Since releasing his debut feature Greek Pete in 2009, Andrew Haigh has made a name for himself as a visionary on the British film scene. Known for bringing tender, often queer, romances to the big screen, his latest, All of Us Strangers, might be his most emotionally resounding work to date. Starring Andrew Scott and Paul Mescal (a pairing made in fanfic heaven), the film follows Adam (Scott), a reserved queer screenwriter living in a barren London high-rise, whose lonely existence is brightened by a chance meeting with Harry (Mescal), a younger, carefree tenant in his building. Simultaneously, Adam begins visiting his childhood home and reconnecting with his parents (Claire Foy and Jamie Bell), who he’s been mysteriously estranged from for years. As the relationship between them develops and past traumas are brought to the surface, Adams’ grip on reality starts to unravel.

During our conversation at London’s Soho Hotel, Haigh refers to the pain inherent in nostalgia, and watching the mystery of All of Us Strangers unfold, it becomes clear that memory is the lifeblood of this delirious narrative: memories of our lived experiences, and memories that never existed at all; illusory what-ifs conjured up by our subconscious as gateways to long-buried traumas.

As such, while not wholly autobiographical, All of Us Strangers is steeped in Haigh’s own personal history. The childhood home where Adam visits his parents in the film is the very same that Haigh grew up in, while The Royal Vauxhall Tavern, the queer nightclub frequented by our two protagonists, was a constant place of community and comfort for the director as a young queer man in the 1990s and 00s.

Below, Haigh discusses the themes of All of Us Strangers, the difference between how British and American culture process emotion, and why sex scenes are integral to the cinematic medium.

Luke Georgiades: The film is an adaptation of Taichi Yamada’s novel Strangers, which is a ghost story but doesn’t feature any queerness. Why did you think these two stories would go hand in hand?

Andrew Haigh: I’d wanted to tell a story for a long time about how romantic love and familial love are somehow attached and connected, and how in queer relationships that can be really complicated by the fact that a lot of queer people, especially from a certain generation, had a difficult relationship with both their queerness and their family.

Then I read the book. There’s no queerness in the original story, but I thought that it might be the perfect text to link those two themes together, because I do feel that the grief from losing someone and the grief when you’ve had some kind of traumatic experience in your life—such as coming to terms with your sexuality—are linked with each other. To do it through a ghost story made the most sense to me.

LG: Queer friends of mine who watched the film have told me that it reminded them of their own mortality. Is that something that you feel is specific to the queer experience in a way?

AH: That’s true. A lot of my friends, who are my age and queer, are obsessed with their mortality. I grew up coming to terms with my sexuality as people were dying of aids, and we were being traumatised by the horror of that. It truly felt like our futures would not be possible. We felt like we would not be able to be gay and be in a relationship without putting our lives on the line. So we’re very in tune with thinking about ideas of mortality. But also, I’m at a certain age – I’m fifty now –and it’s when you start to lose people. And through those losses you start to look back on your life and reflect on other relationships you’ve lost, not necessarily through death, but through time, and you become more in tune with the transient nature of things.

LG: What kind of emotions did shooting this film in your childhood home bring out of you?

AH: Nostalgia is painful. My parents were loving but it was a complicated childhood, they split up when I was young. So going back into the house was difficult, but interesting. I lived there until I was seven, and I hadn’t been back for forty-odd years, but the memories were as vivid as they were when I lived them. I could feel it all again— the rooms, and the ghosts they contained. I remembered sitting in corners, where the Christmas trees were, and where my bed was. I had to bring those memories back to life when we shot there, and it was a cathartic experience, but I had to separate myself from them to some degree. You have to, you’ve got a whole crew in there.

LG: There’s such a strong musical presence in the movie. How personal were the music choices to you?

AH: I knew from the moment I began writing the script what the needle drops would be and where they would appear in the movie. I had a playlist that I listened to as I was writing. I bought the Frankie Goes To Hollywood album at the age of eleven and I would listen to The Power of Love constantly in my bedroom, not knowing why I loved it so much. Now that I’m in my late forties, I realise it was a question, it was a longing, and now that it’s in the movie it’s an answer to that longing I had as a child. The power of pop music is that it can articulate things that we can’t express—pop songs are euphoric and melancholic and they express our emotions in a way that is obvious, and deeply cathartic because of that.

LG: Although you focus tightly on this relationship between Andrew and Paul, it feels like the movie is still expressing the importance of community, and being able to express what you need from someone, and what you can give to someone, before it’s too late to do so.

