“Predicting literary trends is a bit like predicting the weather.” We asked the author Lucas Oakeley to make sense of where books are heading in the future, from short stories to translated fiction.

Do you ever think about the future? I do. Sometimes I’ll stare at my partner and try to imagine what she’ll look like when she’s 90. How deep the grooves of her crow’s feet will run. How gnarled her knuckles will get. How beautiful she’ll still be, wrinkled like a walnut, in every conceivable way.

I try to avoid thinking too much about things such as the impending climate crisis or the arrival of our AI overlords because they really bum me out, but I’m always asking myself what the future of publishing looks like. Why? Because I’m an author. And that’s the sort of question, along with “how many commas is too many?” and “why the fuck do I do this again?”, we ask ourselves a lot. Figuring out what readers are going to be reading in a year (or two or five) is one of those unsolvable existential quandaries that’s capable of keeping me up at night. I know that’s somewhat shameful to admit as an artist—and we’re all supposed to be motivated by a more divine muse than the shelves of Foyles and Waterstones—but I’m sure it’d make you lose sleep, too, if it were going to directly impact whether or not you’d be able to pay rent in the future.

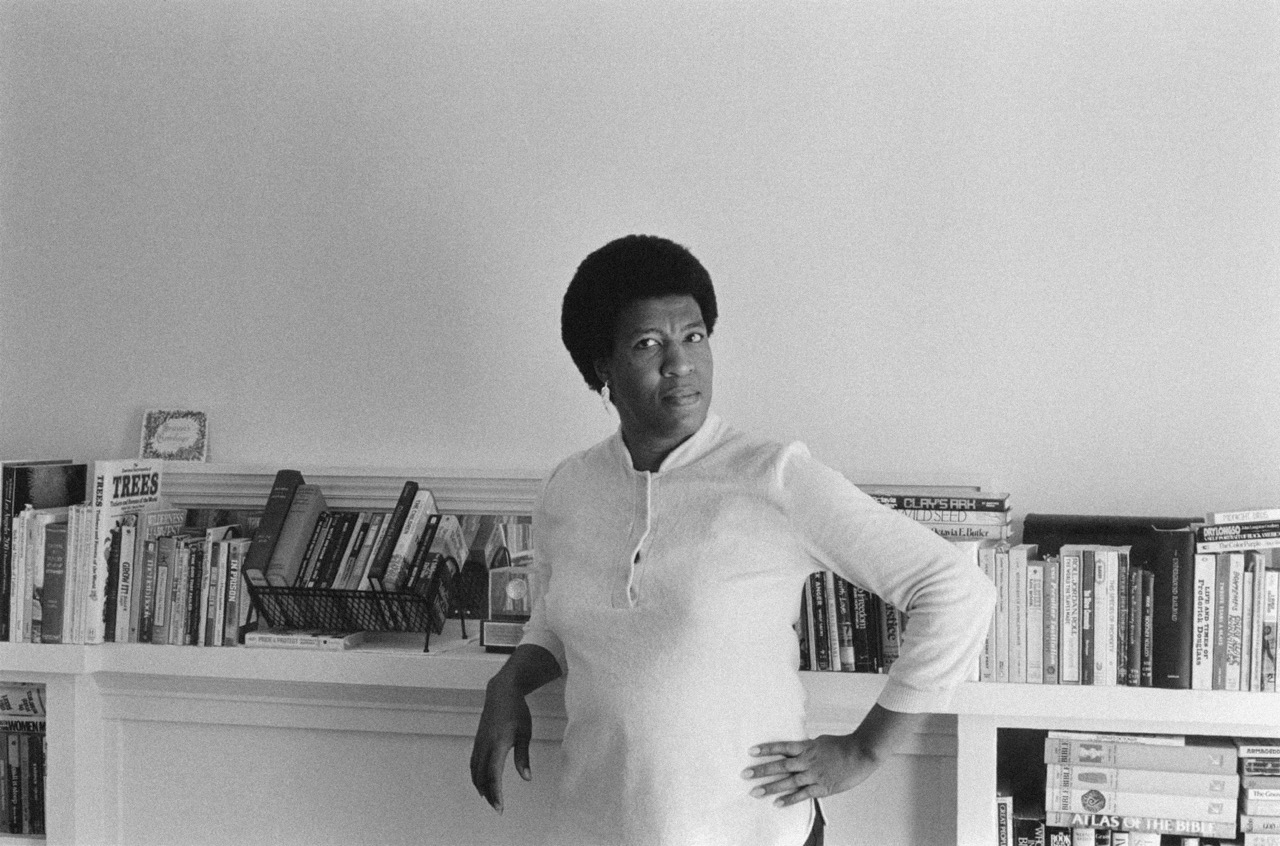

Ursula K Le Guin, 1970s. Courtesy of University of Oregon Libraries.

Predicting literary trends is a bit like predicting the weather. Except there aren’t any apps or websites or even chicken-shaped weather vanes telling you what the chances of rain are. All you’ve got to rely on is squinting at the sky and trying to parse a message through the clouds. When it comes to fiction, it can be difficult to tell what’s going to take off when there are so many variables involved. The publishing industry can move at what seems like a snail’s pace but as soon as you turn your back on it, it’ll be halfway down the M4. It’s also hard to know what a trend is, or what readers are really reading, until you’re a few years past the apogee of the hype and able to look back in your wing mirror at the wreckage of romantic novels and enemies-to-lovers narratives behind you.

