One of the great British novelists, Graham Greene found solace on the Italian island of Capri where he purchased a house named Il Rosaio. It remained a sanctuary of productivity and inspiration toward the end of his life.

Grahmgrin is how they said his name on the island—that quick Caprese tongue squishing the writer’s name into two flat syllables, as if eager to get it out into the world and get on with lunch. Capri has always rather liked writers, in the same way that a brusque matron rather likes her rascally schoolboys: welcoming but never doting; unfussy and yet hospitable. Pablo Neruda, the Chilean poet, stayed here for many years in exile from his totalitarian homeland, and various scattered verses of his are still set in worn stone high up on the rugged walkways. Somerset Maugham summered here often. Norman Douglas barely moved from the bar at the top of the funicular for several decades. His novel, South Wind (1917), is as rich a flavour of the island as the bright yellow local wine that he consumed there by the litre. By 1907, Rilke was already a sufficient part of the furniture to decry the “hideous impositions” of a few modest hotels. (What might he make of the idling yachts?) I once spent a late morning in the small hillside house of the island’s oldest Latin teacher, whose blinds were shut tight against the gorgeous sunshine so as not to fade the many musty books that lined his family study. The view over the hills and coves was spectacular—but not nearly as fascinating, to Il Professore, as the chair where once a minor German novelist had sat on a half-forgotten evening.

Most of these authors were drawn to Capri by the rugged exile and romantic isolation, if not the warm weather (though this was a false friend: in winter, Capri is famously wind-savaged, while the top of the monolithic Monte Solaro seems to wear the dark rain clouds like a bad mood). The aesthetics also helped: vast blue skies and star-filled nights; jungled greenery slung on perilous rock faces above crystalline waters. But Greene was mostly unmoved by natural beauty and had no great appreciation for the visual. His novels—The End of the Affair (1951); The Quiet American (1955); The Power and the Glory (1940)—are more interested in moral ambiguity and human frailty than purple descriptions or sublime vistas. Which makes his long posting on Capri one of the many strange contradictions and riddles in a life full of them. As Greene wrote of a character in his first novel, The Man Within (1929): “He was, he knew, embarrassingly made up of two persons.”

