Sora’s quietly powerful coming of age dystopia has friendship at its core and revolution in its veins.

The filmmaker Neo Sora is telling me a story about K-Pop girl group Girls’ Generation, and how their 2002 song ‘Into The New World’ became the soundtrack for resistance in South Korea. “There was a popular video circulating a few years ago,” he says. “1600 heavily-geared police officers were entering Ewha Womans University, where a peaceful protest was taking place, and all these young women in their 20s formed a human chain and sang this Girls’ Generations song. To this day, it’s still a protest song in Korea. It’s now the generational protest song.”

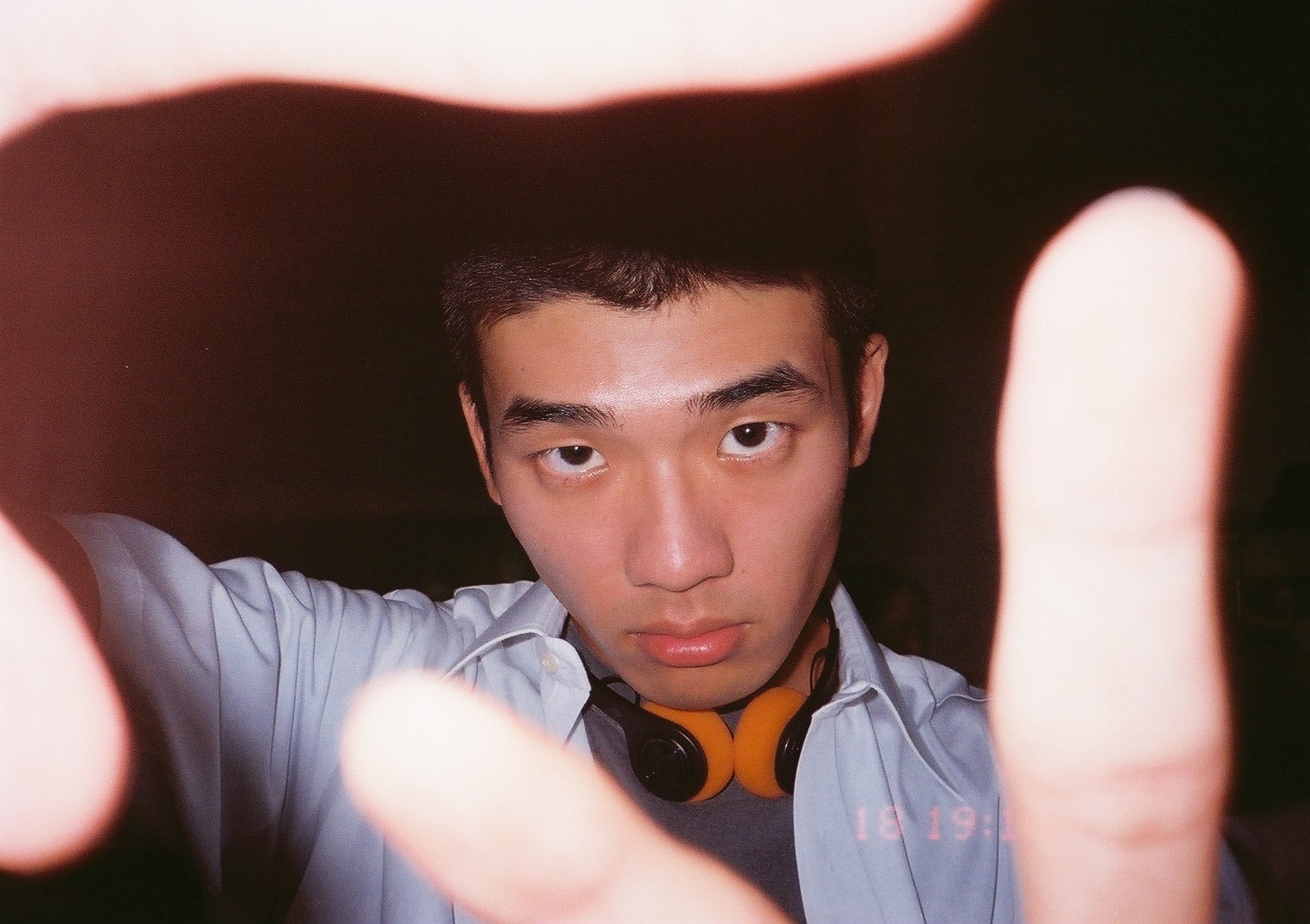

Sora’s first fiction feature (he previously directed his late father Ryuichi Sakamoto in the concert film Opus), the quietly powerful coming of age dystopia Happyend, is about to open in UK cinemas, after a long promotional tour that started during the Venice Film Festival, where the film premiered, over a year ago. “I feel like the movie is finally complete,” he smiles. “Films are fully complete when they reach the minds of the audience. I’m excited to finally put it down and move on to the next thing.”

The film may finally be reaching its completion for Sora, who first conceived of the film over eight years ago (“the first memo I found on my iphone was in 2017,” he laughs) but for most audience members around the world, the story of Happyend is just beginning, and, like ‘The New World’, it’s hard not to get the feeling that with time its legacy will reach far beyond the constraints of the medium its operating in.

There’s no doubt that Happyend has revolution in its veins. Set in a near-future Tokyo, the quietly powerful film explores a society where a fascist government exploits the ever-looming threat of earthquakes to tighten its grip on the Japanese populace. But for all its dystopian edge, the film’s true focus lies in the shifting terrain of a teenage friendship—following best friends Yuta and Kou, whose bond is tested after a prank on their headteacher leads to the installation of a high-tech surveillance system in their school. The growing distance between them is shaped by their opposing political responses to this sudden shift in their ecosystem: Kou’s social consciousness begins to awaken after he befriends a politically engaged peer, while Yuta clings to the comfort of the status quo. The film draws inspiration from Sora’s own experience of developing a social conscience as a young adult, and the gradual impact that awakening had on his friendships. “For me, it was Fukushima,” he says, of his first true brushes with activism. “I started to protest, and started to attend meetings. That was the foundation for me.”