I’m not claiming to be a clairvoyant or a soothsayer, but I am a big reader. And a writer. And I do talk to other readers, writers, and publishing experts on a regular basis. So if you’ll allow me to stare into my crystal ball for a few seconds, I’ll gaze into the mist and tell you all about the literary trends of tomorrow…

Given how fried everyone’s attention spans are, it doesn’t feel like a stretch to suggest that short stories, novellas, and experimental forms of tight, pithy fiction are going to become sought-after in the near future. To put it simply: there will be more “less” writing. Which, like most trends, is just as much an innovation as it is a rummage into the past.

Writers such as Raymond Carver and Alice Munro made their entire careers on the back of their short stories. In between novels, F Scott Fitzgerald noodled out 164 short stories for various publications. In 1931 alone, he earned nearly $40,000 (approximately $852,568 in today’s money) from a flurry of short stories he wrote in manic succession. I don’t think we’ll ever see anyone as prolific (or as profitable) as Fitzgerald again; however, I don’t think it will be long before we see the next great writer who deals exclusively in the medium of brevity. Authors and publishers alike are more open to compressed fiction. Samantha Harvey’s slim, serene Orbital (2023) took home the Booker last year, and writers such as Claire Keegan and Natasha Brown have seen significant critical and commercial success with their sub-200-page novellas. Next year will also see the arrival of The News from Dublin, the latest short story collection from Colm Tóibín.

The greatest indicator of a sea change, to me, was the publication of Eliza Clark’s She’s Always Hungry (2024)—an easily digestible short story collection, tied around the theme of destructive appetites, which exists as a complete work in its own right as well as a handy stopgap between novels to keep readers satiated. The novel to short story collection to novel sandwich is going to be an increasingly enticing option for agents and publishers keen to keep an author in the spotlight without spreading their creativity too thin.

What to read:

