In the latest documentary from Laura Poitras explores the life of Seymour Hersch, a journalist who has devoted his life to uncovering the violence at the heart of America.

In 1968, 6000 sheep dropped dead in the fittingly named ‘Skull Valley’ in Utah. They were the victims of nerve agent poisoning, as a result of testing at the nearby Dugway Proving Ground—a chemical and nuclear testing ground kept secret by the American government.

We learn about this incident—elaborated with archival imagery—at the opening of Cover-Up, the latest documentary from Laura Poitras about the investigative journalist Seymour M. Hersch, a Pulitzer-prize winning journalist who has dedicated a career to uncovering the dark truths and corruptions of American government and corporations. “There is a history of America that is very hard to write,” says Hersch, interviewed at his desk, surrounded by piles of yellow legal pads and boxes of old files and notes. The sheep, whilst numerous, are only the tip of an iceberg of what he will also uncover.

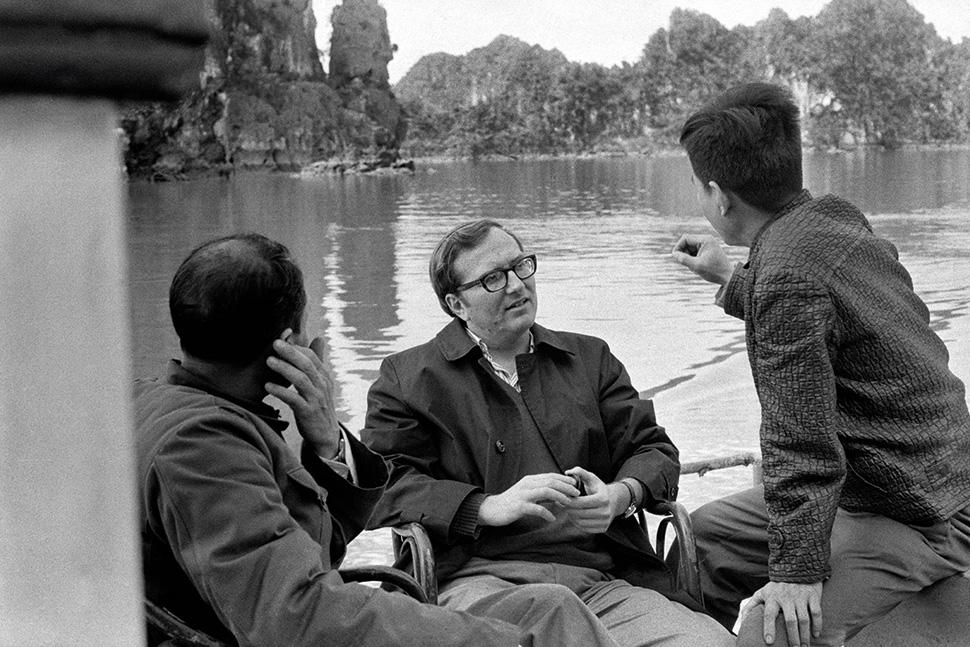

This is familiar thematic terrain for Poitras’s whose previous documentary, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, about artist Nan Goldin’s attempts to expose the orchestrated nature of the opioid crisis by Purdue Pharma’s Sackler family. Her 2016 documentary Risk focused on WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. But Hersch is perhaps her most prolific subject, and explores the idea of concealment at a systemic, macro level—his journalistic discoveries include the My Lai massacres, whereby American soldiers gunned down civilians, including babies, in Vietnam, behaviours which turned out to be just “another day in Vietnam”, America’s involvement in the assassination of foreign leaders they deemed a threat as well as reporting on Watergate and Iraq, where he broke stories on American soldiers carrying out torture in their prisons. Each story is different, but the behaviour is the same—a “culture of violence” that is pervasive in American life.

Fasincatingly, Hersch also explores how journalism itself acts as a kind of concealment. He recalls how, as a young journalist, he would go to the Pentagon everyday and hoards of young journalists would write-up their 500 word reports with little interrogation of the facts they were being served. Hersch, who went to work at The New York Times, himself became outraged when the newspaper were resistant to him reporting on corporate scandals (the New York Times, are after all, also part of corporate America, he notes).

Beyond the stories he himself tells, Hersch is a fascinating subject matter to take the layers off, who admits early on he feels slightly uneasy in front of the camera, wary of their attempts to “psychoanalyze” him. But it’s hard to resist. We learn that Hersch was born to Jewish refugee parents in a household where secrecy was pervasive. The Holocaust, which they had survived, was never spoken about. After his father became sick, Hersch took over his laundry business (his “pizzazz” and ability to speak to people made him the best candidate of his siblings). In a David Copperfield-esque turn of events, a teacher at his night school noticed his intelligence and sent him to the University of Chicago. He later became a police reporter in the city, observing that the mobs and the police had a lot in common.

Poitras first asked Hersch to be the subject of a documentary in 2005, and said he would when he was “ready”. 20 years later, he agreed on the basis that Mark Obenhaus (Poitras’s co-director), who Hersch has collaborated with before, is brought on. There is an irony in his own distrust of being documented. Hersch is clearly a deeply emotional (he is prone to depression and also anger) but also paranoid man and, as the documentary goes on he panics that he has given away ‘too much’, after sharing boxes of notes with the documentary makers, and promptly calls it a day.

Yet this is an inspiring portrait of an aging investigative journalist who is engaged in his career with the same youthful energy he has always been (today he is even on Substack). The documentary is occasionally broken up by the loud trill of his iPhone, from sources who are calling him, getting out his fresh notepad from a battered leather briefcase. On a couple of occasions we watch his phone calls with a source who is giving him information about the Israeli army’s activities in Gaza, the fact that the IDF are more aware of targeting civilians than they publicly admit. This is where the moral weight of the documentary is felt most keenly. Stories will always be covered up, and we will always need people like Hersch to uncover them.