We dialled in with Sora for a conversation on activism, the correlation between pop culture and protesting, and how he wants to inject images of revolution back into the minds of Japan’s youth.

Luke Georgiades: How does it feel for you for wider audiences to finally see this, a year after the film first premiered at Venice?

Neo Sora: I feel like the movie is finally complete. Films are fully complete when they reach the minds of the audience. I’m excited to finally put it down and move on to the next thing.

LG: Were you anticipating the Japanese release of the movie considering the film’s themes?

NS: It was the most nerve wracking for sure. I was keen to see how Chinese and Korean audiences in Japan would see it as well, hoping that I was doing the story justice for them. And hoping that it would irk the people that it was supposed to irk. Which I think it did [laughs]. The other thing that surprised me was how well it did in Korea. It resonated there, probably due to the subject matter, and due to the fact that they recently experienced a popular movement to try and depose the South Korean President, who tried to amass power in the same way that the Prime Minister in Happyend does. So, for them, the timing must have seemed right.

LG: You deconstruct the ins and outs of protesting with real efficiency in the film, to the point where I think young people could benefit from watching Happyend to understand what protesting can achieve and the tactics a government or regime may use to try and dismantle a people’s movement. Was that by design?

NS: The discussions around tactics don’t really change. They’re similar from era to era, and you don’t want to feel like you’re rehashing old arguments. It’s specific also to Japan, compared to France today or Nepal yesterday or Indonesia three days ago. All these places where protests are erupting and people are shooting each other or fist-fighting with the police. It’s not like that anymore in Japan. It was in the 60s and 70s but not anymore. Protesting now is much more defanged due to how harsh the detention is in Japan when you supposedly break the law. In the US, if you’re protesting and they arrest you, you’re usually in jail for a few hours, then you’re released, because they have nothing on you. In Japan, that can go on for 30 days. The only countries in the current nation states that detain people for that long without due process are Japan, Korea and, I think, Israel. It goes to show. So protesting is quite difficult here. It’s harder here for movements to grow into direct action. Also, education in Japan in the last 50 years has removed protesting from the imagination of young people in a big way. With Happyend, I was hoping to inject some of those images back into youth consciousness in Japan.