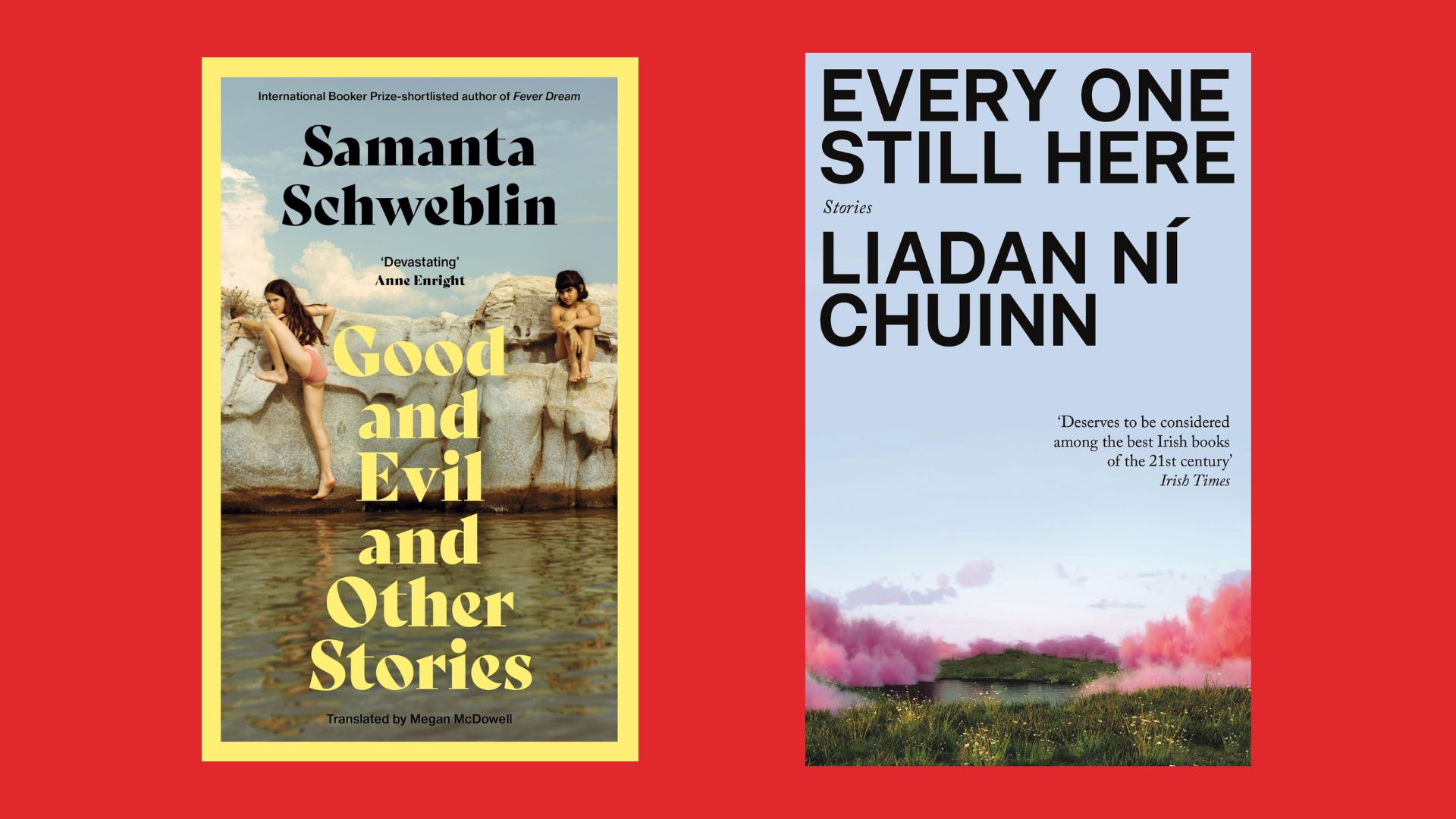

Liadan Ní Chuinn—Every One Still Here (2025): Liadan Ní Chuinn is an anonymous writer with a distinct voice. This, their debut, is a deft collection of short stories set in the north of Ireland.

Samanta Schweblin—Good and Evil (2025): A lean and unsettling collection of short stories from the phenomenal Argentine author. All the stories in this collection are thematically linked, leaving the reader with a sinking sense of dread.

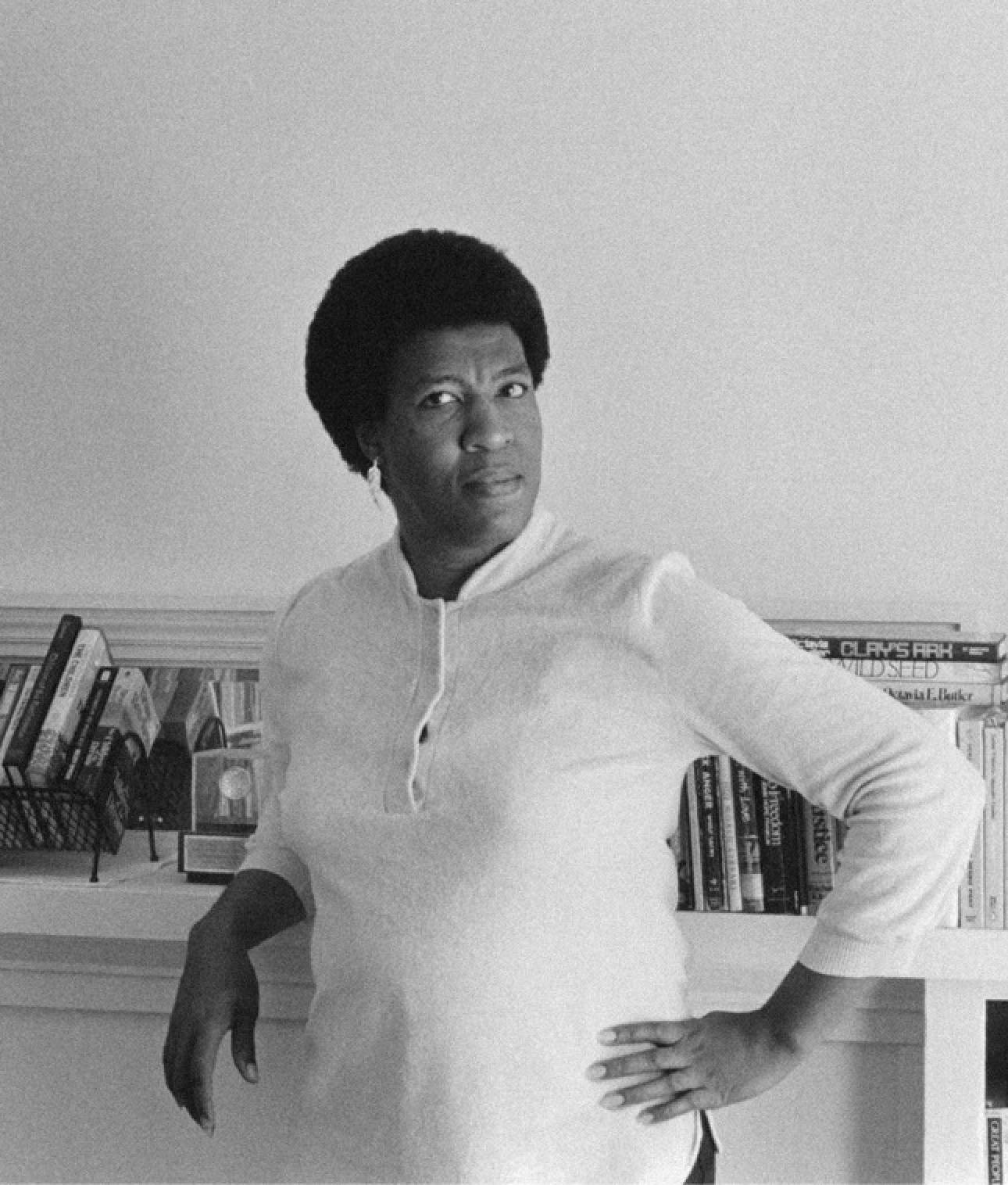

Author Alice Munro, 1983. By Nancy Crampton.

