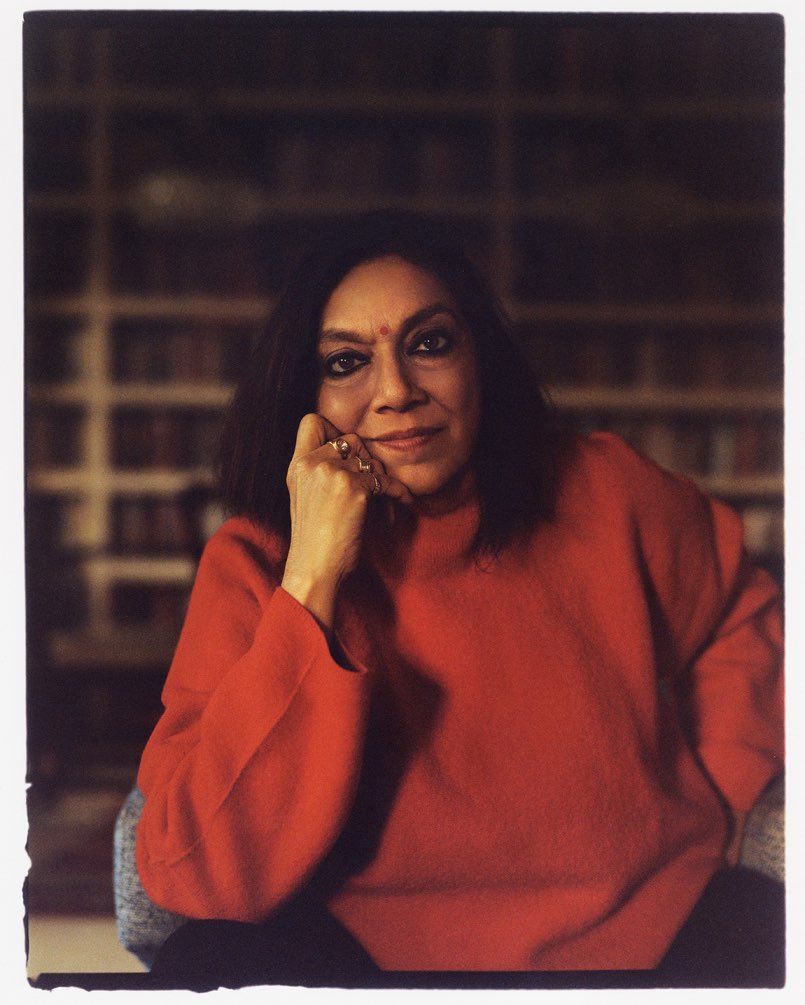

A Rabbit’s Foot Creative Director Fatima Khan spoke to the trailblazing Indian-American filmmaker Mira Nair about her ever-evolving cinematic legacy which includes Mississippi Masala (1991) and Vanity Fair (2004), the power of moral imagination, and what she really thinks about the Mayor of New York City. Portrait by Sophie Hur.