“Education in Japan in the last 50 years has removed protesting from the imagination of young people in a big way. With Happyend, I was hoping to inject some of those images back into youth consciousness in Japan.”

- Neo Sora

LG: You allow the younger generation a trust in this film that isn’t often given to them by older generations or general media.

NS: For me, it’s the people in their 20s and teens that inspire me the most. And people in their 70s—the older generation who lived through what it was like in 60s Japan. Of course, there were social movements that continued in the interim after the 70s, always holding down the fort, but there was a dip in activism. There was a blip of anti-nuclear movements, but it fizzled out after a while. But it’s coming back a little bit with Palestine now—it’s the younger generation that have really been standing in solidarity. I also don’t want to forget the important work that the people in Okinawa have been doing against the US military bases that have been forced onto Okinawa lands. They’ve been doing sit-ins every single day for the past thousands of days. They’ve been sitting at the gates of these military bases that are under construction and blocking the trucks from moving. So it’s not to say it fizzled out completely. There’s always good work being done.

LG: What did protesting mean to you during your time becoming more politically aware?

NS: It started with the 3-11 Fukushima incident. That’s when I first encountered protests of that scale, especially in Japan. There was so much energy on the streets that I had never felt before in Japan. It opened my eyes, and I took that awakening back to the US, where I was studying at the time. A little after that, in 2011, Occupy Wall Street started, then a little after that the Black Lives Matter movement started. 2007 to the 2020s was like the era of these new political movements. But for me, it was Fukushima. I started to protest, and started to attend meetings. That was the foundation for me.