Translated fiction isn’t new, but the desire for it in the Western world seems to be reaching fever pitch. Fitzcarraldo Editions is an independent British book publisher that specialises in literary fiction, primarily works in translation. Walk into any bookshop and you’ll see the uniform International Klein Blue of its covers taking up space on the shelves. With its striking aesthetic—and what seems to be a delightfully simple rationale of “If it’s good in Polish, it’ll probably be good in English”, which I’m aware is a glib assessment of what must be an incredibly complex process, but still—Fitzcarraldo has a strong track record of engaging readers and scooping up prizes. The appetite for translation isn’t just alive, but thriving. The amount spent by readers on translated fiction print books in the UK continues to rise year on year, and the publishing industry has taken notice. Just this year, the South Korean author Han Kang became the first Asian woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. And there’s perhaps been no better example of translated fiction hitting the mainstream than the success of Asako Yuzuki’s unavoidable novel Butter (published in English in 2024).

Crowned Waterstones Book of the Year 2024, Butter has sold almost half a million copies in the UK, a striking statistic considering it sold less than that in Yuzuki’s native Japan. The same can be said for Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection (published in English in 2025), a Fitzcarraldo find, which has sold more in English than it did in Italian by a significant margin. In fact, Perfection made as many sales in a month in the UK as it took three years to make in Italy. Yuzuki’s latest novel, Hooked, is set for publication in early 2026, and I’d bet good money that editors and publishers all over the country are scouring their inboxes for the next Butter at this very moment.

What to read

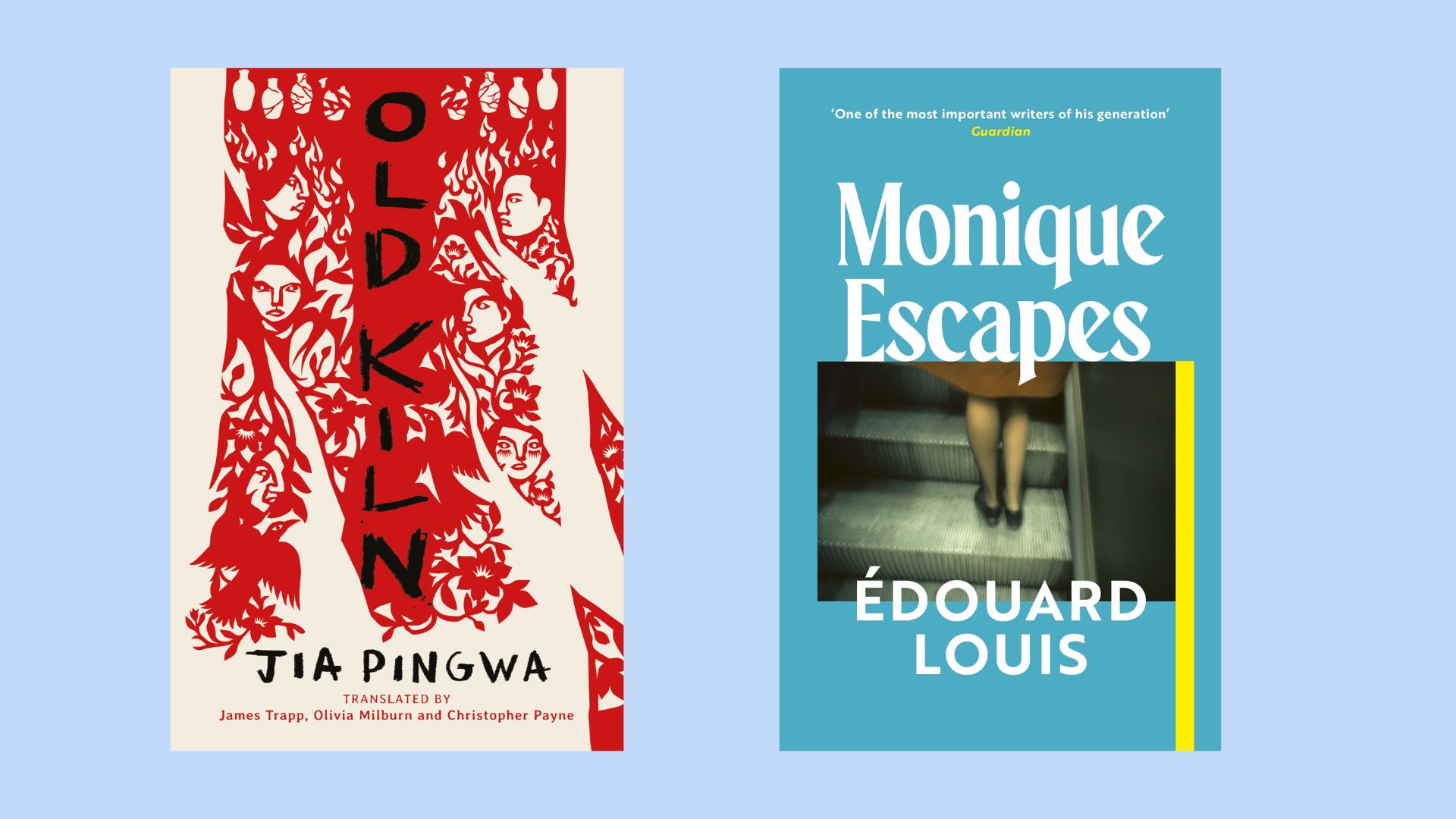

Jia Pingwa—Old Kiln (2025): A big, thick tome of a book, which was translated into English for the first time this year. Pingwa’s epic is about the residents of a small village, set during the Cultural Revolution in China.

