A Rabbit’s Foot spoke to Iranian director Sepideh Farsi about capturing the struggle and spirit of Gaza via a series of intimate video calls with Palestinian photojournalist Fatma Hassona, who was targeted and killed by Israeli forces before the film’s premiere in Cannes.

A few weeks ago at the Cannes Film Festival, around the same time as Óliver Laxe’s fest favourite Sirât held its premiere at the iconic Palais du Cinéma, Iranian filmmaker and activist Sepideh Farsi’s documentary Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk was receiving its own impassioned standing ovation at Cinéma Olympia, tucked away just off the Croisette.

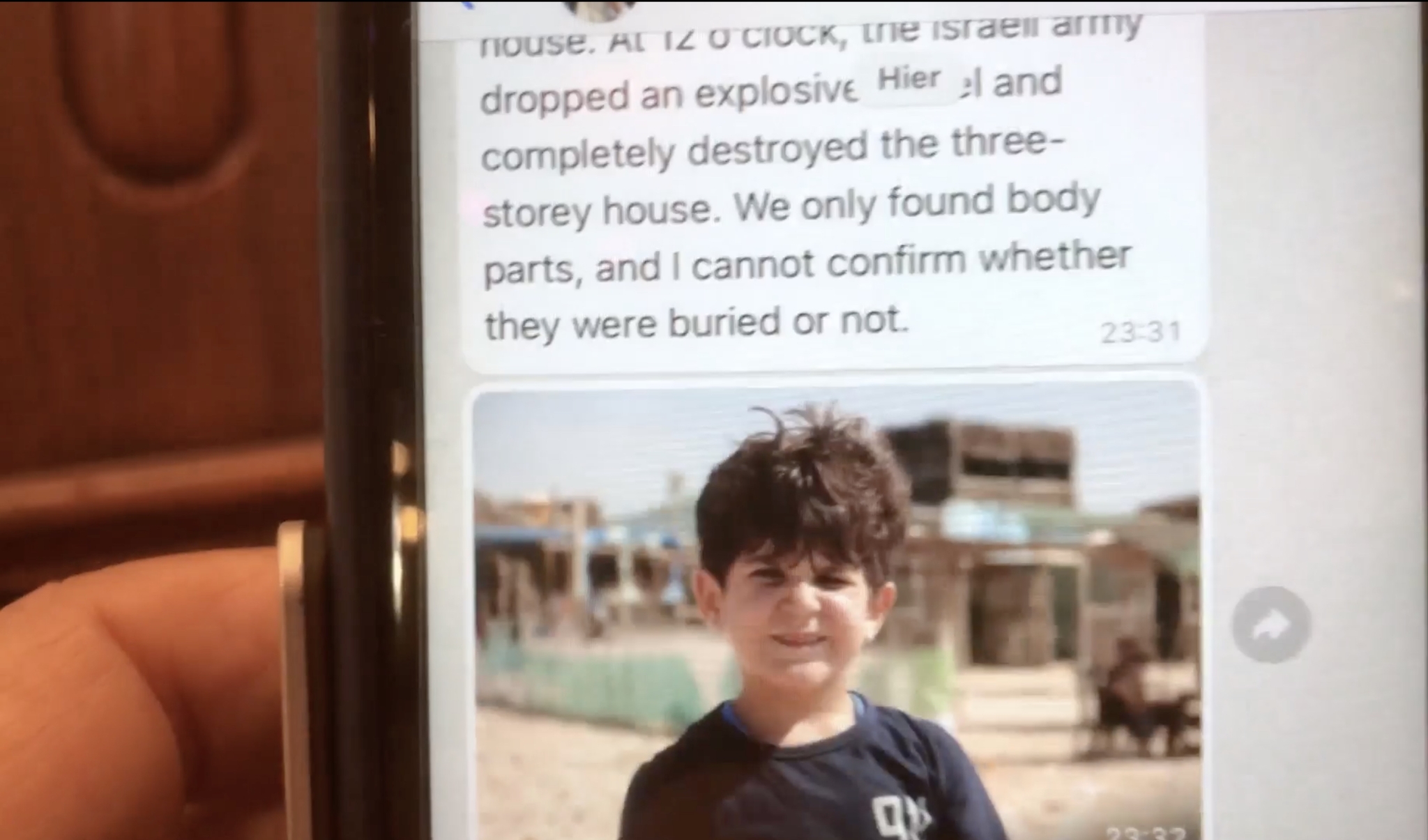

A crucially unsensational document of the genocide currently taking place in Gaza, Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk is told through the eyes of Palestinian photojournalist and poet Fatma Hassona, who, alongside her family, was targeted and killed in her Gaza home by Israeli forces only a day after Farsi informed her the film would be premiering at Cannes.

