Natasha A Fraser takes us aboard the legendary film mogul Sam Spiegel’s yacht Malahne, where Hollywood stars, politicians, and artists mingled in luxury. Reflecting on her memories of working for and knowing Spiegel, Fraser remembers his eccentric life on deck—the place to see and be seen at the Cannes Film Festival.

From the 1960s until the early 1980s, the hot ticket at the Cannes Film Festival was an invitation to Malahne, the boat of film mogul Sam Spiegel (1901–1985).

It lacked a helipad, a swimming pool, and other modern-day features. Spiegel—the only film producer to have won three Best Picture Oscars within eight years and been solely credited for them—did not need such gimmicks. His magnificent 165-foot-long twin-screw motor yacht, built by Camper & Nicholsons in 1937, was enough. As was his setup: Gaston van Hanja, his excellent Corsican chef; his two stewards, Barbadian and Irish but both named James; and the promising parade of his friends who ranged from Greta Garbo to Jack Nicholson to kingpins in the rock ‘n roll business such as Atlantic Records’ Ahmet Ertegun, politicians such as Roy Jenkins, and members of the Jet Set such as Gianni Agnelli.

When the film Easy Rider (1969) became a smash hit at Cannes, Spiegel invited the entire team on board Malahne because he knew the parents of Peter Fonda, Bill Hayward, and Bert Schneider. The party also included Dennis Hopper and Jack Nicholson. “We looked pretty wild in our fringe jackets and long hair,” said Hayward. “On the boat were all the Columbia brass who had pooh-poohed our picture when we had wanted to take it to Cannes.”

Mahlane out at sea. The yacht can still be chartered today.

Spiegel became very English when pronouncing the word boat; not unlike Tony Curtis in Some Like It Hot (1959). Alas, when staying on Malahne in 1980, I was an ungrateful 17-year-old. True, it was fun being introduced to Ahmet and Mica Ertegun, Mick Jagger, and Sophia Loren but I soon became bored by Spiegel’s elegant harem. My cousin and I wanted to slip on our strapless dresses and high heels, hit the Saint-Tropez discothèques, and go “Upside Down”, to quote Diana Ross’s 1980 summertime smash. But dear Sam was possessive. He even got annoyed with flirty Jagger. “Mick, you’re manipulating my English girls,” he complained. And he was furious when Monsieur Jagger quipped, “No, Sam, they’re manipulating me.” Oh, the cheekiness of Jagger and the sincere foolishness of my youth. Malahne’s luxurious circumstances were utterly wasted on me. My cousin and I discovered fruit-flavoured Hollywood chewing gum; our chewing appalled Spiegel. “You look like a cow chewing in a field,” he said. Fortunately, Spiegel was a forgiving chap—it probably helped that my stepfather was Harold Pinter—and he never held such behaviour against me. In fact, Mr Spieeegel, to quote Greta Garbo, or Spiggley Wiggly—Maria St Just’s nickname—became my first boss. I was hired as a lowly gofer on Betrayal (1983), his final film, and I like to think that I paid him back by writing an accurate and well-reviewed biography in 2003. In his glowing review, JG Ballard referred to Spiegel as “the baddest of the Hollywood bad boys” as well as “a genuine mountebank, a congenital liar, and fraudster who produced The African Queen (1951), The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), and Lawrence of Arabia (1962) (“Dunes, baby, I want dunes”). Describing my book as “a fascinating piece of social history,” The Observer’s Philip French wrote, “Spiegel’s first 50 years read like a racy, picaresque novel co-written by Harold Robbins and Saul Bellow. His biographer’s diligent research has discovered far more than anyone knew about his romantically shady past, much of which Spiegel sought to conceal.”

