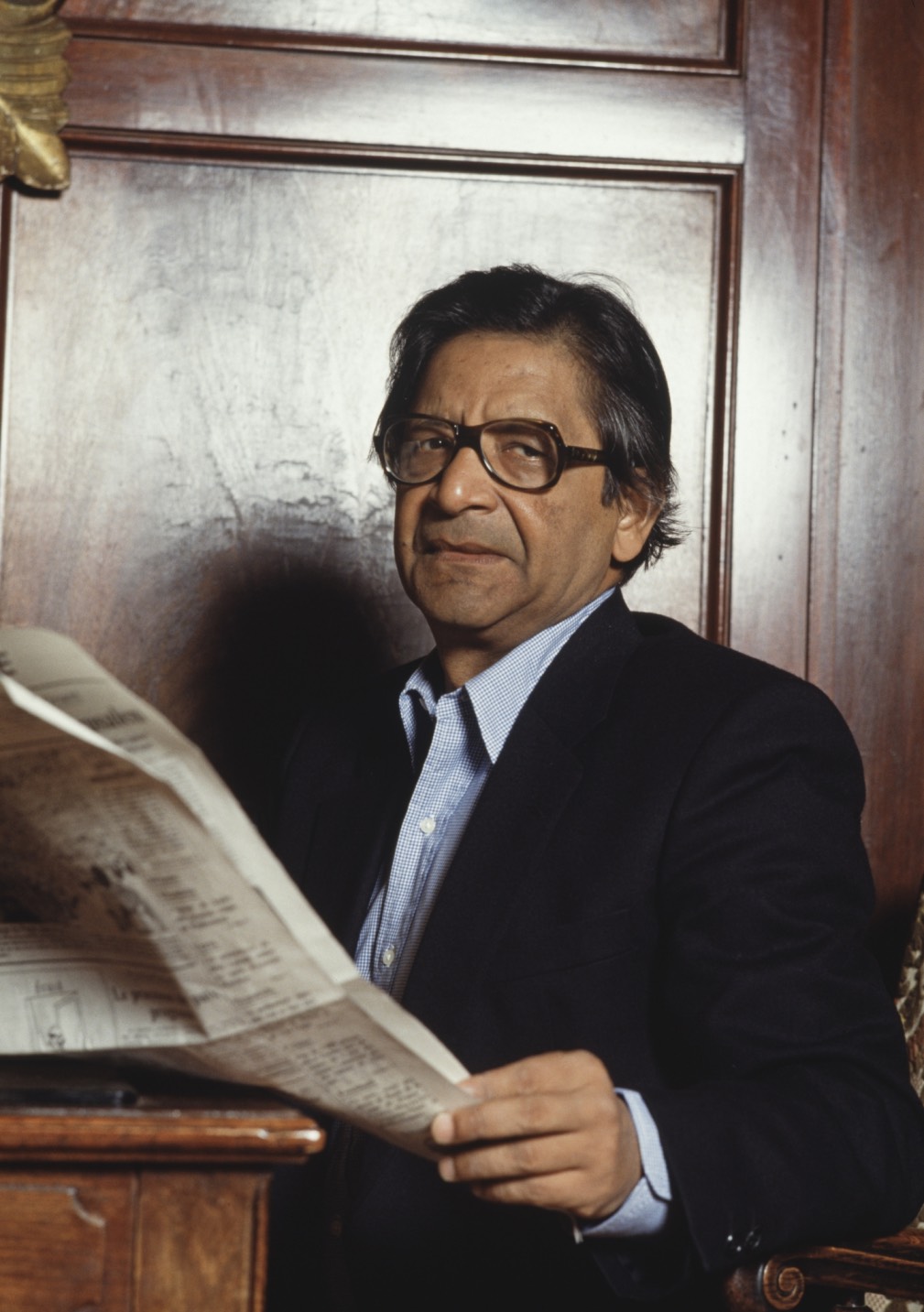

Few people got to know the great author VS Naipaul like the writer Aatish Taseer did. Here, he recounts one of his fondest memories with Naipaul, one of his mentors, on a museum trip in Delhi.

