“The workshop is not just a place in which to receive and provide feedback, but a place in which a relationship–or several relationships–between the writer and his work, between the writer and the workshop, and, most importantly, maybe, between the writer and his own psyche and ego–is formed and unpacked.”

Ramzi De Coster looks back at his time on an MFA program at Columbia University, analysing the central importance of the ‘workshop’ to make—and break—a writer.

Long before I went to graduate school, I tried to talk myself out of wanting to become a writer. Not being a writer, or becoming one, but wanting to become one–an important distinction. Being a writer had to seem unattainable to feel real. That was the great contradiction at the heart of the dream. The fiction writer was something sacred, mythic, the result of a small miracle–and also something you could ostensibly become, or learn to become, with an MFA. Then I came across these words, half-joke, half-lament, entered into an online thread by someone who had presumably thrown in the towel: “It’s like hitting the slot machines in Atlantic City at 4:00am, everyone’s desperate, very few people win, and the game is definitely rigged.”

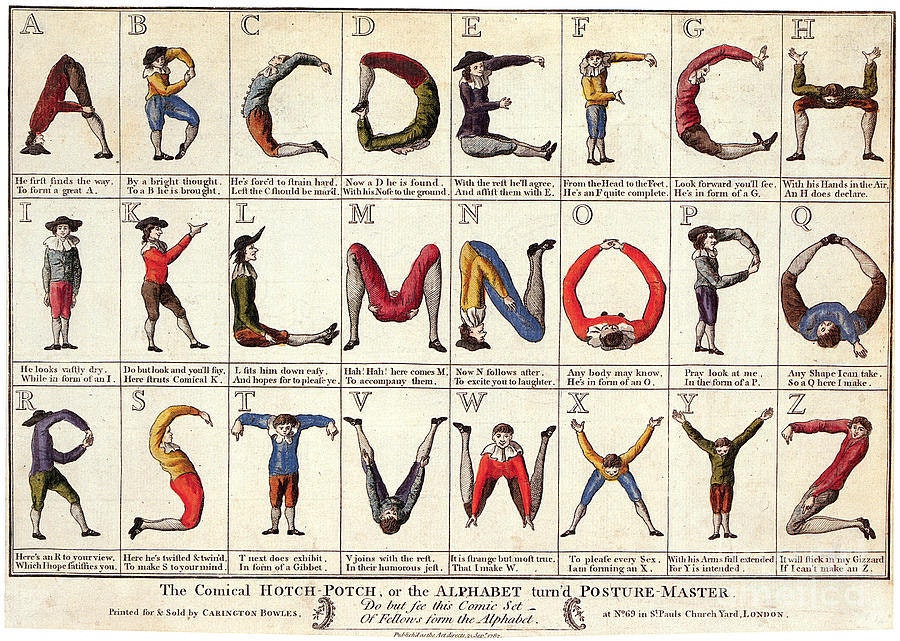

That was the first of many metaphors that would stay with me when I began the MFA in Writing program at Columbia University, in the fall of 2017. Novels became houses; short stories, rooms. Workshops were battlegrounds or stages. Great stories were well-balanced dishes with ingredients that blended well.

Hope was always laced with doubt. What are you going to do with that? Will you be any more of a writer after? Is it even possible to learn to write? Can I really do this at all? I didn’t have a good answer to any of these questions and I remember sitting in a classroom as we went around the room, on the first day of the first semester, describing what it is we write and why. As my turn to speak neared I realized, anxiously, that I’d entered the program under a misapprehension. I thought the point of coming here was to figure that stuff out, yet everyone to the left and right of me had these practiced yet interesting responses. Because I didn’t have a good answer I made one up on the spot, and the professor’s perplexed face—searching look, slightly opened mouth, flexed brow—as I rambled incoherently is seared into my memory. Sitting in a classroom next to the heater a couple months later, watching the snow fall in sheets over Morningside Heights and accumulate on the lawn and over the buildings, I began to question why I’d come here, or, more importantly, what I’d get out of it if I stayed.

For many writers, the notion of not “making it,” of not materializing the dream that rages at the back of their minds, is hard to fathom. It turns the workshop into a pressure cooker, piles onto it a heavy emotional weight that hangs like wet clothes on a line. That’s what, I felt, could be detected in the very subdued but fraught air of the musky, dim-at-noon rooms where we congregated, once a week, to critique each other’s work. Sometimes, this tension manifested quietly in people’s facial expressions as they received feedback: the flash of anger at an unwelcome narrative suggestion or the shell-shocked look on a peer’s face after forty minutes of criticism, harsher than it needed to be. Other times, it found its voice, like when a shouting match erupted and a student stormed out, or the word “nonsense” stilled the room over a piece that rambled philosophically for twenty pages, or the familiar end-of-workshop defense sounded again: “I know what you mean, but this happened in real life,” or “I know it needs work, I wrote this quickly.”

For many writers, the notion of not “making it,” of not materializing the dream that rages at the back of their minds, is hard to fathom. It turns the workshop into a pressure cooker, piles onto it a heavy emotional weight that hangs like wet clothes on a line.

MFA programs vary in many ways except one: the workshop is everything. Workshops themselves change, but they typically go like this: You sit in silence (this is mandated), while other writers critique your story, which, having otherwise materialized in a vacuum, is suddenly laid bare on an operating table. First the “what’s working.” Then the “what needs work.” At this point, your mind has already simplified this into an obvious but immature binary: the good and the bad. But it’s also starting to awaken in you the realization that the workshop is not just a place in which to receive and provide feedback, but a place in which a relationship–or several relationships–between the writer and his work, between the writer and the workshop, and, most importantly, maybe, between the writer and his own psyche and ego–is formed and unpacked.

