The south of France has long been a muse for many directors, from Pagnol to Godard. In the final of three essays on the timeless appeal of the sun-drenched Riviera, Kitty Grady considers the hyper-sexualised ascent of Bridgette Bardot in Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman (Et Dieu… crea la femme).

Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman (1956) opens with a car zooming along the coast. It is a common enough trope of books and films set in the south of France, usually portending some great, careless tragedy (Tender Is the Night, Bonjour Tristesse). This car, however, doesn’t crash.

It is the perfect opening for a film that, in many ways, is about progress and capitalism, its ceaseless movement onwards, without comeuppance or consequence. Eric Carradine (Curd Jürgens), a boom-boom businessman, is calling in to see Juliette Hardy (Brigitte Bardot), an 18-year- old orphan with an uncomfortably large libido who he is trying to seduce. This mission parallels his other plan: to build a new casino on the shores of Saint-Tropez, the town where the film is set.

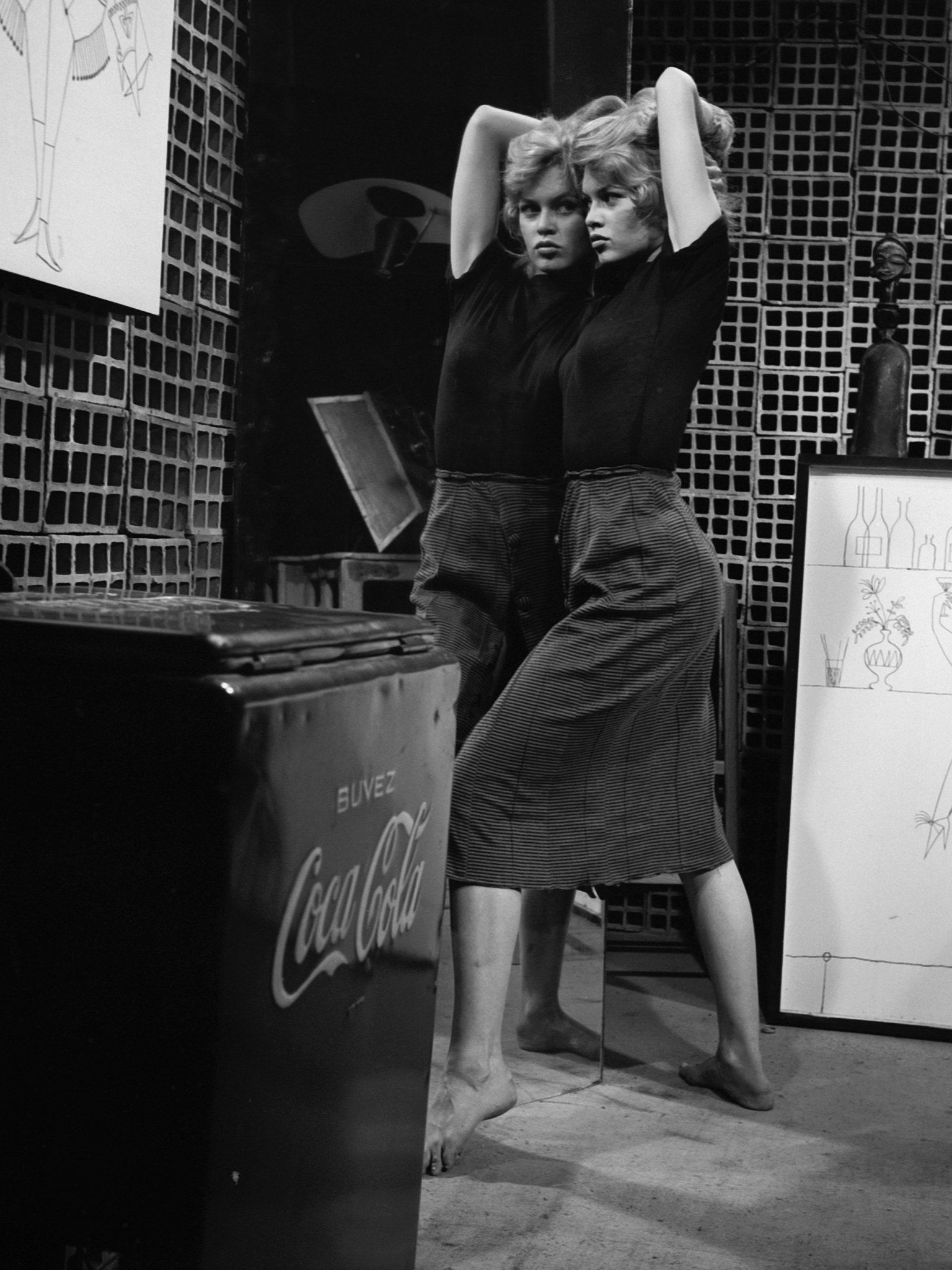

Brigitte Bardot oozes sex appeal during a scene in And God Created Woman (1956). By Roger Vadim.

It is a story of culture versus nature. Nature, of course, is feminised. Juliette is earthy, her sexuality savage (count how many times we catch her barefoot or nude—including the opening shot), and, disinterested in her bookshop job, she has a natural affinity to animals—the kitten on her bed, the birds and rabbits she frees into the field. Culture meanwhile, is male. Eric—repeatedly framed in front of models for boats and buildings—promises to buy Juliette a car, handing her a toy-sized red Simca convertible. Juliette, who prefers to travel by bike, is repeatedly pushed up against cars by men, as if to thrust her into a modernism she refuses to exist in. When her bike gets a puncture, she is forced to take the bus—a plot point that sets the wheels of the film’s story into motion.

