For St Patrick’s Day, we revisit the best cinema of the Emerald Isle.

Traditions can move fast. Centuries ago, Paddy’s Day in Ireland was a quick break from Lent to thank an elderly man for driving the snakes out of Ireland. Now, we’re a cultural superpower, watching the world (mostly Americans) wear shamrocks, drink green shots and savour the surprisingly upbeat music of the IRA.

Has the tradition fallen? Not really. I’d simply like to urge you to do something a little different. Because as Ireland’s influence has risen, so too have our stories (see our recent Oscar nominees). In an effort to appease our original Patron saint, I’d urge you to give our films a go and enjoy a side to Ireland you might not yet have witnessed.

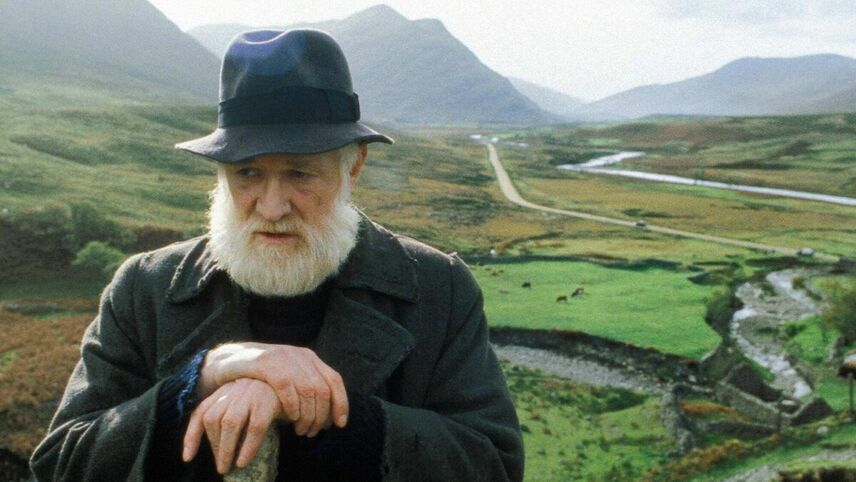

Not all Irish movies are depressing. Some are so dark they become liltingly comical. Jim Sheridan’s highly serious adaptation of the melodramatic John B.Keanes play of the same name is one of these beasts, following Farmer Bull McCabe (Richard Harris) is locked in a land dispute with Irish-American businessmen. The callous plastic paddies don’t really understand why Bull is particular about this field. Only the legacy of starvation and the bullying, alcoholic paunch of Harris could defend the meaning of turf believably—and lead a film to such a depth that you want to cry and guffaw by the close. Fierce watch.

