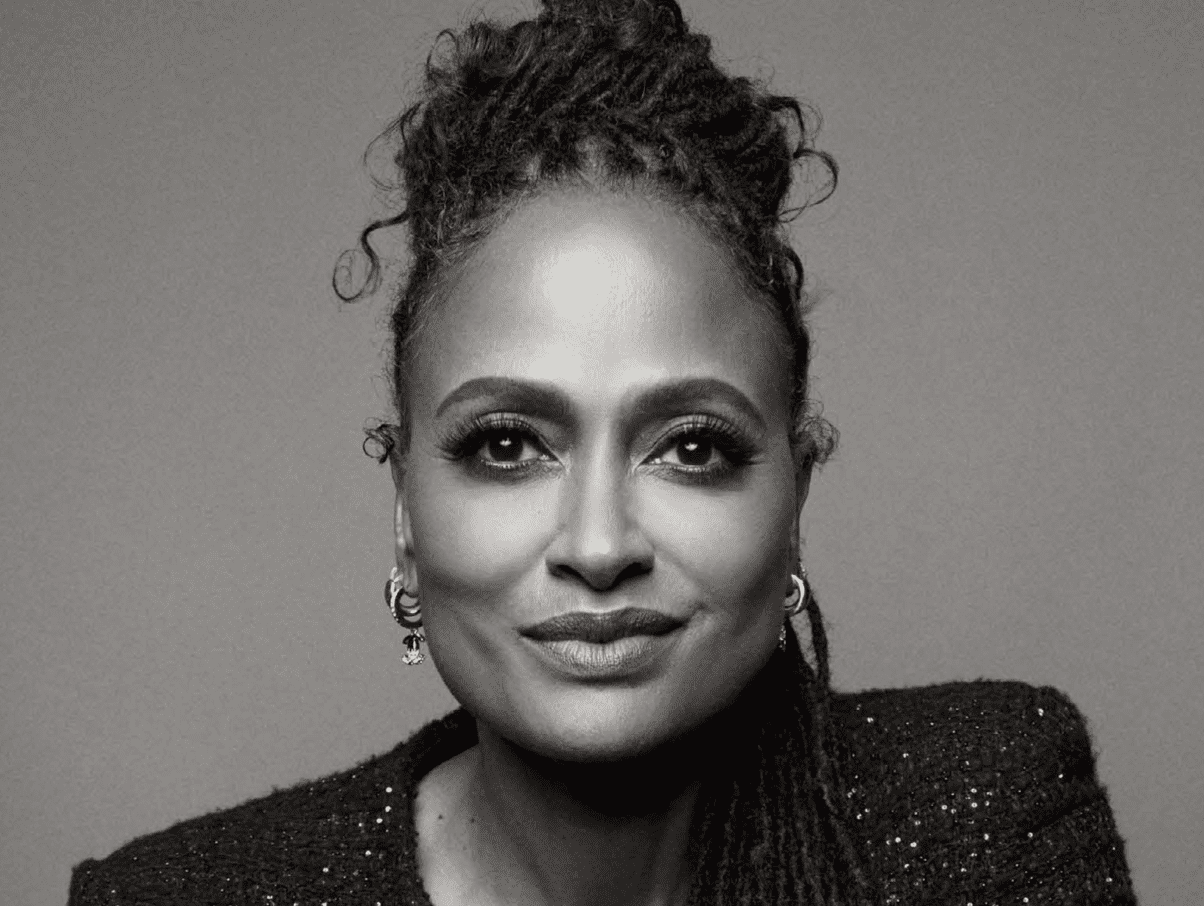

Ava DuVernay is a Hollywood trailblazer. The born and bred Angelino was the first Black female director to win Sundance (Middle of Nowhere) and be nominated for best picture at the Oscars and best director at the Golden Globes (Selma). It’s hard to believe she picked up a camera for the first time when she was 32, after years spent forging a successful career as a film publicist.

DuVernay’s dedication to lifting up others is indisputable. Her film distribution company ARRAY, set up after DuVernay’s debut feature film (I Will Follow) failed to acquire distribution, produces and amplifies the work of filmmakers of colour and women. In 2017, TIME magazine named her as one of the most influential people in the world. Devised by critics, the so-called “DuVernay test”—the racial equivalent of the Bechdel test—measures the scale of diversity in movies.

Much of DuVernay’s work explores injustices that have affected black communities—including Selma, a historical drama based on the 1965 Selma to Montgomery voting rights marches; drama series When They See Us, about the 1989 Central Park Jogger case; and documentary 13th, which highlighted the disproportionate mass incarceration of people of colour, and was called “the most important film you’ll ever see” by veteran civil rights campaigner Angela Davis.

Together, we discussed her love of filmmaking, empowering others, and the concept of destiny.

You started as a publicist and decided to become a filmmaker in your thirties. Do you feel there’s a time-frame for people to follow their calling?

