If you’ve never been to the Toronto International Film Festival, here’s the secret: it doesn’t begin when the projectors start to whirl. It begins in the line-up. September air still clinging to the last days of summer, hot coffees in hand, strangers compare notes on what they’ve seen and what they’re chasing next.

What’s most special about Toronto—which I’ve been attending since 1985—is that this buzz belongs as much to the audience as it does to the stars. It’s why TIFF, even at fifty, is still the “people’s festival.” Cannes has yachts. Venice has gondolas. Sundance has powder. Toronto has the queue—and everything that comes with it: access, anticipation, discovery.

In honour of TIFF’s 50 years creating great audience experiences, here are of my treasured moments from the early years of the fest, along with a look some of this year’s highlights.

My first TIFF screening was in 1985, with the opening of Death of a Salesman. When I arrived as a neophyte festival-goer, there were no tickets available, as they had sold out long ago. But just after the lights went down, a kind festival volunteer waved me in, and suddenly I was seated as Dustin Hoffman himself walked onstage. The lights dropped. TIFF wasn’t just a festival anymore; it was a brush with cinema’s greats.

Richard Marquand, Jagged Edge (1985)

That same year, Yorkville—the area of Toronto at the heart of film festival—was alive with film-going buzz as I joined a massive line for Richard Marquand’s Jagged Edge. Fortunately my “I Want it All” festival pass (still the best-named pass I’ve ever had) slid me up to the front of the queue and the front of the theatre. Inside, the cast and crew filled the stage. Then the curtain opened and a razor-sharp thriller unspooled that I knew nothing about. That’s TIFF at its purest: you walk in blind, you walk out buzzing, knowing you’ve just seen something you’ll be bragging about for weeks.

Not every TIFF moment is magic. Opening night ’86, Leonard Shein—newly imported from Vancouver’s festival—strode out and declared, “Welcome to my festival.” The room recoiled. TIFF was never his. TIFF belonged to the audience. This still defines the festival today: its ownership belongs to the people in the seats.

If TIFF had a patron saint, it would be Roger Ebert. During his lifetime he came every year, wrote about Toronto with the same passion he had for Cannes, and treated our audiences like the final word. Ebert understood the truth: TIFF’s real jury was always us. Our gasps, our applause, our walkouts… they carried more weight than any critic’s star rating.

TIFF ’87. The very first screening anywhere of Rob Reiner’s The Princess Bride. From the first laugh, the room buzzed. By the credits, you could feel it—this was a story destined to endure. Monty Python colliding with a bedtime story, an audience leaving the theatre knowing they’d just witnessed a fairy tale being born. And it did the same that year—and every year—for Canadian cinema. Cronenberg, Egoyan, Rozema, Polley: local films were never filler. They stood on equal footing with the world.