“Leave it—leave it in the car,” Lady Naipaul said. Nadira was afraid VS Naipaul’s olive-green felt hat would make the writer appear too English. That would mean us paying the foreigner’s entry fee at the National Museum, which was 30 times the Indian fee. It was not the money; there was something insulting and arbitrary, yet revealing, in the way it was decided at the door who was Indian, who was not. I had only recently moved back to Delhi, where I grew up, and I was especially sensitive to questions of authenticity. I had sent my driver ahead to buy the ’Indian tickets’, but when we approached the door the security guard wanted to know why we had not bought the foreigners’ tickets. “Because we’re Indians,” I answered in Hindi.

“Show me your passport, or ration card,” the man said.

We weren’t carrying any identification, but neither were a group of young men in polyester shirts and baggy trousers.

“Why aren’t you asking them for identification?” I said.

“Because they look like Indians,” the security guard replied.

“And don’t we look like Indians?” Nadira intervened in fluent Punjabi, which was spoken on both sides of the Indian and Pakistani border.

The man was stumped; it was just a feeling, a class feeling, but the use of Punjabi spoke of an authenticity he could not deny.

“We’re speaking in Punjabi, aren’t we?” Nadira pressed him. “Would we be speaking it if we weren’t Indians?”

The man smiled. “Some foreigners have learned as well,” he said, shaking his head. “But never mind, carry on.”

Naipaul, who now took my hand in his, watched the scene intently but said nothing. I could not help but wonder what the Nobel laureate who described himself as “a double exile”—referring first to his Indian family being sent to Trinidad as indentured labour under British rule, then his leaving Trinidad in search of “the centre” in Britain in the 1950s—made of these strenuous assertions of belonging.

I first met Naipaul when I was 18, on my way to college in America, and he told me not to go: “Indians, they go to these places; they get dazzled by the institution; and they come away having learned nothing but the babble.” We met again a few more times over the years, by chance at the Maurya Sheraton in Delhi where he was teaching the bartender to make a proper martini, and in London at Antonia Fraser’s book launch, where he sat on his shooting stick, looking older and frailer, but still full of mental acuity and humour. When I said that I had just returned from an eight-month journey in the Islamic world—I was travelling for my first book, Stranger to History (2009)—he said, “Yes, yes, yes. They have only one book.”

Naipaul had lived all his life in Britain, where he came on a scholarship to the University of Oxford as an 18-year-old. In 2001, in the shadow of the 9/11 attacks, Naipaul, who had written about the nihilism that lay behind the rise of Islamic fanaticism, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

A few nights before the museum, my mother (an old friend of Nadira’s) gave a dinner for the Naipauls at her flat in Delhi. They were in the city to record a BBC film about Naipaul’s life and for Naipaul to get cataract surgery because he was convinced that the NHS’s doctors were trying to kill him. Once the crew had left—and Naipaul had had his cataracts out—I received a call from Nadira, asking if I would like to accompany Naipaul to the National Museum to see the Chola Bronzes. The Cholas were a seafaring Southern Indian dynasty, who ruled from the latter half of the 9th century until the beginning of the 13th, and whose cultural influence had permeated South East Asia. I had not been to the museum since I was a child, but, in the time that had elapsed since our first meeting (in 1999) and now (2007), I had read almost everything Naipaul had written, and agreed at once. We met at his hotel, the Maurya Sheraton, where he appeared down a marble hallway—a short man with a leonine face, helped along by his wife and a hotel attendant. He had recently had back trouble and moved with a determined but shuffling gait. He was dressed in a light grey coat, a red Lacoste shirt, and an olive-green hat; an Air India baggage tag hung from his shooting stick. We had met only recently, but every meeting with Naipaul was like the first. His excessive formality and a faraway look in his eyes, which have an Asian cast—Naipaul derived from Nepal, because his people came from a town called Gorakhpur, near the Indo-Nepal border—can set what is directly in front of them at a distance, as if in anticipation of a fresh appraisal. I was now subjected to this aloof scrutiny.