Presented via a series of video calls filmed over the past year between Farsi and Hassona—with Farsi recording their conversations over a glitchy internet connection—we watch Hassona reflect on the reality of the war as it happens in real time, accompanied by photographs of the city’s destruction taken by the 25 year-old herself.

“I asked [Fatma] what it meant to document the war in Gaza,” Sepideh says when I ask her about the meaning of the film’s title at a roundtable after the screening. “She said, taking photos in Gaza today is like putting your soul on your hands and walking the streets. It remained with me.” At the end of the film, the director took the stage to hold up a portrait of Hassona, jolting the audience, previously sitting in stunned silence, into rapturous applause. By this point, you are painfully familiar with the 25 year-old Gaza native: her unimpeachable smile; her awe-inspiring optimism; her art; her family and friends; her Gaza (as Hassona refers to the city in the film), standing resiliently against the most traumatic of realities.

We sat down with Farsi at Cannes to discuss her close relationship with Hassona, the genocide happening in Gaza, and the making of Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk, which intimately captures the struggle and spirit of the Palestinian people through the lens of one of Gaza’s brightest. As far as filmmaking goes, it doesn’t get more urgent than this.

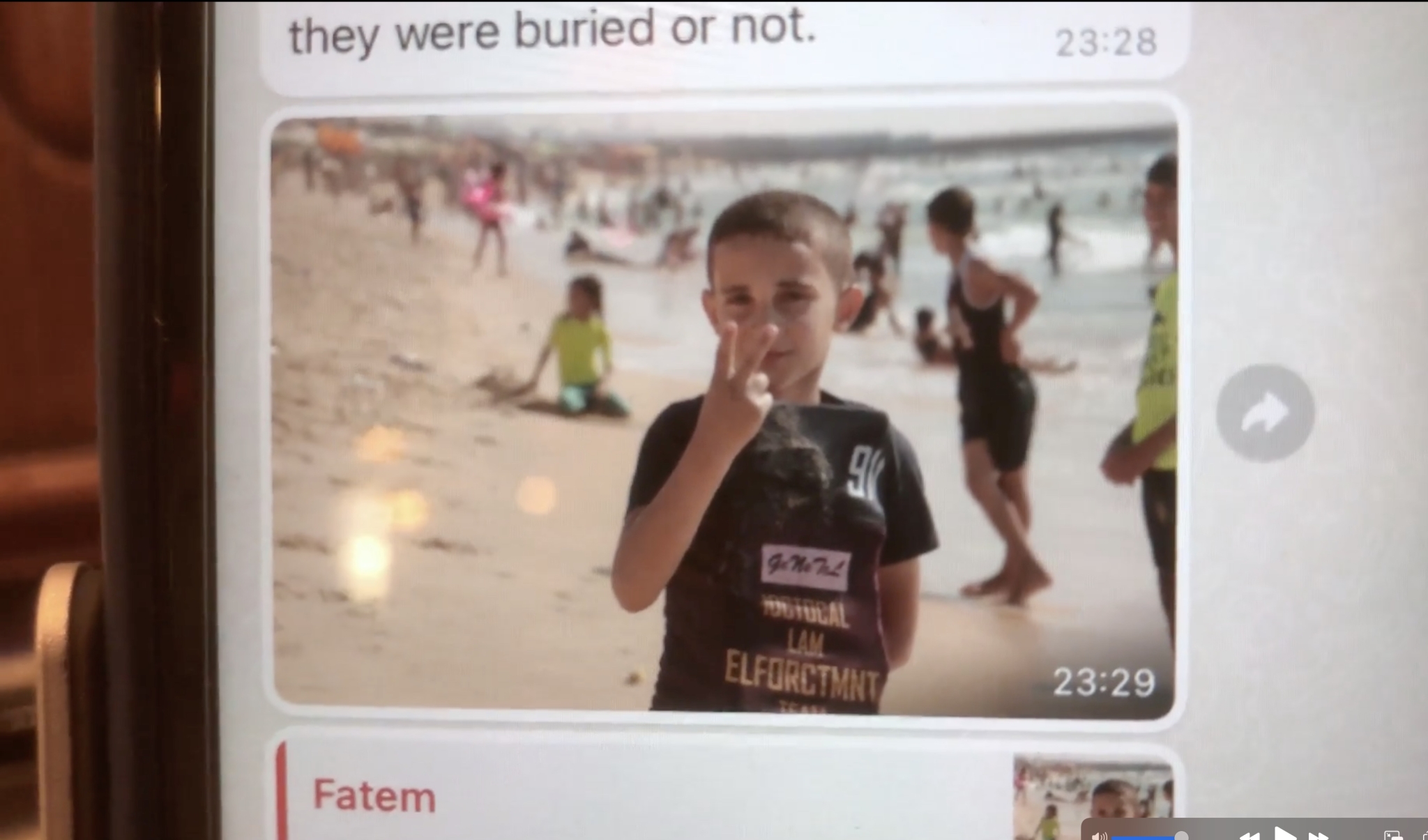

Fatma Hassona. Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk (dir. Sepideh Farsi, 2025).

