The French fine jewellery house has always shared an intimate relationship with cinema, with Cartier’s craftsmanship and artistic creativity brought to life through the sirens of the screen. From Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard and Alain Delon’s penchant for the Tank watch to actress María Félix’s iconic snake necklace and the rosary in Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme, we dive into Cartier’s most memorable movie moments.

One of the first watches I coveted was a Cartier Tank Américaine.

It was not spied on a billboard at Heathrow, or on the wrist of an effete model, but instead in a republished photograph in a movie magazine (I believe the editorial was smartly titled Americaine Boy). It showed the great Alain Delon, and Jean Pierre-Melville, the director of Le Samouraï (1967), proudly flashing their Tank watches like mischievous school kids who’d returned with treasure.

As a fan of Delon’s style—later an admirer of the tough guy Melville’s—I knew that whatever he wore off-screen was a sign of impeccable taste (there are legions of writers dedicated to deconstructing exactly this). And ever since, the Cartier Tank was synonymous with Delon; the poster boy of Gallic cool.

Over the years, Cartier has represented more than a jewellery maker. It is a co-star in itself; an accessory to moments on- and off-screen. And a relationship with cinema that has thrived for over a hundred years.

In 1926, the great actor—and original Latin Lover—Rudolph Valentino became so enamoured with his Tank watch that he refused to remove it when filming the 1926 film The Son of the Sheik (there’s a hilarious send-up to this in the first five minutes of 1968’s The Party with Peter Sellers). It was the first of a long heritage of actors wearing their personal Cartier pieces while filming.

The inimitable Gloria Swanson would also insist on wearing her dazzling rock crystal, diamond, and platinum bracelets in Cyril Gardner’s Perfect Understanding (1933). They returned again in Billy Wilder’s timeless thriller Sunset Boulevard (1950), on the wrist of Swanson’s troubled Norma Desmond. Yet what they also added was narrative to her character; a woman who came from the “Golden Age” of stardom. When taste was power.

Audrey Hepburn was another devotee to the maison. The British icon wore Cartier in the 1966 heist caper How to Steal a Million. Marlene Dietrich would wear her Cartier earrings—gifted by the original French tough guy Jean Gabin— everywhere. We’ve heard of actors going off-script with their dialogue. Here were examples of them going off-wardrobe. The first time the maison’s jewellery was used as an official prop was in Jean Cocteau’s majestic, dreamlike classic La Belle et La Bête (1946). These were loaned by Cartier.