He is curious about incuriosity, especially the programmatic kind, because it gives him an insight into how the world is configured. Not just the make-up of an individual, but what a group chooses to neglect, or turn its attention to.

Aatish Taseer

“Yes, yes, yes,” the writer muttered under his breath, nodding his head vigorously in all directions, then, as if as an afterthought, he asked me what I knew about the Chola Bronzes.

“Nothing.”

“Nothing?” he said, the narrow slits of his eyes widening in frank amazement.

“Nothing.”

“Oh, oh, oh,” he said, the triune of exclamations taking a trip of three steps from surprise to disappointment to what felt like a mixture of alarm and pain. I felt he was making a judgment about what my kind of person in India (English-speaking, educated abroad, the “green-card folk,” as he would later say) did or did not know. To be a provincial in Naipaul’s view is not to be ignorant about this or that thing—the world is wide and various, and no one can know everything—it is rather to be so secure in what one does know that you are never forced to examine the nature and causes of what you don’t know. He is curious about incuriosity, especially the programmatic kind, because it gives him an insight into how the world is configured. Not just the make-up of an individual, but what a group chooses to neglect, or turn its attention to. Exile is his fate, but it is also an opportunity, a privilege. It allows him to “look” in ways that others more complacent in their rootedness can never hope to do. He is a student of how power shapes the world and one of the many things he abhors is the systematic incuriosity of those who are so safe in the world, that they render invisible what they ought to see. “And it seemed, in a strange way,” he would write in a book of essays that appeared the following year, “that at the end, when the dust settled, the people who wrote as though they were at the centre of things might be revealed as the provincials.”

The bronzes were a test. They were objects of beauty. Their fame had spread through the Western world. They had been collected in Europe and America for over a century; they sold for a million dollars apiece every time they appeared at auction, which they rarely did. Here was one of the finest collections housed in a museum down the road from me. Why had I never been to see it as an adult? What had prejudiced me against the art of my own country? Did I know what misplaced feeling of safety lay behind my incuriosity?

It was a clear October day. The architectural trees of north India—the towering arjuna, the medicinal neem, the dwarfish jamun—lined the boulevards of British Delhi, their canopies flaring and fading overhead. We came to the edge of a great esplanade, on which there were reflecting pools with pedal boats and bright ice cream trucks. A runway-sized road led up to Edwin Lutyens’ presidential palace, with its many shades of red and cream sandstone, the hovering mass of its copper dome. The National Museum was built in its image, a sandstone bauble impoverished by imitation. We drove in past large metal gates. A grassy oval out front was fed by untreated sewage water and the air stank.

“We’ll look only at the bronzes,” Naipaul said, as we made our way past the security check, “otherwise we’ll get tired.” But once we were inside the musty foyer of the museum, with its bureaucratic stench of stale paper and urine, Naipaul was drawn, as if by a magnetic force, to an 11th-century stone sculpture of a pair of lovers. Wheezing as he caught his breath, he said, “Why don’t you sit down? You’ll be able to consider it better that way.”

I did, but immediately found myself unable to enter the aesthetic world of the statue. It felt too stylised, too mannered. Looking up at the smiling woman leaning into her lover, gentle rolls of fat on her waist, my eye fastened on externals such as the spotlight with its exposed wires, the wooden pedestal of rough manufacture on which the statue stood. It was a particular feature of growing up colonial in India that while traditional means of assessing Indian art had fallen away, nothing had come in its place. The statuary was familiar to the point of cliché to me, but I could not have said why a statue of this kind might be deemed beautiful. I had no vocabulary, no points of reference.

Naipaul started us off with a little background. “This piece,” he said, “is from Khajuraho,” which is in central India, and where I had been. Then he began to do what was almost a pedagogical feature of his writing; he began to simplify, and to personalise. “I have a special feeling for the Chandela dynasty,” he said. “I am named for one of its kings. The invaders were coming. They had to move away. The bush grew over and that was what saved the Khajuraho temples. I fear that they are admired now for their erotic content, which is foolish.”