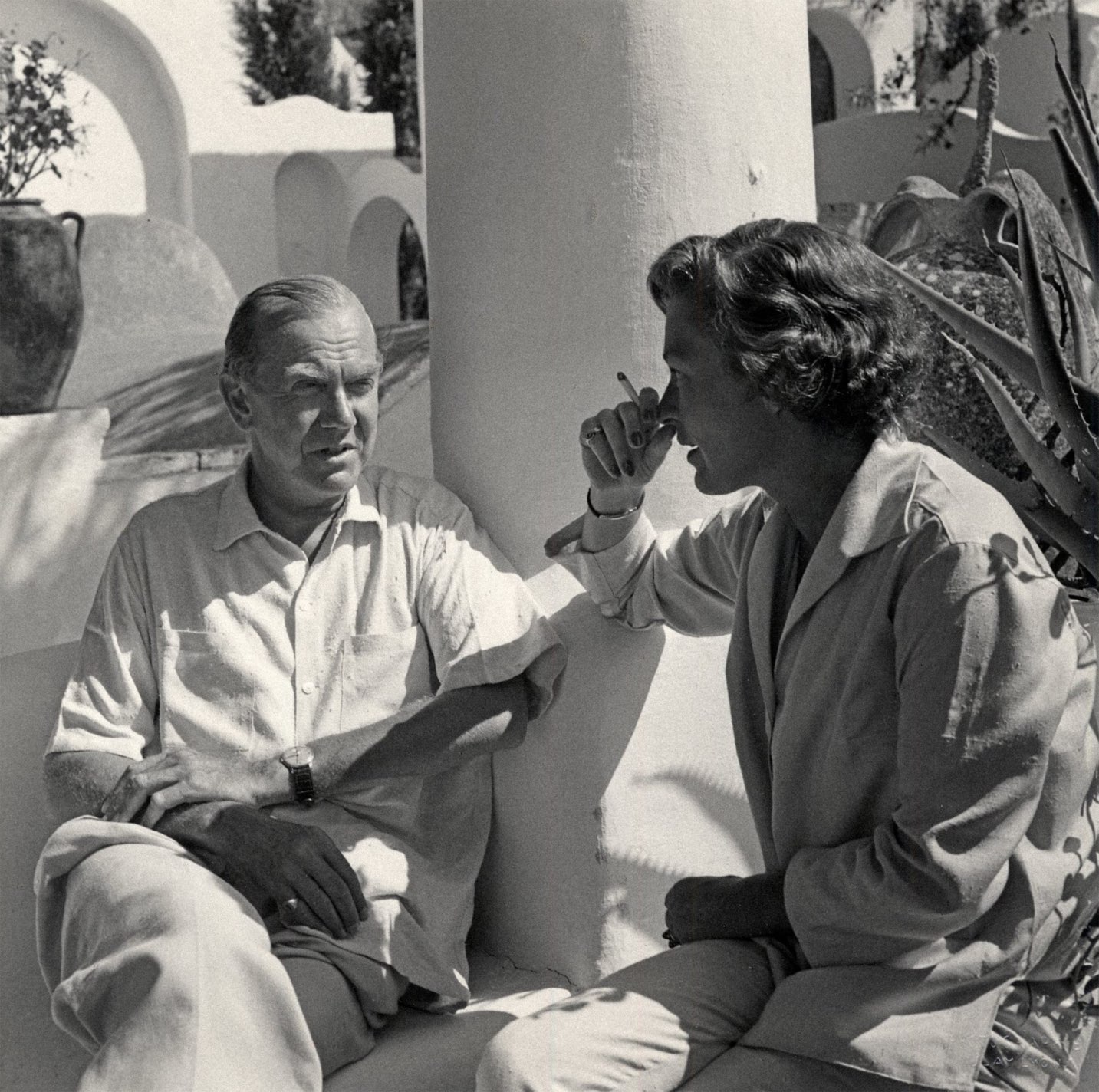

Shirley Hazzard’s book Greene on Capri (2000).

The answer to Greene’s puzzling affair with Capri lies in the small house called Il Rosaio. It sits on the corner of an anonymous thin road set a hot stroll away from the squares of Anacapri, the less touristy sister to the main village. I stood outside it on a recent trip and touched the warm walls for want of anything else to do. Washing flapped overhead and a cat hissed near hot rubbish.

Joseph Bullmore

The answer to Greene’s puzzling affair with Capri lies in the small house called Il Rosaio. It sits on the corner of an anonymous thin road set a hot stroll away from the squares of Anacapri, the less touristy sister to the main village. I stood outside it on a recent trip and touched the warm walls for want of anything else to do. Washing flapped overhead and a cat hissed near hot rubbish.

