In a never-seen-before interview, Andy Hazel spoke to the late, great Robert Redford about childhood, freedom and living in dark times.

In 2019, the Marrakech International Film Festival opened its doors to a parade of auteurs, actors, and industry grandees, each carrying their own claims to the lineage of cinema. Yet amid this global gathering, one presence felt singular: Robert Redford. He was the kind of actor for whom the word “star” seemed both too small and too grand. Redford himself always resisted the label, insisting that he came not from Hollywood but from Los Angeles, a boy shaped by the years of war, who came of age in Paris, and found nascent fame on Broadway in his late 20s. But the paradox of stardom is that sometimes the title frees you more than it confines you, and Redford used his influence to build something bigger than his own career: a lifeline for independent film through Sundance.

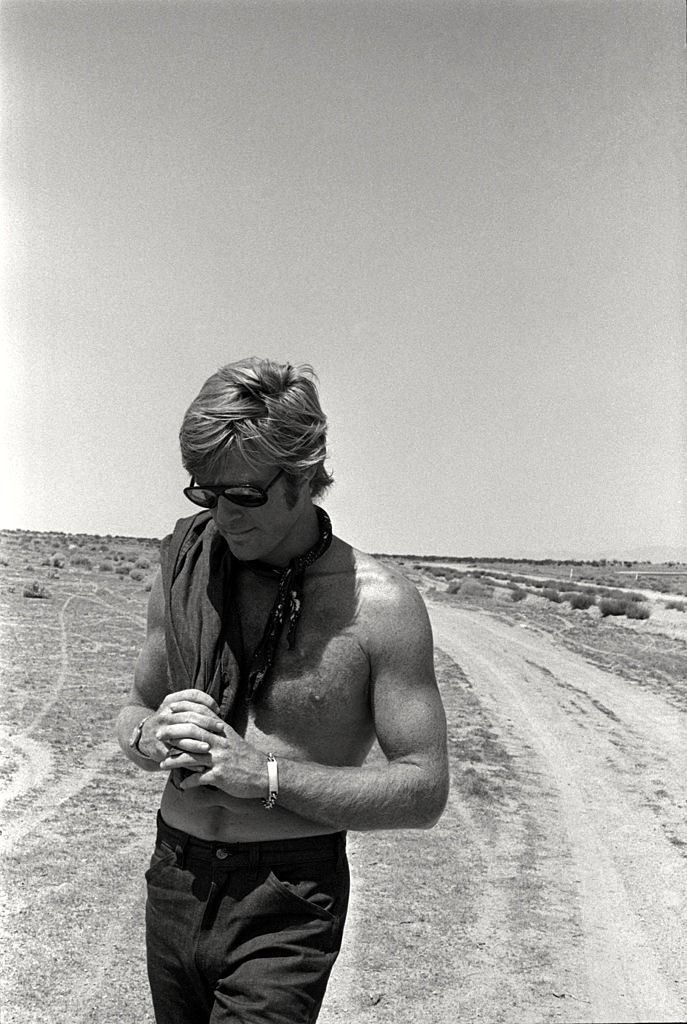

Redford spoke with the quiet authority of someone who had lived fully in cinema’s shifting seasons, from the radical currents of the 1970s to the quieter retreat of his New Mexico home, where he sketched and listened to the desert’s silences. He preferred to face forward, to think about the work still to come, but when coaxed, he could revisit the films and friendships that shaped him and the risks he took that he credited with his success. And always, his thoughts returned to the ideas that defined him: freedom, truth, and the cost of both. This interview was one of the last longform conversations he gave before his death earlier this week at the age of 89, and it remains unpublished until now.

Robert Redford: When I was a child, I thought, I can’t wait to be an adult. All you think about is growing up, getting older, responsibility and so forth. Then you get there and you feel like something is missing. And what’s missing is the dreams and enjoyment of your childhood. That has always stayed with me. I didn’t understand it at the time, of course, but later you realise those dreams are the part of childhood you can’t get back. You spend the rest of your life, maybe, trying to recreate some of that wonder.

Robert Redford: A Walt Disney film, when I was a little kid. This was during the Second World War and we had no television, only radio. So, you would walk to a theatre to see a movie. For me, that was an incredible experience. You couldn’t wait for the weekend, because that’s when you would go. I miss that. What I miss is that feeling of walking into a theatre, sitting in the dark with other people around you. The lights would go off and you would look at this big screen and you would see magic happening on that big screen, and you would feel the energy of the people around you. That collective excitement. That’s pretty much gone. With television, with streaming, viewing is easier and quicker, but something has been lost. The anticipation, the waiting, the magic of sharing that experience with an audience, it’s very different now.