On board she bumps into Antoine Tardieu (Christian Marquand), an old flame back in town, who it appears she truly loves. His family’s shipyard is blocking Eric’s plans for the casino. (It is not for sale). As Juliette’s increasingly erratic behaviour means she might get sent back to the orphanage she came from. With Antoine out of town, Eric perversely suggests that his younger brother Michel (Jean-Louis Trintignant) proposes to Juliette. She accepts and they marry. The family sells their shipyard for a stake in the casino.

At this point in time, Saint-Tropez— which we see in the off-season, in the lead-up to Easter—was still a quiet fishing village, with an economy built on artisanal businesses such as the Tardieu’s. The arrival of the casino marks the post-war shift for Saint-Tropez, and the south of France more broadly, to become an international tourist destination, which the (internationally successful) film helped to advertise, tempting Americans and northern Europeans like the Eve to the apple. Cut to my own trip to Saint-Tropez in 2012, and the fleet of super yachts on the harbour—I remember one, distinctly, camouflaged, as if in parody of conspicuous consumption.

But the biggest commodity of all is Bardot herself. The film launched her internationally— an overnight sensation. The title And God Created Woman is a misnomer. It suggests the orphaned Juliette’s sexuality and Bardot’s subsequent rise to fame was innate, inevitable, rather than a paternalistic fabrication of the film industry—an ‘industry plant’ in common parlance. Bardot’s lightning blonde hair is dyed, an artificiality that jars with her ‘naturalistic’ sexuality. Her animality is no more natural. “Clever film men have moulded her sex-kitten type,” read a review in the Daily Sketch. It coined the notion of the sex kitten—a hollow signifier, too neatly encapsulating Bardot’s troubling, boundless sexuality, and so allowing it to be exported across the high seas to global shores.

