The first time I saw it I had been with Marion, my daughter, who at the time was young enough to need constant attention. I’d walked past the fountain with Marion in my arms and she had turned her mother’s head away with her little fists so I’d barely seen it. I remember because afterwards Mark had said, wow did you see the mercury fountain, it was great, and I’d said, a little curtly, hardly, because I was holding our daughter, meaning, why don’t you hold her sometimes you know she’d like to get to know her daddy too, but of course I didn’t say that. He’d been offended and had suggested I was spoilt and didn’t appreciate the gift he’d given me of coming to Barcelona on holiday. Then he’d taken off with the euro cash purse and the key to our holiday apartment, leaving Marion and me with a packet of organic baby snack puffs (Spanish version) in the bottom of Marion’s buggy.

Mark liked to take me to galleries, museums and other cultural points of interest and then leave me with Marion who was really a needy child, so that I would see little of the pictures or exhibits. Then he would tell me about them at great length, over elaborate tasting menus, insinuating always what a fool I’d been to miss them, while I lactated into my bra and tasted nothing. Although, after Mark took off in anger that day I never did get to hear about the mercury fountain. Still, something about it stayed with me. Flowing metal, it mesmerised me. Over the years I’d found myself meditating, at times of stress, upon my little memory of the fountain. When work was bad or during Mark’s episodes, as he called them, I would absent myself from the world and imagine silver trickles, slow, shiny, deathly, flowing, forever. It calmed me. Of course, Marion is twenty-two now and terribly grown-up, living with her friend Emerald who, I remember from school had pen-sets that made Marion jealous. I left Mark nine years ago and in this, the tenth year of our separation I am taking sabbatical from my work at the university and I am returning alone to all the cities that Mark chose for us to visit.

