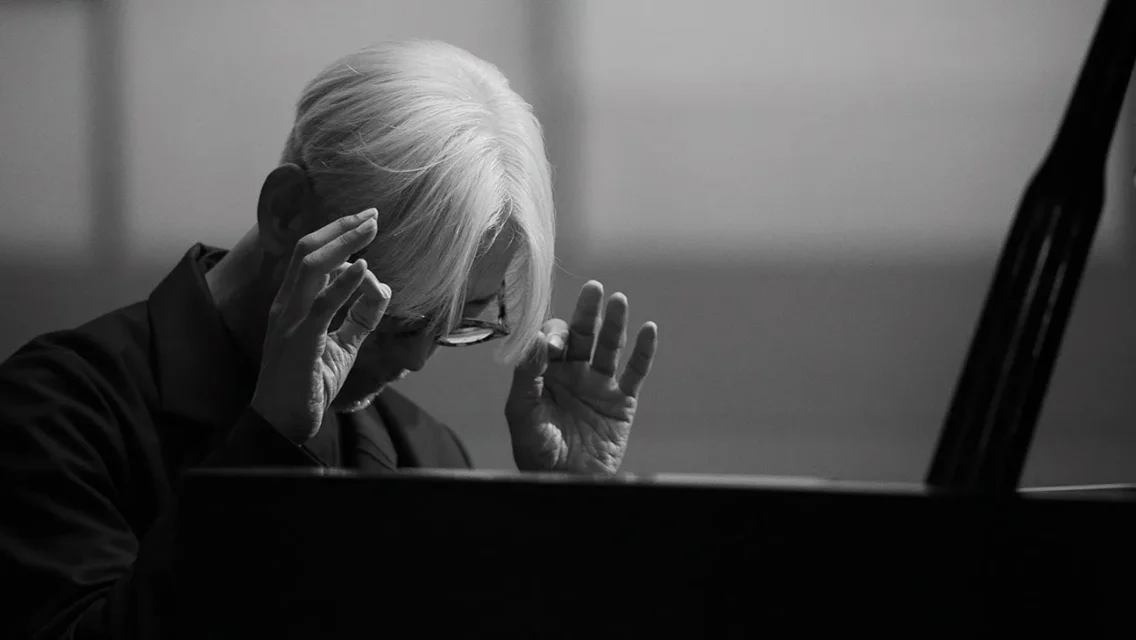

From our view, it’s an almost empty room, with the exception of a man, a grand piano, and a floating arm lamp to illuminate him as he creates. The man is composer, pianist and visionary Ryuichi Sakamoto, and the film is Opus. Directed by his son, Neo Sora, Opus is a curtain call for the Oscar and Grammy award-winning musician, who died a year to the day of the film’s UK release. It’s a simple premise: no narration, no archive footage, no talking heads—just Sakamoto sitting at his piano performing twenty pieces that map out a constellation of his monumental career. There aren’t any title cards or timestamps, but fans of Sakamoto’s will no doubt recognise the gentle melancholia of Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence—the title track from the Nagisa Oshima film that he starred in opposite longtime friend David Bowie—or his sweeping theme from Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor, which won him an Oscar for Best Soundtrack in 1988.

Though the setup is minimal, there’s a feast of detail in Opus, from Sakamoto’s graceful hand gestures to the slight facial movements he makes as each note reaches his ear, to the reflective silence between songs. During the final act, Sora cuts to an empty chair but allows the music to play on, the keys pressing themselves as if Sakamoto’s physical body has evaporated but his spectre remains. It’s a sentiment both haunting and moving in equal measure. After the final note is played, the film doesn’t fade to black, but it cuts. Subtle choices by Sora that ring with quiet grief and finality.

Sakamoto plays every note with an unyielding resolve, as if he knows this is the last miracle he’ll ever offer the world, and sometimes that thought seems, even for him, too much to bare. “I need a break”, he says. “This is tough. I’m pushing myself.” It’s one of the only lines of dialogue in the movie, and no sooner have the words left his tongue that his fingers begin tapping at the keys again. As painful as it is to see the master wrestling with his own fragility, you can’t help but smile watching him leap, seconds later, into a complex composition that he makes look utterly effortless.

To mark the release of Opus, Neo Sora joined us to discuss capturing his father’s final concert through a cinematic lens.

———

Luke Georgiades: You’ve filmed many of Sakamoto’s performances over the years. Was there a particular pressure knowing this might be the final one?

Neo Sora: The fact that it was the final performance is something that we only learn in hindsight. He was getting weaker, so the possibility was always there, but in the moment I wasn’t necessarily thinking of the fatality of it all. The pressure came more from the fact that it’s a film that I’m responsible for, and the practicalities of working with a crew and working within the limitations of the space and budget.

LG: As an audience member I did feel like this was a tribute to his legacy. At what point during the making of the movie does that come into play for you?

NS: The ending, with the piano that plays itself, is something I decided on before he passed away. So, on some level, I knew that this would be the final time the world would see him play. It’s an interesting question that I fail to give a sufficient emotional answer to because…it’s like how it’s not necessarily at a funeral that you cry. it could be weeks or months or years later that the grief manifests itself, that you’re reminded of your loss, sometimes at the most random, mundane of moments. During the making of the film I didn’t necessarily feel that emotional about his potential passing, but there was one particular moment in the mic where the sound engineer was showing me the difference between stereo 5.1 and Atmos…and that really got to me. The Atmos sounds so much more clearer, like he was in the room playing in front of us. It really made me feel his absence. At that point it was like a week after he had passed. That was the moment where it sunk in that he was gone.

LG: What made you feel compelled to start working on the film so soon after his passing, and how much of your grief were you allowing to seep into the film?