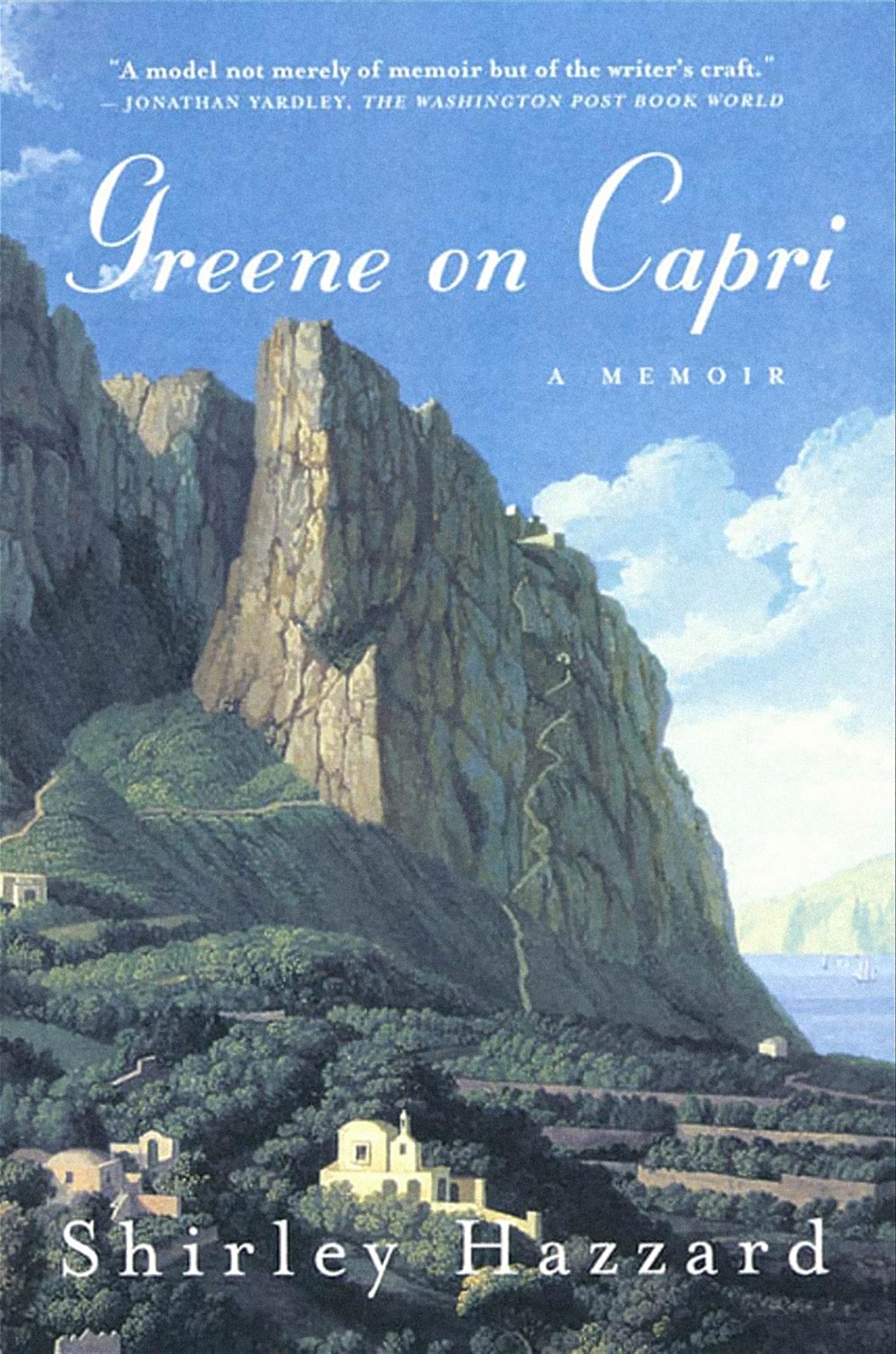

Greene bought the house in 1948 and lived there, in fits and starts, for four decades. The acquisition was fiscally motivated as much as anything else. Greene had made some decent money writing the screenplay for The Third Man (1949), and a chunk of his European royalties were apparently stuck in Italy. Rather than getting them out at great expense and effort, he plonked the cash into the little white-washed cottage in Capri, which, he rather proudly proclaimed, came complete with its own pots and pans. After his death, a grand plaque was erected on the exterior of Il Rosaio to commemorate the author’s time there. His neighbours, knowing that this would have seemed ghastly to Greene, promptly took it down.

A plaque dedicated to Greene from 1992.

“In four weeks [on Capri] I do the work of six months elsewhere… I have no talent. It’s just a question of working, of being willing to put in the time” — Graham Greene

Inside Il Rosaio’s walled garden—a mazy, blossoming patch, which seemed somehow more Moroccan than European—a small structure stood at the upper end: Greene’s cabin-like studio, with plain white walls and narrow bookshelves. Shirley Hazzard, whose excellent book Greene on Capri (2001) illuminates the writer’s life and moods there, remembers how “there was a small divan chair, a lightweight portable type-writer on a solid old table by a window that looked out on the garden”. It was, she says, “a fine place to write: indrawn, inviolable—a refuge within the retreat, and all within an island”.

