What happens when a baby’s brain is put into the skull of a fully grown woman? That is the central concept of Poor Things, Yorgos Lanthimos’s 2024 period comedy about Bella Baxter, a 25 year-old woman of the late Victorian era. She is the experiment of Godwin ‘God’ Baxter, a surgeon and mad scientist who finds the pregnant corpse of a woman called Victoria Blessington following a suicide. Godwin resurrects her with the unborn baby’s brain and raises her as his daughter. Initially childlike, emotionally stunted, unruly and lustful, Bella travels around the world and learns to be a ‘proper’ human who stands against social injustice.

Whilst reading the book on which Lanthimos’ movie is based (Alasdair Gray’s 1992 Poor Things), I started to wonder if the plot might not be so simple—if you can call it that. On the internet and particularly amongst Gen-Z audiences, a popular reading of the film since its release has been that Bella is autistic, that she doesn’t understand social cues and thus does not control herself in the way a woman should “in polite society” (as Bella reminds herself with a wrist slap). Whilst this reading is definitely interesting and enlightening, I feel like it is anachronistic. In Victorian Britain, mental health had not yet been ‘invented’ let alone more nuanced understandings of neurodivergence.

What the Victorians were absolute experts at, however, was hysteria. In Gray’s original text, I was struck by the references to La Salpêtrière, the infamous psychiatric hospital in Paris where the doctor Jean-Martin Charcot treated (mainly female) hysterics. “[We] visited Professor Charcot at the Salpêtrière, and how hard he tried to hypnotise me? At last I pretended he had done it, because I did not want him to feel silly in front of his huge audience of adoring students,” Bella writes in her letter to God from Paris. This link got me thinking about the ‘wandering womb,’ a definition for hysteria first elaborated in Ancient Greece. The belief was that female madness and pathology was caused by movements of the uterus (“a living thing inside another living thing,” wrote the physician Arateus in 200 AD), so spreading strange symptoms throughout the body.

Emma Stone in Poor Things © 2023 Searchlight Pictures.

In the book, which contains a letter from (an alive-and-kicking) Victoria Blessington at the very end, she refutes the entire baby-brain narrative, calling it out as a macho Frankenstein fantasy on the behalf of the narrator. This move (which is not exercised by Lanthimos) throws the whole book into question. Yet I still see Bella Baxter/Victoria Blessington as a metaphor for the wandering womb. Formerly suicidal and depressed— conditions deemed by Victorian society as lunacy—her unborn baby has migrated to her head in some sense, with her faculties and spirit traumatised. It goes without saying that hysteria was just another way to infantilize women and downgrade their pain.

Bella experiences all the ‘sugar and violence’ of the world, eating oysters and pastel de nata, chugging spirits, dancing, having (a lot of) sex and making friends. There is a great sense of release, as if all her past pain is being healed in these carnal and cerebral pursuits.

In Lanthimos’s film adaptation, Bella’s status as a hysteric is more easily legible. Defined in general by a lack of control and rationality, the symptoms of hysteria include emotional outbursts, loss of language, contorted movements, insomnia, erratic nature and sexually forward behaviour. All these attributes are present in Emma Stone’s performance of Bella with her jaunty, convulsive corporeal movements and Robbie Ryan’s cinematography which at times directly recall the famous photographs of Charcot’s patients. In the film’s first half, when Bella discovers masturbation, the black and white images compartmentalise sections of her body in the same way as those medical portraits. Her face wears the same expression as that in Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa; the twitches of her legs registering pain and pleasure. Yet rather than allow Bella privacy, McCandless documents Bella’s every development whilst Lanthimos’s now trademark fish-eye lens, adds to a feeling of incarceration and surveillance.