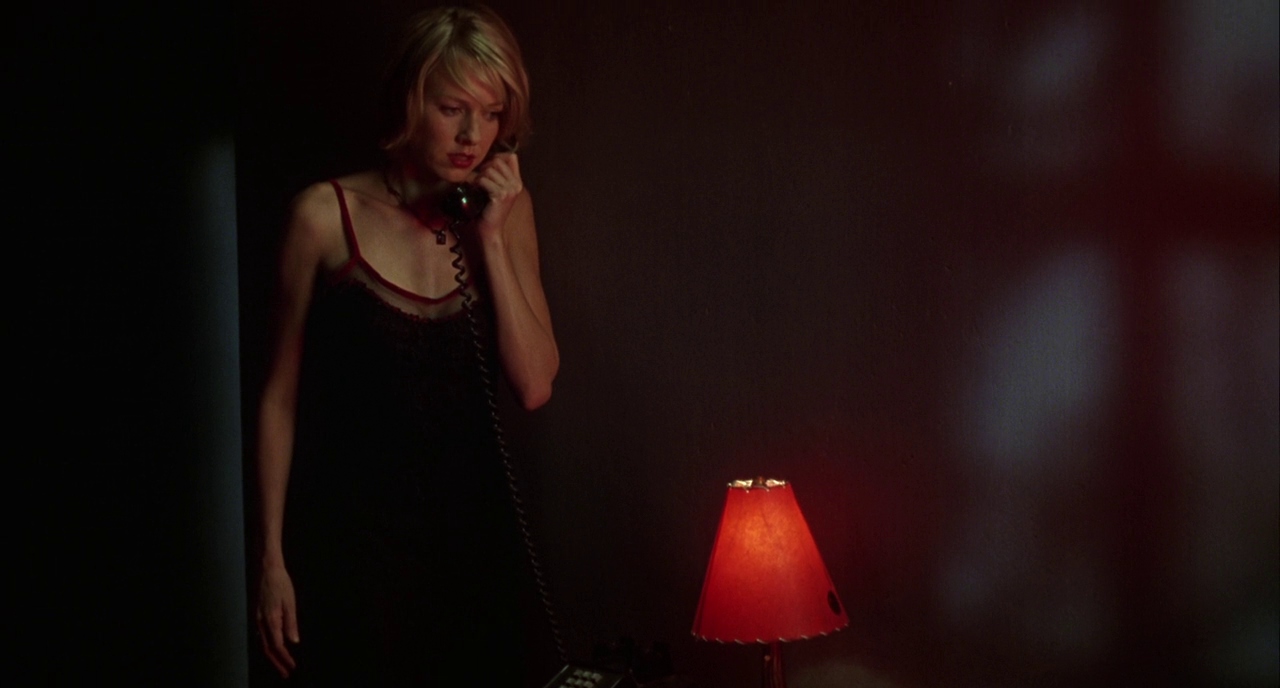

A still from Peter Greenaway’s 1989 The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover

TIFF has never been afraid of provocation. I was there in 1989 for Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover. Ten minutes in came the first walkouts. Then a steady stream. Those of us who stayed felt like we’d crossed some secret threshold. Today the film is a renowned cult classic. That’s TIFF’s gift: space for the misunderstood, the difficult, the ahead-of-its-time.

That’s TIFF’s gift: space for the misunderstood, the difficult, the ahead-of-its-time.

Jim Southcott

David Lynch, Mulholland Drive (2001)

The pinnacle for me was Lynch. Mulholland Drive, Canadian premiere. Cast in attendance, Lynch himself onstage. When Angelo Badalamenti’s score filled the room, it was like slipping into a dream you knew would never let go. TIFF isn’t just about watching films—it’s about leaning into all the film’s ‘curves’ with the rest of the unsuspecting audience.

On September 11, 2001, I sat in an early morning TIFF screening as unclear whispers circulated: “…something had happened with the World Trade Center…”. A few of the audience left immediately and the rest of us settled in for the screening. By the time the film ended, everything outside had changed. TIFF continued, subdued, haunted—a reminder that no festival is sealed from reality.

By 2010, TIFF had its permanent home in the Bell Lightbox. By 2014, King Street transformed into Festival Street. Midnight Madness kept its punk heart with films like Ong-Bak and The Raid. Hollywood leaned in. The People’s Choice Award became a reliable Oscar bellwether: Chariots of Fire, Slumdog Millionaire, The King’s Speech, 12 Years a Slave, The Fabelmans. Parties glittered, fundraisers flourished. TIFF became a global stage. And yet—the rush tickets remained. Ordinary audiences could still stumble into something life-changing.

Mary Bronstien’s If I Had Legs, I’d Kick You, playing at this year’s festival

TIFF at 50 poster

Now, in 2025, TIFF turns fifty. Aziz Ansari’s Good Fortune, David Michôd’s Christy, Alice Winocour’s Couture, Mary Bronstien’s If I Had Legs, I’d Kick You, and Chandler Kevack’s Mile End Kicks. Guillermo del Toro, Jodie Foster, Catherine O’Hara, Idris Elba among this year’s honorees. Midnight Madness still unruly at 2 AM, with all eyes on the Midnight audience’s reaction to a classic in-the-making—Bryan Fuller’s Dust Bunny!

Yes, TIFF is an industry machine. But it’s also still the place where a volunteer once snuck me into Death of a Salesman. Where a pass got me front-row for Jagged Edge. Where a Lynch score still echoes in my subconscious. At fifty, it’s still the people’s festival. The stars will come. The parties will glitter. The awards machine will hum. But the queue—that belongs to us. And as long as we’re willing to line up, TIFF will never belong to anyone else.

You can read more of Jim Southcott’s writing here on his Substack.