AH: That’s what the purpose of the film is to me. The idea that truly getting to know, and truly allowing yourself to be known, is the key to this journey we’re all on in the world. Being compassionate and kind to people—that is the nature of love. Regardless of your situation, the essence of being alive is struggling. We all feel very alone at times, we feel confused and traumatised, but to know each other is to soften the impact of those moments. I wanted to be quite sincere about that, to not be embarrassed by it. Let’s face it, British people aren’t very good at being honest about how we feel, and it’s not easy to say “I love you” to somebody. Sometimes you don’t need to. The expression is the key, not the words. I wanted the film to explore that.

LG: Talking about the Britishness of it all, do you think this is a story that could be easily translated to American experiences of the same themes?

AH: The film seems to have been embraced in America, so thankfully, what the film is saying is speaking to them too, but there is such specificity between British and US culture, not just in terms of queer culture but generally. I spent a long time in America, and we all speak the same language, but it’s a very different experience. When [British people] say the word “melancholy”, there’s a sweet joyfulness to what it means—we embrace it, and sometimes actively search for it—but when Americans talk of melancholy, it means depression. There’s something in the British spirit that enjoys elements of sadness, and we understand things in a certain way, whereas in America it’s about the search for happiness. We love to revel in the bittersweet. We like it when it rains. We complain about it, but we sort of love it.

When British people say the word “melancholy”, there’s a sweet joyfulness to what it means—we embrace it, and sometimes actively search for it—but when Americans talk of melancholy, it means depression. There’s something in the British spirit that enjoys elements of sadness, and we understand things in a certain way, whereas in America it’s about the search for happiness.

LG: A lot of your projects revolving around the queer experience, from Looking to Weekend to All of Us Strangers, have that essential queer nightclub scene, and I wonder how integral that specific aspect of queer culture has been for you?

AH: In the late 1990s and early noughties I would go to Duckie’s all the time. And the Vauxhall, where we shot the nightclub scene in All of Us Strangers. I’d go to those clubs three times a week sometimes. I can’t speak on how it is now, but for queer people back then, clubbing was absolutely essential and synonymous with this idea of safety that we didn’t feel out in the world. We went to those clubs to be surrounded by people who they felt like were the same as them. I’ve always wanted to represent that feeling. But there’s two sides to it—it’s both liberating and terrifying. In this film it starts off great but makes it clear that if you’re not careful, it can overtake you. Sometimes it isn’t actually giving you the things you think it’s going to give you, it can actually make you feel isolated too. The queer community has had to deal with dichotomy too.

LG: Were you aware when you cast Andrew and Paul that you were about to set the internet on fire?

AH: [Laughs] I knew when I first cast them that the internet was going to find them super hot. I knew they’d love these two together. And I wanted that. I wanted it to be intimate and tender, but I also wanted it to be sexy. I wanted it to be hot.

LG: There’s also been a back and forth between largely Gen-Z film fans and older film fans about whether sex scenes are necessary in any film. Have you heard about this?

AH: No, but that sounds terrifying to me. To not have sex scenes in films means you don’t want films to reflect life, so that argument makes absolutely no sense to me. As a filmmaker you’re trying to reflect life. Look, if you don’t ever have sex then fine, don’t put it into a film, but people do have sexually intimate relationships.Sex has to be integral to cinema. What I think they’re right about is if the sex scenes don’t mean anything in the film, they shouldn’t be there. If they’re there just for titillation, it’s pointless to me. A sex scene has to show some kind of development between characters, and if they do that, then they are really important.

