Chris Cotonou: Can you remember your earliest memories of learning about Robbie Robertson and his music?

Martin Scorsese: It was The Band. I heard them for the first time in 1968, an extraordinary year for music in general. And in the midst of it all, there was Music from Big Pink.

I heard it for the first time with my friends, and we were all amazed. Everything about it was astonishing, from the cover art to that incredible aggregate sound. We couldn’t stop talking about it, because we’d never heard a sound like that before, or songwriting like that. The music seemed to come from out of the deep American past, and further back to the ancient ballads and legends that had crossed the ocean, but at the same time it sounded absolutely contemporary. And there were characters in the songs. On The Weight, which moved me deeply, one voice would take a verse, then another, then another… but it was all the same person.

The voices… Rick Danko and Richard Manuel and Levon Helm took the lead vocals, Robbie Robertson did harmonies, and they sounded so human, so intimate, nothing smooth or professional-sounding about them. Levon Helm’s drumming was as great as his singing—the poet Jim Carroll once said that Levon was the only drummer who could make you cry, and I know exactly what he meant. Garth Hudson’s organ took the music to a whole other realm. It was almost celestial. And it was spiritual without being explicit about it. It reflected the spiritual longing that was there for my generation, that was pulling a lot of people to the East. It spoke to that. And, of course, there was Robbie’s guitar—every note, every small inflection mattered.

The music conjured up images of the America of the 19th century, and the quest for salvation. Now, we look at the movement west in a different way, but it wasn’t just material gain that everyone was looking for—some, but not all. Some people were looking for a new home of the spirit. Would they find it? What were they going to find out there? That feeling is there in The Band’s music. So, hearing the music on that first record, for the first time, was overwhelming, an experience I’ll never forget.

CC: Why do you think Robbie was such a natural when making music for cinema? What made his music so ‘filmic’?

MS: I think it gets back to this question of characters. The songs are dramas, with characters, and they come alive the way that movies do. The Weight—you can see it as you listen to it. It’s the same with The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down—“Virgil Kane is the name and I served on the Danville train…” The songs set a scene the way you set a scene in a movie: “Corn in the fields, listen to the rice when the wind blows across the water, king harvest has surely come” or “Now when the rumor comes to your town it grows and grows, where it started no one knows.” And the singing and the music animate the lyrics, give them mystery, a depth of vision… So yes, Robbie’s music was “filmic” right from the start. With The Band and after The Band.

We worked so closely that we wound up sharing a house for two years, and giving each other ‘classes’ in music and in cinema.

Martin Scorsese on Robbie Robertson.

CC: What was the glue, or particular commonality, that held you both together as friends—especially considering your very different backgrounds?

MS: Our friendship began with The Last Waltz, and that was an extremely intense, concentrated experience. We were working together to create something new—not just a record of a concert, but a real movie in which the characters played music, and shared the communal joy of making music. It was about the music, and about the people in the process of making it together. We worked so closely that we wound up sharing a house for two years, and giving each other ‘classes’ in music and in cinema. When we came out of it, there was a bond between us, and it was unbreakable.

CC: Is there a moment you shared with Robbie that you treasure deepest? Or perhaps that says a lot about his great character or yours?

MS: It’s hard to isolate one moment, because our friendship spanned so many years. I could talk about his silence—he would just sit, quietly, in a room filled with people, and listen. He would be thinking, but you never knew what he was thinking. I could also talk about his storytelling. He told stories and you would be hanging on every word: it was like listening to an ancient mariner, or a griot. Or, I could talk about the way he gave me what I needed, whether it was the right song for the closing of Raging Bull or the right music and rhythm for the gushing oil at the beginning of Killers. Or, I could talk about his laconic humor. He came out to Oklahoma when we were shooting and the temperature was all over 100 degrees for days on end. “Pretty hot, isn’t it?” I said. Robbie: “It puts hell to shame.”

CC: In Bob Dylan’s When I Paint My Masterpiece (also sung by The Band) we hear about the chase for a creative masterpiece. What do you think Robbie saw as his masterpiece?

MS: I don’t think he saw anything in particular as his masterpiece. In truth, I don’t really know any artist who does think of their own work in that way. It’s a different perspective. It’s the kind of evaluation that can only come from the outside. Actually, the song seems to me to be about the great dream we all have of putting it all together, so that everything is smooth sailing from here on in. It’s a beautiful dream that we all dream together.

