The further you travel down the sprawling whirlpool of Japanese director Seijun Suzuki’s filmography, the deeper you become ensnared (joyously, I’ll add) in his utterly unique vision of noir.

Film critic Grady Hendrix once compared Suzuki’s sensibilities as a filmmaker to that of a hyperactive child, whose singular cinematic goal is to entertain and be entertained himself. His films burst with imagination and feel untethered from many of the traditional “rules”’ of cinematic grammar, with the filmmaker not operating on the same plane of logic as other filmmakers, but instead relying on a cinematic logic that exists of his own making. Children are the greatest of impressionists and if we take Hendrix’s analogy to heart, then it becomes of little wonder why Suzuki’s films, which revived the dying yakuza genre, were conjured up by the master with such childlike exuberance for the form.

He’s now regarded as one of the Japanese New Wave’s most essential pioneers, but Suzuki was first and foremost a company man. In 1954, the Nikkatsu studio—known for making cheap exploitation flicks—employed the amateur filmmaker to churn out B-movies at a rapid-fire pace. The studio enforced a rigorously tight shooting schedule consisting of one week pre-production, a 25-day shoot, and three days in post. Nikkatsu controlled the script, it controlled the casting, and it controlled the budget. It seems a miracle, then, that any Seijun Suzuki movie looks the way it does, and if you’ve ever had the pleasure of watching even just one of his 40 films made under the Nikkatsu banner, you’ll know exactly what I mean. Suzuki’s movies are vibrant explosions of the avant-garde, not so much wearing the guise of popcorn entertainment, but entwined with it, and closer inspection of his filmography reveals that Suzuki’s indistinguishable authorship wasn’t formed in spite of Nikkatsu’s chaotic work practices, but more as a response to them.

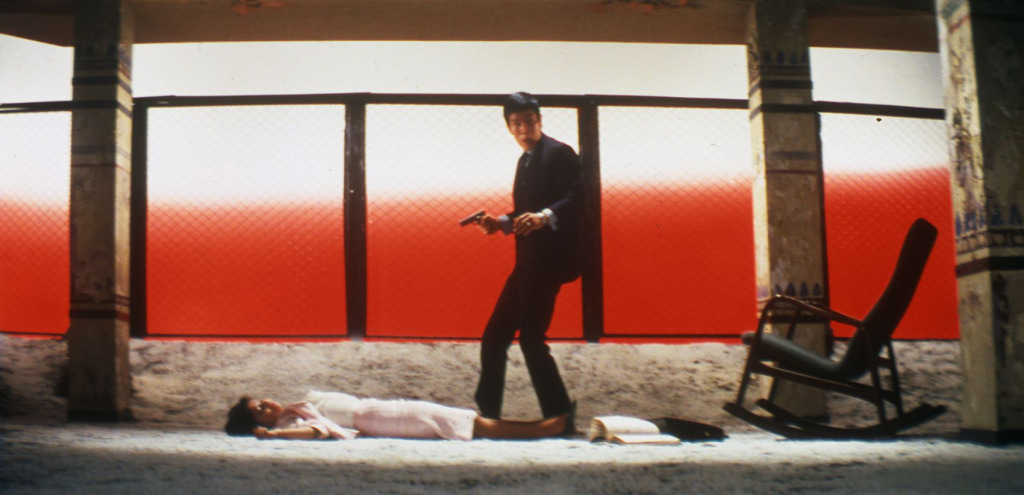

Take the production design that would become a trademark of Suzuki’s work. Alongside art director Takeo Kimura, another in-house Nikkatsu employee, Suzuki developed an expressive pop-art visual style that relied on bold colours, otherworldly backdrops, and fantastically artificial sets, giving films like Gate of Flesh (1964) and Tokyo Drifter (1966) a dreamy, quintessentially impressionist edge. It was the antithesis to the idea that noir should inherently be gritty and rooted in the real world. But as boundary-pushing as Suzuki and Kimura’s experiments were, their style can as much be attributed to practicality, with the cheap and quick-to-throw-together sets working in tandem with the high-pressure time constraints and micro-budget placed on them by Nikkatsu.

It was the very limitations of working within a B-movie framework that informed Suzuki and unwittingly encouraged him to breathe new life into the yakuza genre, which had long grown stale by the time he joined Nikkatsu. Similarly, if Nikkatsu hadn’t relegated Suzuki to second billing on its double features, would he still have developed the snappy, ultra-streamlined editing and pacing that were essential to keeping audiences planted in their seats? Perhaps not, though the same sensibility has gone on to mark his filmic legacy. Every move Suzuki made was an effort to alchemise the little opportunity and resources he was provided into something radically different from any other Japanese movie on the market. His 40-film body of work under Nikkatsu remains a fine example of how low-budget filmmaking can be a trigger for artistic innovation.

