The film theorist revolutionised cinema with her theory of the ‘male gaze’ in 1975. As a new season of her film work takes place at the BFI, she looks back on the political context that led her to write Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, her interest in mythology and how technology has changed our spectatorial positions altogether.

When film theorist and filmmaker Laura Mulvey published her seminal essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” fifty years ago, it reshaped the landscape of film theory for generations to come. Her intervention not only transformed how women are represented on screen but also our relationship as spectators to what we see, what we desire and the machinations of the cinematic apparatus as one of ideological seduction. In recognition of her achievements, the BFI recently awarded Mulvey a BFI Fellowship, accompanied by a retrospective season at BFI Southbank, “Laura Mulvey: Thinking Through Film,” now available on BFI Player.

Mulvey, who is most well-known for coining the now-ubiquitous term ‘male gaze’, developed her expansive essay out of an early interest in psychoanalytic theories which provided her with a framework to critique the misogynistic construction of classical Hollywood cinema. These structures positioned the male spectator at the centre of cinematic pleasure while reducing on-screen women to objects of fetishistic display. Over the decades, Mulvey has written various books that explore melodrama, semiotics, and feminist film theory. She has also extended her initial insights in Visual Pleasure to consider fetishism and the representation of the female body, while additionally exploring how female curiosity in cinema can activate subversive, investigative modes of looking – allowing female characters to see differently, even waywardly, and to disrupt the visual regimes that seek to contain them.

Across her own filmography composed of eight films, Mulvey often took similar approaches to trouble the position of the spectator, through Brechtian forms of distantiation to expose the construction of cinematic illusion and spectacle, while also crafting narratives that centred women and their labour – both within the domestic and artistic spheres. Influenced both by Marx and Freud, Mulvey’s work is as concerned with labour and unions as it is with female self-representation and she consistently considers the intertwined nature of feminist and class struggles. However, such a concern in the material reality of women is also framed by a grander structure through Mulvey and Wollen’s interest in how history intersects with myth, as their works scrutinise and trouble the positions of women within the myth of the Amazonian women in Penthesilea: Queen of the Amazons (1974) and the enigma of femininity embodied by the sphinx in Riddles of the Sphinx (1977). Working in the tradition of the avant-garde, inspired by figures including Hollis Frampton and Jean-Luc Godard, Mulvey’s films co-directed with Peter Wollen fit both into the realm of the essay film and also into untraditional forms of portraiture of female pioneers including Amy Johnson, the first female pilot to fly solo from London to Australia, or Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.

In this interview, Mulvey speaks to A Rabbit’s Foot about how the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1970s reshaped her relationship to cinema, her longstanding collaboration with Wollen, and how spectatorship has evolved in the fifty years since the emergence of the ‘male gaze’.