Time is flexible and elastic. It can’t be confined, you know, and so when we have these artificial limits on time it’s just nonsense, but we allow ourselves to be governed by these societal constraints. When you’re in a state of desire, and in the crosshairs of Destiny, all these things can’t be predetermined or dictated by anyone other than you. That’s a miraculous, gorgeous thing.

Can you tell me about the moment you made that leap?

I never thought of it as a radical, out-of-reach idea. Certainly the mechanics of trying to become a filmmaker at that age without training was a challenge. But the mental gymnastics many people have to do to convince themselves to start was something I hadn’t wrestled with. My mother changed work in the middle of her professional career. She was a high ranking hospital administrator in the human resources department. Then, she decided to move out of California to another state and become a kindergarten teacher instead, which is what she wanted to do. I had that precedent that you can evolve into something else if you want to. So when I was on film sets as a publicist, I got interested in directing. It was specifically on the set of Collateral, by Michael Mann, a film I love to this day. I observed how he was shooting with digital cameras, and the cast was multicultural and diverse. It was right in my backyard in LA. They shot much of it in traditional communities of colour. I felt ignited by what I was observing and decided to try it for myself.

How can you deal with fear in a change like that?

Preparation is important. But so is learning, and much of what I’ve pursued has had to be learned. There’s no book. You have to actively do it, but at some point you either have to go to film school… or you have to pick up a camera and just start shooting—which is what I did. You have to get your hands dirty. How do you know you’re not competent at something unless you’ve tried?

When you were growing up you wanted to be a lawyer.

I committed to that for a long time. Someone asked me what I would grow up to be, I answered with that career, and then, well, ‘I guess I have to go to law school’. I’m interested in making sure people are treated fairly. Why isn’t everyone equal? And this opened up a number of other conversations in me. It’s a little pet peeve of mine [laughs].

How do you choose the projects you work on or the stories you want to tell?

Attraction. I’m fortunate that I’m not in a position where I have to take work-for-hire. I work with many directors who do that, and it can be beautiful, and encourage the chance for different stories. But I prefer to self-generate. I pursue stories I’m interested in dedicating my time and attention to, and I just go with my gut. It’s never a big calculation.

I was listening to you speak on a podcast and you said that you preferred to tell stories of triumph rather than trauma. What did you mean by that?

Every story I’ve told had a triumphant ending, success over adversity. And that’s kind of a through line of the stories. That’s true for Selma. That’s true for When They See Us. The subject matter is dense, but the end of both of those films are upswings. Look at 13th—I tried to end on a place where it’s not just challenging statistics or hard history. It ends with a question to the audience: What will you do? So I try to stay in that place, because a story expands the heart and mind, and gets you thinking about your place in the world, your behaviour, your history, and your future.

Do you want people to leave your films with a message of hope?

Not necessarily hope, but an energy of action. My films ask people to do something—be it within themselves or outwardly to the world—and it’s up to them what they want to do. My hope is that these pieces are not just seen and forgotten. Whether it is now or several years later, I want these films to get in your DNA and manifest somehow.

Why did you decide to set up your distribution company ARRAY?

I love necessity. No one was interested in distributing the work that I was interested in making, so it was about self-preservation. I looked around and other people were in a similar position. So, why not hold hands and help them do the same thing? Because I was a publicist before, I did know how to publicise and market a film, so with these two together, it was the bedrock of the idea for Array, and we’ve continued to grow.

Is it important to amplify the voices of people who are otherwise overlooked?

It’s important for me, but it’s necessary that it happens whether I do it or not. There should be spaces and avenues for people who are often left out of the machinery of Hollywood to participate in making movies and having them seen. So for as long as Array is around, we’ll do that to the best of our ability.

When was it you developed your love for cinema?

I was very young. My love for movies comes from a different vocabulary around film than some of my filmmaker friends who—I don’t know—have a lot of highfalutin film references from their early days. I was seeing movies at the mall with my aunt Denise, who was a lover of film, and we didn’t have access to foreign films or classics. It was whatever was playing at the mall, and that was often big-budget. But there’s magic there. It transported my imagination and made films my favourite pastime, and stories became my hobby. But I owe it all to aunt Denise Sexton—a registered nurse from Compton, California, the United States.

What was your favourite film as a kid?

I really loved musicals, particularly the original West Side Story. I remember seeing it at my aunt Denise’s house on a rainy day, and it was on television. I was spellbound by the colours and what I thought at the time were Latino actors. Turns out they were mostly in brown-face. But they looked, at the time, like people from my neighbourhood—and I love the story, the romance, the dancing, and I got lost in the magic of that film. It was my favourite.

Your aunt Denise sounds like a significant person in your love for the artform.

Yeah she was a loved family member who was kind of an oddball, who loved art, stories, and books—things that others in my family weren’t into. She bounced love off of those things onto me. She was unique. I look at myself and don’t feel particularly unique, because Denise was the trailblazer I looked at who would go to museums, book-signings, and concerts. Unfortunately many people who live in economically depressed areas like Compton only had one focus: their survival. That was my mother’s role and she worked very hard between jobs. But Denise didn’t have children, and so while times were also tough for her, she had time to pursue her love for art. It’s a privilege to be able to catch a movie or go to a museum. Many peoples’ lives don’t always include these things and Denise was the first person in my family who carved that time out for herself.