CC: What do you think is the work that you consider the most special through Robbie’s career—including in your own collaborations?

MS: Well, the music he made with The Band is a real high point in American music, American art. And I have to say that his music for The Irishman and Killers are two of the most beautiful scores ever created for movies. They are actual cinematic elements, deep in the bloodstream of both pictures.

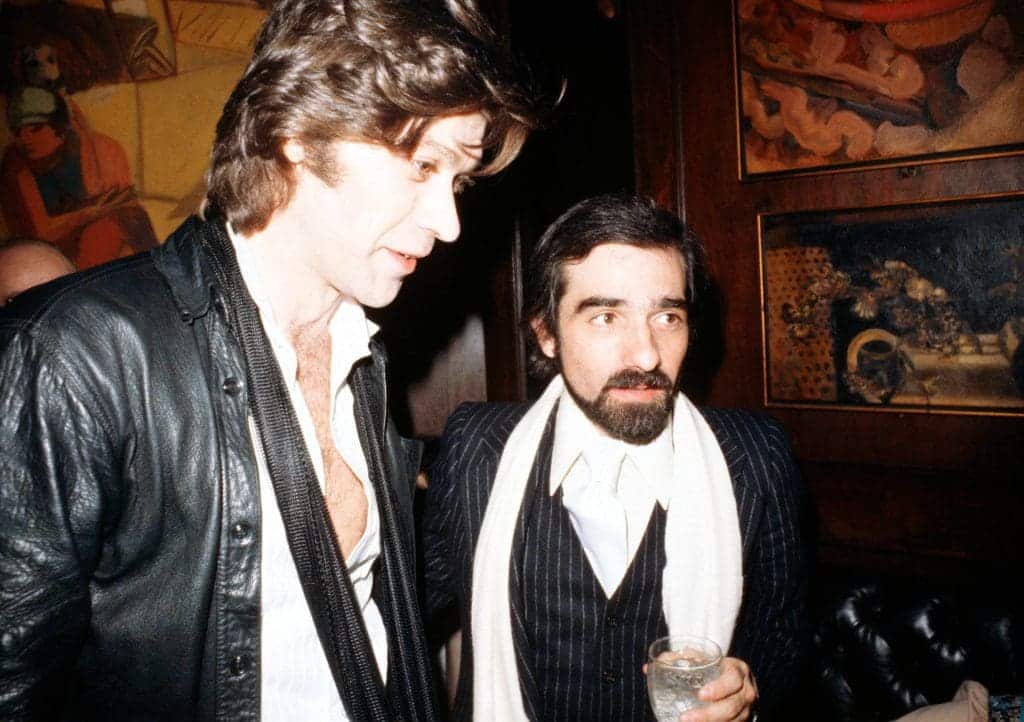

Robbie Robertson with Martin Scorsese. 1978. By Richard E. Aaron.

CC: Robbie’s music in Killers of the Flower Moon is such an epic work. Is there a process you use to articulate the mood or atmosphere you want from your scores, or did you mostly just leave it to Robbie to interpret?

MS: I gave him suggestions. Over the years, we learned how to communicate with each other. So for instance, on Silence, I told him I wanted to hear the sound of silence. He gave it to me by using the sounds of cicadas, recorded at different times of year in different parts of the world, and then treating them in the studio. He gave me what I wanted: the sound of silence. And for Killers, we used the same cicadas and Robbie slowed them down and created something otherworldly for the opening scene, the burial of the pipe—a low ambient hum that sounds like it’s coming out of the earth: it could be music, it could be a message… For the oil scene, I said that I wanted a gusher of sound, and that’s what he gave me with that rhythm; that “wolf call” guitar, as he called it. For the scene where Lily gets into Leo’s cab, I told him I wanted something “dangerous and fleshy.” He gave me something dangerous and fleshy. He delivered.

CC: Was there a particular thing that motivated Robbie throughout his life to create?

MS: Isn’t that always a mystery? You can say that of everyone who creates art at that level. People who write books about him could probably identify this or that event in his life, but really… It’s a mystery. Always.

Featured image: Martin Scorsese and Robbie Robertson attend the 31st Cannes International Film Festival for the premiere of The Last Waltz. 1978

You might also like: “Making Sport White”: Paul Schrader on Taxi Driver