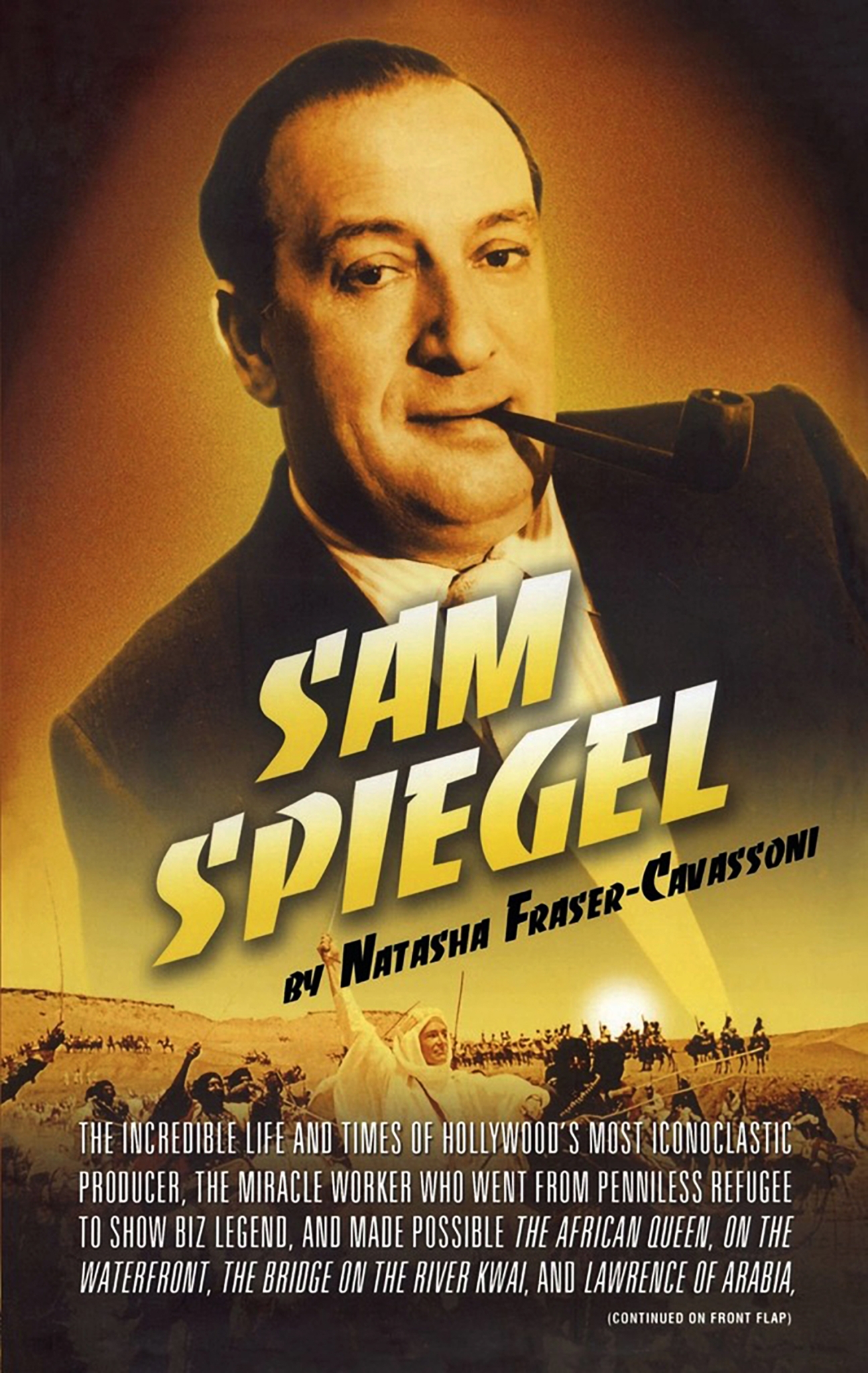

Sam Spiegel – Biography of a Hollywood Legend (2003) by Natasha A Fraser.