Robert Redford: When I was young, I wasn’t politically sophisticated. When Vietnam came, with the draft, it affected me, because you had to go, you know? It was your duty as a citizen. At that time in my life I was too absorbed in my own career and the need to get what was in my head out into the world. I wanted to create art, and politics felt like a waste of time. Later, through filmmaking, I realized politics was a worthy subject — questions like do you go to war or not? were honest debates. When I was young, my thinking was narrow, I was always against, rarely for. As I grew older, I saw life was more complicated, and I came to understand the role art can play. Art, in its broadest sense, criticizes society. It draws attention to truths, to facts, and keeps us honest. It offers another point of view when things tip too far one way, as they did during the Nixon years, and as they do now. Without that balance, what you stand for begins to erode. That’s why the search for truth is so important.

Robert Redford: My memory goes back to the end of the Second World War. I was five, six years old. I remember the energy then. Everyone in America was gathered together to raise money, to sacrifice for the greater good; to fight fascism in the other part of the world. I didn’t understand what it was all about, but it felt good. It felt good to be gathering papers and putting them in a pile, knowing it was going to be used for something that was good for your country. That was my memory of the war. That, and once a week going to the movies. Waiting for a Walt Disney film. That was my excitement. Those memories shaped me. The sense of unity, of everyone contributing, it’s very different from now.

Robert Redford: It wasn’t an accident. To me, back then, the idea of being an actor was the idea that you could feel a sense of freedom. You were free to be someone else, free to act as someone else. And if you were paying attention to the people around you, you noticed types. Then suddenly you had the chance, as an artist – because acting is an art form – to say, I love this character, I’ve seen this kind of person before, now I’m going to embody them and bring them forward. That freedom was what drew me in. To embody others, to live another life for a while. That was appealing.

Robert Redford: That’s a good question. It’s tricky. You might say, I want to be free from ideology, free from certain things, and in doing that, you reject what is good. If you reject everything in the name of freedom, you risk losing something valuable. Truth is tricky too. We all want it. It’s a natural desire: I want to get to the truth. But how do you know when someone is really telling it? Everyone claims to. That’s where the drama is. I think you can dramatize that. That’s what The Company You Keep (2012) tried to do.

Robert Redford: Not really, no. I’ve always been forward thinking and forward moving. I didn’t spend much time on the past, unless there was some value in bringing it forward in storytelling. But there are moments that have stayed with me. I was very fond of F. Scott Fitzgerald. I had the pleasure of being in The Great Gatsby. There’s a line where Nick Carraway tells Gatsby, ‘You can’t repeat the past,’ and Gatsby replies, ‘Can’t repeat the past? Of course you can.’ I love that moment. Gatsby was obsessed with an image of the past – his love of Daisy – but it’s no longer the past. That line meant a lot to me. Because it captures something about human beings: we want to repeat the past, we want to hold on. But time moves only forward.

Robert Redford: I believe in risk. Not taking a risk is a risk. It’s the only thing that moves you forward. If you don’t take it, you stagnate. When you take a risk, you don’t know how it will turn out. You don’t know where you’ll end up. That’s frightening. But it’s also the only way to grow. As an actor, you might take on a character who is unpopular, isolated, someone with a point of view very different from the norm. That’s a risk. But if you commit to it, it can be wonderful. That’s how you keep the craft alive.

Robert Redford: It shows shallow thinking. I grew up in Los Angeles but never felt part of Hollywood. I wanted New York theater, Europe, independence. That’s why I founded Sundance. I wanted to celebrate people being ignored, people who deserved a chance. At the time, there was no category called independent film. So we created one. Sundance was about giving those filmmakers a chance to grow.

Robert Redford: It’s when you completely sink into the role, wear it like a coat. You research, you embody it. Sometimes you lose yourself. That’s the risk. If I really took a role seriously, I lost myself in it. That was exciting, but it meant giving something up. You have to commit fully, and that’s what makes it great.