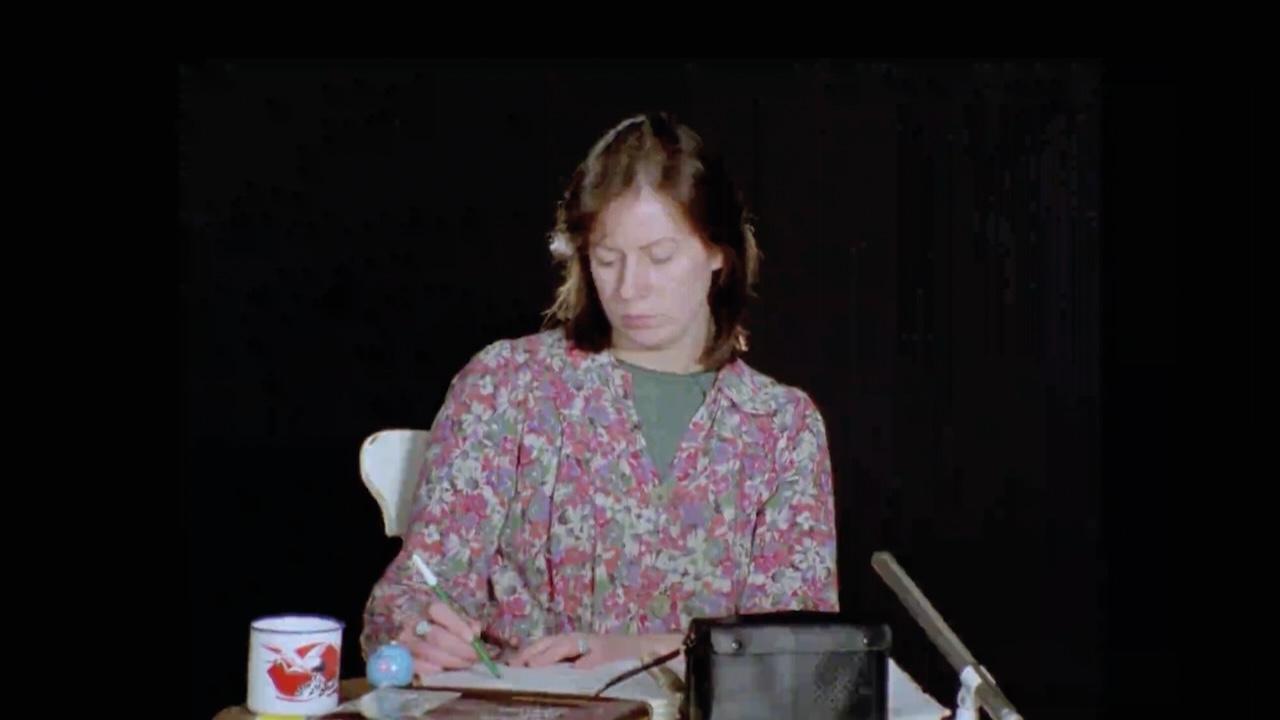

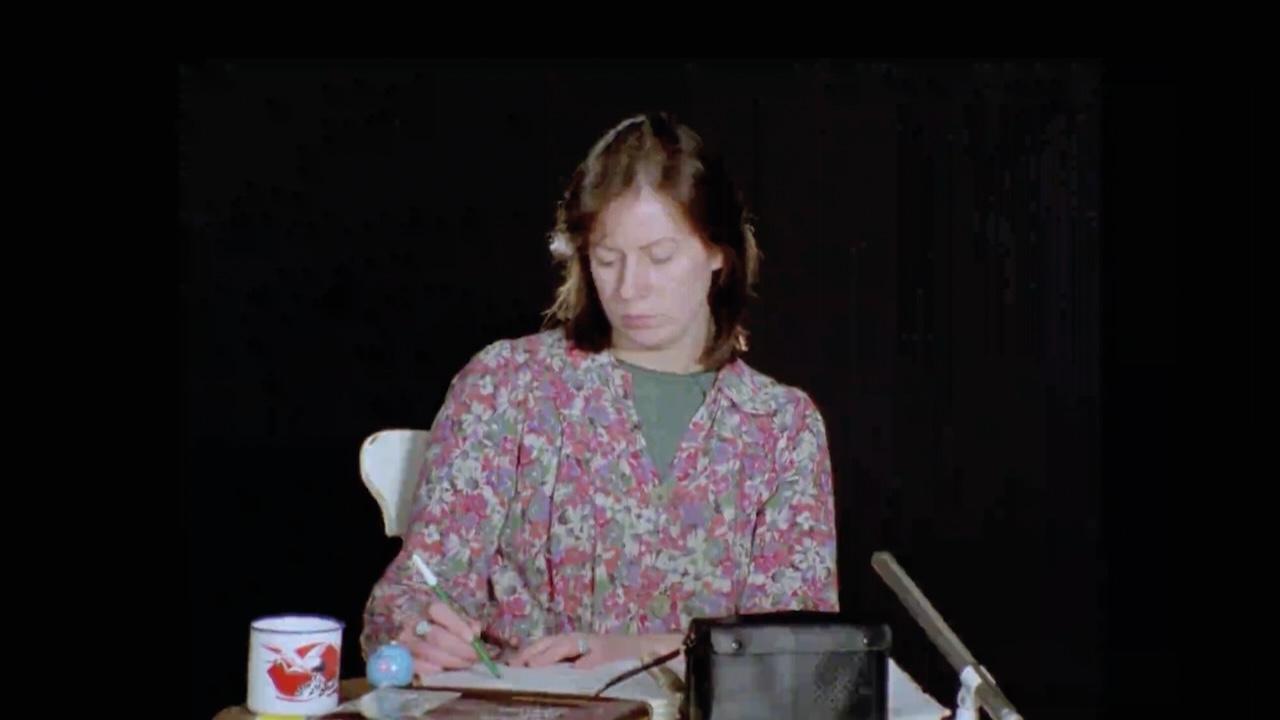

Riddles of the Sphinx (1977), directed by Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen

Cici Peng: What made you interested in avant-garde cinema?