Sam might have enjoyed the attention but wouldn’t have approved of my book. I found prison mug shots when he was arrested in San Francisco for bouncing a $10 check in 1927 and all sorts of other goodies. “All I can remember is the guy never paid his bills,” said the son of Sam’s immigration lawyer, who got him pardoned. Nevertheless, Sam Spiegel—The Biography of A Hollywood Legend (2003) captures the life of a maverick who, when living in 1920s Palestine, predicted: “I’ll either become a very rich and famous man or I’ll die like a dog in the gutter.” In the view of John Huston, his co-partner at Horizon Pictures from 1947 to 1953, “Sam Spiegel was the best producer, but he just had two problems: money and women.” Mike Nichols, who attempted to work with Spiegel on two projects, described him as “the very soul of true ideas in a movie—the mystery and the contrast.” Nichols told me: “I think that’s what made him unique, nobody combined those things. Put them all together and he was as close to an artist as a producer could get.” John Box, Lawrence of Arabia’s production designer, didn’t always agree with Spiegel but referred to him as a brilliant producer: “Listen, he kept Lawrence and that wasn’t easy.”

It was due to Lawrence of Arabia that Malahne took centre stage. And it was due to Lawrence that there was a new verb in the film business: “To Spiegel”—meaning to soothe or cajole another. As all David Lean enthusiasts know, the first part of the epic was being filmed in Jordan, an Arab state. The Middle East situation was precarious, particularly for the Jewish-born Spiegel with strong ties to Israel. (His ageing Mutter lived there.) His fear was genuine. According to Sir Anthony Nutting, the film’s official Oriental Councillor, for the first half of the film, Spiegel was petrified of being “poisoned intentionally”, and during the second half “poisoned accidentally”. But true to form, Spiegel turned the liability into an asset. This attitude defined his modus operandi as a producer. He insisted that Malahne be included in Lawrence’s production costs because then he’d avoid sleeping on Arab soil.

This infuriated Lean who compared Malahne’s astronomical expense to “stealing the stuffing from the turkey.” But who was he in partnership with? And who had managed to get Hollywood financing for Lawrence? Before Spiegel, the successful establishment figure Sir Alexander Korda had tried and failed six times with Lawrence, Columbia’s Harry Cohn had even toyed with the idea, while producer Anatole de Grunwald, touting the then matinée idol Dirk Bogarde, had eventually thrown in the towel. Admire Spiegel or despise him, but he succeeded where most other producers failed as illustrated by his films The African Queen and On the Waterfront (1954). “Nothing fazed him,” said Elia Kazan. “When he went to Africa with John Huston, he was this fat Jewish fella who didn’t have a gun… He had a lot of guts.” In Arthur Penn’s opinion, “he had the guts of a blind burglar.” (Penn directed The Chase, produced by Spiegel in 1966.) But he was also, to quote Billy Wilder, “a modern-day Robin Hood who steals from the rich and steals from the poor.”

Original poster of Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954). One of Spiegel’s greatest successes.

Wilder was with Spiegel when he first saw Malahne. While Spiegel was inspecting the cabins designed by Charles E Nicholson, Wilder stayed on deck. Afterwards, he took his friend aside. “I’ve been talking to the crew,” Wilder began. “They tell me it takes nine people to run the boat, and that’s when it’s in the harbour. When it’s at sea, you’ll need a crew of 14 day and night… Nobody can afford a boat this

size anymore, Sam. You must be going crazy.” After looking at him for a moment, Spiegel said, “Don’t be so plebeian, Billy.”

The novelist Gore Vidal—who had just written the Suddenly, Last Summer (1959) screenplay for Spiegel—accompanied Spiegel when he took possession of Malahne in 1960. “The captain, Hector Tourtel, who was like a retired British admiral, said, ‘Mr Spiegel, under what registry do we sail?’ And Sam, knowing that I was standing there, gives me this tricky look. ‘Panama,’ he replied. I then looked at him and said, ‘Sam, tell me, what is the national anthem of Panama?’ Colonel Bogey March came the reply,” citing the music from The Bridge on the River Kwai that led to Spiegel’s second Oscar.

