A Rabbit’s Foot columnist Haaniyah Awale Angus beats a months-long cinema slump by taking to the movies for back-to-back screenings of the Summer’s most talked-about horror films.

The date is August 16th. It’s a Friday, and London has undergone one of the many shock heat waves we pretend we’re never quite ready for. As we hurdle closer to September, the summer cinema slate remains chock full of blockbusters, reboots, indie horrors and maybe even an Oscar contender (if they ever find themselves interested in romantic comedies again.) This is also the day that I embarked on what many of my friends called an unnecessary pursuit: heading to my local cinema for the day and watching three horror films back to back. These include: Zack Cregger’s child abduction mystery Weapons, real-life couple Alison Brie and Dave Franco’s foray into co-dependency in Together and the Philippou brothers’ exploration of grief-induced obsession in Bring Her Back. You might be asking yourself why someone would do this, but the truth is that I’ve been in a cinema slump of sorts. By no means was it an intended slump, but once you miss one major release, you start missing out on others, and then it’s August and you’ve only seen three films since June. Of course, that’s a bit of an exaggeration, as I have seen my share of summer blockbusters (Superman & F4) and flops (I Know What You Did Last Summer), but regardless, what better way to kickstart my August, well, mid-August, than watching the three most recommended films of the summer so far?

It’s an understatement to say that Weapons might be one of the most talked-about movies this summer, let alone this year. Cregger’s sophomore follow-up to his debut film Barbarian (2022) ramps up his appetite for the absurd and unexplained. Even its use of voiceover narration aids in creating the allure of mystery, with an unknown young girl explaining the events leading up to the film. At 2:17 AM, she tells us, on a typically unremarkable Wednesday night, a class of third graders ran outside of their homes with their arms extended outwards, never to be seen again. It’s a fear plucked right out of a Stephen King novel or the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin. Why the children left and who took them remain a befuddling question that set the town ablaze, with only their teacher, Juliette (Julia Garner), left to blame. In Weapons, not only is the ‘why’ of the missing children far from straightforward, but so is the structure Cregger opts for. The film’s use of a nonlinear narrative jumps around from character to character, giving the audience an insight into what was missed earlier on, as well as an indication that perhaps all of what we’re witnessing might be unreliable to some extent.

Following its release, there has been a wide array of speculations towards what Weapons is actually about. The majority have argued for it being a clear allegory for American school shootings with its use of weapons as imagery(the gun Arthur sees in his nightmare), the memorial placed outside of the school, as well as the growing paranoia between the parents and school faculty on who to blame for their shared trauma. Other allegories, such as child trafficking, hidden abuse, and even social media brainwashing of young children, have been levied. I’d argue that the clear theme is grief and all the different ways it can take shape, although Cregger seems to enjoy the growing arguments around the allegory of it all. It should be noted that Cregger wrote the film in response to the tragic death of his friend Trever Moore, and it seeps into every shot of the film. Most of the choices made by the characters are centred around the fact that what they once knew as familiar to them has forever changed. Grief has the ability to take away your innocence (the missing children), impact your health (Gladys), and, in my case, the uncontrollable crying made me feel like my body was no longer my own (the weaponry of it all). Grief also brings up feelings of betrayal and confusion (the parents) and an inability to trust that anything will be normal again.

Although I admire and do relate in many ways to his depiction of grief and all of its reverberations, I wish I had enjoyed the big swings Cregger takes with the film; the choice to centre it on six different characters with widely different takes on the story should’ve left me wanting, but if anything, I became rather bored. Mystery wasn’t enough to sustain what felt like poor pacing, confusing character choices, deflated tension, and a relatively shallow attempt at convincing us that aging women’s bodies are the most horrifying thing around, which seems to be a theme within his work so far. Weapons might just be my marmite. Either you love it or you don’t—and I don’t.

If Weapons was the most talked about film, I’d say that Together would be slated as the most contentious of the three. This isn’t due to anything within the film itself, but instead allegations of plagiarism where Shanks, Brie, Franco and Neon were named in a suit filed this past May by a director who asserts his film was ripped off. It’ll take some time to figure out the truth behind what happened with the film and its pre-production, but for the sake of my diary entry, let’s pretend that there’s no copyright infringement at play here.