Laura Mulvey: Well, first of all, the influence and impact of the women’s Liberation Movement turned my interest very much away from the Hollywood cinema that I’d loved so much. I started watching them with a sense of irritation, I couldn’t abandon myself into the screen or story in the same way. I was part of a group that has been discussed quite a lot–the Feminist Studies Group. That was where we started to read Freud, who offered a new vernacular to speaking and thinking about gender and sexuality and changed my spectatorial position.

I knew that women had been exploited by cinema over the years and had been marginalized within its production. So I had no interest in its traditional conventions. One would need to break the rules, rewrite the rules and invent a new kind of cinema. But one doesn’t necessarily invent a new kind of cinema out of the blue. So, what I called an objective alliance with “cinemas that had broken the rules” had actually become pointers to the way in which such a tradition could be challenged and present a new path forward.

In another way, Hollywood cinema was also coming to an end. Its time was over. Other things were happening. New kinds of films were arriving. I mean, Godard’s Vent D’est (1970) inspired Peter [Wollen’s] seminal essay on counter-cinema, which then informed our first film Penthesilea: Queen of the Amazons together. For my retrospective, I programmed other extraordinary, avant-garde films to put our work in context. Zorns Lemma (1970) by Hollis Frampton was really important to us. If you can imagine seeing that for the first time in 1971, you would have never seen anything like it.

CP: Many of your films are interested in women’s myth as it intersects with history. Can you talk a bit about the positioning of myth in your films?

LM: The first rather obvious answer before getting onto the question of myth is that all Peter’s and my films were based on a pre-existing text. Even Crystal Gazing (1982) was based on the adaptation of the novel Fabian published in Germany in 1931 by Erich Kästner. But the ones that were built on myths are also interested in not just us retelling a story, but in myth as a cultural object that has retold these stories many, many times. And it seemed to us that those stories that had been retold were ones that had a special place in culture and, in a sense, cultures would return to them perhaps at different moments in history to reimagine them. Now, in the case of Penthesilea: Queen of the Amazons, what attracted us to a myth of the Amazons was the number of re-interpretations. In Homer’s Iliad, there’s a short reference to the Amazons going to Troy and the encounter between Achilles and Penthesilea. Achilles kills Penthesilea and falls in love with her as she dies. Then, we were interested in the way that Heinrich von Kleist in the early 19th century had picked up this story and reversed the roles. So Penthesilea kills Achilles and falls in love with him as he dies. So this seemed to us to be a really interesting gender transition in which the meaning of the male killing the female and the female killing the male wasn’t the same. There was suddenly, with the Kleist version, a kind of perversity to it. The man killing the heroine, falling in love, seemed tragic but normal, if you see what I mean. The heroine killing the hero seemed perverse. So we were interested in the way in which meaning can shift when gender shifts.

Riddles of the Sphinx (1977), directed by Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen

CP: Can you talk about how you were thinking of dispelling cinematic conventions on the level of form?

LM: Penthesilea is a film without editing, and we were interested in the extended shots that made people physically aware of how unusual it is to see a film without edits. Of course, a film without editing involves a very different kind of subjectivity. It involves this extended duration of time in which the passing of time becomes palpable.

CP: With Riddles of the Sphinx, this was a similar logic with your panning shots which continue for a whole rotation?

LM: With the 360 degree movement of the pan, it makes it hard to linger specifically on a character and we intentionally avoided showing Louise’s face, thus troubling the spectator’s desire for identification with the on-screen protagonist. When we first came up with the idea of the 360 degree pan, we were thinking very much in terms of a circle and its relationship to domestic space and how it’s something womb-like metaphorically. What we had hoped for, is that the movement of the camera is detached from identification, and becomes the movement of the apparatus. So the spectator’s consciousness of the apparatus is very much inscribed into the strategy of the film.

The Other Side of the Underneath (1982), directed by Jane Arden

CP: In Riddles of the Sphinx, why did you want to focus on motherhood specifically and challenge that representation?