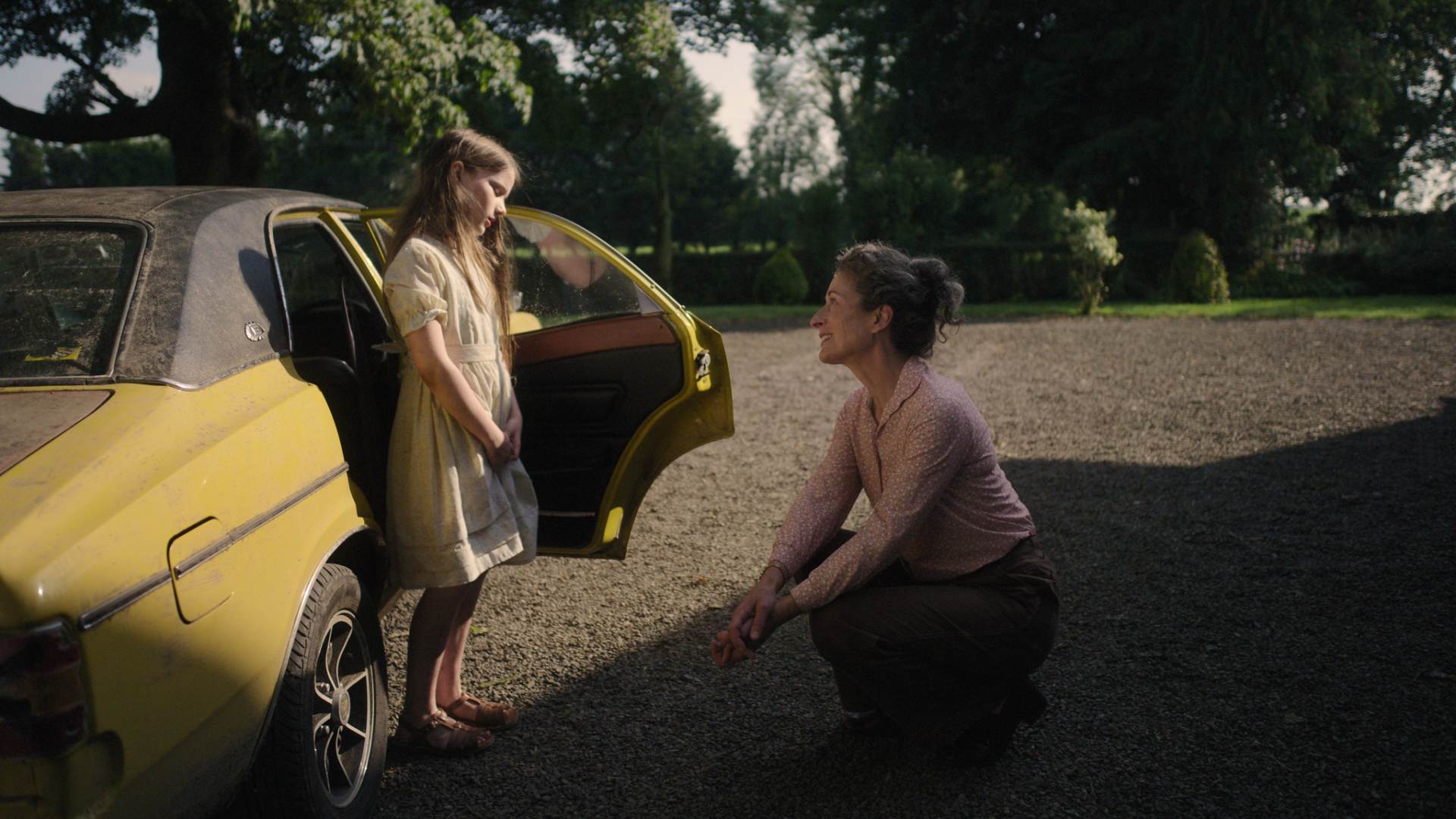

Translated in English as The Quiet Girl, Colm Bairéad’s short-running feature retreads a typical Irish premise: a withdrawn Irish girl spends her summer on a remote Waterford farm staying with distantly married relatives who teach her an older, romanticised way of life. The film’s rural setting is played up lovingly (helped by an unrushed, almost lethargic, cinematography) and the small central cast create a tight-knit feeling of community complete with typically prosaic Irish homilies (“It must have been some head of cabbage they found ye under,” is a fairly standard insult). If The Field put you off rural Ireland for good, An Cailin Ciuin is enough to gently beckon you back to prairie.

Waking Ned takes a novel image—a dead man holding a winning lottery ticket—and spins it into a comedy of manners on mischievous lawless opportunism. Set in the sleepy village of Tullymore, the film follows two old rogues, Jackie and Michael, as they scheme to claim the lost lottery prize, enlisting their fellow villagers in a quiet conspiracy.

A surprising box office hit when it was released in 1998, Waking Ned is a joy: keeping the wry humor of a tall tale told over pints, with a streak of gentle rebellion that keep both its leads irresistibly charming. The landscape is gorgeous, the wit is dark, and the moral compass—well, it wobbles just enough to keep things interesting.

There are many film adaptations to books in Ireland. We’re good at it. We’re also good at tying your guts with guilt. Lenny Abrahamson strips Kevin Power’s Blackrock-set novel down to its raw bones: Richard, a charismatic, well-off teen rugby player, has everything—charm, talent, a bright future—until a drunken night spirals out of hand. An unflinching look at privilege and the quiet unraveling of a golden boy.

There’s no melodrama or easy moralizing to the film—just a creeping sense of inevitability as Richard struggles to reconcile the version of himself he projected with the truth of what he’s done. If you’ve ever thought you’ve got it wrong drinking, this tightly wound thriller will reassure it could always be so much worse.