No question, the portly Spiegel had chutzpah and style. Lean’s wife Leila Matkar, who was born in Hyderabad, India, believed he had been a maharajah in a previous life, whereas Geoffrey M Shurlock from the Motion Picture Association of America was reminded of the Roman emperor Vespasian, the founder of the Flavian dynasty.

Faye Dunaway—who disgraced herself when staying on Malahne by making countless long-distance calls to Moscow—sensed that the boat was Spiegel’s true love (an interesting proposition, considering that Sam had been married three times). Although bought from a Belgian industrialist, Malahne’s original owner was William L Stephenson, in charge of the Woolworth’s chain in Britain. A passionate sailor, Stephenson built Malahne as the tender to his racing boat, the J Class Velsheda. Concerning the names of the boats, Stephenson had three daughters: Velma, Sheila and Daphne. Velsheda was the combination of the first letters of their name while Malahne combined the last letters. When Malahne was launched in June 1937, Yachting World magazine called her “a very graceful ship” with “proportions so good that she will never seem dull or unattractive.”

The yacht was in Spiegel’s possession for 23 years. Just as Malahne charted his playboy producer lifestyle, it also briefly charted his relationship with Lean during Lawrence of Arabia, Steven Spielberg’s favourite movie. “(It) did more to inspire me to want to make movies than any other film,” Spielberg said when receiving the BAFTA Fellowship in 1986.

“He had the guts of a blind burglar.” – Arthur Penn, Director

In a sourpuss mood, Lean referred to Spiegel as his nemesis, yet magic happened between the sparring partners who were polar opposites. On the one hand, Lean was content that Spiegel breezed in and created a kingdom in the bay at Aqaba, Jordan. “OLD PORT PERFECT WITH JAMAICAN BLUE SEA PALMS MASKING NEW BUILDING AND ANCHORAGE FOR YACHTING GENTLEMAN” was Lean’s cabled description of the place. Yet the Oscar-winning director managed to be dismissive about Malahne. His chief complaint being that when “putting one’s head to the pillow, the hum of the generator bore into one’s ear like a dentist drill”.

Nevertheless, there was a camaraderie between the two. Enough for Spiegel to feel comfortable insisting that Lean share his bedroom suite on Malahne, when he was scared of being in Jordan. Before turning off the lights, the director opened the French windows, looking onto the bay. Spiegel, who was then in bed, asked where Israel was. Lean wasn’t sure but pointed his hand into the dead of night. “Don’t point, they’ll shoot,” the producer cried out.

Naturally, there were strict rules when dealing with the King of Jordan. “If you want to talk about politics or religion, I’m not taking you,” Spiegel warned his film stars, such as Peter O’Toole, when they were invited to the palace. Lined up on the deck of Malahne, they promised to avoid both subjects. However, during dinner, Spiegel heard one of his team asking countless questions about Ramadan. There was a silence until the Jewish-born Spiegel boomed, “You know what it’s like. It’s exactly like our Lent.” Phyllis Dalton, Lawrence’s costume designer— and one of the rare women on set—recalled Spiegel’s parties on Malahne. “When he’d had enough, he’d stand on the gangplank with a watch in his hand,” she said. “Sam was an absolute monster, but he had an awful lot of charm.”

Lean’s lasting bone of contention against Spiegel was leaving the spectacular Wadi Rum, renowned for its towering red cliffs rising 2,000 or 3,000 feet from the pink sandy floor of the Jordanian desert. “The thing that’s going to make this a very exceptional picture in the world-beater class are the backgrounds, the camels, the horses, and the uniqueness of the strange atmosphere we are putting around our intimate story,” Lean wrote to Spiegel. Still, in Dalton’s opinion, the departure was necessary, otherwise Lean “would have died there.” Nutting was of the same conclusion, viewing Lean as “yet another Englishman going potty in the desert”. Most importantly, Box advised the move. “There was no way we could have built Cairo or Damascus out there,” he told Kevin Brownlow, Lean’s biographer.