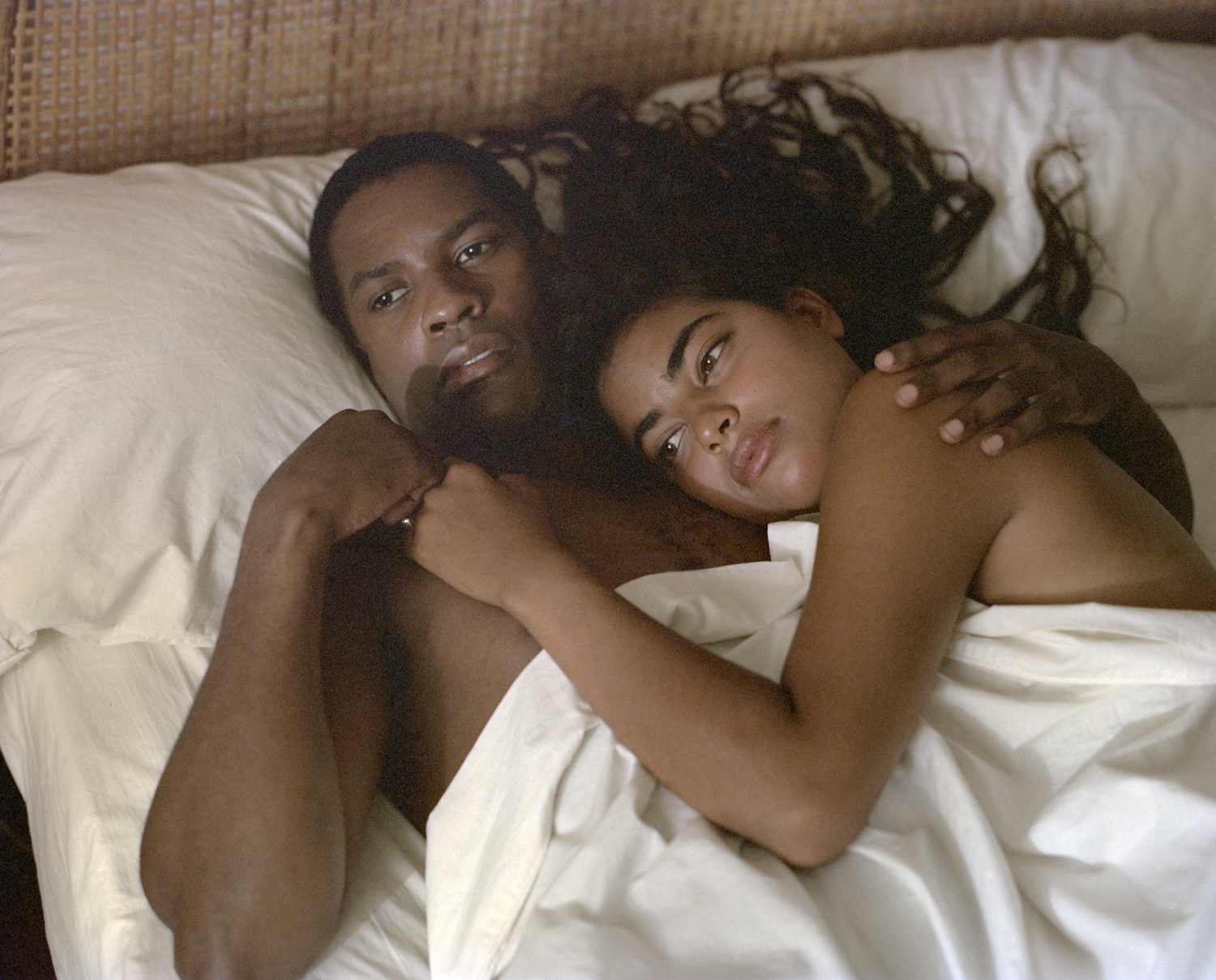

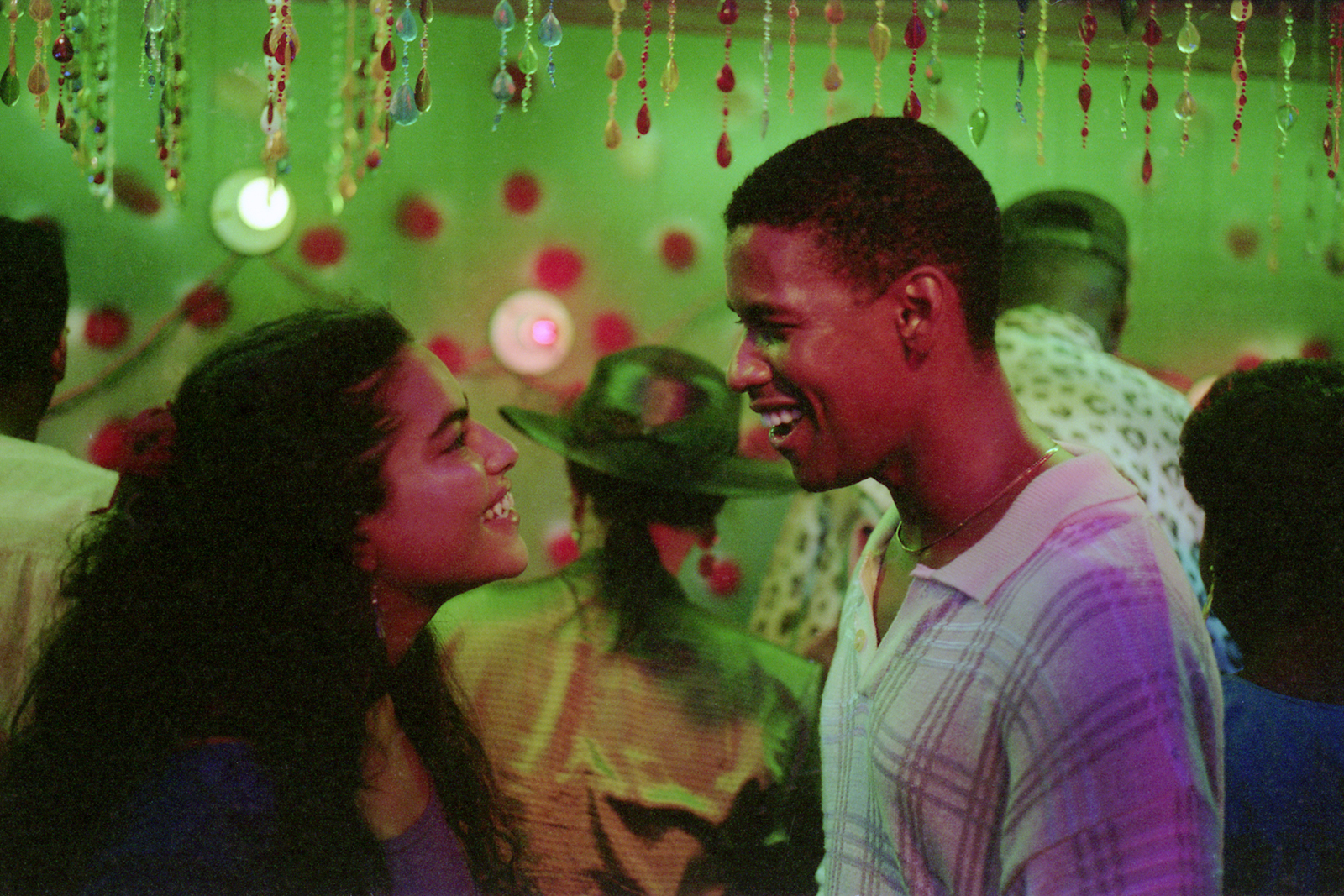

When we meet Mira Nair over an afternoon Zoom call, the acclaimed filmmaker is preparing for transit, getting ready for the long-haul flight from New Delhi, India, back to her home in Manhattan, New York City. It’s a fitting moment to speak with the director, whose colourful films so often reflect—delicately, politically, and profoundly—both her dual Indian and American identities. Nair, a trailblazer of independent cinema, has always had her fair share of devotees and die-hards, but, as of late, her legend has grown significantly. For one, cult home-video distribution company Criterion has taken it upon itself to give Nair her flowers: last year, it released a gorgeous 4K restoration of her masterful Mississippi Masala (1991), a vibrant, intimate, interracial love story set in the rural South and starring Denzel Washington and Sarita Choudhury (perhaps, two of the most beautiful human beings alive at the time). Now the company is preparing to release Salaam Bombay! (1988), Nair’s electrifying Bombay-set fiction debut that won her nominations at the Oscars, Golden Globes, and BAFTAs.

