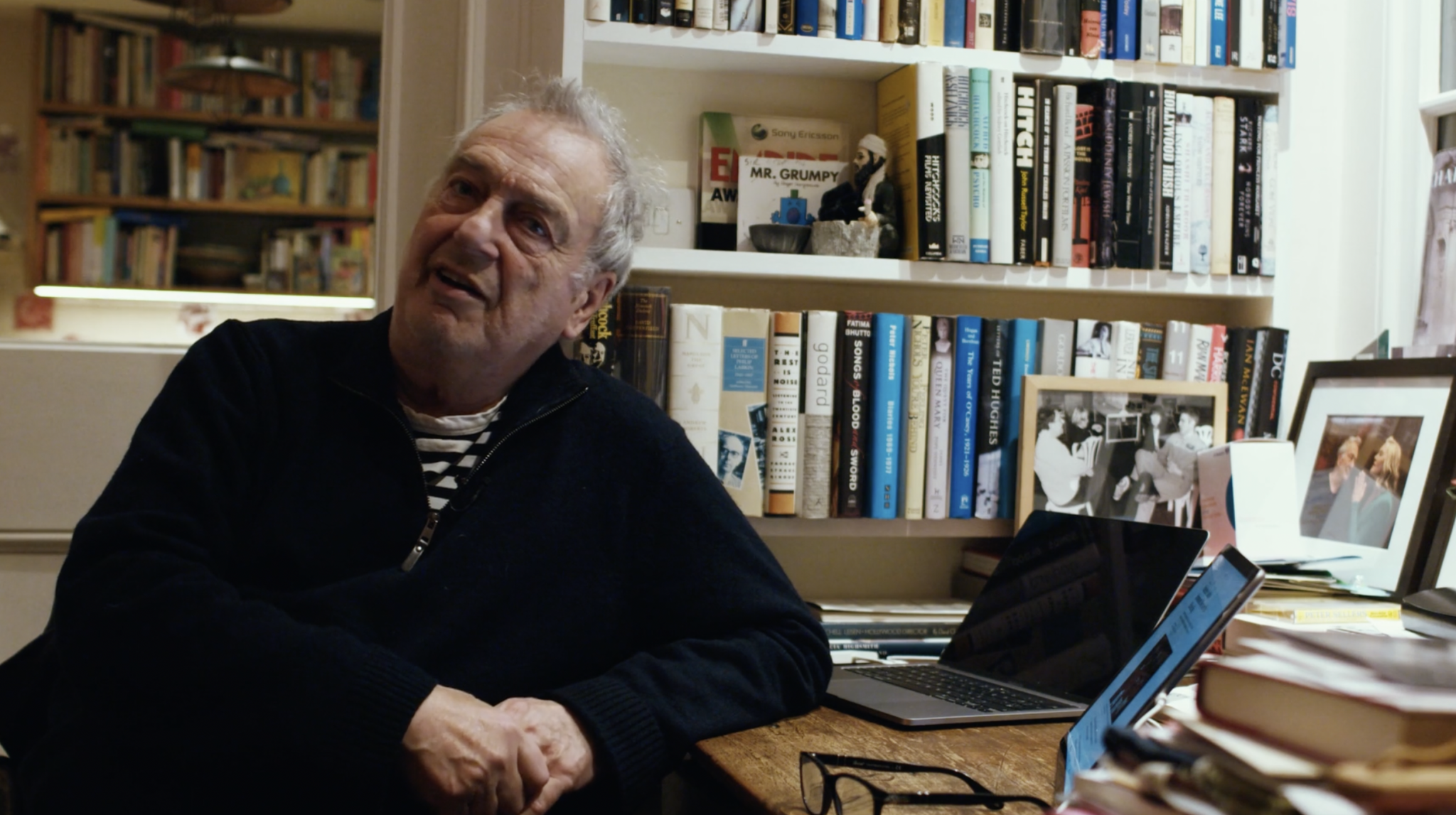

I attended my first Cannes in 1971, when I was 21, as the companion of Susan Delfont, the daughter of impresario and financier Bernard Delfont, whose film The Go Between was in competition. I drove there in a Mini, paying my way with borrowed money and credit cards. I had continually loved French films since I was young because my father, the film director Ralph Thomas, used to screen them for us at home, and I was particularly taken by L’Atalante by Jean Vigo and generally my perceived sophistication of French cinema. I saw on that first visit that Cannes would be something very important to me in my career. I wanted to be a part of it.