For someone like myself, who had grown up learning Indian history by rote, a roll call of dates and dynasties, this personalisation of the Indian past surprised me. It felt like ownership. “What is nice,” Naipaul continued, “is the absolute confidence in these faces. These figures are…”

“Complete,” Nadira finished the sentence for him.

To be whole, to be complete. These were words I had first encountered in Naipaul and though they spoke to me, in personal and historical ways—I was half-Indian, half-Pakistani, with an absent father—they also contained hidden dangers. “It was the imaginary wholeness of civilizations,” wrote Ian Buruma, after Naipaul’s death in 2018, “that sometimes led him astray. He became too sympathetic to the Hindu nationalism that is now poisoning India’s politics, as if a whole Hindu civilization were on the rise after centuries of alien Muslim or Western despoliation.” In that moment, Naipaul’s use of wholeness did not feel political. What I was intrigued by was his way of imbuing the dead Indian past with feeling. That feeling may have been one of pain and loss, but, in Naipaul’s hands, it was not yet converted into a politics of revenge. His young man’s belief from An Area of Darkness (1964) that the past must be seen to be dead, or the past would kill, remained intact.

“We won’t look at everything,” he said, as we made our way further into the museum. “Or we’ll get tired. Only at the fine things.”

Walking through a corridor lined with long pieces of carved stone, Naipaul, pointing with his shooting stick, said, “Lintels. We didn’t have the arch; we had lintels.”

“We?” I thought to myself, wondering what deeper soil of belonging Naipaul and I, both historical exiles in our own ways, could be said to spring from.

We passed a red-lettered sign for the bronzes and entered a room of spotlight and shadow, with grubby pistachio-green walls. On the way in, I asked Naipaul about the building the bronzes were housed in. He must have misunderstood my question, for he said, with sudden vehemence, “I’ll tell you, I’ll tell you. These bronzes used to be in the viceroy’s house. They were collected by the Archaeological Survey of India, a British institution. Safe to say, that not a single Indian prince made a collection like the one we see displayed here, though he easily could have. The Maharaja of Patiala went to England where he had his portrait painted—that was the thing to do!— and he picked up a few nudes and brought them back. They gloried in their ignorance.” Naipaul repeated: “gloried in their ignorance.”

Naipaul loathed imitation with a Fanonian ferocity. He was suspicious of cultural encounters and syncretism, unless the meeting was profound, such as that of Bengal and Britain in the 19th century, or when the classical world fertilised Islam. Above all, he admired cultures that were whole; that instinctively knew what was theirs. “Although both England and the United States were each in their own way to fall short of his ideal society,” wrote Diana Athill, Naipaul’s long-time editor, “Europe as a whole came more close, more often, to offering a life in which he could feel comfortable. I remember driving, years ago, through a vine-growing region of France and coming upon a delightful example of an ancient expertise taking pleasure in itself: a particularly well-cultivated vineyard which had a pillar rose, a deep-pink pillar rose, planted as an exquisite punctuation at the end of every row. Instantly—although it had been weeks since I had seen or thought of him—he popped into my head: ’How Vidia would like that!!’”

The famous Nataraja (Chola) bronze, Delhi.

“The purpose of sacred images in Indian art,” writes the Swiss scholar Alice Boner, “is not aesthetic enjoyment. They are focusing points for the spirit. Born in meditation and inner realisation, they should, and this is their ultimate intent, lead back to meditation and to the comprehension of that transcendent reality from which they were born. If they are beautiful, it is because they are true.”

Aatish Taseer

In speaking of the princes, I felt he was establishing antecedents for the colonial class in India to which I belonged and, in his anger about glorying in one’s ignorance, I felt there was a message of caution for me. And yet, even if he was right, even if my colonial education in India had left me out of sympathy with the art I now saw around me, I could hardly overcome that acculturation in an hour. Standing in the room that housed the bronzes, their long limbs casting entrancing shadows over the walls of elegiac green, Naipaul made his way over to the most famous piece—the Natraj, or the dancing Shiva. On the way, we passed a black-and-white photograph of an artisan working on the floor. Naipaul, as if anticipating an inborn prejudice in me, said, “That man, seeming to hammer out the image, would have had all kinds of fine ideas going through his smooth head.”