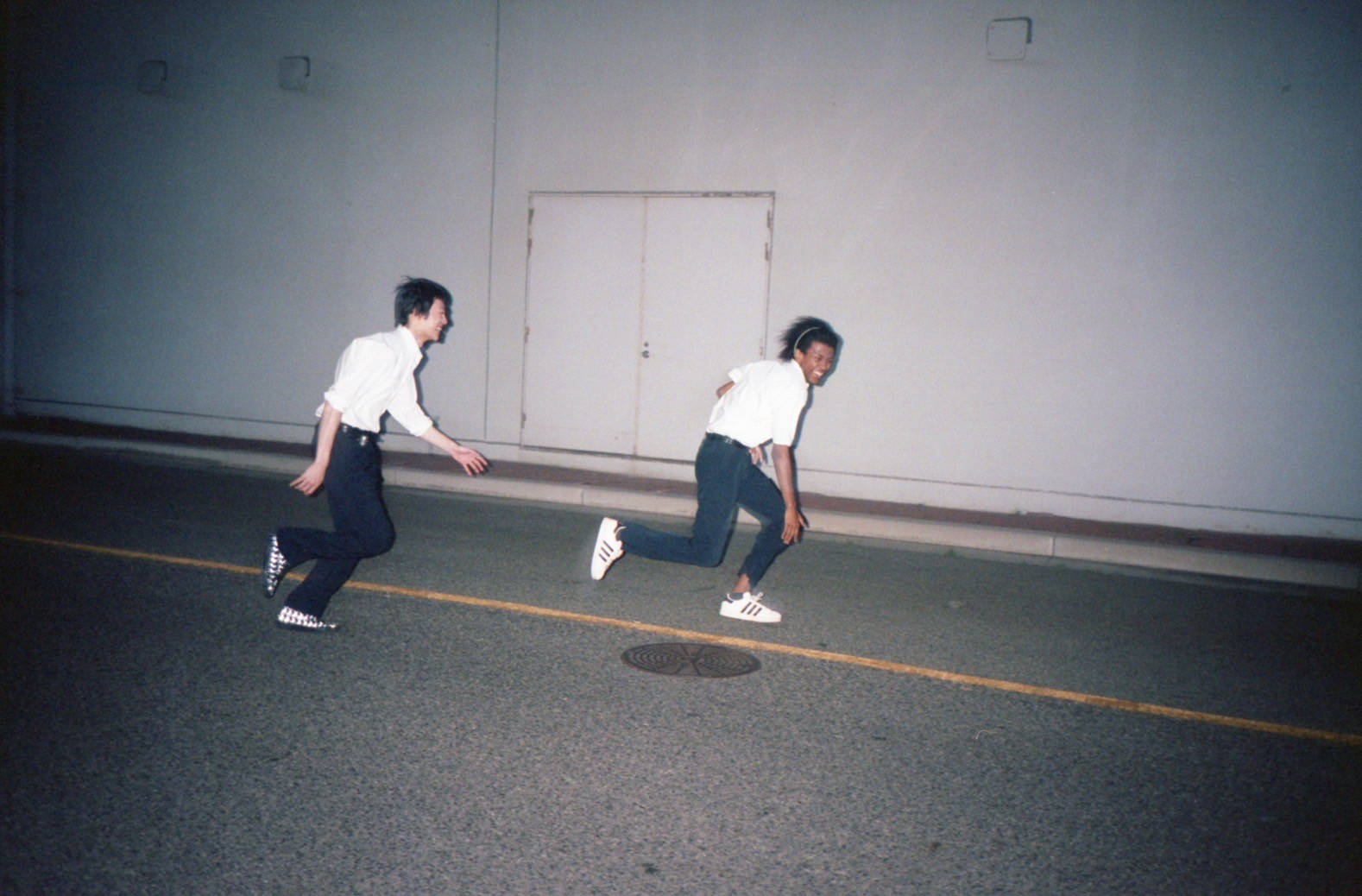

LG: The chemistry between the cast here is like lightning in a bottle. Did you have specific childhood friendships in mind when you were writing the characters?

NS: I drew different characteristics from friendships throughout my life. Bits of myself are inside a lot of different characters here too. I was prepared to rewrite a lot of it for the actors we ended up casting, but I didn’t need to do that at all. Miraculously they had the chemistry we needed. The two protagonists became best friends, to the point where they became roommates after the film. Without that spark, we wouldn’t have had the movie.

LG: Did the narrative change much from when you first conceived it until shooting was underway?

NS: The first memo I found on my iphone was in 2017. Looking back at it, it’s dealing with the same stuff, which is how political differences can divide a friendship, but the way that it plays out did change. There was an element where Kou joined a revolutionary militia [laughs]. They’re all waiting for the earthquake to happen to create an alternative society from the rubble. I wrote that draft, and was kind of reflecting on what I wanted the story to actually be about. The core of the story is the friendship. So over the course of those eight years I shaved off all of the excessive bits. The film Happyend is what was left.

LG: Why was it important for you to set your dystopia in the near-present day?

NS: I was interested in the idea of Brechtian alienation. I simultaneously wanted the film to feel almost like a folk tale, with the near-future aspect, but also as familiar as possible. I structured it so that for long stretches of scenes you would forget that it’s taking place in the future, then suddenly there’s something that reminds you. It’s an economical way of showing the future. If you tread the logic of where Japan might be in the next 40 years, I can easily imagine that it might continue to deteriorate, not only economically, politically, and socially but also physically. The buildings would actually stay the same. They would just get older. Those are the kinds of things that I wanted to reflect in my future world in the film.

LG: Throughout the story music serves, to me, almost as a beacon of hope for certain characters. It’s true for the electronic music that Yuta is obsessed with and the protest music that Kou finds himself being drawn to.