After Spiegel’s letter stating the first unit shooting had to be finished in Almeria by the end of June, Box was sent to Monte Carlo with a vitriolic and terrifying letter from Lean. Slight problem, Spiegel was in no mood to be hassled. “Sit Johnnie, relax… sleep on Malahne tonight and I’ll give you an answer tomorrow,” he said. The next morning, Box woke up to find that he was in the middle of the Mediterranean. “Sam was up there with all these girls swimming around the yacht,” he said. But Lean’s letter was left unopened. Two days slipped by, Spiegel still refused to read it. However, on the third morning, the letter had disappeared. Box pressed him for an answer. “That’s easy, tell him to fuck himself,” Spiegel replied.

Contrary to Lean’s complaints, Spiegel always had Lawrence’s screenplay at hand. This was proved when it was too windy to shoot in Almeria because the voices couldn’t be heard. When reached on Malahne, Spiegel said, “How about the insert of the pistol?” because the wind couldn’t affect that. When it came to editing, the battles continued. Columbia’s Leo Jaffe was flown in to help resolve the ending, but the film executive refused. “I don’t deserve to,” reasoned Jaffe. “You fellas have got to work it out.” And they did, leading to seven Oscars in 1963. Offering an olive branch, Spiegel invited Lean to dinner at The Berkeley, one of the director’s favourite restaurants. Lean decided to let him have it, citing Spiegel’s cables, messages, and general behaviour. “Why did you behave so badly to me?” he asked. “Baby, artists work better under pressure,” came Spiegel’s reply.

After his third Academy Award, Spiegel was treated with sincere respect in the film community. But the success dulled his instincts. “People get corrupted,” Barry Diller told me. “They don’t lose their brains. God knows, they don’t lose their talent. But part of the process of success and what it does, it removes their objectivity, it removes their instinct.” In David Geffen’s opinion, “Sam should have stopped making films after Lawrence.” Impossible, Sam Spiegel needed to keep relevant. And being a producer was essential for his love life. “To young actresses, he held up the ultimate carrot— maybe a part in his next movie,” said Carrie Haddad, Spiegel’s tawny-skinned and nubile girlfriend during the 1970s.

Once the first part of filming finished, the Spiegel-Lean relationship seriously nose-dived. Nina Blowitz, the wife of Spiegel’s PR William F Blowitz, recalled a dinner on Malahne in Spain where she was seated between the two. “We had started out with caviar and blinis, and Sam says, ‘Ask David if the wine is all right.’ Then David replies, ‘Tell him it’s all right.’” This continued all night. “They were like kids,” she told me.

Major pressure emanated from Columbia Studios to finish Lawrence, particularly due to Cleopatra (1963), a disaster of epic proportions, and Spiegel insisted that Lean used second unit directors. It was everything that Lean passionately loathed but his hand was forced. Nor did Spiegel help the situation by his manipulative pièce de resistance: feigning heart attacks. Grabbing his chest, it became quite an act. “You’re giving me a heart attack,” he’d say. Adding dramatic effect, he was even prepared to fall to the ground on occasion. I’m not being callous. His British doctor advised calorie control but never mentioned a heart condition.

“Spiegel was the best producer, but he just had two problems: money and women.” – John Huston

Malahne became a never-ending Spiegel production. “Warren Beatty called Sam the ‘unit manager’ because he was always making arrangements,” said George Stevens Jr, AFI’s founder and namesake son of the director of Giant (1956). Just as Spiegel’s Hollywood New Year’s Eve parties between 1944 and 1953 were not to be missed, neither was an invitation on board Malahne, where stars rubbed shoulders with politicians, aristocracy, and the super-rich; not as obvious as it sounds. “There was such comfort,” said Stevens. “The bathtubs were perfect, and just as the sun was setting, James (Jordan) would bring you a martini.” I still recall how the soft-footed Barbadian steward filled glasses soundlessly.