Since then, I’ve felt I have a magnet pulling me there. I’ve done the drive to Cannes every year since I first fell in love with it, an annual pilgrimage, only missing an edition when my son was born or when one of my films has been shooting. I was next in Cannes in 1975 for Brother Can You Spare A Dime. I was the editor and the film played in Critics Week. We took the reels down in the back of the car and spent our time trying to raise money for the next film. By then I was beginning to understand Cannes: it was a place where cinema could breathe.

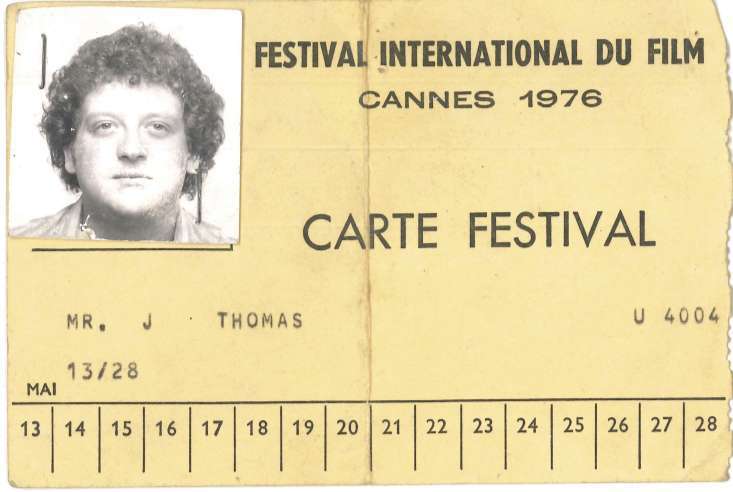

In 1976, I went there with the first film I produced – Mad Dog Morgan – directed by Philippe Mora. Next, I made a film with the great Polish filmmaker Jerzy Skolimowski, The Shout. It starred Alan Bates, John Hurt and Susannah York and had a fascinating plot where a traveller by the name of Crossley forces himself upon a musician and his wife in a lonely part of Devon. He uses the aboriginal magic he has learned to displace his host. It was a rare item, an English film seen through the eyes of a foreigner, and beautifully shot by Mike Molloy. It went on to win the Grand Prix de Jury at Cannes in 1978, my first taste of success at the festival, and I’m still working with Skolimowski today.

