swedish master, this will sound like your idea of heaven or hell. This in fact, was my fourth time on the island, but the first time I would be completely, totally alone.

It’s 9pm and the sky against the skinny trees is pink and white, coy, like a blush, only one that goes on forever. There is no soul in sight except Anna-Lu, Martina and I, not even Death on the horizon in a black cloak. There’s no one in sight because I have accidentally slept through most of the opening night “mingle”. It’s like that scene in Frances Ha, except instead of awaking dazed and confused in a Parisian pied-a-terre, I’m in a hot and stuffy bedroom in a desolate cabin that the owner tells me her grandfather died in. “It’s okay though—he was the kindest man. His ghost won’t do you any harm” she told me with a smile. This is my first night on Bergman Island and the sky stays white and the sun does not go down and we are somehow having a conversation about childhood trauma. “I was born with this face. But I have a very disconnected relationship to it, you know, like, the way I think about it was like, my parents happen to fuck at a certain time.” Martina, who comes to Bergman Week every year the Isabella Rosselini lookalike slurs to me, one cigarette jauntily in her hand. The booze only seems to make her more elegant, as if repose was her natural form. It is my first hour on Fårö and I am already planted inside a Bergman film, a sign of things to come.

Lack of sleep will be a theme. “It’s a festival for early risers,” Johan Hallström, artistic director of the festival, tells me. (If the name sounds familiar then that’s because it is. Hallström is the progeny of Swedish film royalty, the son of director Lasse Hallström (The Cider House Rules, Chocolat). He’s not wrong. At this year’s festival, themed “Cirkus” for the 20th anniversary, you can start your day off with a searing evisceration of the brutal reality of infidelity (Faithless, directed by Liv Ullmann, script written by Bergman) or the sadomasochism of school days (Torment), or take part in some Bergman-themed VR. There’s talks on things as wide reaching as Bergman and the occult, or Bergman and clowns (if you can speak and understand Swedish). Afternoons are dedicated to modern films. Previous year’s have screened films from Aubrey Plaza and Greta Gerwig, but this year’s focus is predominantly Scandi: guest of honour Renate Reinsve has two new releases, Cannes darling Armand and A Different Man showing, alongside Mika Gustafson’s Paradise is Burning and Dag Johan Haugerud’s Sex.

If you’re lucky, you may get the chance one afternoon to watch Sawdust and Tinsel, The Magic Flute or Hour of the Wolf in Bergman’s own personal 14-seater home cinema on 35mm. Bergman would religiously sit in here everyday, from 3pm, watching films from his private collection. Emilie Meyer, who is here with her parents on holiday, is telling me a story, in her perfect English drawl. She was about to watch Sawdust and Tinsel in Bergman’s home cinema. “So I’m out of my seat and I’m sprinting, picture it. I’m running barefoot in a field. I’m pulling up my skirt. And it’s happening, before I know it. I’m peeing. I’m peeing in the front garden of the Mia Hansen-Løve house. I have to use leaves to dry my ankles. Then I’m running back toward the Bergman house as the door is closing.I’m bolting now, sprinting. I make it! I’m in. I’m in my armchair and I’m smelling a tiny bit like pee and I feel like I’ve broken an unbroken rule and god does it feels good.” I think the ghost of Bergman would be amused by this at the very least.

We spend one night at the junkyard bar, Kutin’s Bensin it’s called, and it’s the place to be: the night of the Bergman film quiz. I’ve come too early which means crashing a Norwegian film dinner and trying to make conversation with people who look at me puzzled. I am heatstruck and hungry. This place, also seen in Bergman Island, has French staff and serves only sweet and savoury crepes. Swedish-style. Named after all the classic Hollywood stars: Marilyn, Elizabeth, Jimmy, Marlon, that Elvis cat…. It’s an interesting amalgamation.

Near the jukebox in the corner sits Alvin, “like the chipmunk” the waiter. I think he’s 12, or maybe 14. He is the only one who speaks to me. “I thought you were from the Balkans. You remind me of my Slavic cousin”. He tells me he’s almost sixteen and emphasises how soon his birthday is,in the way that teenagers do, where every second counts, where one month is the difference between the bigger kid in the year above or the being the baby of the year group. I make a joke about TikTok. “I don’t use social media. My screen time is only 1 hour a day. I’m not going to get the brain rot”, he says. I ask Alvin if he’s seen any Ingmar Bergman movies. “No”, he tells me. “But have you seen One Day on Netflix?”