Édouard Louis—Monique Escapes (2026): All of Édouard Louis’s writing is pitch-perfect. His latest, which will be published early next year, tells the story of his mother’s escape from an emotionally abusive relationship.

I’m naturally sceptical about the coining of new genres because they can feel like the literary equivalent of putting lipstick on a pig. The latest shade being paraded about is the term ‘new adult’. Essentially an extension of the young adult fiction category, it’s picking up traction in the publishing world and is currently being used to classify any writing that deals with… well, I think it’s something to do with growing up? Dating around? It’s a bit vague, to be honest.

Its creation was far from organic, too, coinciding with the launch of The New Adult Book Prize—an award launched by The Bookseller in partnership with the Times and Sunday Times Cheltenham Literature Festival. What classifies as new adult fiction according to the awards body is “fiction that explores the lives and challenges of people aged 19–29”. A group of people formerly known as ‘adults’.

It’s nothing but a harmless moniker, of course; however, supply must rise to meet demand, so don’t be surprised if we see even more novels written about (and specifically aimed at) individuals within that new adult age bracket.

What to read

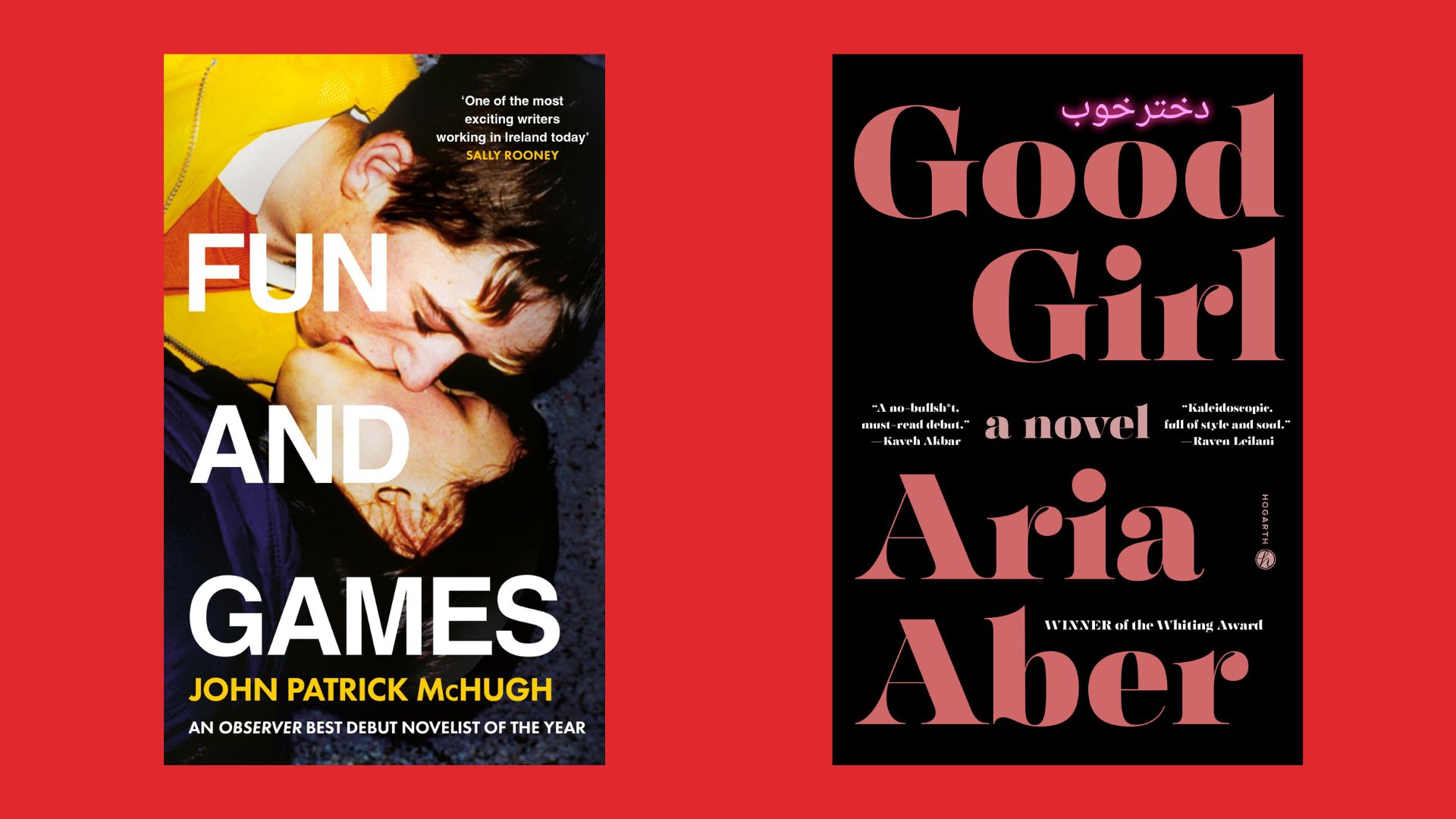

Aria Aber—Good Girl (2025): Shortlisted for both the Women’s Prize for Fiction 2025 and The New Adult Book Prize 2025, Aria Aber’s novel is a beautiful, heart-wrenching coming-of-age story set in Berlin.