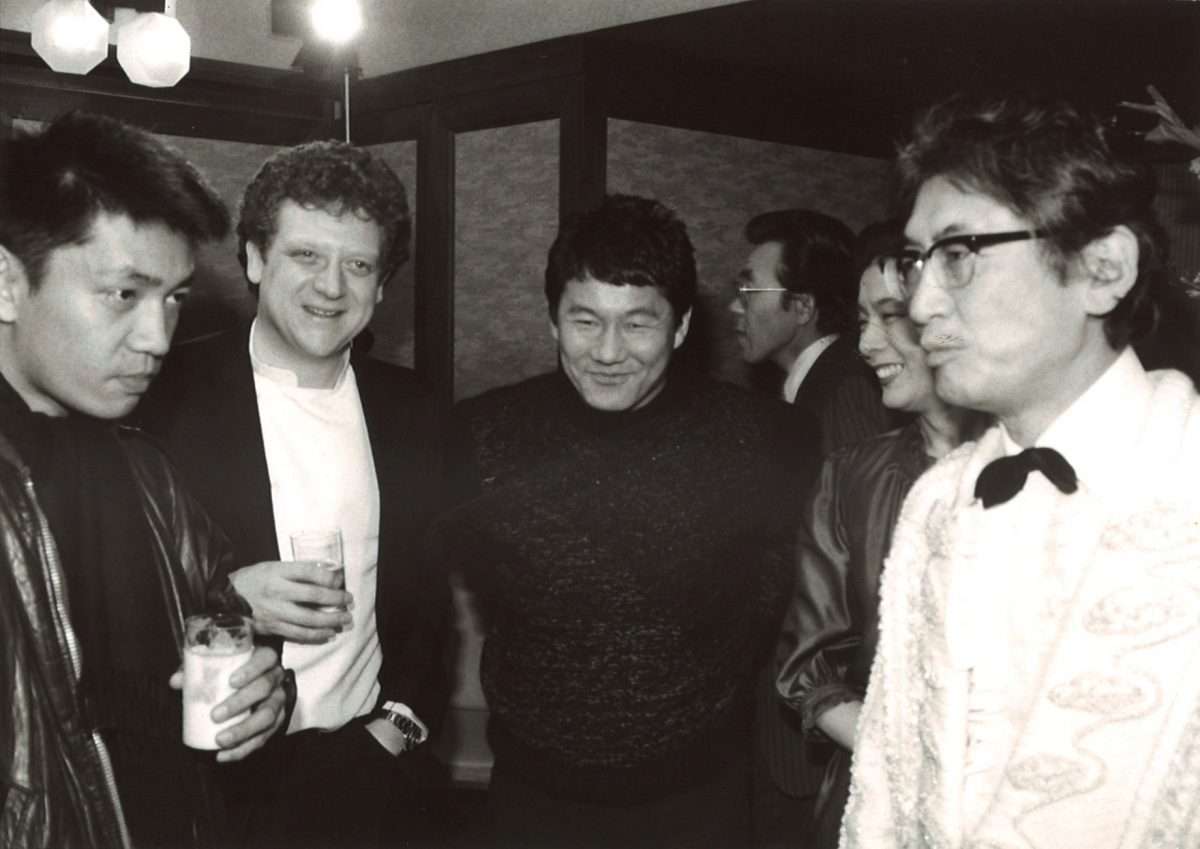

It’s been over 40 years since I met Nagisa Ōshima at Cannes. I had seen many of Ōshima’s films, The Ceremony, that I found so compelling, and I was amazed by Empire of the Senses and Boy, and I had a great love of Japanese cinema. When I attended Cannes with The Shout, at the dinner after the prize-giving I met Ōshima. We exchanged business cards. He talked to me about a screenplay which was to become Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence.