A work-in-progress bears all the hallmarks of a typical relationship: the early courtship where writing is fun, enjoyable, and full of anticipation because blank pages are being spontaneously filled with ideas and characters and settings that feel like they’ve emerged from some remote, faraway place, making them mystical and alluring. You’re just going with the flow. Then, further along, the initial revision and editing takes over and the true nature of that relationship is put to the test. Ideas, perspectives, and dynamics that once seamlessly inhabited the same universe no longer appear compatible. Something is clearly off, but you’re not sure what it is. So the work-in-progress is submitted for workshop and the scaffolding over the foundation you built begins to buckle in real-time. A room full of strangers point out structural deficiencies while you sit, in silence, taking notes and wondering how it came to be that this semi-spontaneous act of creation now just seems plainly terrible and embarrassing and a failure. What was perfect in your mind wasn’t perfect at all, it turns out. And because your work is deeply personal and an extension of you, then this must be a reflection on you as a writer and as a person. But maybe you knew that all along. In fact, you did, and in hindsight, you can see how, without realizing it, you were writing for an audience, modifying your work, withholding, trying to seem clever, trying too hard to experiment, trying to imitate so that this audience you knew would read your work would like it. And so this relationship, under workshop scrutiny, breaks apart, and you’re left with the simple realization that what you ought to do is write what you really want to write, without any embellishments or concealing, because though writing can be anything, good writing must, necessarily, be honest.

So you inevitably go through a kind of personal reckoning in pursuit of the idealized version of your fiction, confronting the reality that perfection is ultimately unattainable–the work is never exactly as you imagined or hoped or dreamed it could be. And it certainly won’t be received the way you want it to be—that would betray the point of a workshop. But something else happens in a workshop that never does in an otherwise solitary art. You realize that writing, or the experience of writing, has all of a sudden become temporarily collective. Everyone else is experiencing the same angst in the same space, wrestling with their egos in the same way, defending them from each other but also, more importantly, providing essential encouragement.

Throughout my time in the MFA I learned to see it as a place in which to get everything out, whatever that meant. So, I wrote stories that went nowhere, stories I thought were good but were in fact bad, stories I thought were bad but turned out to be good. I wrote several stories multiple times, trying to reach for the heart of something but finding that my fingers closed on air every time.

Throughout my time in the MFA I learned to see it as a place in which to get everything out, whatever that meant. So, I wrote stories that went nowhere, stories I thought were good but were in fact bad, stories I thought were bad but turned out to be good. I wrote several stories multiple times, trying to reach for the heart of something but finding that my fingers closed on air every time. I tried my hand at speculative fiction, realism, surrealism, a blend of all three. I struggled to find my voice, sometimes I wrote declaratively because doing so had worked, once. On other occasions, I reverted to overdone lyricism that swore off sentence breaks. I wrote a story that one professor “couldn’t get into,” but that another praised in a way that has stayed with me since.

What I probably didn’t realize at the time but do, in hindsight, is that this willingness to abandon the ideal of perfection, to try everything and make mistakes, was enabled by having to sit silently, as in a ritual—one that has more to do with the writer than the writing–while people pull apart, discuss, and argue over your work to ultimately leave you with what seems integral and inherent to writing fiction in the first place: the absolute uncertainty of where to go next. George Saunders, describing the merits of being in a workshop, said it better than I could: “…the process is still a noble one—the process of trying to say something, of working through craft issues and the worldview issues and the ego issues — all of this is character-building, and, God forbid, everything we do should have concrete career results. I’ve seen time and time again the way that the process of trying to say something dignifies and improves a person.”

In 2020, after the program came to an end, I found myself thinking a lot about the classes where, not critiquing each other, we turned already-written stories the literary world considered great, like James Baldwin’s Sonny’s Blues, into blueprints we could admire and trace. Projected on a screen or drawn across a whiteboard these stories formed beautifully intricate designs. Stories and characters had arcs, they had inciting incidents that propelled their narratives, backstories that anchored them, denouements and moments of catharsis that brought us closer to some truth. These arcs seemed more apparent as the world around us unraveled and hurtled into something different that year. Were the hollowed-out lockdown streets the start of a narrative or the end of another? Were the semi-crowded ones I saw in the early months of 2020–in a Beirut where garbage bins and tires were dragged onto highways and set alight by tired and anguished protestors, only to abate slowly as the sun came down–inciting incidents or symbolic of a period in which the suffering of a nation seemed to know no end? While in the MFA I wrote often and in varying forms about buildings or structures in decline. Many of these stories took place within them. At the end of 2020, I returned to Beirut a second time to find them surreally materialized before my eyes, in the aftermath of the August 4th port explosion. The devastation was so severe it felt like the stuff of fiction and gave me a sense of something that was greater and more important than anything I had written about.

Someone once told me that what you really learn in workshop is not how to write but how not to write. In the process, you wage war against undefined or weak narrative stakes, melodrama, sentimentality, the eternally unwelcome deus-ex-machina and, of course, cliches. All writers have indulged in or succumbed to these at some point. But the cliche of a workshop or even classroom as a kind of fighting pit seems to hold true when thought of not as a place in which to compete with other writers, but as an environment in which your relationship with yourself as a writer is allowed to play out. More than producing work and getting feedback on it or weighing yourself against the other writers in the room, the workshop is a place in which to come to terms with your own ego and vanity and their expectations. It encourages you to write poorly in the hope of writing well, to make as many mistakes as possible and, ultimately, to write your way back to writing in a way that’s truly you.