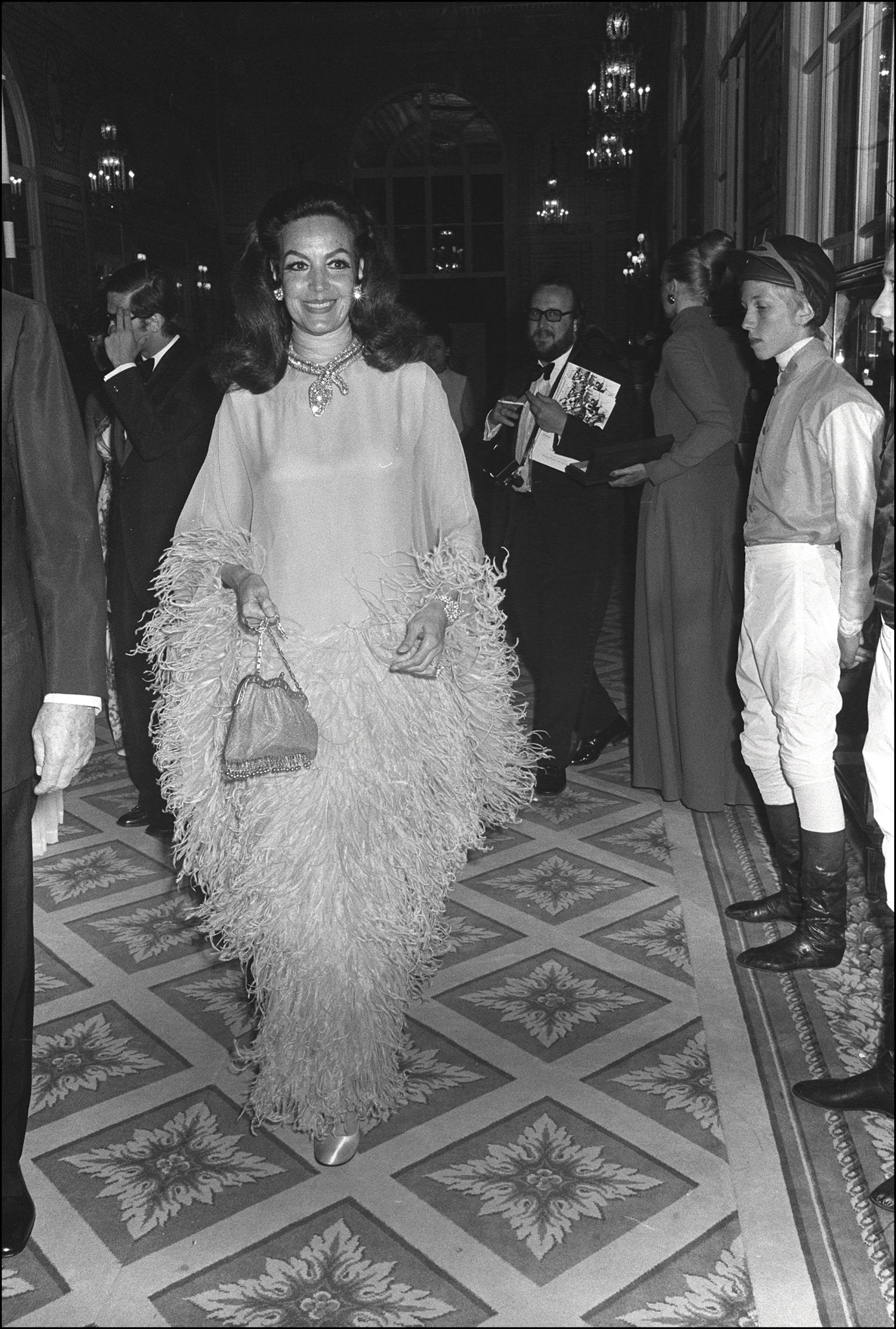

But perhaps one of the most telling examples returns, again, to Delon—or rather, his former fiancée, the inimitable Romy Schneider, who was equally devoted to her Baignoire watch. You can see it in La Piscine (1969). There was also María Félix, the Mexican actress nicknamed La Doña, who was never seen outside her house without her Cartier jewellery—a woman with impeccable style and charisma. Her favoured companion was the spiral snake necklace.

Cinema is the great mirror of the zeitgeist. It was obvious that Cartier’s jewellery and watches would have starring roles in some of film’s great works. But few would’ve known that it would flourish a hundred years after Valentino’s sheikh.

Where else would filmmakers find jewellery that dazzled so radiantly on screen?

Wide-eyed observers would have spotted the rosary necklace—set with rubies, emeralds and diamonds—in Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme (2025). Inspired by a cross pendant made by Cartier in the 1880s, this was a special-order from High Jewellery, the peak of Cartier’s bespoke craftsmanship (if it is good enough for the stars, it would be more than enough for production). You can see, on two occasions, the iconic red ring box also makes an appearance.

The maison doesn’t publicise it too much, but it has often been called on to loan pieces from its Cartier Collection archives—under High Jewellery. In Maria (2024), the Maria Callas biopic directed by Pablo Larrain, Angelina Jolie wore a rose clip Cartier brooch that belonged to the real Callas. There is also a stunning figurative panther brooch—not the original, but similar to another from Callas’s personal collection. The panther has been a Cartier emblem since 1914. Both were loaned by the collection for filming.

As someone who deeply admires Callas, knowing that Jolie was wearing La Divina’s jewellery brings texture to the film and to her portrayal of the character. It is also very La Callas by nature—opulent to the very end.

The Cartier Collection isn’t simply an archive to the past, it is also a chronicler of the present. Anyone who remembers Timothée Chalamet’s excellent red-carpet work on the recent premieres of Dune: Part Two (2024) and Wonka (2023) will have seen his unique necklaces, set with over 800 precious stones. Each was commissioned to represent the atmosphere of Arrakis and Wonka’s magical worlds, and they are recent additions to the Cartier Collection’s 3,000 pieces, safely kept in Geneva, Switzerland.