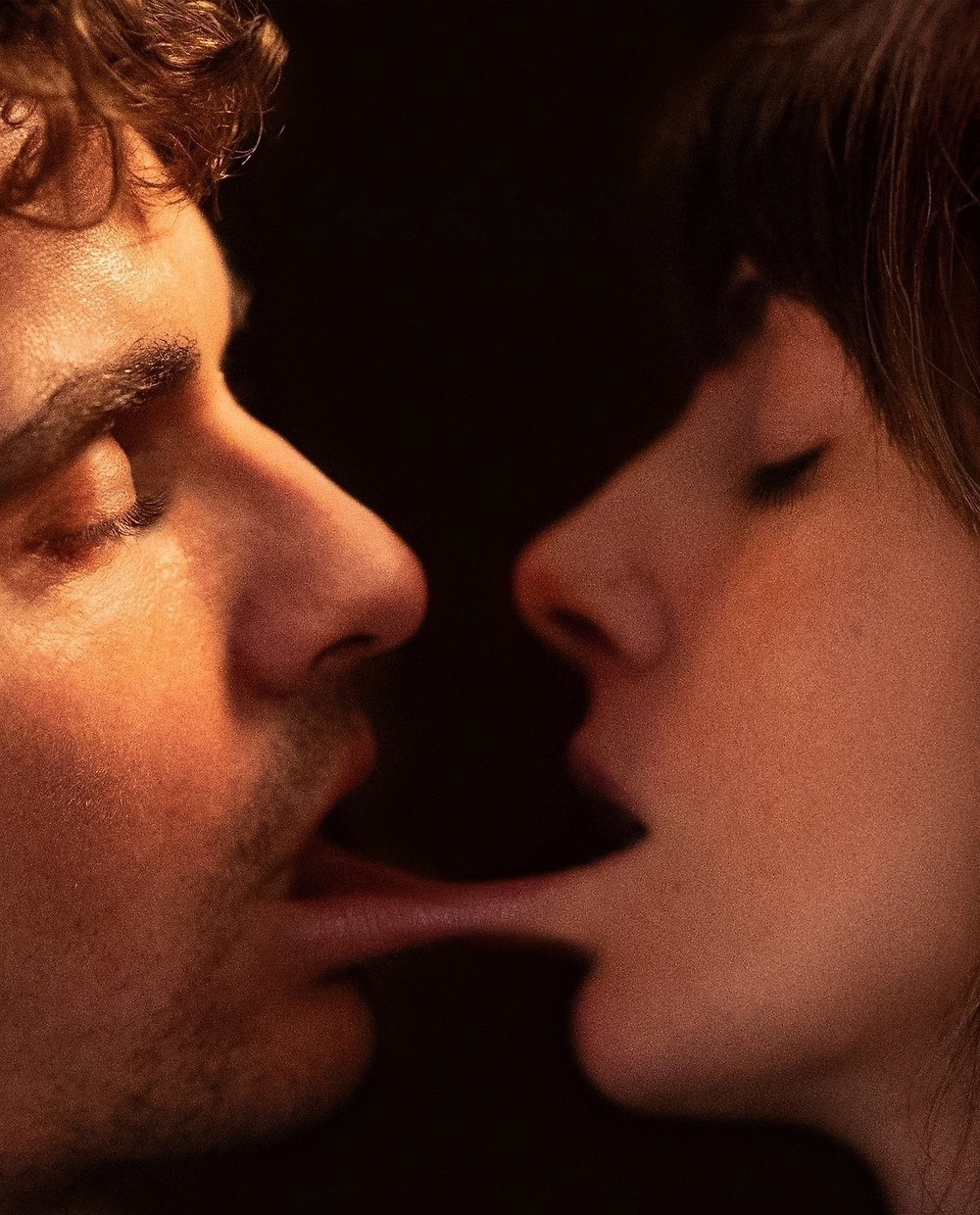

Together is a film made for a generation of emotionally avoidant adults. Through my extensive research, aka conversations with twenty and thirty-something-year-olds (friends, strangers in smoking areas, colleagues and more), everyone seems to want love, but are just not willing to put themselves out there, and, even when in relationships, aren’t willing to be honest about how truly they feel. We first meet our lead characters, Millie (Alison Brie) and her boyfriend, Tim (Dave Franco), at their going-away party. In separate conversations with friends, the pair lament and fondly reminisce about their relationship, a mirror to the growing push and pull between the contradicting forces within the film (city vs countryside, relationship vs singledom, freedom vs confinement). Tim wants to stay in the city, save his defunct music career and lead a life he remembers feeling good about. Millie, on the other hand, wants to move forward with a new job in a rural community school, a countryside house, and a future with Tim. This becomes startlingly clear when Millie proposes to Tim in front of all their friends, and his only response is something to the effect of “Are you joking?”, prompting an embarrassed reaction from Millie. The lack of honesty (Tim) and digging into their relationship (Millie) mould together a co-dependent monster waiting in the wings of this new idyllic chapter in their lives. Co-dependency, enmeshment, and conjoinment aren’t just elements of buzzing pop psychology but a fundamental aspect of the monstrosity that lies within Together. After a fateful accident that leads Tim to ingest some not-so-sterile water, he begins to feel a magnetic push towards Millie both emotionally and physically. In one incident, she leaves the house, and his body spins around, whipping him against the glass and tiles of his shower to the point he begins bleeding.