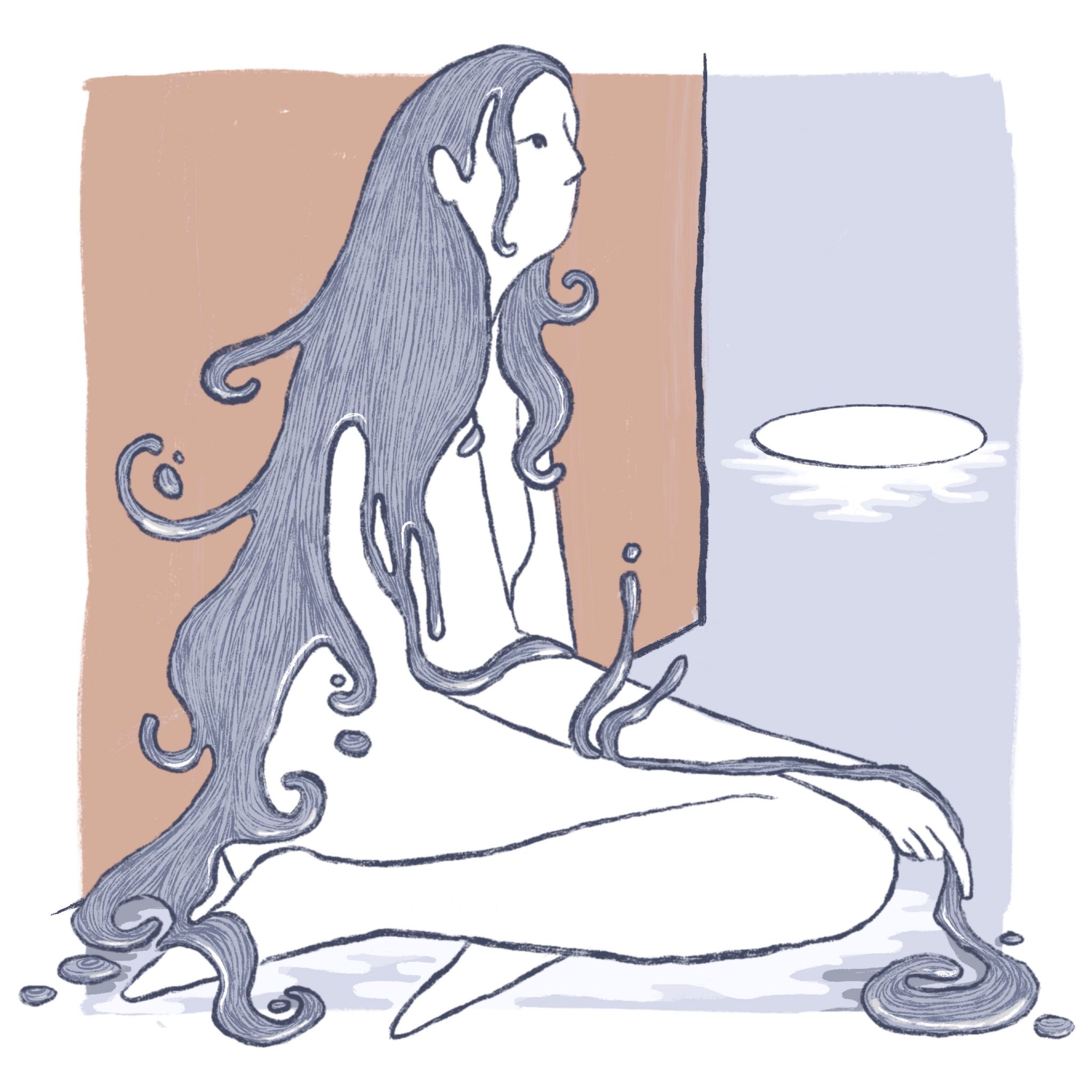

I am travelling south-wards through the European spring. By the time I reach Barcelona in late April, it is hot, dry and dazzling. I take the funicular railway to visit the Fundació Joan Miró, where I know I will find the mercury fountain. This time, when I reach it, I stop for a long time. It is dangerous and beautiful, sealed in a glass box because of the poisonous mercury. The glass is so thick that the fountain’s stream and pump seem silent. Rivulets of mercury make long, licking, shiny tongues on the sculpture’s matt black metal. Against the black the mercury is darker, thicker than I’d imagined. The tongues splash, strange and slow into a viscous pool below. A label beside the fountain reads ‘Mercury Fountain, 1937. Alexander Calder. Sheet metal, rod, wire, pitch, paint, and mercury, with pumping mechanism and basin.’ It tells me that the cut-out word, ‘Almadén’, hung over the fountain’s pool, is for the mercury mining town of that name where miners resisted Franco’s forces. I read the information, but it runs off me. It is the shine and the poison alone that fascinates me. Mercury, a broken thermometer, silver beads scattered on our mother’s kitchen floor, shafts of sunlight, squatting, toddler, curious. Touch! Me touch! Little fingers, shiny rolling beads, round and whole even when they broke and mother’s voice, no love, that’s not for touching, that’s dangerous my love, we need to tidy it up, wait with your sister, my love, take this, taste of Calpol, milk. The shiny beads skidded and glided when our mother brushed them. Look at the waater, I never saaaw such shiny waaater says an American voice, the English sharp to my ears through the Catalan-Spanish jumble. Mother’s kitchen floor falls away, melting into the mirror-skin metal. I consider correcting the American tourists but it has been hours since I’ve spoken and my breath has reached a soft regularity I do not wish to disrupt with speech. I stand a while longer, watching. Other tourists seem to have the same difficulty moving on from the fountain. There is something heady about its slithering gleam, something noxious that charms and fixes us, even while the poisonous fumes are shut away in their glass case. It is like a mad, confined animal, its powers taken from it.

I take a photograph for Marion. And for you, my sister, I write the following:

Do you remember when we’d share a bed when you were twenty-one and I was twenty-three and every night we’d lie, open-eyed in darkness that was a great everything, a great open everything in the way it would shrink and grow so quickly around our eyes, like our wild excitement and wild fear for our futures, our gorgeous, mysterious futures, our Maria singing on her way to the Captain’s house, our Esther Greenwood, starving at the crotch of her green fig tree with her fat, winking, wrinkling, plopping figs.

Like Icarus, we told ourselves, we must be careful not to fly too close to the sun of excitement, because, we understood, from such wild, flapping heights we could fall hard and fast. Do you remember that night we woke up with our faces close against each other’s and our arms entangled and you laughed, maybe dreaming of something funny, and I said ‘what’, and then we both fell back to sleep.