John Patrick McHugh—Fun and Games (2025): A punchy, raunchy debut novel that follows a teenage boy as he comes to grips with love, life, and Gaelic football on the west coast of Ireland.

We’re in a golden age of horror. With the ballistic boltgun of a film like Weapons (2025) and the Cronenberg-y body horror of The Substance (2024) not just cleaning up at the box office but becoming bonafide cultural moments, it’s hard to ignore the spike in demand for gore and violence.

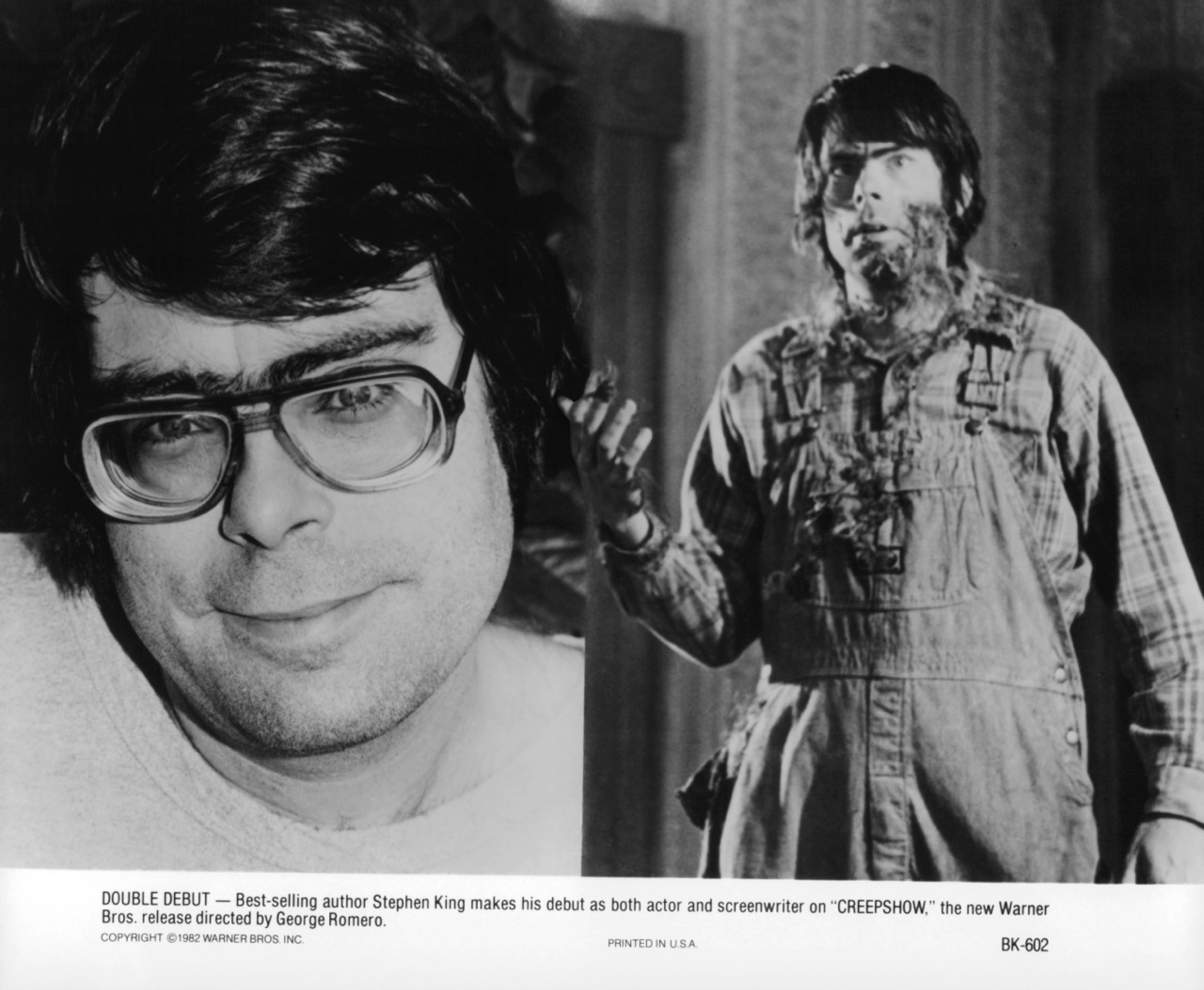

There’ve been as many as five (five!) big-screen adaptations of Stephen King works released in 2025, and despite just how fucking much he’s written, Hollywood’s going to need some new intellectual property to mine at some point. Luckily, we’re experiencing a horror writing renaissance with record-breaking sales and a broader appeal than ever before.

