In the twilight of his career as a writer, the young Albert Camus penned a series of essays that evoke the blazing sunlight of Algeria and the sensuality of the Mediterranean coast. In this essay, we look back at Nuptials and how it came to embody the spirit of a life in North Africa… and how his philosophies on the absurd were shaped under the sun.

In Nuptials (Noces, 1938), a 23-year-old Albert Camus exercises his first interest in themes of the absurd and suicide, written with an exuberant happiness, joie de vivre, and despair. Set against the Algerian coast where Camus was born and philosophically rooted, this selection of short stories is sensually composed with images of luminous sunlight, ruins, and naked bodies bathing on stretches of beach. This sensuality forms a background for his musings on religious hope, the rejection of religion, and life after death, and he advocates for living in the moment—making Nuptials a considerably light series in his canon. In a later preface for the collection, Camus noted that he found the stories to be immature in his articulation of his philosophy, but these lyrical essays are full of a life and a sense of literary colour not seen as vividly in his later, more famous works such as The Myth of Sisyphus (Le mythe de Sisyphe, 1942) or The Plague (La peste, 1947). They are also moving visions of the North African coast and the intoxicating spirit of the Mediterranean.

In the opening of the 1950 edition, Camus writes: “This edition reproduces these [essays] without any changes, in spite of the fact that their author has not ceased to consider them as essays in the precise and limited meaning of the term.” The first of four essays is Nuptials in Tipasa (Noces à Tipasa), set among the Roman ruins of Tipasa; a dream-like description that becomes a celebration of one man’s visceral attachment to his environment. This is the first time his beloved Algeria is used to articulate his philosophical ponderings. There is a travelogue within these pages, and references to ancient gods Dionysus, Demeter, and Eleusis. His sense of a world where myth overlaps natural splendour is expressed candidly. Overlooking the ruins and the sea, he writes: “Here I understand what is glory: the right to love without limits… The breeze is cool and the sky blue. I love this life with abandon and wish to speak of it boldly.”

The second story is The Wind at Djemila (Le vent à Djemila). Like the previous essay, he homes in on a particular place, in this instance the village and ruins of Djemila—a UNESCO protected site in the mountains northeast of Algiers. But among the towering and lonely Roman columns, Camus is transfixed by death and the hopelessness of the “dead town”, and his ideas here are easily linked to his future theory of the absurd and the dilemmas of his character Meursault in the great work The Stranger (L’etranger, also published in English as The Outsider, 1942). In Djemila, a hard wind grazing his eyes, he realises the indifference of the natural world that would play into his notions of the absurd. He writes: “I tell myself: I am going to die, but this means nothing, since I cannot manage to believe it and can only experience other people’s death. What does eternity matter to me?” But in the same breath, he also confronts these thoughts in a stoic manner and faces the absurdity of the human condition with total clarity: “I have no wish to lie or to be lied to.”

Albert Camus, 1952. By Michael Ochs.

It was around this time that Camus conceived of the condemned Meursault’s conversation with the prison chaplain. It echoes from Djemila to the jail cell. “Have you no hope at all? And do you really live with the thought that when you die, you die, and nothing remains?” the chaplain asks. Meursault answers in the affirmative. The chaplain replies it is more than a man can bear. But it is a wager that Meursault—and Camus himself that day at Djemila—is willing to make.

Next is Summer in Algiers (L’été à Alger). If The Wind at Djemila was a philosophical well for his ideas of the absurd to spring from, the setting of his beloved Algiers in The Stranger and The Plague are expressed most vividly here as a self-portrait. Camus grew up in the working-class Belcourt quarter, in a humble apartment on the Rue de Lyon that he shared with his mother, brother, grandmother, and uncle. For a French pied noir, he was little better off than the native, colonially oppressed Algerians, and his kindred attachment to them is described in this tribute to the lavish splendours of Algiers—the White City.

In Summer in Algiers, first published in 1950, he wrote of his “instinctive fidelity to a light in which I was born, and in which for thousands of years men have learned to welcome life even in suffering.” Sunlight and poverty would remain vitally important for Camus across much of his work. But poverty in the city is a playground; an opportunity to treat the day as if there is no consequence or end, flirting with “brown-limbed girls” on the beach, and paddling around the industrial freighters in the port. He describes the music hall by night and the white-cubed buildings of the Casbah.

In Algeria, passages like these continue to make Camus a controversial figure; he sometimes treats the natives with faceless descriptions, often from the perspective of a French colonist. His stance against the Algerian revolution further complicates his legacy. In Algerian intellectual circles, debates continue on whether to accept Camus as an “Algerian” worthy of their postage stamps. Yet Summer in Algiers remains one of the truest descriptions of life in the city, illuminating the sunlight and poverty that shaped his world view.

If Camus once described the novel as “philosophy expressed in images”, these essays confront us with philosophy expressed through the senses. Following Summer in Algiers is The Desert (Le désert)—the final and truest essay of the selection. No longer in Algeria, Camus overlooks the Boboli Gardens in Florence, musing how the “world is beautiful and outside there is no salvation.” His desert is a world unto itself, where the wonders of poetry, myth, and art live. Beyond the desert, the empty quarter he can fill with his imagination, there is nothing.