Robert Redford: Well, I remember concluding about how I wanted to use a camera when I saw a documentary that was made by a team of filmmakers called D.A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock. They had a new idea: instead of being outside a situation, observing, you go inside it, part of the action. I was struck by that. That feels really good to me because it’s much more active. You don’t know what’s going to happen next. That’s what I decided when I had the chance to make a film, I wanted to have that same feeling. I wanted to make it like you were in the scene yourself. I had been an artist before I became an actor, so I think that made directing come a little easier to me. My art form was just traveling around, sitting in bars or cafes with a sketchbook and watching people around me, sketching them, and those books kept me company. When I first came to France it was to study when I was a teenager. I was alone, I had no friends, and I did not understand the country at that time, because France was very angry with the United States politically because of something Eisenhower did. I can’t remember what, but I didn’t know that at the time. All I remember feeling was that I was not well. I would go to different places and I would not be able to engage easily with people. So I became more lonely, and I would use my sketchbook as a companion. So, I would sit in a bar or cafe and I would watch people, I would sketch them on the right side of the page, and on the left side, I would imagine what they were saying. I try to put the two together because that was my way of trying to get in the picture, trying to get in the way things were. That turned out to be very valuable for me later on when I became a director, because I had to have that same point of view, being on the outside looking in, but also being able to go in to complete the picture.

Robert Redford: More than ever. Since I’ve kind of retired from film, I’ve said, okay, I’ve done that. That’s 50 years of my life. I’m very proud of that time of my life, but also, you want something fresh. So for me, going back to the way I started sketching and drawing was fresh. The only trouble with retiring is that you should never announce it. You should never say, okay, I’m going to retire now. Then you have a lot of people winding up saying, oh, before you go, could you just do this? Could you just do that? You should just retire and not talk about it.

Robert Redford: There is one project I have that I had for a few years that’s a really, really interesting topic. I developed it and I was originally going to direct it. It’s called 109 East Palace [an adaptation of Jenet Connant’s book 109 East Palace: Robert Oppenheimer and the Secret City of Los Alamos], and it’s about an address in New Mexico at Los Alamos. The atomic bomb was developed and Oppenheimer was the chief guy. So I thought it was such a great story. As I got closer to it, I thought, maybe I’ll just produce it and not try to direct it. I’ve gone back and forth because I still love the story. Oppenheimer was seen as a hero in the 1940s, then by the 1950s, in the McCarthy era, his past associations made him a target. Suddenly the man who had been celebrated was vilified, and Congress went after him. To me, that turn — how political climates can change a person’s standing overnight — is a powerful story. I still have the project, but I’m in a quandary. Part of me would like to direct it because it’s so character-driven. The other part says no, you’ve stepped away from directing. So which part wins? I don’t know.

Robert Redford: That’s the bottom line. Who do you trust? There are so many stories being told, so many claims to truth. Everyone says they’re giving you the truth. But somebody isn’t. Somebody’s lying and you have to figure out who and why. That’s why journalism is important. Journalism is supposed to question the truth. And that’s why I respect it. If you accept what you’re given without questioning it, you can end up in a very dark place. It’s always healthy to question the truth. Very often it is the truth, but not always. Questioning keeps us honest. I think I’m quite socially conscious. Because to be socially conscious means you’re paying attention to the powers that are above you, the powers that kind of control much of your life. So therefore I think it’s very healthy to always be questioning those powers.

Robert Redford: With Sundance, I think the goal was very simple. For me, I wanted to celebrate people that weren’t being celebrated. Celebrate people who are either being ignored or undiscovered, who deserve to be discovered. And at that time, in 1978, there were a few independent films out there, but they had no traction. There was no real category called independent film. Because I had been in the mainstream in my career, I was always interested in the alternative point of view. I was always interested in the idea of independence, and I’ve always been very sensitive to supporting people who didn’t have an opportunity and who deserved one. So I thought, okay, now I have the ability, because of the success I’ve had in the mainstream, to support this area that’s not being supportive of independent films. When I started the Sundance Institute, it was a non-profit institute to support independent filmmakers who didn’t have a chance to grow or develop because there’s no category to support them. So the idea was to create a mechanism that would help develop their stories, help develop their skills so that those films could get out into competition.