Naked, pale, hungry—McQueen’s arresting images of Belfast’s starving prisoners standing before uniformed guards shocked cinemagoers when it was first released. Following the real hunger strike of IRA bomber Bobby Sands, McQueen’s feature sides with the underdog, but takes careful moments to paint humanity on both sides of the divide. Of course, it’s not just the director that gives this painfully arresting critique the pain it needs to keep his drama moving: Michael Fassbender’s portrait as Bobby Sands slowly reduces Sand’s rage and rebellion to something almost painfully gentle.

Fancy something shorter? Roisin Agnew’s slick 2024 short documentary focuses on a lesser known aspect of Northern Ireland’s troubled history: how the British government banned broadcasting the voice of any figure associated with the IRA, with television or radio studios simply dubbing over the clips with paid actors. This shrewd doc examines the role of voice, authority and the creeping parallels of the British government’s modern day government’s interests between protest and media.

If you haven’t guessed, Ireland loves two things: an underdog and total tragedy. Anglo-Irish actor, Daniel Day Lewis bucks that last trend and plays Christy Brown: a real man from Dublin who—despite being born with such severe cerebral palsy—manages to become an artist. There’s little in the way of patronizing sympathy in Sheridan’s film, but just the simple facts of Brown’s life from beginning to end as he navigates it with humor. Typical of Lewis’s method acting (which included remaining wheelchair bound for the film), Lewis throws himself into the role of Brown’s situation with such grace that the film’s feel-good motif of stubbornness, pride and resilience stitches a smile to your face.

“Every word of Irish spoken is a bullet fired for Irish freedom,” are not words many expect to hear from a middle-aged man teaching their children their language—but by God, Fassbender delivers it to his two young boys like a champion. Famed for adding a punk flair to the old-fashioned Irish language, the young Belfast rap trio Kneecap first exploded into fame with Irish-language songs that celebrated raves and proudly mocked British history. Credited for bringing Irish-speaking culture into the 21st century, this comedy about the band takes a healthy dose of artistic licence and recreates their transition from disenfranchised teens to Irish rap icons with a madcap mix of thriller and comedy. Keeping all the gallows humor of their Belfast setting (and, I believe, fairly regular lines of ketamine), this comedy revels in their home city as a carnival of intolerance, craic and violence where language is just another political game. If you’ve ever enjoyed the listless musical energy of People Just Do Nothing, you’ll like this.

We’re going quite heavy into Northern Ireland on this film list (mostly because there’s a lot of cracking films, and which person hasn’t seen The Wind That Shakes the Barley or Banshees yet?). Neil Jordan’s sleazy, pulpy mess of a thriller The Crying Game took home Academy Awards, Oscars when it debuted in the 90s and even briefly ranked as the BFI’s 26th greatest British film of all time (which is a bit of a hard sell when your topic is killing British soldiers). What’s the appeal? It’s hard to unpack the movie’s twist without spoilers, but beyond simply being an achingly gorgeous film with hardboiled pacing, all I’ll say is you’ll be asking questions about politics you might not have expected in an IRA drama.

Can a movie be rescued by its final ten minutes? If you’re on the fence, I’d recommend watching the legendary John Huston’s impassioned adaptation of Joyce’s final tale in the Dubliners short story collection clocks in at 83 minutes and follows the bookish Dan Brown as he navigates a labyrinthine, slow dinner party that culminates in a confession that’s one of the best odes to life, love and death in film or literature. Huston — who would die shortly after the film — directed Joyce’s short story on an oxygen tank, having learnt the film’s moments almost by heart and shipping an entire cast of Irish actors to America to keep it feeling authentic. His daughter, Angelica, comes into the limelight in one of her first major films: taking the baton from her father with a haunting quality that, I like to think, was one of the reasons this little known gem is among Akira Kurosawa’s favourite ever films.

There’s so much beauty to Huston’s final few moments as the plot finally unfolds. What was once uneven, even staid, shifts with the weight of a ghostly confession. But there’s no novelty: what Huston captures is the best of Joyce: a slow, supernatural revelation that feels mundanely universal. It’s a fleeting, transcendental moment in Irish cinema. And a perfect end to one of its best chapters.