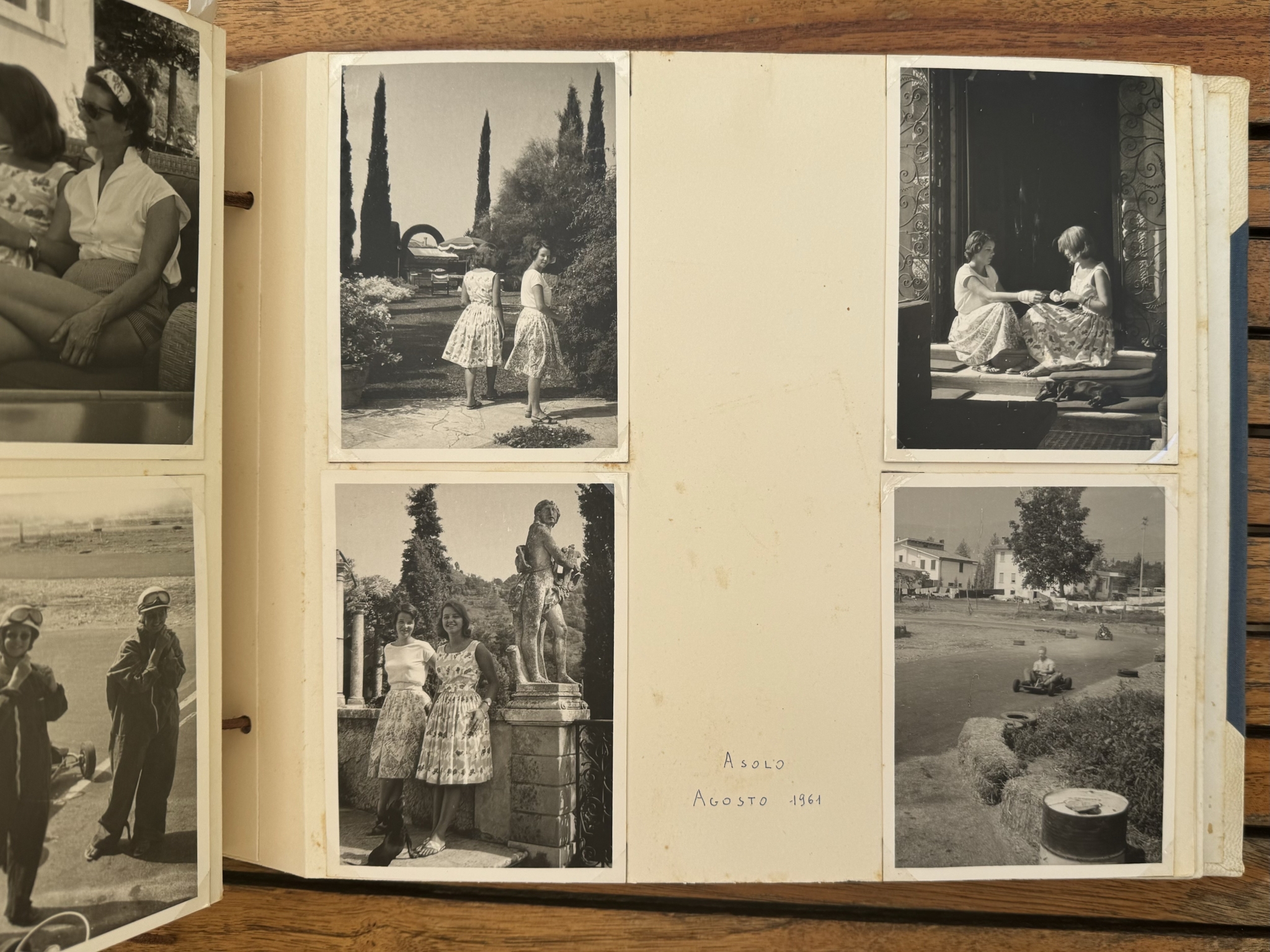

The first page of Slim Aarons: La Dolce Vita shows a photograph of two young girls in the gardens of their family home in Asolo, a small hilltop town an hour’s drive from Venice. The girls photographed are Delfina and Alessia Costa De Lord—granddaughters of one of the old Asolani families who had been asked by a friend of their grandmother to pose for an American photographer who would be passing through the town. I find myself standing in the same place, overlooking Villa Il Gallero nearly forty years later—the gardens now overgrown, but otherwise little changed.

Aarons visited Asolo in 1988, travelling from nearby Maser, where he had been photographing the Palladian Villa Barbero. Like many towns in the Veneto, Asolo keeps itself quiet. Many of its villas were built as summer homes for Venetians seeking fresh air and lighter society, away from the crowds of Venice. On clear evenings, the lagoon appears as a ribbon in the distance—a quiet reminder of la Serenissima keeping watch—yet, Asolo stands apart, a world entirely of its own. Aarons was not the first to make Asolo a muse. For centuries, it has attracted artists, poets, and socialites, all seeking a place of picturesque retreat. Robert Browning finished his final poems in what is now the Hotel Villa Cipriani. Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, and John Dos Passos stayed here during their Italian travels. Freya Stark lived and wrote here in between her journeys abroad, and Vittorio De Sica shot part of his 1968 disaster, Amanti here—a film rated one of the worst ever made, though still much loved by the Asolani.