The quiz is bustling, everyone from the island has turned up or so it seems, crepes and beer and ice cream are flowing. Vincent and Elizabeth are here on holiday to look at birds and they can’t keep their hands off of one another. I wonder if maybe I’m wrong about the Bergman curse on relationships and maybe his films have some secret aphrodisiac effect I don’t know about. I mean, the Polish couple who end up winning the quiz are spending their honeymoon on the island.

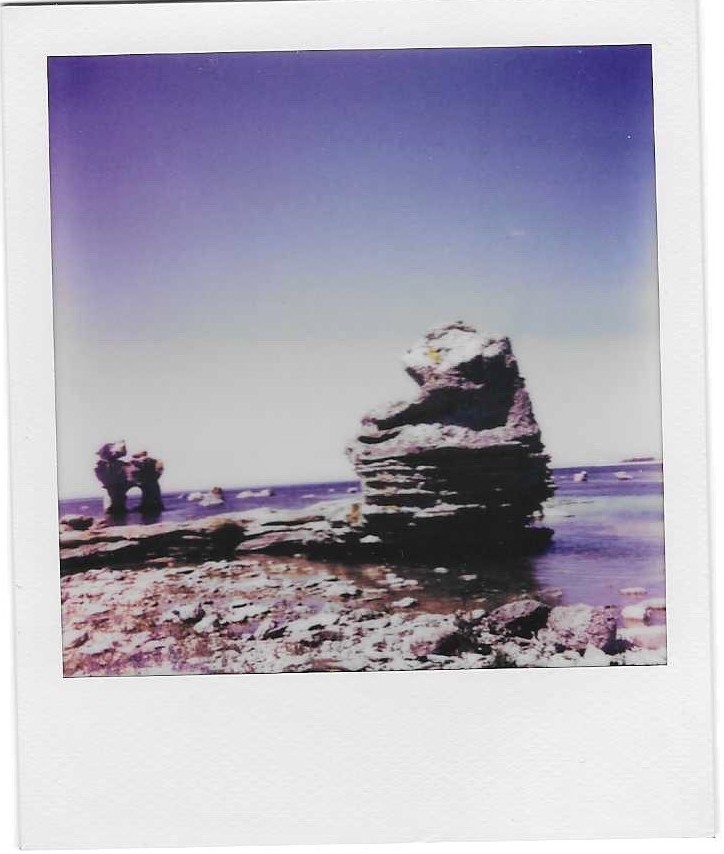

One morning I split off from the Bergman Safari bus tour to wander the limestone stacks, called ‘rauks’ that tower over and through the water, mediaeval and silent. They contain the sounds of the past. It’s 2021 and my 28th birthday and my ex and I are arguing about the car, arguing about how I very much want to leave him and how he won’t accept this, staring up at a brown wooden ceiling, wondering how I conjured up the spirit of Bergman, or at the very least, ended up starring in Scenes from a Marriage. I remember thinking this island is cursed for couples in love.