It blew my mind when you said in an interview you got a bad review of I Will Follow, which was based on Denise. The reviewer said it had an uncanny characteristic trait of a black woman who loved U2. But it was entirely based on reality.

To this day, it upsets me. And it wasn’t some small paper, it was the LA Times. Even if it weren’t a real story, the assumption that people of all kinds can’t be interested in all sorts of things is such a narrow way to live. To make these assumptions inhibits our understanding of one another.

How do you deal with negative reviews or comments like that?

I’ve had so many, but I have built thick skin. I’m no longer on Twitter but I was active for ten years, and when I look back, it gave me a certain connectivity—but the real thing it gave me was thick skin, because I read the most horrible, nasty, vicious things about myself. Now there’s not a lot that bothers me. Negativity is expected. I try not to let it become anything, and the same goes for the praise. It’s not just Twitter, that’s life. It helped me understand that it’s about subjectivity. Even me—I’m slow to criticise other filmmakers. If I see a film I hate, I won’t say anything because I know how hard it is to make a movie.

Was there a moment in your life where you became politicised? Perhaps as a kid, or while you were studying law at UCLA.

I would say UCLA. I would say Denise connecting me with U2, and U2 being involved in Amnesty International was the first time I started to think about rights and equity. That there were ways to combat things that were wrong in society. Going to Amnesty International concerts, becoming a member at thirteen-years-old helped me understand what was happening in different parts of the world…But it wasn’t until going to college where I started diving into African-American history that it took hold and became a big part of my life.

Let’s talk about Selma, which spoke to all of these things. You weren’t allowed to use Dr King’s original speeches because the film rights had already been purchased by another major director. How did you go about rewriting them?

What I tried to do was really listen to his cadence, the way he spoke and what he was trying to say. I followed the rhythm because I wanted David Oyelowo, the actor to be able to be Dr King, and so much of his thesis was his rhetorical power, the musicality to his voice. It wasn’t about translating what he was saying, but the way he was saying it. It took time, but it was a joyful process. Once I realised I had to do it, and we weren’t going to get the speech rights, I took great pleasure in people not knowing it’s Dr King unless they’re told.

There was a lot of hoo ha around the Oscars. While Selma was nominated for Best Picture, you didn’t get the Best Director nomination and David didn’t get his Best Actor nomination. Were you expecting that, based on the industry’s history?

I didn’t expect Best Director. But David, I really thought he had it and it broke my heart when he didn’t. It changes the career of a young actor. This young Black actor to get a nomination would have set him on a different path—but he’s done an incredible thing. This was his Destiny. But you know, if the film had been properly considered, and there were a bunch of reasons why it wasn’t, I wonder where it would have taken him. But he has such extraordinary talent that he was able to overcome that. The biggest thing I took from Selma was my friendship with him. He’s like a brother to me.

Do you believe in Destiny as a concept? It’s extraordinary that David randomly sat next to one of the investors on Middle of Nowhere on a flight, read your script, decided to star in the film, and now he’s a brother to you…Is that Destiny?

Yeah I believe in Destiny. We were destined to meet. These things are not manufactured on our own. I think that if those moments hadn’t happened, there would be no Selma, no relationship with him, the person who fortified me and fed me in so many ways. This is a human being who is an artist. I think it’s all in the stars.

Do you think your time as a publicist helped your career as a filmmaker?

Sure. I felt confident that any film could be sold and shared. It gave me the confidence to make my early works about, you know a black woman in Compton whose husband is incarcerated, who works as a nurse and takes the bus to see him [Middle of Nowhere]. It’s something that probably people wouldn’t think would win at Sundance—nothing like that had won before it did—but the film went on to launch a career. So yes, I knew how to publicise it. I knew I could bring people into the theatre. That’s the biggest gift my previous career gave me: the confidence to tell any story; which is a big worry for many filmmakers. They allow people to tell them their ideas aren’t marketable. I didn’t have that.

You’ve said in the past that there’s a difference between passion and desperation, and that we all ought to be passionate and avoid being desperate. Is that something you still believe?

There’s this psychologist called Esther Perel, and she was talking about desire. That Attraction plus Obstacle is Desire. And I remember hearing that and thinking, ‘Oh that’s filmmaking.’ Creativity is Attraction. Then you add Obstacles: which is every part in the movie-making process. All of this equals Desire, and it made me realise that it’s not just Passion actually—but Desire. The Attraction helps you acknowledge the Obstacle. Desire is seeing the Obstacle and saying, ‘I want it anyway.’ That’s pretty powerful—as opposed to going, like ‘I’m passionate, I want to do it’. There are going to be obstacles, and that’s what filmmaking is all about.