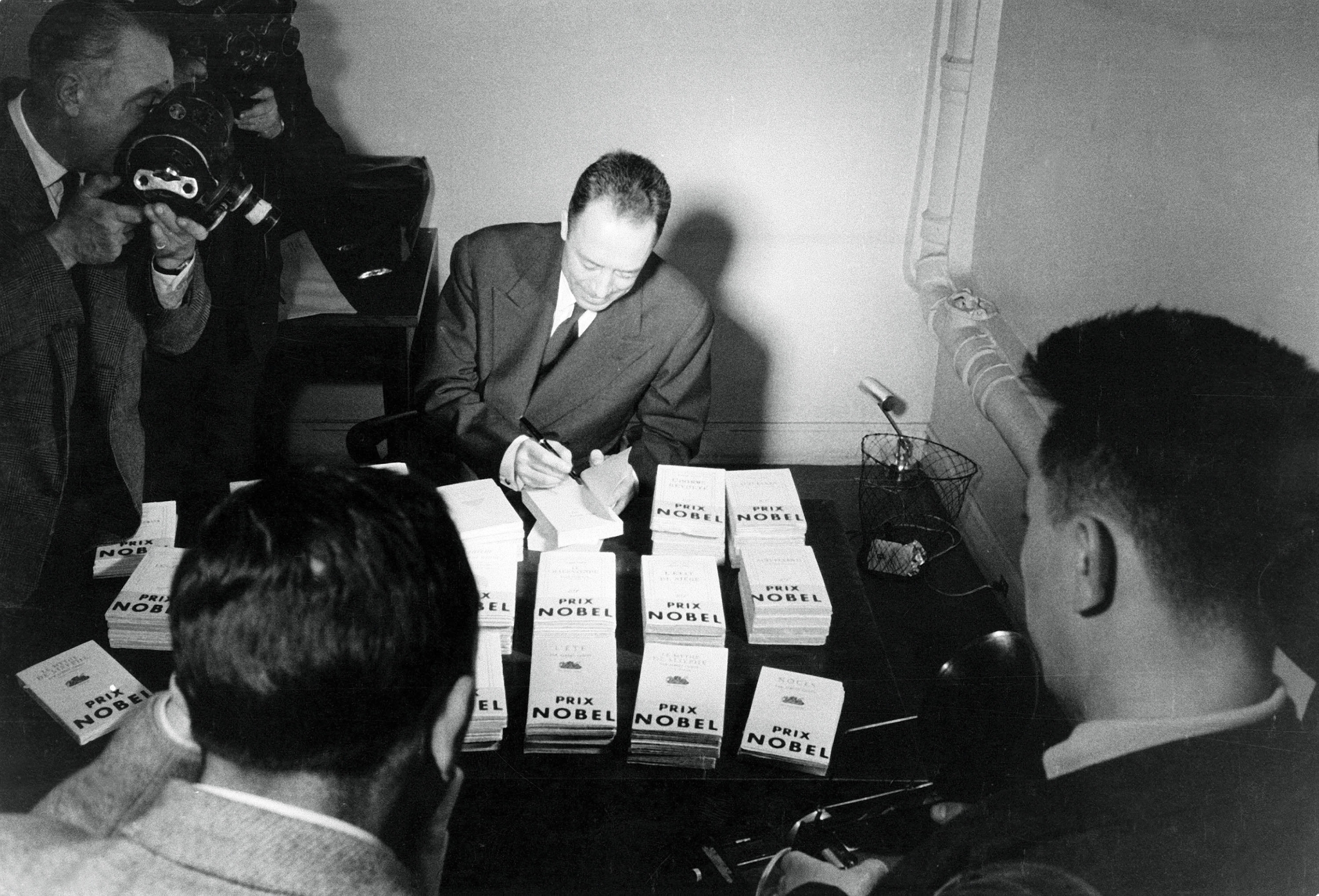

Camus was young—just 46—when he died on 4 January 1960 in a car crash. His publisher Michel Gallimard’s Facel-Vega slid off the Nationale 5 road 15 miles outside of Sens and slammed into a tree. Both men were killed. Not long before, Camus had won the Nobel Prize for Literature—a prize he considered premature. He had longed to return to Algeria, away from the reactionary Paris intellectual circles who had shunned him. “I want to disappear for a while,” he said to a friend. It was a morbidly prescient request.

Speculation aside, Camus’ rawest form lives on in Nuptials—the expressive lyrical essays that channel the natural world he found so potent with the ideas of death and the absurd that would shape his being, and so many readers since. From the coast by Tipasa to the arid mountains of Djemila, the bawdy port of Algiers, and the empty desert of his imagination, Nuptials is the unsculpted philosopher finding himself, and where, for so many readers, a source of endless comfort and sensual enlightenment remains.