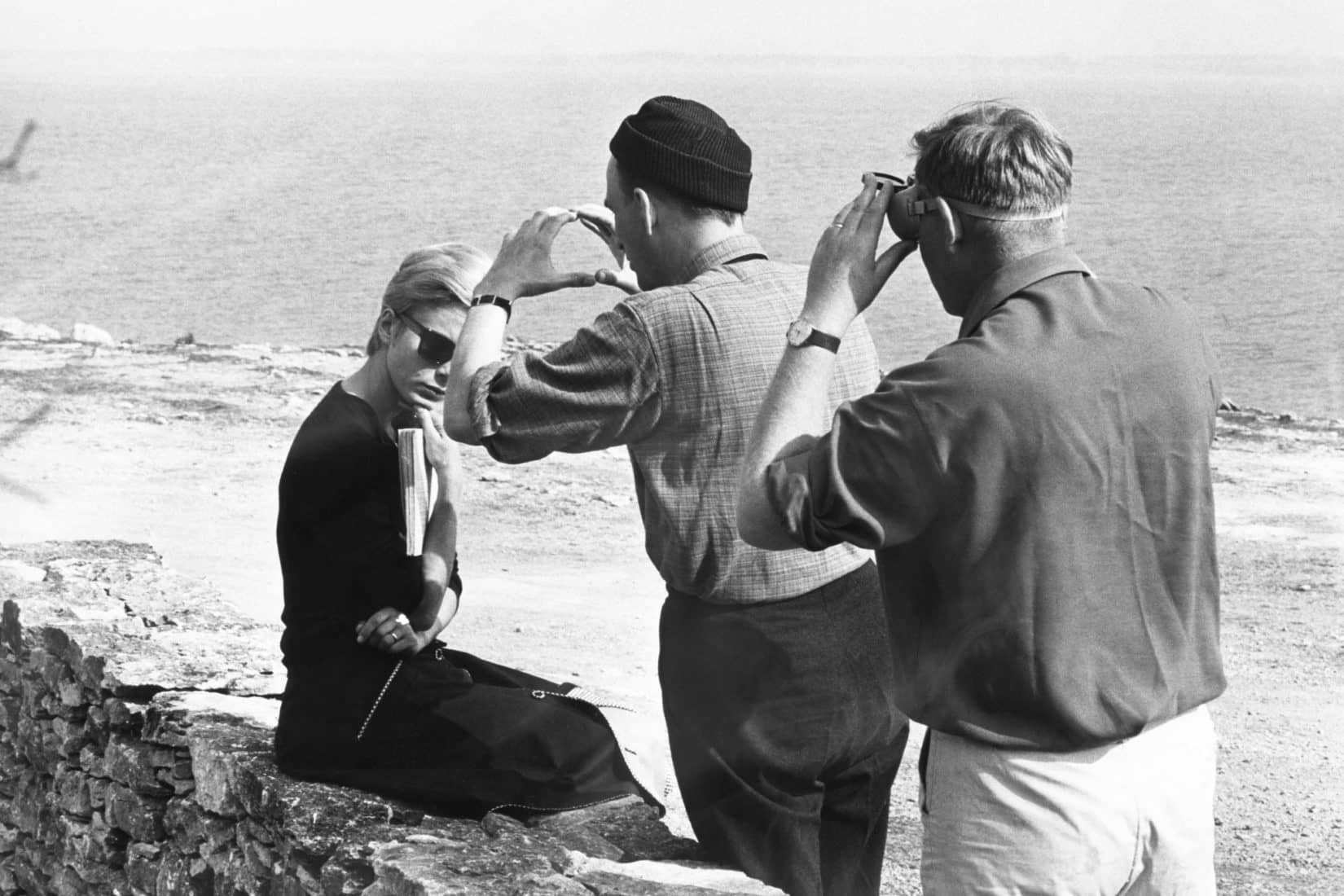

It’s 1960 and Ingmar Bergman visits Fårö for the first time, about to shoot Through a Glass Darkly, unable to travel to his original idea of the Orkney Islands. “This is your landscape, Bergman!” he announces to himself. It is love at first sight. It’s 1965 and Bergman sits opposite the pale-faced actress with the long lean body and elegant fingers and freckles, whose sparkling blue eyes will never change. His face is close to hers, he’s really paying attention. She is Norwegian, this Liv Ullmann, and he will marry her and give her babies and she will live on forever in his films, this most recent one being Persona. He strokes her chin gently, they’re both in black, and the rauks are barely noticeable to them, just another part of the autumn landscape in this barren post-apocalyptic land.

This beach is mediaeval and futuristic at the same time, the rocky beaches are like landing on Mars. Stacks of jagged rubble and the unnatural howl of the wind which never stops and seems, like the shrieks of sheep, to be constant. These rauks! They’re Kubrickian monoliths from 2001! They’re a movie set made by nature. No wonder Bergman was so enchanted with it.

The festival is less like conjuring the dead than travelling to a place where time has stopped.