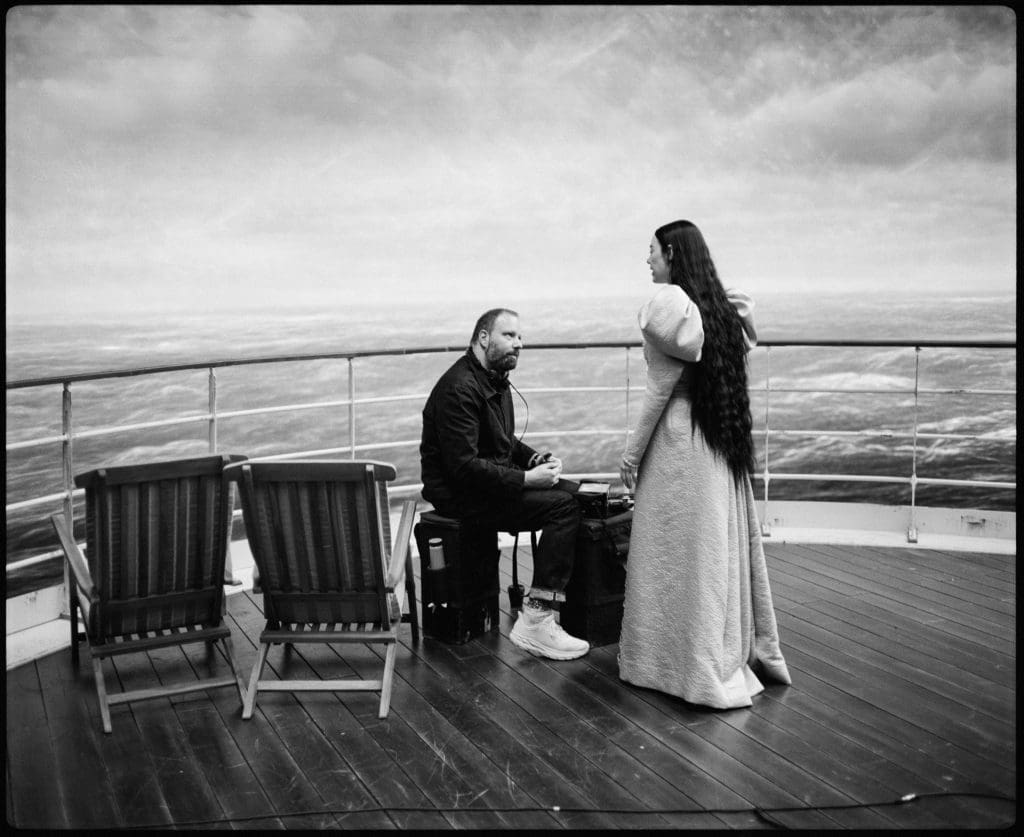

Yorgos Lanthimos and Emma Stone on the set of Poor Things. Photo by Atsushi Nishijima © 2023 Searchlight Pictures.

Bella becomes a wandering womb more literally. It is when she is allowed to roam (rather than be holed up, Madwoman in the Attic-style) that Bella is allowed to flourish, and is ‘cured’ as I see it, of her hysterical tendencies. She experiences all the “sugar and violence” of the world, eating oysters and pastel de nata (“with gusto”), chugging spirits, dancing, listening to music, having (a lot of) sex, making friends, finding employment and learning new ideas. There is a great sense of release, as if all her past pain is being healed in these carnal and cerebral pursuits. The gendering of female hysteria finds further reprieve in the characterisation of her lover Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo). Lustful, angry and self-flagellating, he is driven to insanity by Bella, and ends up locked up in a padded room in Paris. Perhaps it’s La Salpêtrière.

It is no surprise that with Poor Things, Lanthimos—godfather of ‘neurotic’ cinema— has made another film about insanity and how society controls it. Dogtooth, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, The Favorite and The Lobster all explore this theme. The auteur is currently working on an adaptation of Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, whose nameless heroine might be Bella’s millennial cousin. Beautiful, misanthropic and world-weary, she medicates herself with a long list of downers, sedatives and sleeping pills in her pursuit of a pure, dreamless, uninterrupted sleep. Unlike Bella, she is abstinent and taciturn, only leaving her room to get coffee from the bodega. I cannot wait to see how Lanthimos brings her to the screen.