Robert Redford: Directing is a chance to control your vision. As an actor, at a certain point, you have to give control. No matter what you’re thinking, someone else is going to direct you. If you have an idea in your head, no matter how good it is, you’re just an actor. So, when I was an actor and I had an idea about a film and it was taken away from me because the director would go in a different direction, I would always feel remorse and then I’d think, maybe I should have directed that, so I could control the idea. When that finally did happen, with Ordinary People, I developed a film where I was the first film I could direct, what was in my head. I thought, imagine all the other people out there, all the other filmmakers out there, that are not being given a chance, that have an idea that’s different from the mainstream. Maybe there should be a category for them. Maybe I can help create that category so that I can promote it. And that led to the idea of a film festival that would be focused, mostly focused on independent film.

Robert Redford: Families are complicated. That’s what makes them dramatic. Ordinary People was about the consequences of someone unable to connect with their feelings. Mary Tyler Moore’s character had two sons. One was her favorite, and he died. She couldn’t deal with it. To keep him alive, she ignored her other son. The damage from that was enormous. There’s a line: ‘Don’t blame your mother for not loving you more than she’s able.’ That was the key. She just couldn’t go there. And the consequences fell on the living son. There’s also Donald Sutherland’s character. He was passive, loving, supportive. But when he realized his wife could never change, never be vulnerable, he had to question whether he loved her anymore. When he says, I don’t think I love you anymore, that was a heavy moment. And her response — to pack and leave — showed the depth of the tragedy. The film was about feelings and what happens when you can’t express them.

Robert Redford: I think probably Sydney Pollack, because of our close relationship and our mutual trust in one another. He understood me as an actor because he had been one and we had grown up together as actors, so he really got me. I trusted him as a director and that bond really mattered. George Roy Hill, too. If you look at his films and you look at some other directors, films that are getting all this attention, sometimes what you’re really seeing is in other directors is their work is kind of more one dimensional. It’s good, but it’s always the same thing, the same group of people, the same things. George Roy Hill – Butch Cassidy, Slaughterhouse Five, The Sting – he was all over the map. If you really look at his biography – and I’m sad that not more people have – he rises very up to the top. Other directors doing the same thing repeatedly got more attention. Hill deserved more. I get sad about that.

Robert Redford: I was very close to Paul. We became very good friends based on our experience as actors working in films together around the same time. In Butch Cassidy, I was 29 years old and Paul was 42, and of course he was considered a star at that time and I was not. So the studio did not want me in the film. George Roy Hill did. So finally it came down to, okay, the studio is going to fight this. George said, I need Paul to push this over the line. I had never met Paul. So we went to meet Paul Newman in New York, went to his apartment, and Paul and I had the chance to spend some time talking. At the end of that, Paul decided, I think I would like to do it with this guy. So he then told the studio that he would support me being in the film. From that point on, I had a great deal of affection for him because of what he did for me that he didn’t have to do. So we did the film together and things just fell into place. What a lot of people haven’t realized, what I’ve been surprised that a lot of people, particularly critics, have not picked up on, was the next film we did was the Sting, and the roles were completely reversed. In Butch Cassidy, I played the cool guy and he’s the happy go lucky guy. In The Sting, I’m the happy go lucky guy and he’s the cool guy and no one’s picked up on him.

Robert Redford: I think it’s obvious to anyone who reads the news. It feels like there’s a dark wind blowing through all countries, and certainly through America. It feels especially dark because I see freedoms I’ve cherished being threatened. Threatened by overpowering ego. By one-dimensional thinking. By inexperienced people running things. By people assuming power they’re not qualified to hold. That’s why it feels like a dark time.

Robert Redford: Pay attention. That’s the most important thing. If someone asks me for advice, I get nervous. I don’t feel qualified to be giving advice. But if I had to, I’d say: pay attention. God is in the details. I kept hearing that phrase. And I thought, if that’s true, then I should be paying more attention to details. Normally, when you’re walking, you’re looking ahead, toward a goal. But then you miss what’s at your feet. I do like to walk a lot in my place in Santa Fe, New Mexico, there are long, long trails that go into the mountains and through the desert. So, you have a lot of time to walk and think, but also to pay attention. And sometimes we’re so busy thinking or so busy looking forward, we’re not paying attention to what is around us. So a few months ago, I started thinking, okay, when I go for a walk now, I’m going to think more about what’s close to my feet than I might be missing. I did that and I realised I was discovering things I had never seen before, but they were always there. So suddenly I felt like I opened up a whole new dimension to my life by paying attention to the details. That’s what actors need to do, that’s what directors need to do, that’s what citizens need to do. Pay attention.