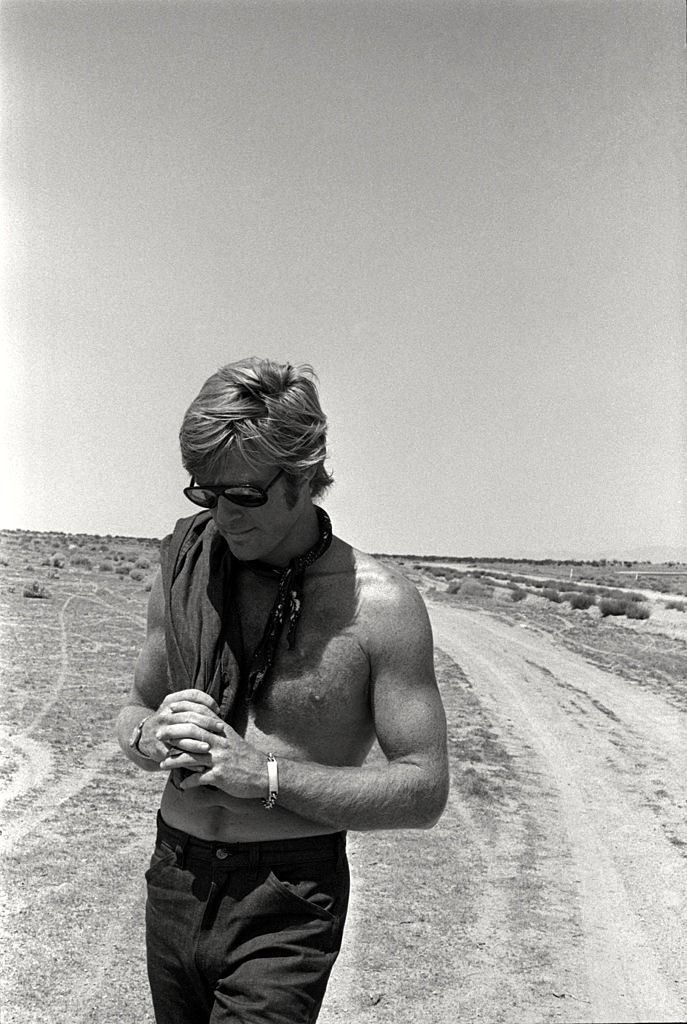

In 1980, I went to Tokyo and saw Ōshima again, and we talked more about Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, and then began working with the British screenwriter Paul Mayersberg. We started on the casting. Initially, Ōshima wanted Robert Redford as Jack Celliers as his idea was a blonde god, and then he alighted on David Bowie. Bowie immediately wanted to work with Ōshima and it was a brave thing for him to do. I brought the great Australian actor, Jack Thompson, who I had worked with previously. Ōshima populated the film with unusual cult figures from Tokyo like musician Ryuichi Sakamoto, comedian Beat Kitano and Plastic Elvis.

We were looking to shoot in Okinawa, but we couldn’t find the money. New Zealand offered up a desert island, Rarotonga, which was a tax haven. This stood in for Malaysia and everything was shot in New Zealand: it was a true collaboration between cultures.

Unlike many directors, Ōshima left the door open for something else to come through, including the scene where Bowie mimes smoking and shaving. Ōshima shot it and left it in the movie. With the scene where Bowie eats the flowers, Bowie didn’t want to eat them at first. Ōshima said: “I’ll eat the flowers”, and then half-an-hour later, Bowie agreed to eat them. Tom Conti was amazing; a great actor. He spoke no Japanese; Kitano spoke no English: it was all learned phonetically. It was because of this experience that Kitano became a director.

We sent the rushes back to Tokyo via Fiji, which took three weeks. The camera jammed during the scene where David Bowie embraces Ryuichi Sakamoto and kisses him on the cheek and we only had 40 seconds of footage, so it had to be step-printed – hence why it’s in slow-motion. People commented on the poetry of this moment, when in fact it was the random quality of art.

Ōshima asked Ryuichi Sakamoto to compose the score, and Ryuichi said “How can I do this?” He had never composed a score before. Ōshima told him that he wanted him to do it like Captain Yonoi, the character he played, and somehow this incredible music came out of Ryuichi, who I feel is a genius.

Ōshima had planned scenes with a lot of extras for one day. How he finished shooting with that schedule and amount of extras before the end of the day, I was incredulous, but he said he had no trouble at all, that he had shot everything he needed to. During the edit, he was equally fast, especially given that he had accumulated few takes or extra material, unlike Kurosawa, who wanted to make more monumental films.

At Cannes in 1983, the reception of the film was incredible and helped a lot by its French distributor, Gerard Lebovici. David Bowie came, as did Sir Lawrence van der Post. He was an amazing man, and the story came from his own experiences. Celliers was loosely based on someone he had met in a POW camp. The last day at Cannes, the film team were together having lunch on Carlton Terrace when someone ran to the table and said that the Japanese film had won the Palme d’Or. We all leapt up and hugged each other and celebrated.

The NHK cameras immediately came! But it was a false rumour, because though it was awarded to a Japanese film, it was to Imamura for The Ballad of Narayama. But it was great, and the festival had a wonderful experience with the film. I recently rewatched it after it was restored to make a beautiful new DCP, and it’s one of the films of my filmography as a producer that I’m most proud of, for its high moral qualities and for everything that happened during and around the film. It is the only war film I’ve ever done, and I find it moving especially with all that is happening today. The last words of the film about the futility of war ring true. I think of it as the anti Bridge Over The River Kwai. I think of it as a love story: as a feeling of man’s love for man.

My relationship with Japanese filmmakers and Cannes has since continued with Takashi Miike, the prolific and controversial auteur who has an unmatched versatility. Amongst other competition titles with Miike, in 2011 we bought Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai to Cannes, which was the first 3D film to screen in the Palais. But I’m skipping ahead.

In 1984, I was fortunate enough to have the late, great legend and producer Hercules Bellville join me at my production company. Hercules was a highly cultivated human and connoisseur of art and people, and we had formed the closest of friendships. He accompanied me on my drive to Cannes for many years. He was a witty and exacting companion, and every journey was meticulously researched with a movement order. He would make sure that we visited only the most interesting hangouts and out-of-the-way cultural sites, all marked with pen on a map, before Google Maps. He would wear a beret especially for the trip, and shout gruffly at passers-by for directions in his perfect French with an accentuated English accent.