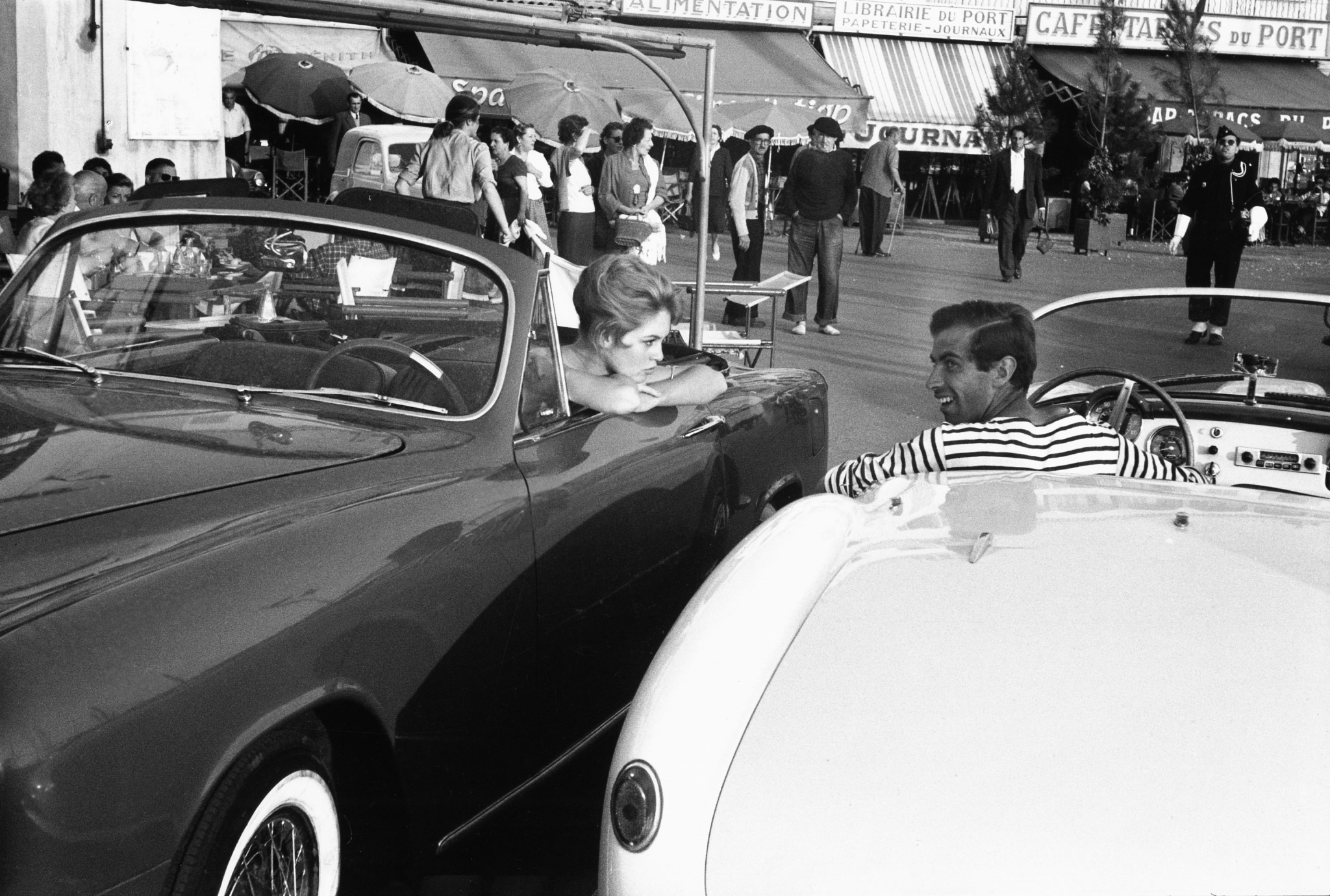

Brigitte Bardot in And God Created Woman (1956) by Roger Vadim. Photo by Edward Quinn.

Juliette does fight back against the film’s relentless forward motion. Frustrated at her marriage and acting ever more bizarrely, she takes out one of the Tardieu boats. It catches fire, and when Antoine comes to save her they jump ship and have sex on the sand. The culminating scene, in which a liberated Juliette drinks and dances to cha-cha music at the Bar des Amis (note, elsewhere, her lack of friends), is rightly labelled by some as racially insensitive, her ‘primitive’ sexuality associated with the music played by black men. But there is a fitting stubbornness in the two-step-forward, one-step-back rhythms, and the movements of a camera, which, while chopping up her body, fails to track her neatly. The scene culminates when her husband tries to shoot her but is stopped by Eric. Eric and Antoine—spooked— now seem conscious that Juliette is not there to shore up their masculinity. “That girl was made to destroy men,” says the businessman, as he drives them both off down the coast, onwards, ceaselessly to the next beautiful village, where a new tragedy awaits.