The birth of modern dating is intertwined with that of cinema. From teenagers in 1920s New York hanging out in newly minted movie theatres to the mid-century cultural script of “dinner and a movie” and the picturehouse as a site for queer cruising, the dark corners of the cinema have long been a sanctuary for lovers. Maxime Toscan du Plantier reports.

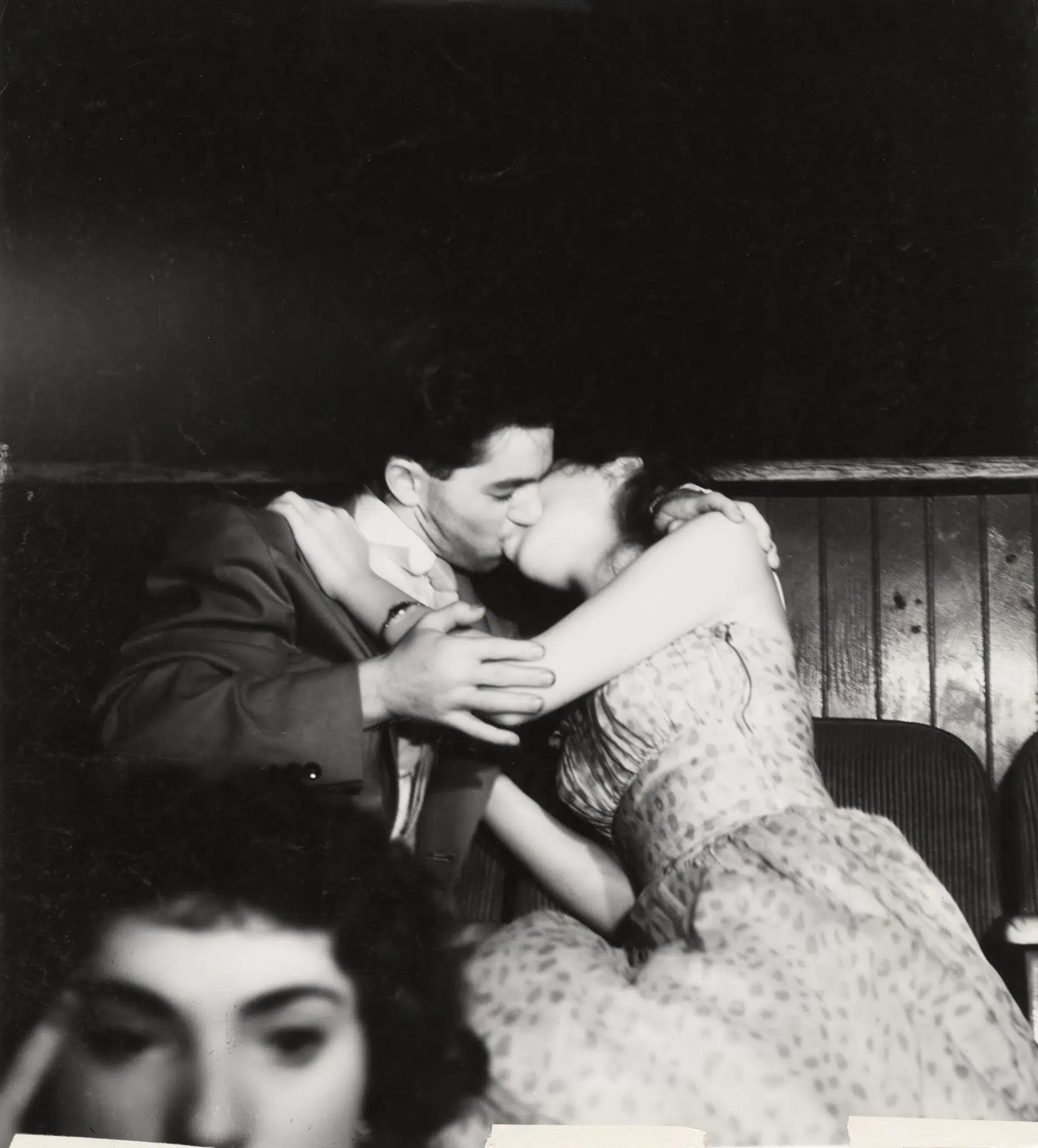

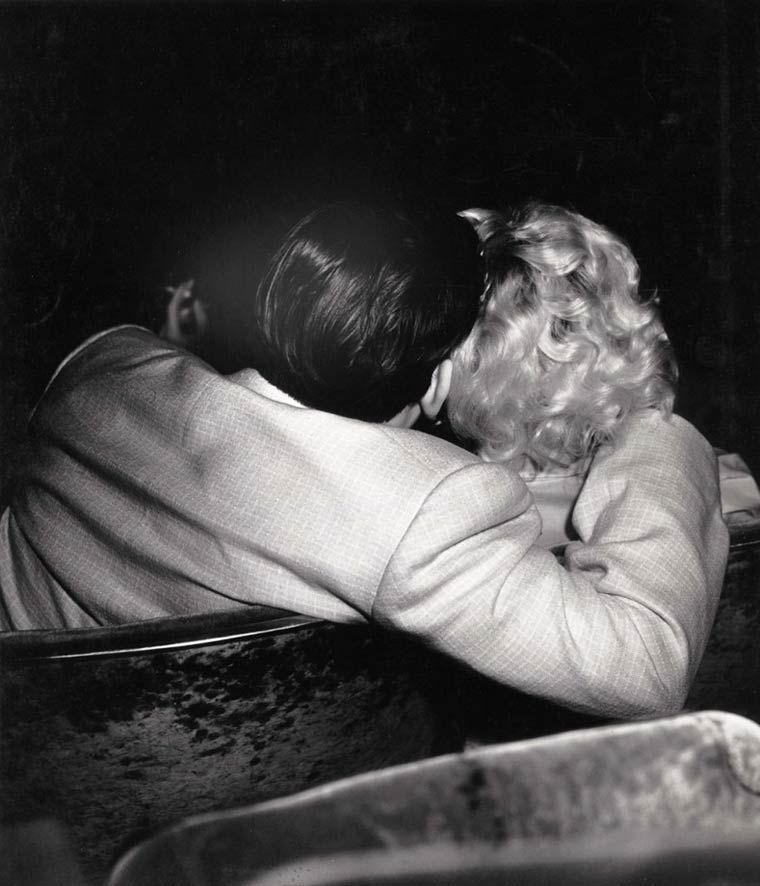

The scene is familiar. A couple, usually teenagers, sit down with a large bucket of popcorn. The lights are turned off, the movie starts and, with it, begins a delicate choreography. Elbows, hands and legs brush against each other, with the aforementioned popcorn-eating acting as a convenient facade for what is really at stake. Then comes the time for more prolonged hand contact; sideways glances slowly escalating into outright stares and, eventually, when the plausible deniability offered by the sitting arrangement and snacks reaches its utmost limit, the kiss comes. And sometimes more.

The scene is well-known because it is, itself, a movie trope. In an art-form that has always been drawn to self-representation, examples abound. From Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. (1924) and David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945) to Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso (1988) and Damien Chazelle’s La La Land (2016), movie characters have always dated and kissed in cinemas. But, unlike jumping onto a moving car from a highway bridge, kissing in a cinema is not only a screenwriter’s invention. In fact, the birth of modern dating is intertwined with that of cinema.

Once upon a time, there was no dating. As every Bridgerton, Gilded Age or Jane Austen fan knows, courtship in 19th century America and Europe was organised around ‘calling’. After having met at a ball or another private social event, a man could earn the right to ‘call’ at a young woman’s house where they could discuss in the parlour or drawing room, under the watchful eye of a family member or chaperone. This required, however, to have a room fit for visitors, something which working-class people did not have in early 20th century New York and other cities along the East Coast.