Hercules was a committed internationalist and he had a powerful film intelligence. At Cannes, he was in his element and active from dawn till dawn. Here, he could meet with his formidable little black book and commandeer filmmakers from all corners of the globe into meetings, where he would immediately make everyone feel at ease. He was beloved at Cannes, where his relationships ran deep with all working at the festival. He would arrive on the red steps wearing a wooden bow-tie with extra Orchestre tickets in his pockets that no-one else would have been able to procure. Hercules was an irreplaceable friend and colleague, and never missed more greatly than at Cannes.

In 1986, Bernardo Bertolucci and I bought the first reel of The Last Emperor to Cannes showing the Emperor’s coronation, and it was broadcast live at the opening ceremony, which was a wonderful gift. I’ve been with Bernardo at Cannes many times.

I’ve been eaten up and spat out on the Croisette a couple of times. I sat on the feisty 1987 Competition jury, which controversially awarded the Palme d’Or to Maurice Pialat’s Under The Sun Of Satan, which was booed in the Palais. My fellow jurors with chair Yves Montand included Elem Klimov, Theo Angelopoulos, my friend Skolimowski and Norman Mailer, amongst others. The reaction was very bad. People were very passionate about it. But not one of those jury members was a pushover. Klimov was very tough.

In 1996, I found myself in another storm when David Cronenberg’s Crash caused a great controversy. We had received a call from Gilles Jacob, informing us of our competition slot. The film first screened on the morning of 16th May 1996, and it all kicked off. We’d heard that jury president Francis Ford Coppola didn’t like the film from the morning screening. We had a heated press conference that afternoon, which UK critic Alexander Walker stormed out of. He was waving a newspaper, shouting from the back, ‘Travesty! It’s outrageous!’ before describing the film as “beyond the bounds of depravity” in the headline of his column in the London Evening Standard. Walker and a coterie of UK critics saw an opportunity for an incredible story involving J.G. Ballard, Cronenberg and myself. I think I may have been chair of the British Film Institute at the time. But Crash must have had its advocates and still took the Jury Special Prize at Cannes, for “audacity, daring and originality”, with a public abstention from Coppola. In contrast to Crash, the same year we had Bertolucci’s Stealing Beauty in competition, which everyone loved.

The fierce reaction to The Brave directed by Johnny Depp was another challenging moment. But the highs have far outweighed the lows, from getting a film fully financed at the stroke of a pen when Francis Bouygues signed a $40M cheque for Bernardo Bertolucci’s Little Buddha on the spot, to being president of the Un Certain Regard jury in 2004, which was hard work but I enjoyed it immensely.

What some people still don’t understand about the festival is that it’s first and foremost a French film festival in the same way that Berlin is a German film festival and Venice is an Italian film festival. Each festival reflects its own national culture and what cinema means to that culture. France has very specific tastes and has very specific qualities and ideas about cinema.

As much as it is a celebration of art and aesthetics, Cannes also hosts its fair share of fakes. Cutting through the noise is a craft. You have to be disciplined. There are many casualties in Cannes: it’s a very easy place to party too hard.

Ultimately, it is the movies which are most memorable. There’s no more powerful screening in the world than a Palais screening. I remember seeing Breaking The Waves and just being absolutely blown away by the film. Dead Man was another. Giant figures such as [Akira] Kurosawa and [Jean-Luc] Godard are among the many auteurs that I remember fondly at Cannes, and [Quentin] Tarantino is amongst those who are still capable of delivering that great cinematic event at the festival, where for all its trappings, the importance and magic still endure. I feel that Thierry Frémaux has successfully balanced the heritage of its past while bringing the festival into the present, with an eye to the future.

Of course, I’ve missed out many high points, and directors I’ve bought to Cannes, including Nicolas Roeg, Stephen Frears, Terry Gilliam, Jim Jarmusch, Takeshi Kitano, Wim Wenders, Matteo Garrone, Khyentse Norbu, Souleymane Cissé and David Mackenzie.

If you’re in the business, you’ve got to be at Cannes, and you need to respect the real affection for rigorousness and selectivity about films, which is uniquely Cannes. It’s something unattainable. You can’t buy it.