Between 2022 and 2023, sales of horror and ghost stories rose by 54 percent in value to £7.7m, and there’s nothing to indicate we’re going to see a plateau in interest any time soon. In the first three months of 2024, sales were 34 percent higher than they were in the same period the previous year. The masses are baying for blood, that much is obvious, but the resurgence can at least partly be attributed to the rise in the number of horror writers from marginalised communities who are bringing fresh perspectives to the field. New voices mean new readers, and an influx of new readers suggests the future of horror is in safe hands.

What to read

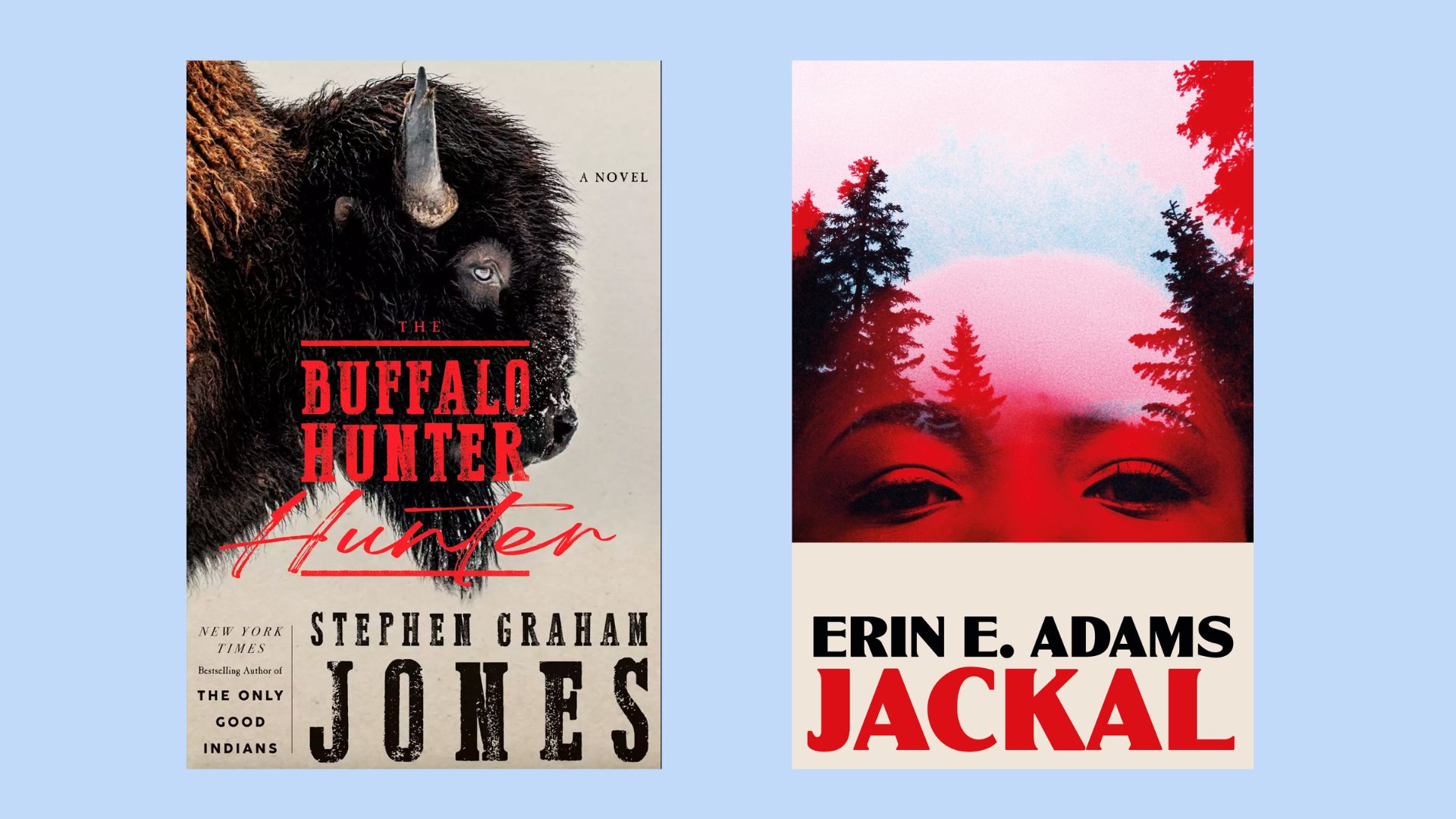

Stephen Graham Jones—The Buffalo Hunter Hunter (2025): A highly entertaining, whipsmart novel about an indigenous vampire in the Wild West. Bloody. Brilliant.

Erin E. Adams—Jackal (2022): The set-up? A young Black girl goes missing in the woods outside her white rust-belt town. The delivery? Sublime.

Stephen King in Creepshow (1982). Courtesy of Michael Ochs.

The way writers depict the future is going to take a hairpin turn. Dystopian fiction has become too easy to write. Too easy to imagine. Too easy to witness. Why would you want to write or read about how terrible the world is when you can turn on the news (by which I mean look at your phone) and have your worst fears made reality in a matter of seconds? What sort of unrelentingly bleak dystopia are you going to have to construct when people are getting arrested on the street for peacefully protesting a genocide? It’s impossible to read a book like Atlas Shrugged (1957) and digest Ayn Rand’s philosophy of “rational self-interest” without being reminded of Donald Trump’s obsession with free-market capitalism and his brand of uniquely American selfishness. And it’s not so much a leap but a meek shuffle to get from the social-media-saturated world we inhabit—where nearly all of us get our daily dopamine fix via identical Apple products—to the crass brand reverence in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and the incapacitative impact of the happiness- inducing drug ‘soma’.