NS: I would highly recommend the ‘eat shit and die’ song. It’s a real song that was banned in the 60s. It’s a satirical song, but if you listen to it, it’s surprisingly relevant to today [laughs]. Same old shit. [Editor’s note: Sora is referring to Okabayashi Nobuyasu’s ‘The Eat Shit Song‘, the lyrics of which feature heavily in Happyend]

I positioned the music as a dichotomy that contrasts Kou, who becomes more political, and Yuta, who essentially engages in escapism. Truthfully, though, it’s not divided in that way. Music is political and vice versa. My favourite example of this is in Korea, where a 2007 K-Pop song called ‘Into The New World’ by the band Girls’ Generation is now the generational protest song. I don’t remember the context, but there was a popular video circulating where 1600 heavily-geared police officers were entering Ewha Womans University, where a peaceful protest was taking place, and all these young women in their 20s formed a human chain and sang this Girls’ Generations song. To this day, it’s still a protest song in Korea. Look at Indonesia happening right now. One of their protest flags is a reference to Luffy from One Piece. In Myanmar, the three-fingers symbol is from Hunger Games. I’ve always loved how pop culture gets adopted into the public consciousness as symbols of protest. There’s a group in Japan called Protest Rave that sets up guerilla raves in the streets as a form of protest.

The idea for Yuta is that the space he’s trying to keep to play music is his way of keeping his friendship group together, and it keeps getting taken away from him. And he keeps essentially engaging in direct action to reclaim those spaces. It’s a very political act—to just do it. So there’s a sub-argument that Yuta is even more radical than Kou, whether intentional or not, because he’s engaging in direct action.

“Music is political…My favourite example of this is in Korea, where a 2007 K-Pop song called ‘Into The New World’ by the band Girls’ Generation is now the generational protest song. I don’t remember the context, but there was a popular video circulating where 1600 heavily-geared police officers were entering Ewha Womans University, where a peaceful protest was taking place, and all these young women in their 20s formed a human chain and sang this Girls’ Generations song…I’ve always loved how pop culture gets adopted into the public consciousness as symbols of protest.”

- Neo Sora

LG: What music were you turning to as a young activist to provide inspiration for political action?

NS: I don’t know if it was happening as a cause and effect thing, but during my political awakening at university I was simultaneously getting involved with the techno scene, but I noticed that a lot of the clubs I was frequenting, especially in Brooklyn, were engaging in experiments to create safer spaces for all sorts of people with different identities and backgrounds. That kind of practicing of those theories resulting in a change of physical space was quite eye-opening. I took that to heart. Now those practices have made their way to protest-culture in Japan, especially young people who are setting up protests that create a space that encourages as many different people to join in. The idea of a safe space obviously didn’t originate in clubs, but they’re the perfect place to practise creating safe spaces.

LG: If you had to pair this movie with another for a double feature, what movie would you choose and why?

NS: I have different answers depending on the mood I’m in. Design for Living by Ersnt Lubitsch. It’s a love triangle film, and Happyend is a love triangle film, but of friendship between Yuta, Kou and Sumi. I love Jean Vigo’s rebellious Zero for Conduct. Of course, I love the Taiwanese New Wave films. The Boys from Fengkuei by Hou Hsiao-hsien. Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day. One film I don’t talk a lot about which I want to mention is the Nobuhiko Obayashi film Bound for the Fields, the Mountains and the Seacoast. There’s a weird collapsing of time in that film. One of the characters, an elementary school kid, is named after well-known anarchist Ōsugi Sakae. He’s just named that [laughs]. It’s also about students coming together to depose the system. It’s a great film. Those are the touchstones.

LG: I know from our last conversation about Opus that you have an interest in the phenomena of time. I’m curious as to how that interest manifested here?

NS: Essentially what I’m doing in Happyend is folding four different times into one film. I’m making the film from the present, but I’m strongly referencing 1923, which is when the great Kanto earthquake happened in Japan and resulted in the massacre of Koreans. I’m taking that incident and using it as the foundation of the analysis of Japanese colonial history in the film. Then I’m folding in the near-future aspect, which I use as an excuse to also analyse and think through the logical contradictions of Japanese society. But emotionally what I’m really doing is making a film that essentially feels like a flashback of Yuta and Kou’s memories if they were to get together in their 30s and look back on their friendship. I wanted the perspective with which we’re telling the story, the camera placements, the affect of the music, to express a reflective, emotional distance to what we’re seeing on screen. I wanted to layer those four times on top of each other simultaneously.