The approach to Asolo is unassuming, but at a certain turn in the road, it appears: half-hidden villas nestled into the hillside, pale terracotta roofs, tall silhouettes of cypresses, and a faint shadow of purple mountains in the distance. Freya Stark described it best: ‘You never saw anything so lovely as Asolo now […] I came up by a little hill, quite tiny, and grown all over with very small trees bursting with fat bunches of blossoms […] The only adjective for this landscape now is gentile.’ Asolo is a place where everything appears in perfect harmony: the landscape is soft, the architecture modest, and the pace of life leisurely. Henry James wrote that there was ‘no sweeter place in sweet Italy’.

The main road in Asolo is the Via Robert Browning, which opens onto a large piazza where locals and tourists create a constant hum at the Café Centrale. On my first morning, I come here to watch the town over a cappuccino and a brioche. The drinks on the menu are amusingly named after the town’s characters: Hemingway’s Sour, Browning’s Serenade, and Carducci’s Horizon—baffling, I am sure, to the unwitting tourist. I imagine what the piazza might have looked like in its most recent golden period: a glamorous Anglo-Italian set, artistic expats moving easily amongst locals.

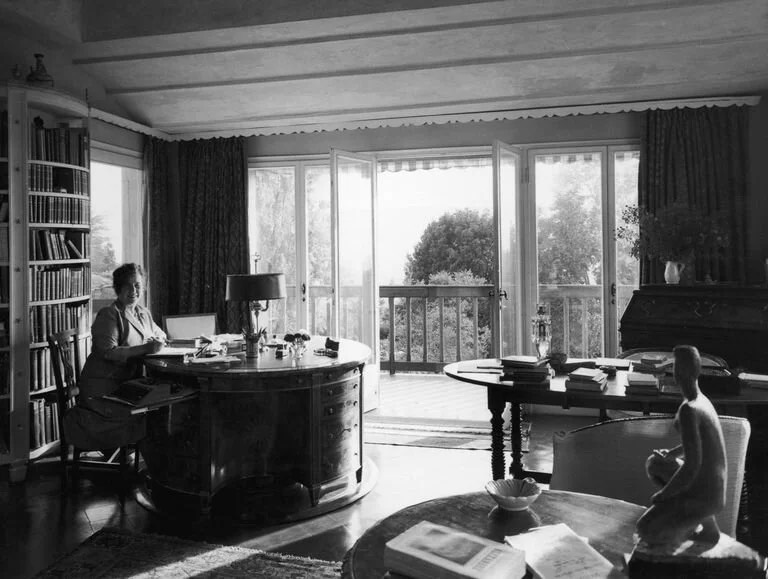

I leave the piazza behind to wander the streets. We pass Villa Freya—where the British-Italian explorer and travel writer lived and wrote in between her travels to the Middle East. I am shown around by the De Lord Rinaldi family who remember her fondly as La Zia Freya. It was always an occasion to call on her at home, they tell me. It was a house which suited her perfectly: books, photographs, and objects everywhere; fabrics from abroad covering every surface. She kept a magnificent garden, too.

Stark’s life was vast, and yet she moved through it with a supreme lightness in her manner, always speaking as though she were your closest friend. She was eccentric, and delightfully so. Her dress sense was all lace, frills, and bows—charmingly out of step with her life’s seriousness. A favourite family story tells of a trip with her to a dressmaker in Padua. She was in search of a dress for a dinner with the Queen Mother in London, but it would have to survive in a suitcase en route to the Middle East. She would choose the most impractical option: an enormous gown of pink, yellow, and blue tulle.

In the evening, we stop at the Hotel Villa Cipriani. Once the home of Robert Browning and later the Guinness family, who would turn it into a hotel with the help of Giuseppe Cipriani, it still carries the air of a private villa. The interior has an old-world charm—the glamour of Harry’s Bar in Venice, another Cipriani institution—but with a quieter, more familial atmosphere.

Down the road is Casa Duse, where the celebrated Italian stage actress Eleanora Duse spent her final years. The townhouse, built into Asolo’s medieval wall, is painted a soft Italian rose, and a simple plaque commemorates her as one of the town’s most beloved figures.

Freya Stark at Villa Freya in Asolo

In Asolo, you cannot take more than a few steps before hearing a whisper of its past. Its story is kept alive in street names, in villas whose residents are never forgotten, and in fond remembrance of its characters. The town is a palimpsest, layered and made rich by the lives lived within its walls.

Carolina Julius

In Asolo, you cannot take more than a few steps before hearing a whisper of its past. Its story is kept alive in street names, in villas whose residents are never forgotten, and in fond remembrance of its characters. The town is a palimpsest, layered and made rich by the lives lived within its walls.

At Villa Il Gallero, the De Lord Rinaldis walk me through their rooms, remembering childhood in Asolo as an endless fête: the house a constant stream of visitors, the dining table always laid for guests, and preparations for some party forever underway. The English, I am told, were especially adored—for the community they brought to Asolo, and their eccentricity at every dinner party.

Asolo has always been a town of visitors. Its first was an exile: Queen Caterina Cornaro of Cyprus, who brought with her a court of artists and intellectuals, and a vision for Asolo which still endures. Throughout the town, the clocktower can be seen rising from her castle—a reminder that Asolo belongs to its own order of time. Robert Browning called it Asolando, ‘to disport in the open air, amuse one’s self at random’.

By evening, the piazza has filled with saffron light—the same light that floods Aarons’ pictures, taken years ago. I imagine there are worse places to spend an exile—I could certainly stay a while longer, asolando.