Ironically, Suzuki’s love and understanding of pop-genre filmmaking also fed his unassuming ambitions as an avant-gardist. He was an admirer of westerns, crime, noir, and the like, and even his leading men sometimes felt as if a caricaturist’s drawing of the western anti-hero had suddenly sprung to life from the canvas. You’ve seen Clint Eastwood in the classic Leone westerns whistling ominous melodies as he approaches gangs of outlaws. In Tokyo Drifter, Suzuki takes the trope a step further, having rogue yakuza assassin Tetsuya “Phoenix Tetsu” Hondo (Tetsuya Watari) taunt his enemies by belting out his character’s balladic theme song word for word. He sings: “As long as I am a flower that needs no dream / flowers will perish and the dreams will perish / after all, if I have to perish, I’m going to be a manly flower / I abandoned my love for the sake of my duty / ah, Tokyo Drifter.” It’s a devilishly satirical deconstruction and loving wink to a genre that Suzuki notably felt inspired enough by to mould in his own mischievous image.

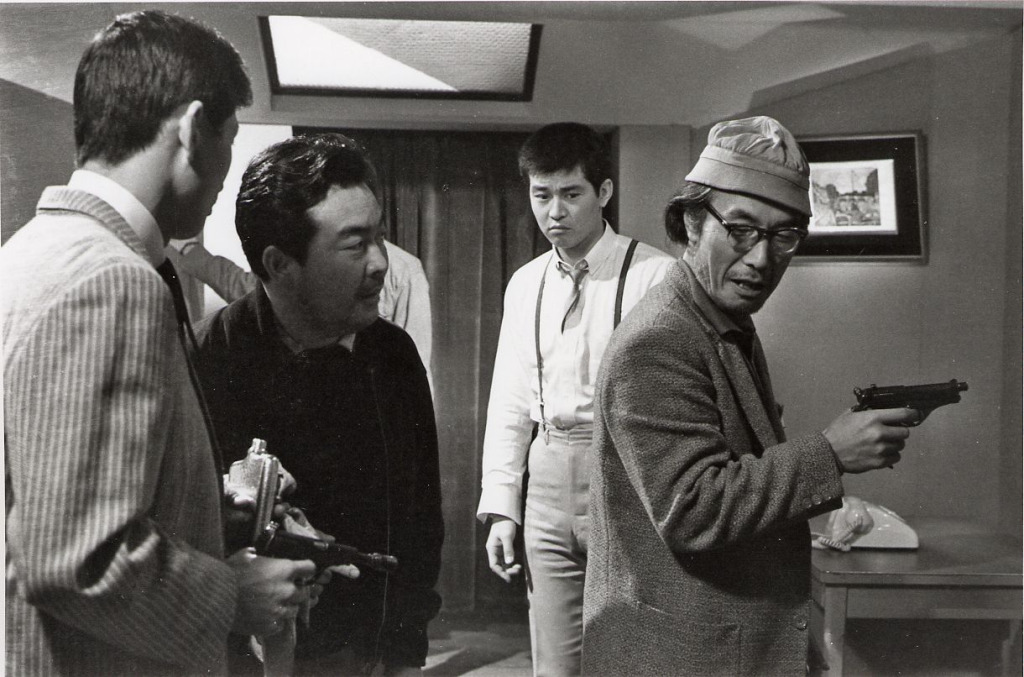

Joe Shishido, who starred in three of Suzuki’s career-defining films—Branded To Kill (1967), Gate of Flesh, and Youth of the Beast (1963)—especially comes across like a funhouse mirror reflection of the typical Western action hero, particularly Ian Fleming’s British secret service agent James Bond. The story goes that Shishido, having struggled to find success as a young actor due to his “blandly handsome features”, decided to undergo cheek augmentation surgery in order to reinvent his career. His gleefully ludicrous scheme worked, and Shishido, each cheek the size of a bongo drum, is now lauded as one of the all-time greats of yakuza cinema. Nowhere does the actor’s idiosyncratic approach shine brighter than in Suzuki’s films, though, his now mannish, chipmunk-faced protagonists providing the perfect subversion to Fleming’s suave and dashing womaniser.