It’s the characters of the island that embody the true spirit of the festival. All of the people the colour of a dark terracotta, sun worshippers, the type of place where you can imagine Bergman envisioning his “nightmares saturated in sunshine”. Lottie, responsible for the bar and cafe at the Bergman Center tells me I’m “black and blue” and instructs me gently to sit in her chair in the shade and drink her own special cucumber and herb brew to hydrate myself. She had slept in the cinema before opening night, tucked up on a blow up bed amongst all of Bergman’s ghosts.

Anna-Lu is blasting down the road to the song ‘Sister’s Are Doing It For Themselves’, dressed like Liv Ullmann in Passion of Anna, saying how Bergman wouldn’t have liked her because she would’ve said no to any romantic gestures on his part. “I would’ve been too weird and strong for him”, she says. Anna, who owns the cabin at Marpes that I stay in, met her husband Kurt at a Midsummer dance on the island 38 years ago and never left. “Bergman paid the owner of some barns down the road so he could burn them down for one of his films”, she’s talking about Shame. Bergman’s touch is still omnipresent here, the mark of the director never really went away.

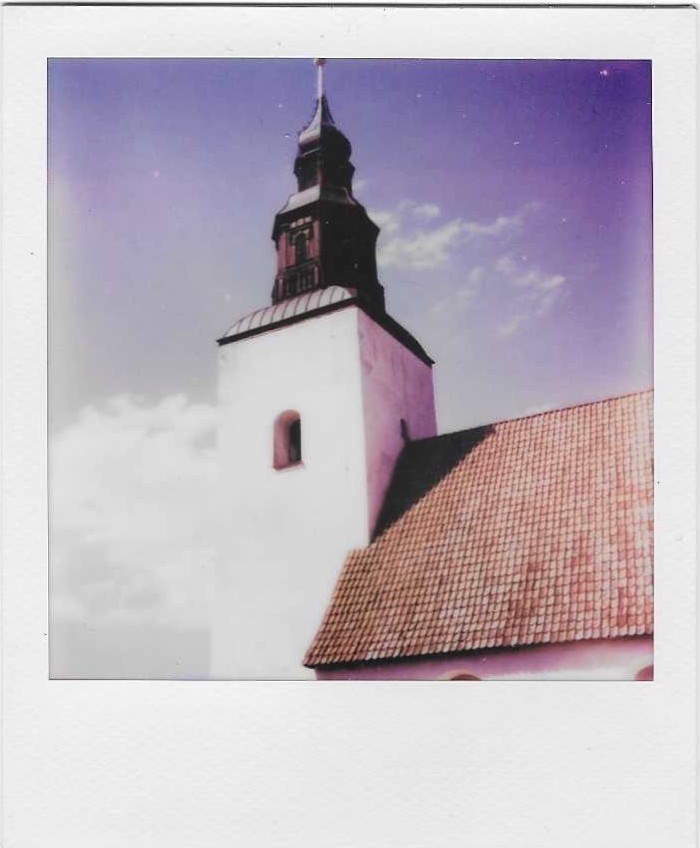

It’s Friday and what feels like the hottest day of the year. Before I leave the island for good I want to do two things. The unlittered shoreline at Fårösund lies unbroken, untouched. There are barely any people around. I dive into the sea which is surprisingly warm. If I squint, I can see myself from three years ago, sitting on a blanket drinking riesling with the grey-haired older man, our shoes off, our clothes covered in sand, our faces turned toward one another in conspiratorial silhouette. I think we look happy, or at least in the vague imprint of the memory we do. Before I leave to get my ferry, I walk down the dusty road toward the church, Fårö Kyrkan, and open the gate. Here the breeze and trees are shading the tombstones that look out toward the sharp blue sea, a sapphire so bold.

In a little patch near a stone wall at the back of the cemetery, there he is. On an oval headstone, Ingmar Bergman, buried with Ingrid Bergman (not that Ingrid Bergman). This little patch of land could be anyone’s, this tombstone anyones, so unassuming, yet it still feels like some kind of magic, to be standing here, with the Swedish genius who knew so much about life and love and its darkness so close, underneath my feet.

Main image: Bakombild. Bibi Andersson, Ingmar Bergman, Sven Nykvist