It was at that solid table that Greene tapped out his unfailing minimum of 350 words per day—his “daily penance”, as he once told a friend. The words came easier, faster, thicker in the grip of Capri’s damp, salty heat. “In four weeks [on Capri] I do the work of six months elsewhere,” he said, stressing to the last that, “I have no talent. It’s just a question of working, of being willing to put in the time”.

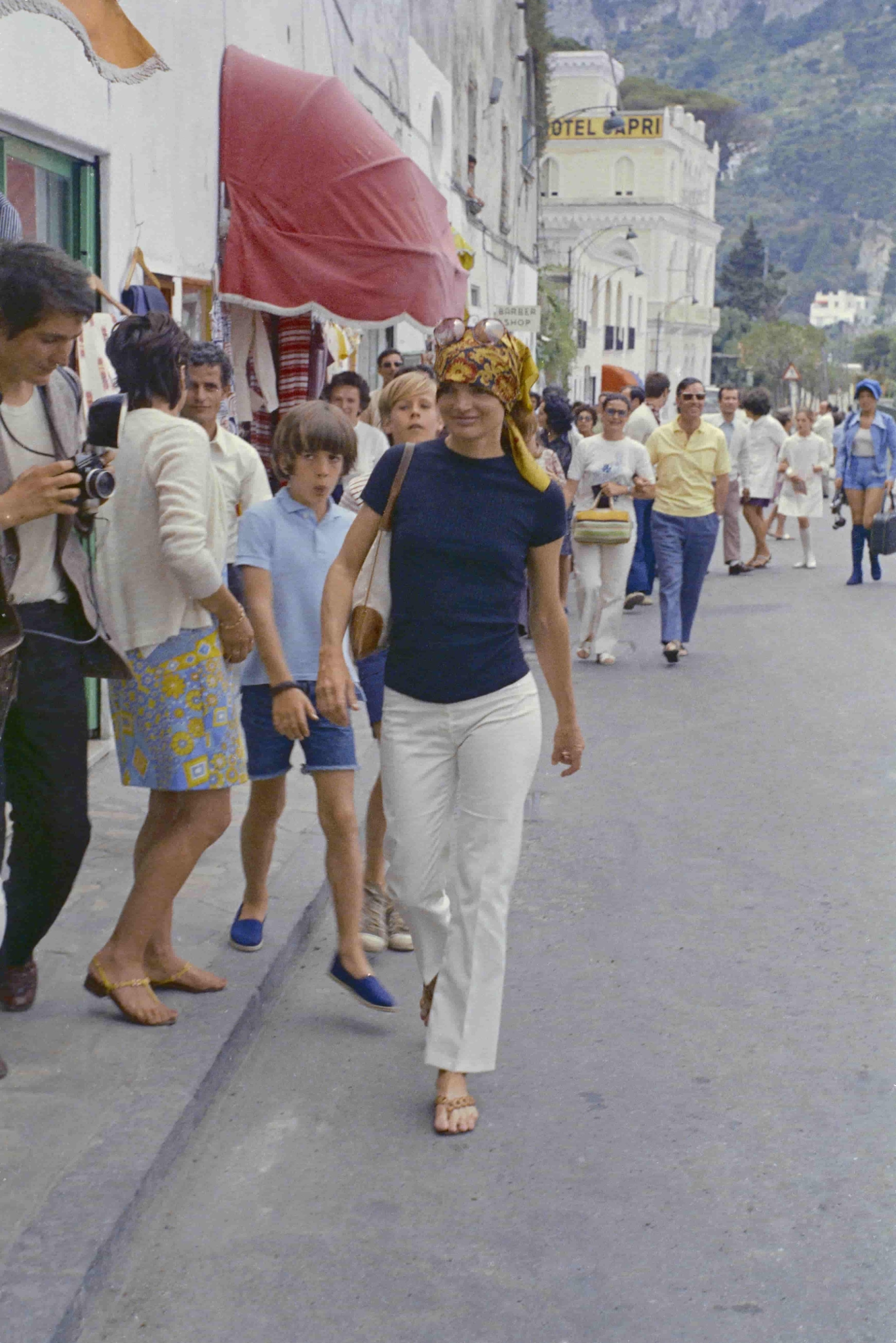

Capri, it seemed, allowed Greene that time—untethered from the rush or temptations of Paris, where he had a flat, or the swoony cafe culture of Antibes, where he was otherwise based. Capri was a quiet place of reliable food, strong coffee, and wet wool in the autumn afternoons. The island in the 1950s had not yet installed its Rolex boutiques or seen Jackie Kennedy’s cropped pants; had not yet welcomed the ferried, bewildered Americans in turquoise golf tops that seem a ghastly distortion of the local waters, arriving in the Marina Grande in a fug of diesel and sun lotion to be shuttled by topless taxis into the familiar embrace of lemon fridge magnets and creamed carbonaras. Nor had it yet been appropriated by the hordes of cosplaying influencers who come allegedly for the dolce far niente but end up doing really quite a lot—posing, again and again, with performative vongole in the beach clubs while boyfriends in rose-gold Nautiluses crouch and sweat, terrified lest a bad camera angle be some indication of a bad character. No—Capri was a place of constancy and reliability for Greene, not flash and panache. He did not turn to it for its flavour but for its blandness. Not caviar but plain cracker. He never once wrote about the island in any of his books. And yet it allowed him to write about everything else. “My connection with Capri is odd,” Greene once told a friend who lived there. “It is not really my kind of place.”