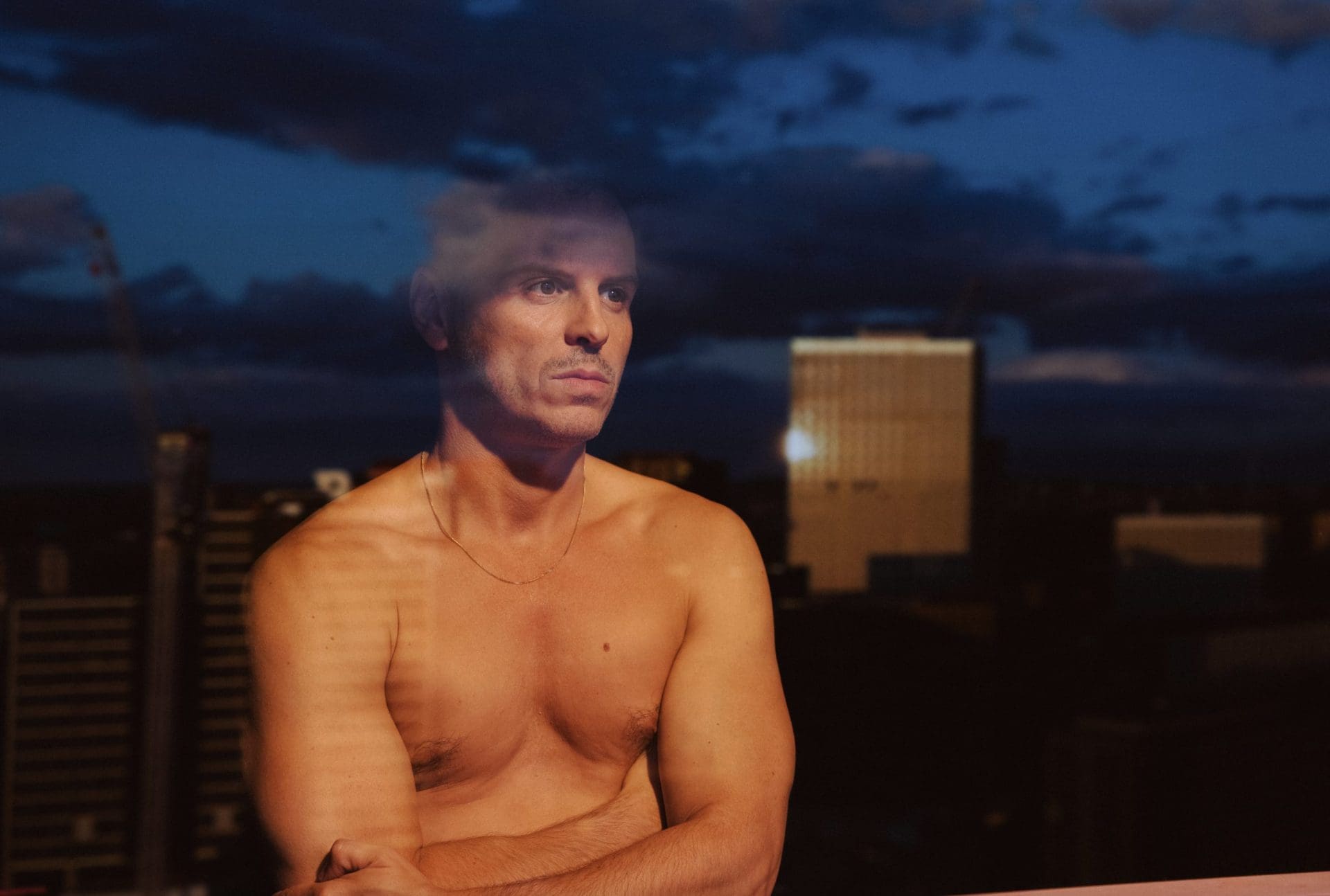

LG: The other prominent location in the film is that towering high-rise that overlooks the city—why was it important to the themes here to have Adam looking over the city constantly?

AH: From the beginning I wanted everything that the audience saw to be a manifestation of his psychological state. There’s an oddness to the tower. There’s no one else living there, but sometimes when you live in a tower block, sometimes you do feel like you’re the only person on that block. I wanted it to always be playing with what’s real and what may not be real. He’s always looking at something. There’s something calling him from the distance, it’s within reach but he can’t quite close that distance or engage with it.

LG: Without going too deep into spoiler territory, let’s touch on the ending for a moment.

AH: I don’t like a simplified emotion at the end of a film. There’s a world in which you could imagine this story happening and it would have a very happy ending. There were conversations about that ending, but it was keeping everything too grounded. And I needed it to become something transcendent. Growing up, I never thought that the love that I might have for another man could ever be possible.o I wanted to end this film with a grand statement on what that love could mean, but not just my own personal relationship with queer love, but the love I feel for my parents, and the people that I’ve lost throughout my life. My grandmother’s been dead for thirty years, but I still feel love for her with the same intensity, maybe even more so. It’s a clumsy cliche, but stars die and we see the light for millions of years. Have you seen Altered States by Ken Russell? Batshit ending, magnificent and cheesy, but there’s something truthful about it. I approached the ending here with the same energy. I want you to feel discombobulated in order to feel more of an alchemy of emotion, because that is what grief and love bring out of us. But it hopefully brings a realisation of just how immense that love was, and still is.