Naipaul must have guessed my upbringing in India would not have equipped me with an idea of the artist capacious enough to include a medieval artisan, sitting on the floor, fashioning image after identical image. Moreover I was without the means to appreciate the spirit in which objects of devotion had been created in old India. “The purpose of sacred images in Indian art,” writes the Swiss scholar Alice Boner, “is not aesthetic enjoyment. They are focusing points for the spirit. Born in meditation and inner realisation, they should, and this is their ultimate intent, lead back to meditation and to the comprehension of that transcendent reality from which they were born. If they are beautiful, it is because they are true.”

Naipaul followed my eyes drifting over to the Natraj dancing his dance of creative destruction. Walking slowly over to the bronze, with its one leg lifted and turning, its floating hair framed in a wheel of fire, he said, “How did this idea of the twin forces of creation and destruction become enshrined in human form? I don’t know, I don’t know. I don’t think anyone knows. I think the thing just appeared like Venus rolling in from the sea in Cyprus in rock form. It was created wholly by the imagination of men.”

As he spoke, I felt he was repurposing my inborn appreciation for Greco-Roman antiquity, canalising it away from one point in the ancient world to another. In establishing a link between the Natraj and the figure of Venus, he was asking me to look again at something I would have dismissed as a cliché of Hindu iconography. “The image,” he said, “is much debased. It’s used everywhere like some of the Leonardo da Vinci drawings.” His eye fastened on the dwarf upon which the dancing Shiva stood. “I will interpret it in my own way,” he said. “He is standing on the monster of ignorance.”

The theme of willful ignorance had been with us all the while. I wished I had asked Naipaul how he balanced civilisational confidence with the provincialism of believing your world is the only world. How, in his view, could a culture both be outward looking and secure in itself? It was clear that he had certain historical moments in mind: Britain in the 18th century; Islam when it first gained the world; the United States in the 20th century. I suppose the balance was an extremely delicate one.

It had taken scarcely 30 or 40 years for the openness of men like Warren Hastings, the first British governor-general in India, who oversaw the creation of the Asiatic Society, to be replaced by figures like Macaulay, author of the infamous Minute on Indian Education (1835): “I have never found one among them [the orientalists] who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.” In America, too, one could see in real time how a spirit of openness could be replaced by nostalgia and a wish to go to ground.

Naipaul now raised a yet thornier issue that went to the heart of why someone as myself might feel one way about the classical world in Greece and Rome, and quite another way about Hindu India. The Greco-Roman world had died. The acknowledgement of that death had engendered the Renaissance. In India, this was simply not true. The gods had not been overthrown as they had in Greece and Rome by Christianity and Islam. The ancient Hindu past lived on into the present. It meant that the bronzes in the room were not merely objects of beauty, but the active foci of worship. Naipaul understood, better than me, the difference in those ways of looking—that appreciation and devotion were not the same thing.

As we approached a statue of a seated Shiva with his consort Parvati, Naipaul observed those parts of the bronze that had been rubbed to shine.

“It’s, to me, a nice idea,” he said, “rubbing the parts they thought beautiful. There’s no polish…”

“…like the human hand,” Nadira said, finishing his sentence.

I thought of the scenes of devotion and rapture I had witnessed at religious places in India, and wondered if Naipaul, not a man of faith himself, was making common cause with raptures he could never partake in. We moved on to another bronze. It showed Shiva not now in a heroic or symbolic stance but in a relaxed domestic scene, as a husband to Parvati who sat by his side.

Naipaul was a natural teacher, because as a writer he shied away from assumed knowledge. Where a particular way of looking had hardened around a place, or a subject, Naipaul fell back on original sources and tried to come at the problem with fresh eyes.