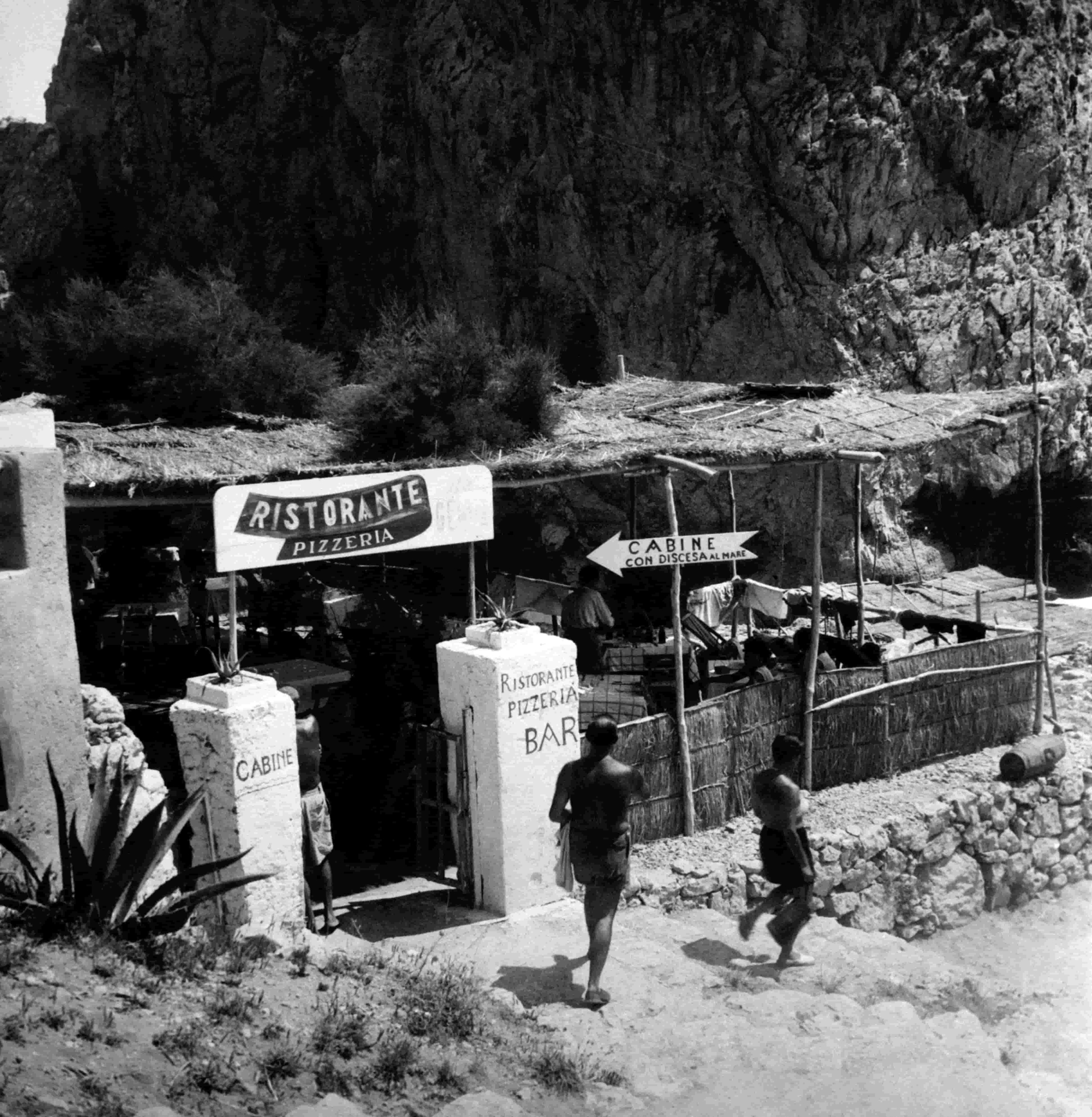

Parts of it were, though. Greene was particularly fond of a scattering of restaurants on the island, particularly Da Gemma, which opened in the 1930s and which still hugs a cliffside bend just outside of the Marina Grande. “The unadulterated simplicity of Gemma’s restaurant was a stable factor that helped make the island agreeable to Graham,” Hazzard writes. “Like many restless people, he preferred to find his ports of call unchanged.” After an early dinner—an unfashionable quirk that was typical of Greene—he would stroll up to the Gran Caffé in the main piazza for grappa and coffee, before catching the slow bus back to the cloudy heights of Anacapri. (Greene, though by that time independently wealthy from his many writing projects, made a point of a certain perverse frugality.) The spaghetti al nerano is still very good at Da Gemma—a gooey antidote to the sharp local white.

Greene was cool against the island’s easy affections. He was bestowed with an honorary citizenship in the late 1970s, and fussed and scowled for weeks before finally accepting the accolade during a hushed, solemn service in the church at San Michele in front of an audience. In the 1970s, Green was offered the Malaparte Prize—a Capri literary gong accepted by plenty of well-known authors—but declined it on grounds of taste and politics. For one thing, Curzio Malaparte, the prize’s name-sake, was a vicious fascist during the island’s war years. And he had also built a low-slung modernist mansion—later immortalised in Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris (Contempt, 1963)—on the island’s south-eastern coast: a terracotta war-bunker of a thing, signed off against the unblemished beauty of that coastline by Mussolini himself. Perhaps, in his own roundabout way, Greene’s snubbing of the prize was a nod of defiant affection for the island at last.

On one of Hazzard’s final encounters with Greene, on the island or elsewhere, she remembers how Greene recalled the words of Henry James, written in the early 20th century after James had first set eyes on Capri himself. It was, he wrote, “beautiful, horrible, and haunted”. The point was made that perhaps James was using the archaic form of the word horrible: of inspiring great awe. Greene wasn’t so sure. But it is clear that the island—long haunted by waifs and geniuses, monsters and escapees—had inspired something great in him: a mid-to-late period of huge productivity and acclaim, if such things matter. It is amusing now to imagine his ghost among the content creators.