Throughout the film, the curse of enmeshment leads the couple to moments of gross levels of intimacy, whether that be Tim choking on Millie’s hair, their genitals getting stuck together or their hands (and bones) intertwining into each other, which Millie has to saw through with a rusty garden tool. Together brings ‘I want to live within your skin’ to new heights and, with it, poses a rather interesting inquiry into where total avoidance of pain and change will take you. The couple’s performance is the most satisfying part of the film; it makes every choice, good or bad, more understandable, and it helps that Brie and Franco have been married for over a decade. Drawing on their real-life experience and perhaps the bittersweet understandings of a long-term relationship, Franco and Brie portray the complexities with incredible compassion and gusto. It’s also a fascinating look into how the refusal to be honest about a relationship not working leads to a more sinister path than the breakup itself. To paraphrase Millie, “It’ll just get harder if we don’t split now.”

Frankly, at this point in the night, I was getting tired. One film had tested my patience, and the other had tested my current avoidance of questioning my own dating life. All I knew when I walked into Bring Her Back was that my best friend warned me against watching it for fears I might get triggered due to the nature of the film, and that it was directed by the Philippou brothers’, who made Talk To Me (2023), which remains one of my favourite horror releases of the 2020s so far. Triggered wouldn’t be the word I’d use for my reaction to Bring Her Back, which, spoiler alert, was by far my favourite film of the three and also a film I will most likely not be rewatching for a long time. There are only so many words in the english language that could describe the utter confusion, shock, disgust and heartache the film left me, but what I found myself repeating over and over again as I left the cinema was (and apologies for my language here) ‘what the fuck?’ Bring Her Back places its audience right into a camcorder recording of what appears to be an occult ritual with unknown ramifications. The footage is dark, grizzly and oh-so-bloody, with no time wasted on building backstory for why the cult exists or where the practice comes from. What’s most important here is that there is nothing normal about what we’re about to see.

After the sudden death of their father, step-siblings Piper (Sora Wong) and Andy (Billy Barratt) are sent away to live with a foster mother for three months until Andy is old enough to apply for guardianship over his younger sister. Upon meeting their foster mother, Laura (Sally Hawkins) and her non-verbal foster child, Olivier (Jonah Wren Phillips), she explains that she lost her child, Cathy, a few years ago and that she was also visually impaired, similar to Piper. Throughout their stay, Laura takes a fancy to Piper, allowing her to sleep in her deceased daughter’s room, showering her with affection whilst being cruel and outwardly manipulative towards Andy, who doesn’t buy into her performance for good reason. It is revealed that Laura has possession of the tapes we were first introduced to at the start of the film and is using the occult ritual to bring her daughter back by placing the spirit of her daughter within Oliver. As the film continues, we discover her plan of an eventual transfer of Cathy’s spirit into the body of Piper, but with the stipulation that Laura kills her the same way her daughter died—by drowning her.

I would go into just how utterly insane Laura is as a character—she even goes as far as throwing her piss over Andy at night so he believes he’s wetting the bed, poisoning his creatine, and gaslighting Piper into believing that he hit her—but we’d be here all day and I need to leave some surprises for you to experience firsthand. What I will say is that Hawkin’s engrossing portrayal of a woman, in deep mourning to the point of utter disrepair and disregard for the lives of those around her, is nothing short of monumental. If not for the decades-long industry slight against horror (hopefully nullified by The Substance and its award campaign), I would say she’s a shoo-in for Best Actress. There’s something so raw and yet utterly constructed about Laura; it’s as if throughout the film we catch glimpses of her former self before the onset of grief, but it’s promptly sheathed by her growing paranoia and obsession with the ritual. She pretends to everyone, but most importantly, to herself, that what she’s experienced with the death of her daughter is not only temporary but entirely reversible. To Laura, the lives of Oliver, Piper and Andy are nothing but a means to an end of getting her daughter back, perpetuating the same cycle of hurt and abuse she claims to be saving her daughter from. Bring Her Back is a harrowing portrayal of a woman who will stop at nothing to get back to a life she can never return to. It sits at the bottom of your stomach like a rock, full and uncomfortable, forcing you to reckon with the grotesque nature of what grief can do to someone.

It might be apparent now, but there exists an unmistakable connection between all three films beyond just genre—that being loss. The loss of youth, health, and safety in the case of Weapons, loss of identity, partnership, and understanding for Together, and the obvious loss of a loved one and control in Bring Her Back. Perhaps watching them one after the other didn’t help with my sleep that night, but it allowed me to think of all three films as congruent with one another rather than as separate entities. All three films have clear and distinct identities, with creative forces that unquestionably understand the stories they are telling, regardless of whether that translates for me. They have also stayed with me in different ways, with my current grappling on why Weapons didn’t work for me, my current hyperfixation on whether or not heterofatalism inspired Together (I’d argue it needs to be analysed through this lens) and my endless appreciation for Bring Her Back and Sally Hawkins. The whiplash between the good, the bad and the not-my-favourite-but-kinda-enjoyable of it all, has reiterated the fact that there is nothing better than spending the day at the movies. This is very ‘movies rock’ of me to say, but cinema truly is one of the purest forms of human connection and expression. It is also with the greatest pleasure that I can confirm my slump has been put to rest. Maybe that’s what August is for, a month of reset, renewal and reconfiguring for September and all that it brings.