LM: There’s an element of critiquing the tradition of the strongest iconographical images of Christianity, of total European culture, with the bodily juxtaposition of mother and child. The mother is always depicted holding the child, as one can see in the opening pan of Riddles of the Sphinx. And so, in a sense, what we were interested in was to open up that physical dyad. We wanted to question the labour of childcare falling on the mother, but also to psychoanalytically explore the Oedipus narrative in which the child’s trajectory into the world and into society emphasis the mother as being the first primary physical relationship for the child, while culture is introduced through the child’s relationship to the father and society. So we were questioning that binary. And it was that Oedipal trajectory that we were emphasising by returning to the Sphinx, the riddle, the hieroglyph, the enigma, and so on. Not resolving it, as it were, but trying to turn that dynamic into a question.

CP: You mentioned at your BFI Symposium that Riddles of the Sphinx follows from the logic of the melodrama in which female characters’ emotional lives are often externalised onto their surrounding spaces and the mise-en-scene. Can you elaborate on that?

LM: For instance, at the beginning of the film, the colour scheme is designed around blue and yellow and green. And we only introduced red, very much at the end, when Louise is wearing a red dress. As red is introduced, there’s a change in the mother-child relationship too, as she is no longer carrying her child, thus a level of separation has occurred. And, of course, for melodrama, music was always very significant. The music in those early sequences of Riddles gives it an implicit beat without a beat, which echoes the movement of the camera while also being expressive of emotion. If I can just add one thing, that sense of mise-en-scene was also important in the first two performed sequences of Amy! (1979) because in that work, the meaning of Amy’s shift from her identification as feminine to her identification as more masculine, due to her profession [as a pilot], is all done through the shifts in the mise-en-scene and the lighting. So in a sense, I think Amy! has that melodramatic tradition written into it as well.

The Bad Sister (1983), directed by Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen

CP: Your film The Bad Sister (1983) is the opposite of Riddles of the Sphinx, where we’re seeing the perspective of the daughter instead of that of the mother. But The Bad Sister uses a more conventional fictional structure and was made with Channel 4. Can you talk about that choice?

LM: Throughout Peter’s and my films, if you look at them as an arc, we were responding to different circumstances. Penthesilea was made on a shoestring as a transitional moment for cinema into the avant-garde movement. And in a way, The Bad Sister was made with a very large budget and a full crew. Again, it was a transitional moment around Channel 4 and Film on 4 that grew out of the avant-garde movement. Our films were made in response to situations and to opportunities. So when the horizons shifted, we shifted too.

The Bad Sister was a much more difficult enterprise. And because of the conditions we were working under, we had to have a proper script. Peter and I were also used to working with actors who were able to improvise and who were able to respond to situations. I’m not saying that our cast in The Bad Sister couldn’t have done that, but the conditions of work didn’t really allow for spontaneity. Both Peter and I found that more conventional labour of directing quite difficult to take on.

There is no gender stability in spectatorship.

Laura Mulvey

CP: How did you think about the role of your central protagonist? She is quite active and perhaps follows the line of your essay “Pandora’s Box: Topographies of Curiosity”. I love this line from the essay: “An active, investigative look, but one that was also associated with the feminine, suggested a way out of the rather too neat binary opposition between the spectator’s gaze, constructed as active and voyeuristic, implicitly coded as masculine, and the female image on the screen, passive and exhibitionist.”

LM: That’s completely true. Jane, the protagonist, has an active gaze, she looks both at her partner’s other lover, and she engages in a form of investigation. Jane reinvents herself as an image when she comes back from the party, she cuts her hair and becomes more androgynous. There’s a certain kind of similarity there to Amy!, producing a change within gender roles and identification.

CP: Now 50 years on from the visual pleasure essay, do you think our spectatorial positions have changed or cinema has changed its positionality with how we look?

Well, I think it has had to change. It hasn’t had much choice. Technology has changed so much that people now consume cinema on so many different platforms and so many different modes which has ultimately transformed spectatorship. But for me, what interested me particularly when I was writing my book, Death 24x a Second (2006), was the way in which the spectator could become an active spectator and intervene in the flow of the film and discover completely new, unexpected kinds of spectatorships by stopping the film, reversing the film, repeating sequences and so on. And that seemed to render my visual pleasure argument technologically archaic, but also suggest that there is no gender stability in spectatorship. The new spectator, either pensive or possessive, could reinvent themselves in relation to identification as they thought, to fit their desire, as it were.

Laura Mulvey: Thinking Through Film film collection is currently available on BFI Player. Laura’s curated selection of Big Screen Classics, running throughout December at BFI Southbank: Laura Mulvey Selects