Foot Note

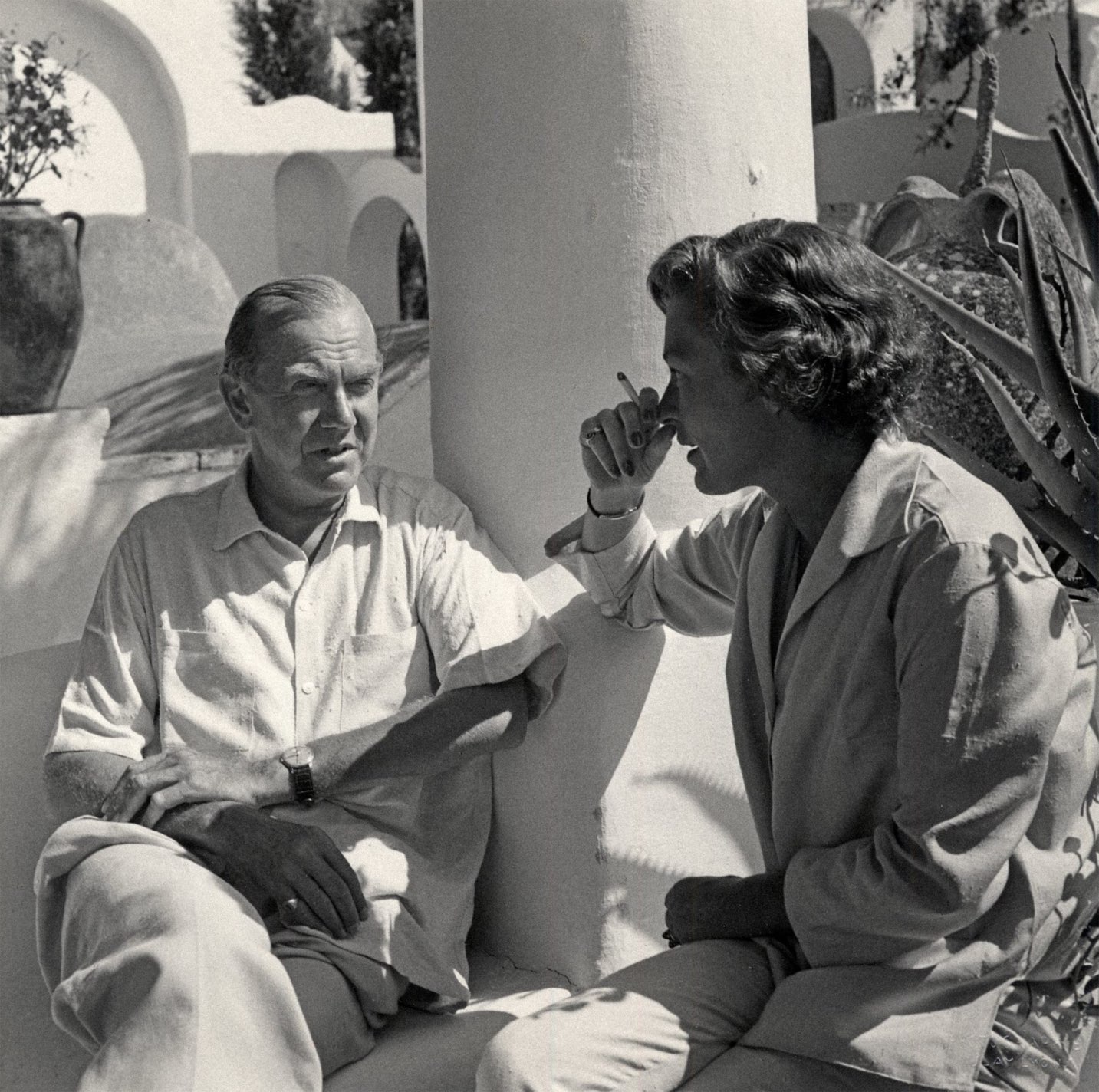

Graham Greene was associated with cinema during his time, most notably with the great Austrian-American director Otto Preminger (Bonjour Tristesse, 1958). They worked together on the 1953 film The Moon is Blue, and later—and more significantly—on Preminger’s masterwork The Cardinal (1963), the story of a Boston priest who deals with love and racism as he rises through the ranks of the church. Their collaboration hit its zenith much later, when Preminger adapted The Human Factor (1979), a Cold War espionage story. It was one of the few film adaptations Greene enjoyed. Typically for Greene, his relationship with Preminger, as prolific as it was for a writer-director, remained more professional than anything resembling a friendship.