Aatish Taseer

“Someone asked me,” Naipaul said, seeming once again to anticipate (and be in conversation with), the Western gaze, with all its possibility for denigration, “why these figures have many arms. ’It’s not a human figure,’ I told him, ‘it’s a human figure representing something. The arms are there to represent what is being honoured’.” Naipaul was a natural teacher, because as a writer he shied away from assumed knowledge. Where a particular way of looking had hardened around a place, or a subject, Naipaul fell back on original sources and tried to come at the problem with fresh eyes. In the case of Hindu art, he (more than most) was alive to what the Sri Lankan art historian AK Coomaraswamy, one of his heroes, believed: “To enter into the spirit of an unfamiliar art demands a greater effort than most are willing to make.” It was clear that he had an inborn sympathy for classical India, but he was not prepared to let that get in the way of his critical faculties. Casting his mind back to his comment about how the Hindu gods were not human figures, but expressions of an ideal, he now said, “Here, when the figure has a consort and comes down from its pedestal, things become a little more complicated.”

In another glass case, there were Vijayanagar bronzes. The figures were squatter, thicker of limb. The site of the ruined city of Vijayanagar is where the second of Naipaul’s trilogy—India: A Wounded Civilization (1976)—opens. Naipaul’s idea that India was a Hindu country, battered by centuries of Islamic invasion, and that British rule had helped old India come to terms with what had happened to her, was central to his view of Indian history, and easily the most controversial aspect about it. When a Hindu mob destroyed a 16th century Mughal-era mosque in Ayodhya in 1992, giving rise to modern Hindu Nationalism as we know it today, my mother, in a television interview six years later, asked Naipaul how he felt about what had occurred at Ayodhya.

“Well, I am probably not as horrified by Ayodhya as most people are,” he told her. “I see that Babar was no friend of India, had little regard for India… If you behave in this way you challenge hubris. If you are a builder and a conqueror and Nemesis catches up with you a few centuries later, really, one shouldn’t complain.” The remark caused dismay in India, making people feel that Naipaul was providing intellectual succour to the Hindu Right, but in an odd, highly qualified sort of way, Naipaul was opposed to the demolition of the mosque. “That said,” he added, “let me talk about the other matter, the matter of the invasions and why a political idea of taking revenge doesn’t make sense. I think that after a cultural death, more or less, in India, a revival—a true revival—comes about when we accept that the past is truly dead.”

Naipaul felt that the Dark Ages in Europe had come about because people were not prepared to accept that the Classical World (of Virgil, Horace, and Cicero) was in fact dead. They thought they were expressing continuity, but, as Naipaul said, “Renaissance doesn’t come about by people trying to pretend that the past is still going on. The renaissance comes when people accept the past is over. I think this is where I would probably part company with the political postures of the BJP.”

The BJP, or Bharatiya Janata Party, was ascendant in India and would result in the advent of Narendra Modi’s rule. Modi’s crowning cultural achievement was rebuilding the temple at Ayodhya in 2024. It did not feel like renaissance; it felt like an expression of continuity. And how could it be otherwise? The Hindu religion was alive and well. It served as connective tissue. In what world would India be able to draw a line between past and present, akin to Quattrocento Florence, when India, through the living link of Hinduism, was surrounded by evidence of continuity? “I’m so glad you’re enjoying my VC,” Salman Rushdie replied to me—in an email a few years ago when I congratulated him about his new novel, Victory City (2023), whose Vijayanagar setting made me feel he was in conversation with Naipaul—“which proposes (among other things) that Sir Vidia was wrong about Vijayanagar (as about much else).” Rushdie may well be right, but the interesting thing about Naipaul was that the distinctiveness of his way of looking was so particular to him, his judgments so much those of a writer, and not of an academician or a historian, that it hardly mattered if he was right or wrong. His intensely literary way of treating peoples, as Martin Amis puts it, as if they were people, complete with manias, neuroses, and obsessions, made no claims to infallibility, but was almost always a provocation to thought.