Icarus rose to feathered stars, like a burning Phoenix, and a silver crinkle flickered and became a boy, a real boy who flew and died, the headlines promising his silver, shimmering name, for I hear a silver crinkle in the ‘ix’, and the River part of his name turns the silver crinkle to a shimmering stream. He is quicksilver. River Phoenix, Immortal quicksilver boy, dead and wasted then born again, young and tender forever, he never chose, never lost, never won, never-never-land. Sister, I want you to run your palm over mine again, give me some skin, like they do in the movie.

At my rented flat I look up ‘Mercury poisoning’ and ‘River Phoenix’. Symptoms of mercury poisoning are: weakness, numbness in the hands and feet, skin rashes, poor co-ordination, memory loss, trouble hearing, trouble speaking. There was an ancient ruler of Egypt, I read, who liked to be rocked to sleep, floating on a bath filled with mercury. Numb, mindless and senseless, some peaceful sleep. River Phoenix, I read, was barely educated, could hardly read or write. He was carried from The Viper as he died and they say he was like liquid between the men who held him.

I sleep deeply and dream of River’s liquid body.

I have a day left in the city and should probably go to see something else, the National Gallery of Catalonian Art perhaps, or one of the Gaudí houses. Make the most of the day, you know. But I am a thing obsessed. The mercury fountain pulls me like a tide, back up the city’s leafy hill, back to that silvery blood. I am the first in the gallery. I walk straight through to the fountain and sit with my back to the wall opposite. Again, I am mesmerised. Today, the fountain’s beauty seems vaster, bleaker than it seemed yesterday. Today the beauty puts nothing in my mind, no associations, no memories. I am lulled into vacant, silvery peace. My legs and feet grow numb from the pressure of the wall on my lower back. Tourists step over my numb legs and feet as they pass, as though I am not there. In the fountain’s endless movement there is blissful stillness. Nothingness even, pure nothing, relief.

I am a mute, silver lady.

After some hours I realise I am hungry and I feel my phone vibrate. It is Marion. She has ‘hearted’ the photograph I sent of the fountain and has sent one back of her and Emerald holding complicated drinks and smiling. She has also sent two pink heart emojis and one sunshine one. She is a good daughter. We are approaching each other. She looks forward in anticipation while, from ahead of her, I look backwards in knowledge, and sometimes also in regret. I see her looking forward and I wonder, does she see me looking backward, seeing her? Or, is her line of vision like a stranger’s in the street, passing and never meeting my own? My hunger is causing my attention to drift. I am wasting precious moments with my fountain, but I must find something to eat. In the café they are selling sandwiches wrapped in foil. I choose one and eat it as fast as I can, resentful of every bite that draws me away. Afterwards, I return to my squat against the gallery wall. Apart from my fingers, which twist the ball of foil from my sandwich between them, I am still. My fidgeting hands unfurl the foil and smooth it on the cold floor. They rip strips of flattened foil and wrap them around my fingers so their tips are foil-capped, hard and taloned. I avert my gaze from the fountain to admire my new silver claws. I understand what I need to do. I tear the foil and wrap a thick band of it around my wrist. I wet my lips and my cheeks so that the torn, jagged pieces of silver foil stick to my skin. I cut and dab disks of the stuff onto my eye-lids, so that when I blink I am an open-eyed silver beast of a thing. I sit there, silent, blinking, shining.

The sun has passed through the fountain’s casement and the shadows have switched sides. The gallery guards are asking tourists to leave, which they do in dazed, obedient droves. But I am a mute, silver lady. Perhaps they will not notice me, perhaps they will not ask me to leave. The sounds of the guards’ heels are different now that the visitors’ clothes and skins are gone, no longer absorbing the clip clop clip clop towards me. Do not ask me to leave, I am a mute, silver lady, let me stay. I will not move, so the baffled guards lift me gently under my arms, but my body is limp and heavy, too difficult to move. They try once and I slump down the gallery wall. Twice and a piece of foil falls from my eyes and catches the blue flash from the guard’s radio. When the guards try a third time, four of them now, two under each arm, a surge of energy rushes through the room and the guards fall backwards. My arms dissolve. They are falling loose into shimmering drops, like my shoulders, my eyes from their sockets, my silvering hair. I turn into mercury and scatter all over the floor.

Rosa Picard is a young writer from London. She was recently selected for The Stinging Fly‘s six-month fiction course, and this is the first appearance of her work in print. When not writing, you’ll find Rosa practicing handstands, or distractedly admiring the trees from the window of the office where she works in publishing.