Around 1910–1920, young working-class New Yorkers started meeting in public spaces instead of private homes, historian Beth Bailey explains in From Front Porch to Back Seat: Courtship in Twentieth-Century America (1988). Dating was born, first as an economic necessity, but was quickly adopted by New York’s privileged youth who saw in it a way to escape their families’ controlling gaze. Among the public spaces where such encounters could happen were the dance halls (as seen in West Side Story), but also the newly-born movie theatres.

For young women, the allure was obvious: the darkness afforded privacy while the presence of other people allowed them to retain a sense of safety and respectability. In 1909—only 14 years after the first public film screening by Louis Lumière—Rollin Harte wrote in The Atlantic about the ‘motion-picture theatres’, remarking that ‘the semi-darkness permits a “steady’s” arm to encircle a “lady friend’s” waist’. Cinemas became the place to peck. In 1927, a North Dakota visitor in New York wrote to the Bismarck Tribune that ‘a dark corner of a movie theatre’ had become young people’s favoured place for such activities and, the same year, Variety echoed a complaint that ‘One cannot go even to the best picture houses in the city without having to blush for the actions of young people in the audience.’

By the 1930s, Bailey explains, the American middle-class had adopted dating as the norm, with movie theatres at its centre. ‘A dinner and a movie’ or ‘a movie and a coke’ became a recognised cultural script. This was not limited to the USA. In her autobiography, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, Simone de Beauvoir describes watching with envy groups of young men and women going to the cafés and cinemas of the Saint-Michel neighbourhood in Paris in the 1920s, something which her conservative parents did not allow because they feared cinemas’ licentiousness.

For young women, the allure was obvious: the darkness afforded privacy while the presence of other people allowed them to retain a sense of safety and respectability.

Maxime Toscan du Plantier

The postwar automobile boom led to the creation of drive-ins, which came to represent 40% of cinema tickets sold in the U.S. The backseat of a car allowed more legroom than a traditional cinema, and drive-ins quickly acquired the reputation of being ‘passions pits’, with ‘better shows in the cars than onscreen’ as historian David L. Lewis wrote in 1983. The sexual expectation could lead to unwanted pressure or misunderstandings. In Grease (1978), Sandy (Olivia Newton-John) barges out of Danny’s (John Travolta) ‘sin wagon’ when she realises that his invitation to the drive-in was never about the movie.