“We were talking of security earlier,” Naipaul began, then, referring to the 16th century destruction of Vijayanagar at the hands of a confederacy of Muslim princes, he said, “They destroyed it, and destroyed it completely. This destruction is made beautiful by the Left. They say that it was destroyed by the Indians themselves. They are so completely degraded, they can’t deal with their own defeat, but we mustn’t let that spoil the beauty of what we’re seeing.”

Naipaul began to get tired. We sat down, Nadira and I on a bench, he on his shooting stick, with its Air India tag still hanging from it. He began to advise me on books I might read about the bronzes. They were all by German and British writers. “It’s cause for shame,” he said, “that Indians don’t write these books themselves.”

“You see, the English speaking people of India don’t come here,” Naipaul said. “They think this is local stuff. They want to go to America and have their self-portrait painted and buy nudes like the Maharaja of Patiala. And then they complain that the British looted them. These were in the viceroy’s house, it was Nehru’s idea to bring them here; it was a good idea, but no one wants to come.” He raised his hands, open-palmed in despair.

The mood excited a story about Coomaraswamy. “His dates are 1877-1947,” Naipaul said. “He was half Sinhalese and rich. It was open to him to start up life as a Mayfair gentleman or in the country, but he decided to devote himself to Indian art. In 1917, when Coomaraswamy was 40, he heard that the Hindu University was being built in Benares. He offered them his, by then vast, collection of Indian art, which he was ready to give them free on the condition they started a chair of Indian art and made him the professor.” Here Naipaul paused.

“What did they say?” I asked, enthralled.

“They told him to go away,” Naipaul said, and repeated, “They told him to go away. They told him to take his art collection and go away.” Here Naipaul laughed, his eyes widening. His laughter rang out, like the laughter of the world at the folly of human beings.

“Where is it now?” I asked.

“It’s in Boston, it’s in Boston,” he said.

A few Indians, middle-class-seeming people with cameras, sauntered in. Nadira took this as an opportunity to challenge her husband’s earlier claim that English-speaking Indians were not interested in India’s antiquities. “Look, they’ve come,” she said.

“They’ve come for the jewels. Yes, yes, they’ve come for the Nizam’s jewels. Their grandparents were taxed to death for the Nizam to have those jewels. And he didn’t do a thing; he just handled his jewels. The Left adores the Nizam.”

Then, suddenly, our visit winding down, Naipaul grew agitated. “You’ll come back,” he said, “and you’ll look at these things, you’ll look at what we’ve seen and then move on.”

He seemed almost in pain at the thought that after this effort of his to show me how to look at Hindu art, I too might succumb to the disregard of the colonised. Years later, in trying to understand how Naipaul (and not Rushdie, say) had ended up an unlikely hero of the new progressive Left, even though they shared none of his positions, I realised that it had to do with how totally he was in sympathy with ordinary people. In India, where there existed all sorts of invisible barriers between the English-speaking well-to-do and the poor, Naipaul changed the air whenever he was around. No one went unseen. Not Pradeep, who worked at the Maurya and who helped Naipaul when he was in India, not the beggars who appeared at our car window at traffic lights. Their poverty was never sentimentalised; never “made beautiful,” as the Indian Left, emerging out of Gandhian and Nehruvian Socialism, was prone to do; it was simply confronted, but when Naipaul said India was unbearable for him, because he always put himself in the place of those enduring hardship around him, I believed him. Walking out, we passed a map of the places from where the antiquities had come. It annoyed Naipaul. His eyes resting on a site in Bengal, he said, “The Calcutta Museum has a good collection, but kept badly. I think they would like to destroy them, but they can’t. So they do the next best thing: they let the workers watch them. Yes, they let the workers watch them.”

Another group of Indians, in bold colours, was coming in just as we were leaving. They seemed from the south, with teekas on their foreheads and flowers in their hair. They were laughing and visibly excited by what they saw.

“You see my point,” Naipaul said. “The people who come are the temple-goers and the ones who stay away are…”

“The Anglicised…” Nadira started.

“The green-card folk!” Naipaul said, and laughed deeply.