Malahne’s deck was teak, while the dining room, on the lower deck, was lined in walnut. Before and after a drawn-out lunch, guests either soaked up the rays on the upper deck or stayed in the Blue Saloon—the lounge area—where newspapers were delivered, gin rummy games were played, and screenplays were conducted. Since Spiegel could become authoritarian, Wilder nicknamed him Captain Bligh (after the famous case of the mutiny on the Bounty). They were amused by the modest wording of the Blue Saloon’s plaque, which read: “Oh God, thy sea is so big, and my ship is so small.”

Although Malahne had appeared on the cover of Life magazine under the heading “Luxury and Languor of Riviera Yachting”, the experience wasn’t for everyone. When veteran director George Stevens Snr was briefly working on the film Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) and Spiegel proposed scouting locations from his boat, the veteran director said, “Sam, have you heard of the Learjet?”

In total, there were five cabins for Spiegel’s guests but, because they varied in size, there was a mad rush for the first two suites, which had double beds and adjoining bathrooms. “People used to change their flight times to make sure they arrived before anyone else, since it was always first-come, first-served,” said Spiegel’s interior decorator Tessa Kennedy. “And Sam used to get so angry about it.”

Since the guests on Malahne were multi-generational and multi-cultural, there were strange occurrences. When introduced to Brigitte Bardot, British prime minister Edward Heath had little idea who BB was. Nor did one Italian aristocrat recognise his lunch partner Greta Garbo. And when Spiegel was called away and returned to announce the atrocious Manson murders, not everyone had heard of Sharon Tate. Sometimes, Spiegel was the peacekeeper. When the charismatic conductor Herbert von Karajan arrived for supper on Malahne—his enemies nicknamed him SS Colonel von Karajan due to working during the Nazi era—Spiegel had to reason with his guest Isaac Stern, the staunchly Jewish-born violinist. Spiegel also disapproved of Nicholson dropping his trousers and mooning to his female fans waiting at each port’s harbour. “He scolded him like a son,” said the photographer Willy Rizzo. And when Geffen, then a record producer, told Irene Mayer Selznick to fuck herself, Spiegel intervened. “Darling boy, she drives everyone crazy but you must apologise. You’re on my boat and you must apologise.” Selznick, on the other hand, insisted that she had done her “best not to be Mrs Danvers” and all had worked out well, “despite David’s distinct lack of charm.”

Sam Spiegel photographed with David Lean (1960).

By the late 1970s, Malahne started to show the wear and tear of the cruises. Equivalent to a prized but wobbly vintage car, every time the boat was used, something went wrong. “Sam would fly down for the weekend and the captain would pick him up and say the tender wasn’t right or the launch wasn’t working,” said Alan Silcocks, his English business manager. When James Jordan retired in 1983, Spiegel said, “That’s it”, and sold Malahne to Sheikh Adel Al Mojil. But was his Barbadian steward really the cause? Or did one Hollywood director’s wife sum it up best? “Poor Sam, he has this expensive boat and half his life is spent searching for guests,” she said. The yacht remained glamorous, the topless sunbathing continued, but the casting had slipped a notch. “Sam got involved with the Eurotrash, which was very boring because they only seem to find themselves interesting,” opined decorator Joan Axelrod.

Hence forward, summers with his teenage son Adam Spiegel (born in 1968), later to become the very successful theatre entrepeneur, were spent at Mas d’Horizon, Spiegel’s villa near Saint-Raphaël. Spiegel’s deafness was the only sign of his age. “Sam, I think you should get a hearing aid,” Ertegun would say; advice that was stubbornly disregarded. In early December 1985, the producer had a prostate operation in London. Ignoring his doctor’s advice, he then travelled 6,000 miles to New York and made a new will on Christmas Eve. A few days later, Spiegel left for Saint Martin in the French West Indies and stayed at La Samanna hotel. Like Malahne, it was named after the owner’s three daughters. And on New Year’s Eve, Spiegel was found dead, looking blue in the bathtub. Joseph Mankiewicz recognized the irony of Spiegel dying “on the night that he was famous for, long before he was known as an excellent producer.” But it’s difficult not to agree with Geffen that it was exactly the right way.

“Sam had a great life, it wasn’t as if he ever cut down on his cream.”