By the 1970s, studios were explicitly catering to the dating audience, with a new genre designed for them: teen slashers, whose successful franchises included Halloween (1978), Friday the 13th (1980) and Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) Film historian Richard Nowell explains that their strong female lead was supposed to give women in the audience someone to identify with, and the horror part provided a ready-made excuse for physical contact. Nowell quotes a studio executive who said: ‘You can never go wrong with a movie that makes a girl move closer to her date.’ It was also an opportunity for each to mirror the on-screen gendered roles as spectators—the young woman acting scared and the man showing his unflinching masculine bravado. I remember that studio executive’s remark still being passed on as some secret lore during my teenage years in Paris, and trying (helplessly) to look unfazed during a group watch of James Wan’s Conjuring (2013).

Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. (1924)

This history is not limited to straight culture. Cinemas have also played an important role in the development of twentieth-century gay culture. In Gay New York (1994), historian George Chauncey explains that from the 1920s onwards, gay men started meeting in cinemas for the exact same reasons as the working-class youth. Cinemas afforded the privacy and anonymity one could not find at home, and escaped the NYPD’s aggressive surveillance of gay men in parks and restaurants. Particular cinema balconies or bathrooms became known in the ‘sexual geography of the neighbourhood’ as places for gay encounters. (An idea captured in Tennessee Williams’ 1941 short story ‘The Mysteries of Joy Roy’) The phenomenon was not limited to New York. In the same years, cinemas in London, Berlin, Mexico City, and Rio de Janeiro became havens for gay men looking for intimacy.

There is no equivalent record for lesbian women, but filmmaker and scholar Andrea Weiss described how Hollywood’s innuendos ‘at the possibility of lesbianism’ have allowed generations of women ‘to explore their own erotic gaze without giving it a name, and in the safety of their private fantasy in a darkened theatre.’ She mentions Marlene Dietrich’s gender-bending cabaret performance in Morocco (1930), in which she kisses a woman in the audience.

Damien Chazelle’s La La Land (2016)

Later, however, the emerging lesbian counter-culture of the 1960s and 1970s seems to have rejected dating at the movies because of the practice’s already-established association with heterosexuality. In When We Were Outlaws (2011), her memoirs set in 1970s Los Angeles, lesbian activist and writer Jeanne Córdova systematically associates going on movie dates with the ‘norm’. She ironically describes going to ‘a matinee movie and dinner’ as being ‘normal lesbians on a weekend’ and remembers a partner asking her to go to a movie ‘or do something normal like other people do’, instead of doing the ‘gay revolution’ all the time.

Meanwhile, the development of pornographic theatres in the 1970s accentuated cinema’s role in gay culture. In his autobiographical essay Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (1999), Samuel R. Delany explains that although (or because) they showed straight porn, these cinemas became exclusively male meeting places where sexual activity could happen openly. In New York, this was centred around the porn theatres of Times Square and West 42nd Street. ‘The Deuce’, as the area came to be called, was captured in John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) and later in HBO’s The Deuce (2017-2019).

‘A dinner and a movie’ has been replaced by its privatised and individualised doppelgänger, ‘Netflix and Chill’. The pandemic undoubtedly accelerated the process, keeping a whole generation away from cinemas for years.

Maxime Toscan du Plantier

However, Delany’s book captured a bygone era. Under Rudy Giuliani’s mayorship between 1994 and 2001, the city of New York ‘cleaned up’ and gentrified the area, closing the pornographic theatres and relocating working class residents in favour of a private conglomerate led by the Walt Disney Company. Delany concludes: ‘With the rush to accommodate the new, much that was beautiful along much that was shoddy, much that was dilapidated with much that was pleasurable, much that was inefficient with much that was functional, is gone.’

Times Square is only representative of a wider trend. In Hooking Up, sociologist Kathleen Bogle explains that traditional dating is being replaced by a ‘hooking up culture’ among young American men and women. For them, the idea of ‘somebody picking you up, bringing you flowers, taking you out to dinner and maybe a movie’ is outdated and laughable. No one wants to date like their parents did. ‘A dinner and a movie’ has been replaced by its privatised and individualised doppelgänger, ‘Netflix and Chill’. The pandemic undoubtedly accelerated the process, keeping a whole generation away from cinemas for years.

Yet, there is a case to be made that dating at the cinema is more relevant than ever. By programming the release of Emerald Fennell’s upcoming Wuthering Heights on February 13, Warner Bros might be betting on the return of the movie date. As co-star and producer Margot Robbie said in a recent red carpet interview: “If it was me, I’d want to go with all of my girlfriends on a Friday night…and then I’d want to go with my husband or whoever on Valentine’s the next night.”

In these times of generalised housing and cost-of-living crises, forcing many to stay with parents or flatmates longer than they would like, cinemas offer a particular form of sanctuary. They are a place to meet one’s crush, date, lover, or partner, a space to experiment and lean into erotic desire—even if it’s just until the credits roll.