I was struck by Fatma’s smile. It stays with you long after the movie ends.

I was surprised at the beginning. I was fascinated by it. I asked her about it. How could you talk about these bombings with such a smile? The reality of her situation was and still is so horrible. You need to keep a sense of humour, you need to keep a bit of distance, otherwise you collapse. I think it was her way of protecting herself. But it was also something natural. Sometimes her smile was mischievous. She had a spectrum of different smiles. Some were very bright, some were a bit greyish, and had other meanings to them. Sometimes they were ironic, and other times frivolous. But she was always very lively. Despite it all, it was a very joyful gathering every time we called each other.

How has the last month been for you?

I went to a TV session and they told me it’s been a month since she was killed. What? It’s already been a month? It was a shock to me. I hadn’t realised how many days had passed. I’m trying to cope. I’m luckily very busy. It’s strange, because I see things differently now. This time last year I was at Cannes, secretly filming our conversation at the Majestic. And now she’s gone. Her photos are exhibited at the Majestic, and she’s not here to see it.

What emotions were running through your head when you heard the news?

Disbelief. I am angry, absolutely. But I still can’t believe that it has happened. To me, she’s alive. I know she’s gone, but when I watch the film, she’s there.

Her liveliness is something that was amazing, but not only that, the children we see in the movie—her brothers. They were very optimistic, much more than we are here. When the ceasefire happened, I was very skeptical, but I never told her. I said to myself, “you do not have the right to show your skepticism, because if they believe in it, we have to follow them. I tried to wipe those doubts from my mind and be as happy as I could while I was talking to her. In other moments, I was more personal. When we spoke about God and other aspects of life I would tell her what I thought. But when it came to this subject, I would hold back.

I also think religion is one thing that’s helped them during this constant horror. Their belief in a God, who to me seemed like a very cruel one but to her seemed like a merciful God. She kept saying that everything has a purpose on Earth. That belief helped her.

I overheard someone saying that they didn’t believe that you had spoken to her the day before she was killed. How can we make those people understand the daily reality of people living in Gaza?

The human mind has a way of shutting down the things that are too harsh. But it’s also very cordish. I have very good friends who I love who tell me that they can’t watch videos coming out from Gaza. They can’t sleep otherwise, they say. I said, by the fact of you not watching them do you think they go away? Of course not. I understand and respect that some people are more sensitive and cannot take the graphic quality of those images. I force myself to watch them, because we owe it to them to see their faces, to listen to them. Many people choose to look away, or to deny. To ask how it’s possible? Well, it happened. I told her about the movie premiering at Cannes and she was gone the day after. It’s as simple as that. Ask the Israeli army. I don’t know about the timing, but it was targeted. I will send you the forensic protection for it. This has been confirmed by specialists. To me, it seems very clear. She’s not the first one, either. There was another journalist who was killed two days ago. They’re strong, they have military superiority. We have to admit it. As a historical fact, they eliminated [Ismail] Haniyeh when he was in Tehran. So, I mean, that shows how strong they are.

And they’re also able to operate seemingly with impunity.

Yes, this is the thing. It’s one thing to target your political opponents. It’s still not okay, but if it’s between Hamas and Netanyahu and the Islamic Republic of Iran, who are all dictators—I don’t think it’s a democracy anymore in Israel. It looks like one. They vote, but it doesn’t function—but I draw a clear line between targeting journalists, photographers, writers like Refaat Alareer, the Palestinian poet. He wrote poetry, and they targeted his sister’s house. He was killed with all his family there. And he knew it before it happened. He had written a poem a month earlier called ‘Some Strings’. It read, ‘if I die I’d like to take a piece of white cloth and make a kite that will fly in the skies.’ For God’s sake, hitting someone for poetry.

The title of the movie is a direct quote from Fatma. What initially struck you about that line that resonated so deeply?