Every year at the Venice Film Festival, we see Cartier’s elegant red on the partnership mastheads.

Aside from being a patron to the festival, since 2021, the maison has awarded the Cartier Glory to the Filmmaker Award to a personality who has made, in Cartier’s words, “an original

contribution to the contemporary film industry”. It’s a prestigious, if short, list: Ridley Scott, Walter Hill, and Anderson have all been honoured.

The award is a genuine and subtle commitment to the arts—a look forward, instead of remaining firmly committed to preserving the past.

It is characterised by the panther, the maison’s elegant animal symbol.

It was obvious, then, that Anderson would commission the artisans at Cartier for The Phoenician Scheme. But look carefully, and the maison continues to collaborate with the very best artists in contemporary cinema. There was Sofia Coppola’s superb film for the Panthère de Cartier watch; as much a love letter to empowered wom- en as a highlight of this iconic timepiece. Italian director Luca Guadagnino produced a series of mini romances, all using Cartier’s engagement rings. In a short launch for the Grain de Café collection, filmmaker Alex Prager looked to Grace Kelly while styling Elle Fanning. The Princess of Monaco was famously devoted to Cartier.

Perhaps fewer collaborations are after my own heart than Guy Ritchie’s. In his campaign, a homage to the French New Wave—that era of singular French cool—he spotlights the Cartier Tank Française watch.

“I have to move forward with a certain amount of momentum,” Ritchie says of the film, which has Rami Malek crossing a bridge while witnessing Catherine Deneuve throughout the ages. “A sort of metaphorical bridge in time.”

It’s a summation of why Cartier has remained so vital to film and filmmakers a century on: its artistry exists on a bridge in time; one nod to history but always moving forward. There are few arts where this is more relevant than cinema.

María Félix photographed by Daniel Simon during the delivery of The Riding Crop of Gold in Deauville, 19th August 1973. She is wearing her snake necklace commissioned from Cartier Paris in 1968.

Foot Note

Nicknamed La Doña—or ’The Lady’—María Félix was a Mexican actress and one of Cartier’s most enduring muses. Born in 1914, Félix was heavily embedded in the art world, particularly the Surrealist movement. Félix worked, inspired, and engaged with artists and filmmakers such as André Breton, Luis Buñuel, Leonora Carrington, Jean Cocteau, Diego Rivera, Leonor Fini, Stanislao Lepri, and Remedios Varo. Her artistry extended to her personal style and in particular Félix’s extravagant taste in jewellery. In 1968, Cartier created a snake necklace for the actress, with 2,473 diamonds recreating the shimmer of the serpent’s skin. And in 1975 she went one step further, commissioning a necklace based on two crocodiles. The story goes that she brought a live baby crocodile into the Cartier workshop to model it on (the atelier had to work quickly, so the crocodiles didn’t get too big). Rendered in 1,023 yellow diamonds and 1,060 emeralds, the resulting feeling of the necklace is protection and fierceness alongside unapologetic opulence.

Foot Note

Nicknamed La Doña—or ’The Lady’—María Félix was a Mexican actress and one of Cartier’s most enduring muses. Born in 1914, Félix was heavily embedded in the art world, particularly the Surrealist movement. Félix worked, inspired, and engaged with artists and filmmakers such as André Breton, Luis Buñuel, Leonora Carrington, Jean Cocteau, Diego Rivera, Leonor Fini, Stanislao Lepri, and Remedios Varo. Her artistry extended to her personal style and in particular Félix’s extravagant taste in jewellery. In 1968, Cartier created a snake necklace for the actress, with 2,473 diamonds recreating the shimmer of the serpent’s skin. And in 1975 she went one step further, commissioning a necklace based on two crocodiles. The story goes that she brought a live baby crocodile into the Cartier workshop to model it on (the atelier had to work quickly, so the crocodiles didn’t get too big). Rendered in 1,023 yellow diamonds and 1,060 emeralds, the resulting feeling of the necklace is protection and fierceness alongside unapologetic opulence.