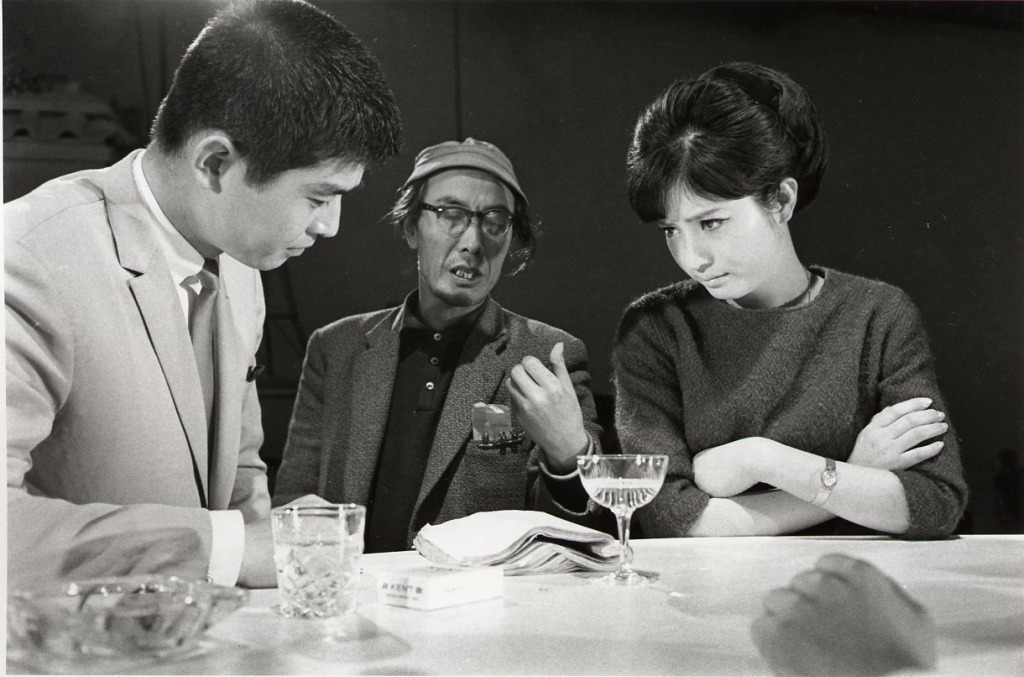

In Suzuki’s masterpiece Branded to Kill, we see Shishido straddle both cool and the absurd in astounding equilibrium. The premise of the film is as bulletproof as they come: after botching a job, the number three yakuza hit man in Japan is marked for death and becomes the target of numbers one and two. It’s a noir through and through, rupturing with sex, violence, cynicism, betrayal, and intrigue, and featuring a dynamite femme fatale performance from Annu Mari as the death-obsessed Misako Nakajo. But Branded to Kill, true to form for Suzuki, is the absurdist man’s noir: a film that rearranges the DNA of the genre like a Rubik’s cube before putting it back together as a bizarro version of its previous self.

If you saw David Fincher’s The Killer last year, then Branded to Kill’s approach to the noir leading man won’t feel totally alien. But Suzuki tackles the genre with more splash, style, and aggression than Fincher does. Like Michael Fassbender’s titular killer, the character of contract assassin Goro Hanada in Branded to Kill is actually diabolically bad at his profession. This isn’t your typical noir anti-hero: he botches hits, is made a fool of by other characters, and fumbles his way to the end credits on the merit of pure dumb luck. His defining characteristic is his sexual fetish for boiled rice, which he asks his women to prepare before copulation—another instance of Suzuki mischievously poking fun at the genre’s über-masculine, sex-crazed Western counterparts, particularly Bond, whose seduction of a woman usually comes after a laboriously made martini.

Humour is at the heart of Branded to Kill and makes up the nitroxide that fuels its most aggressive artistic tendencies. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the film’s farcical final act, which sees Hanada undergo psychological torture by the number one ranked hit man in Japan, who accomplishes this by moving into his apartment and lording Hanada’s approaching death over him during every waking moment. It’s a turn from hard-boiled noir to odd-couple slapstick so sitcom-coded that it’s all but missing a laugh track. Under Suzuki’s direction, the switch feels less jarring. It’s a natural evolution of his wonderfully anarchic cinematic logic.

Suzuki was a maverick of Japanese cinema. His rebellious streak elevated traditional B-movie fare to high art to such a degree that he was constantly at odds with the studio that was funding his pop-art experiments. If the studio ordered Suzuki to make a cheap and smutty sexploitation flick, he would go away and return with a film like Gate of Flesh, a tragedy about the collective trauma of post-World War II Japan. What makes the finished product so disarmingly accomplished is that it doesn’t sacrifice an ounce of pulp for its politics. It’s as entertaining and visually dazzling as it is socially resonant—as much a popcorn movie as a commentary on the time.

In the eyes of the studio, though, it had created a monster: one far too boisterous to be allowed off his leash, and after Suzuki made Branded to Kill—widely recognised in retrospect as the definitive film of his career—Nikkatsu made moves to finally cut ties with the filmmaker. As Suzuki tells it, the studio’s reasoning for his firing was simple: he made movies that made no sense and made no money.

He was subsequently exiled as an outsider for the rest of his career (leading to some of his most inspired work), but his blacklisting from the Japanese film industry only bolstered Suzuki’s legend as one of the country’s greatest anti-establishment auteurs—a playful rogue with a knack for originality. Only last year Nikkatsu proudly celebrated 100 years of Seijun Suzuki with a glorious retrospective in his honour. It’s the kind of poetic irony that would have been met with a chuckle from Suzuki—fitting for noir’s greatest mischief-maker.