What’s becoming a growing trend, instead, is books about the future that aren’t necessarily set in a bucolic post-climate-crisis or utopian world, but are willing to go beyond the low-hanging fruit of “everything is fucked”. There’s a demand for narratives that don’t just tell people how bad things are going to get, but actively prepare them for how to adapt, survive, and eventually thrive in the future.

Novels such as Always Coming Home by Ursula K Le Guin (1985) and Huxley’s Island (1962) are classic blueprints for this new wave of writing, inspiring contemporary authors to write similarly futuristic novels that combine urgency with constructive hope. Because, sadly, in today’s day and age, hope might just be the wildest thing to imagine.

What to read

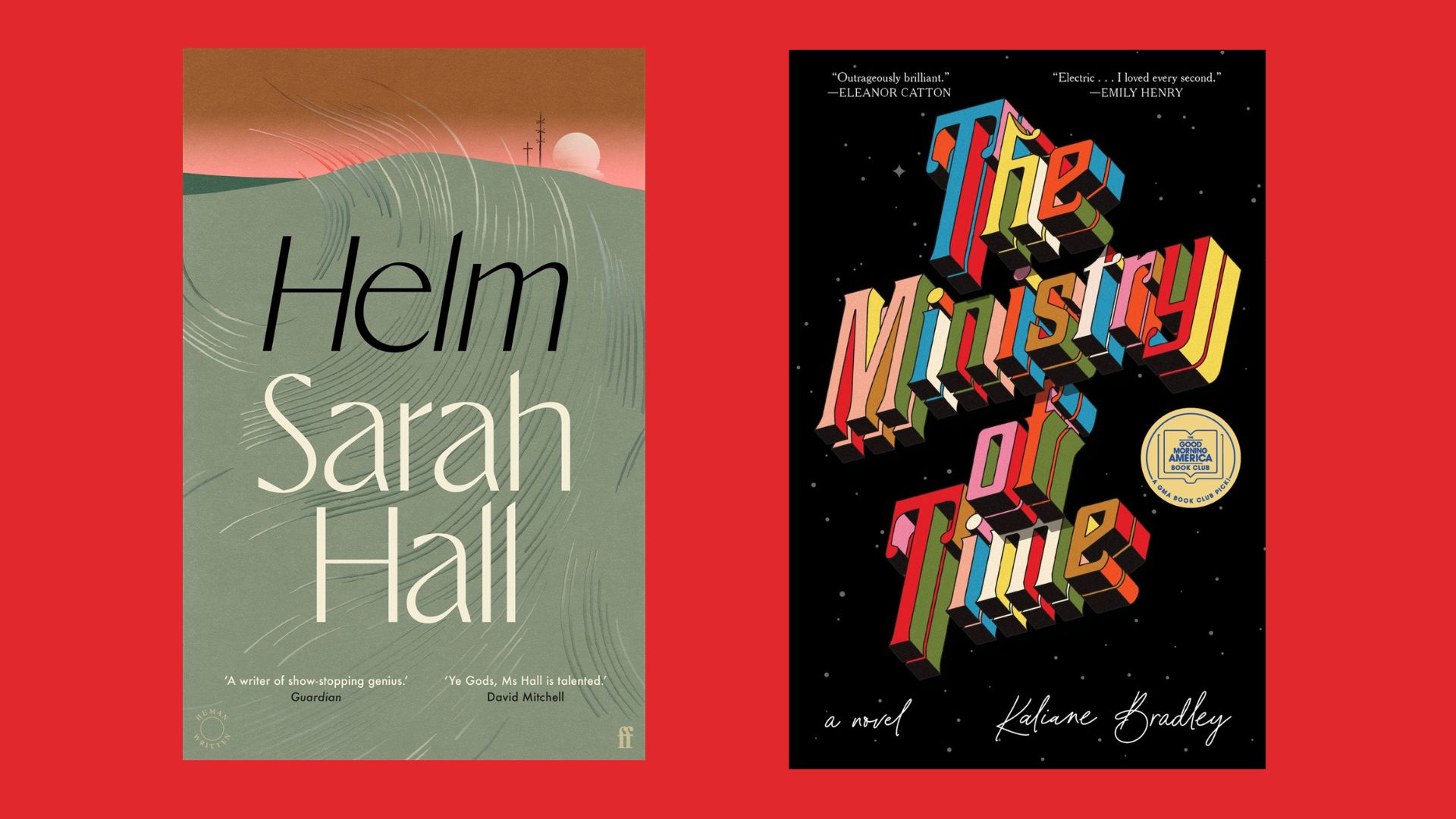

Sarah Hall—Helm (2025): A lush, multi-era narrative that deftly explores humanity’s relationship with nature. It’s not all sunshine and rainbows, but it’s a novel that provides space for readers to reckon with ecological change without surrendering to despair.

Kaliane Bradley—The Ministry of Time (2024): This debut novel is a funny and uplifting time-travel romance set in a near-future UK. An excellent yarn.