NS: When I was editing the film, I was definitely thinking about the idea that the music remains even after our physical bodies leave this plane. So some of those choices…cutting to the empty chair, for example, were definitely in relation to those ideas. They weren’t solely emotional, they were also intellectual ideas. I always loved the image of the piano playing itself—the midi piano. It felt like a ghostly thing, like one of those hotel pianos where the keys are pressing themselves. I’ve always been fascinated by that. I always knew that would be the ending.

LG: Can you tell me about how you approached the passage of time in the movie?

NS: The idea came from Sakamoto himself. Sakamoto was always deeply concerned with the concept of time; whether it was linear, and whether it existed at all. To the point where he made a pseudo-opera called Time. He was curious about it. He loved the quote by Paul Bowles from The Sheltering Sky, that goes: “how many more times will I see the full moon rise?” He was thinking about that a lot. So it was important for me, too. All of the decisions that I tried to make with the film were to enhance his original vision for the filming of this performance. He wanted it to be black and white, he wanted twenty songs, he wanted just him and the piano, and It was my job to fulfil that. Where I could be creative was with the lighting, which is what I used to depict the passage of time during the day, to create that arc of the moon and the sun rising and setting. We depicted it with stage lights, with the lamp that was beside him, and the black and white grading allowed that aspect of the lighting to come through even more deeply.

LG: How far back did Sakamoto’s obsession with time go?

NS: Sakamoto was a man of philosophy and science, as much as the arts. I’m sure he was obsessed with it throughout his life, but especially in the final decade or so. He obsessed with how time progresses, and how different organisms and beings experience time in the world. Those kinds of questions were always swirling around his mind. If you looked at his bookshelf, you would see books that, in one way or another, had to do with time, with post-it notes and bookmarks scattered throughout them.

LG: There are beautiful moments between the music. It seems important to you to show him at his most vulnerable here.

NS: There was a lot of vulnerability that we decided not to show, but yes, the imperfections are something that I know people will latch on to. They’re the only moments in the film that show his failing self, his vulnerable self, and I wanted to keep those in because I think that’s what musicians do. They experiment, and they fail, but their failure leads to beauty. There’s an improvised section in the song Bibo No Aozora, and there’s a moment in the movie where he’s playing it and he messes up—but that failure unhooks a limitation he had about making the song work. It unleashes and liberates him. And now he’s able to go on these strange tangents, where he starts exploring these dissonant chord progressions, and they don’t work, so he starts exploring these other progressions, and he’s discovering new things as he’s playing. It’s integral to the process of how music is made. It jolts the mind of the audience, too, because it’s so unexpected.

LG: Is there a certain spirit that Sakamoto wanted audiences to take away from the movie?

NS: There’s some things he really cared about towards the end of his life. He was interested in the moments where sound progresses into non-sound. One of the reasons in the film that he plays a lot slower than usual is due to his failing health, but also because he’s really enjoying listening to the moments where the vibrations and the sounds melt into nothingness, into silence. Something I take away from the film is how much he enjoys listening to that himself. Towards the end of his life he became obsessed with listening to the decay of sounds. I don’t know if he wanted to show that of himself, but he trusted me and the team enough that he allowed himself to show that side of himself in front of the camera. There’s always a push and pull for performers, between making sure all the songs are practised and perfect, but the more you practise the more boring it gets.

It got to a point in his life where he hated playing Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, and there was a moment in his career where he refused to play it. But then there was a concert he attended, it was someone like Peter Gabriel or another really popular folk singer, and they refused to play their most popular song. He felt frustrated about that, and then he realised that this is the kind of thing that fans want. So after that point he began to bring Merry Christmas back into his repertoire again. As a performer, he had to strike this balance between having to play something and having to make sure it’s perfect, but also discovering new things inside your own music, and letting the music live as its own organism. He was enjoying discovering the sounds he was producing in the film itself. It was fun watching him have fun like that, despite it all.

LG: As his son, you have ties to this project in a way that is totally unique to you. How much of this process has been for you, how much has been for the audience, and how much has been for your father?

NS: A little bit of all of those things. My goal was to try and be a conduit as best as possible. What he wanted to do was to leave behind a concert, just as he would have done it in front of audience members. He chose to make it into a film so more people could access that final concert. As a filmmaker, I had to do my best to give the audience a little more to latch onto, in terms of his story. People asked why I didn’t include interviews, or cutaways with backstories, and those kinds of choices may have been kinder to audience members who weren’t as familiar with him, but I also feel that sometimes well-defined stories can actually cloud the art you’re seeing. This is something that painters and visual artists work with. Imagine the following: you get two children to draw a house. The first draws a square with a triangle on top of it—a representation of a house. But the second child goes to his home, looks at his house, and tries to draw as best as possible what he’s looking at. Sometimes, to me, the better artist is the second child, who tries to look at the house for what it is. It might be an imperfect representation of houses, but he’s trying to capture something that’s real in front of his eyes, that isn’t clouded by the concept of “houseness.” It’s not a symbol. It’s real.

The film is similar. I could have given you information to understand who he is, and what each song meant to him in his life. But actually, maybe understanding those things actually clouds the purity of what’s being presented in front of you. There’s a lot that you can get out of just watching. That’s the beauty of music. It’s unlike an essay or writing where people use these conceptual words in order to elicit an emotion. It’s an extremely direct medium of delivering emotions to another human being. I didn’t want to get in the way of that.

LG: Is there a Sakamoto piece that moves you the most?

NS: I’m moved the most by the songs of his that seem the least dramatic, and the least emotional. There are two songs in the film that I think are particularly that way. One is called Opus. And the other one is called Aubade. They’re these repetitive songs that don’t necessarily wrench your heart, but there’s something about how quotidian the songs are that touch me, because it reminds me that life will go on, and the day continues.