She had a way of phrasing things. Very simple things. She would say, ‘I can’t leave Gaza, my Gaza needs me.’ Or ‘this is my everything.’ It’s wrong in English, but it’s so beautiful. I asked her what it meant to document the war in Gaza. She said, taking photos in Gaza today is like putting your soul on your hands and walking the streets. I asked her again a few months later, and she said, ah, did I say that? [Laughs] it had remained with me.

Juliette Binoche was put under fire at the opening ceremony for not signing the petition for a ceasefire. What do you make of the responsibility of those with platforms like her?

We all have a responsibility in this thing. Artists, filmmakers, well-known people, celebrities, jury presidents, festival directors have more, perhaps. Politicians have *much* more. Journalists also do have a big responsibility. All of you, you know, and me, as a filmmaker, of course. But as world citizens we have a responsibility. We have to walk the streets not buying certain products, and buy more actively other products. They are killing civilians, innocent people, starving them. The little girl in the film, she’s only five, and I received a photo from her Aunt last night…she’s so thin. And this is a family who have money. But money can’t buy it. When there’s no food, there’s no food. Why do we let this happen? The problem is that the politicians and governments have put us in a position of helplessness, and I think we really need to be more courageous and more and more vocal as citizens.

Some people with influence or platforms are afraid of being labelled as anti-semitic.

Yeah, ok, they will accuse me. I will say I’m not. So what? They tell me I’m a rabbit, I’ll say no I’m not. The European conscience is still feeling guilty about what happened in the Second World War, and no one is courageous enough to say that. Instead they displace the problem to Israel and Palestine, and anyone who is talking about this humanitarian crisis is accused of anti-semitism. When you say don’t kill children, they say you’re anti-semitic. Okay, fine. Where does it fit? If you are clear with your conscience, you can comfortably reject that categorisation. I’m anti-zionist, but I’m not anti-semitic. It’s a clear line.

When did you decide to shoot the phone screen instead of screen record?

I wanted to keep a low-resolution feel. Not sharp, not defined, quite dirty and pixelated. It communicated the frustration of the weak connection speed of our video calls. Sometimes my screen was dirty, and I would leave it dirty. It adds texture to the image. I kept the reflection of my hand and face in the image deliberately to bring myself in, but also to create another layer and take away from the flatness of the video. What I see in the random advertisement panels around the city [Cannes] is 100 times better quality than what I did, but it’s not cinema. It’s something else.

How much of the world turning a blind eye to what’s happening in Gaza is associated with Islamophobia in your opinion?

It’s linked. I’ve had this discussion many times with dear friends who do not admit exactly why they’re lacking so much empathy for the Palestinian women, for example. Because they have a lot of empathy for the Iranian women who are fighting against the veil, which I’m thankful for. But when it comes to Palestinian women, they keep quiet. I ask them what changed? They say, ‘well…did they condemn Hamas?’ What does Hamas have to do with this? If a woman is killed then a woman is killed. Just because she was wearing a veil because she’s Muslim it doesn’t make her death less horrible. I’ve lost friendships over that point.

Fatma mentions in the movie that Israel not only wants to erase the Palestinian people but erase their culture alongside it.

There are acts that prove that. Two days ago Israel attacked and shut down the land registry in the West Bank. Now you can’t prove that you own your own land. It allows the settlers to freely go about annexing villages. When they burn libraries, when they destroy cultural centres and mosques, or uproot old olive trees, it’s history being erased. They have the physical occupation of land and they also have the cultural occupation. To me, the fact that Palestinians are obliged to use Shekel as their money is a very intentional and absurd thing.

How did you notice that Fatma’s art changed during the period of time you had building this relationship with her?

Her art became more testimonial towards the end. Less romantic in her way of writing poetry. Her photography had certainly lost colour. But that’s also due to the sheer fact that the objects themselves had grown grey and black because of the destruction. But it’s true, when you put them next to each other, you see a clear change. I think she went from a romantic, picturesque style of photography to something harsher, something uncompromising. Her gaze was ripening, it was becoming more developed.

Did you make any changes to the film following Fatma’s death?

No. I didn’t want to.

What did it mean to you to have Fatma as a direct perspective into what is happening in Gaza right now? We’ve all been following along with the news, but you had such an intimate view into this war.

It was a miracle. I really believe it was accidental and beautiful. I could have met somebody else who might not have been so open. Who might not have had that brilliant smile. Who might not accept to collaborate. There was this thing that went beyond the film. We became like sisters. That’s also why it’s so hard for me now. She stopped being just the protagonist of my film. She became a part of my life. We never met physically, but we were very close.

You can show your support to the young people of Gaza by visiting the following links and donating. Find them here and here.