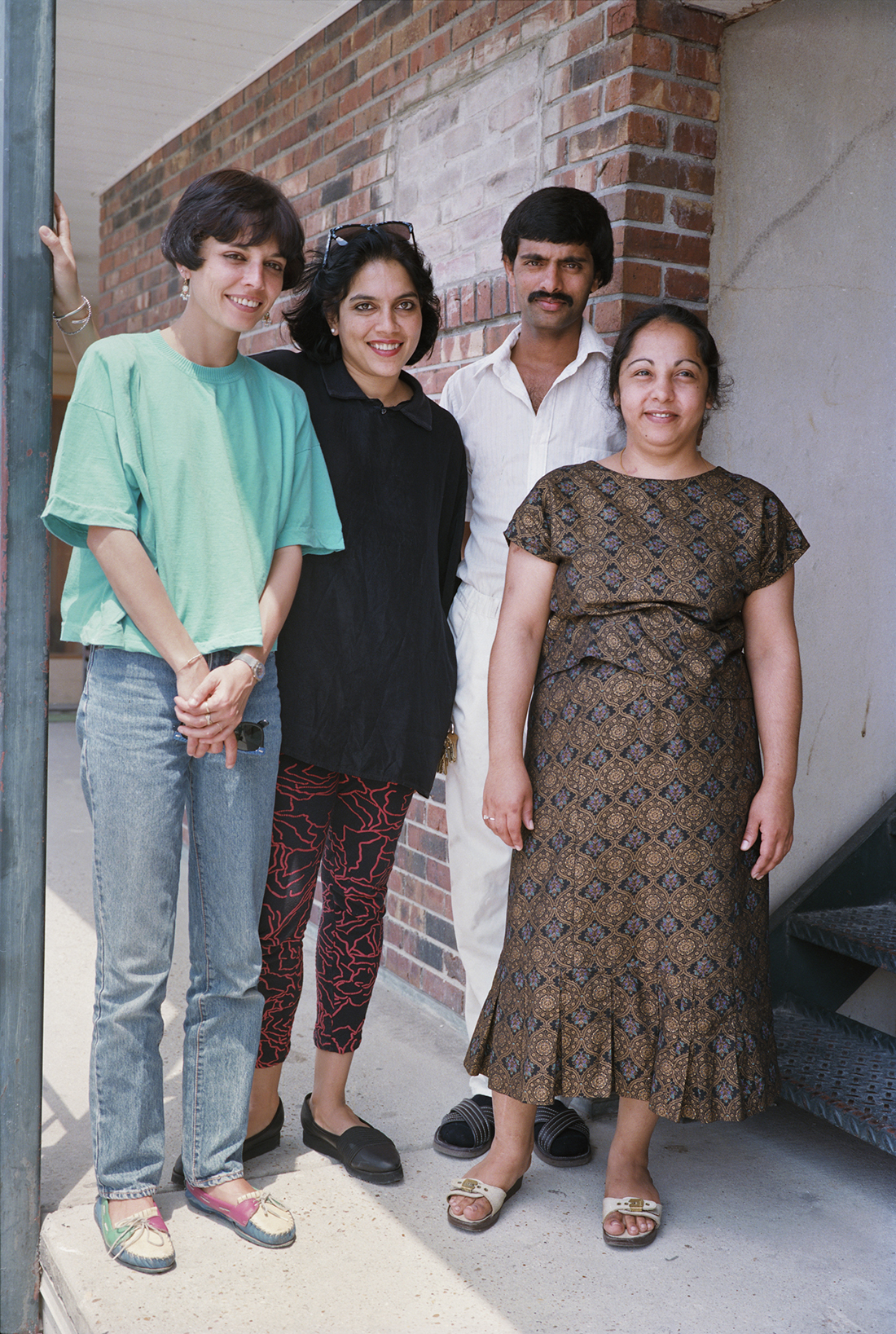

Two weeks after our interview, we get a chance to take a portrait of Nair in her Manhattan home, and the energy in New York City is even more exhilarating than usual. A few days earlier, Nair’s son Zohran Mamdani had been elected the new Mayor—he’ll be sworn in in January—and the concrete jungle feels alive and hungry: a city ready for a new dawn. Naturally, Nair is over the moon. “I am moved by how resolutely himself he is,” she had told us before his historic win. “He only does what he believes in. That’s brave—because it’s not ambition-driven. And it’s the same mantra I teach at Maisha Film Lab, my free film school in East Africa: If we don’t tell our own stories, no one else will. That’s what he’s doing, too—claiming space, saying, ‘We exist, we belong, we deserve dignity’.”

You’ve journeyed from Orissa to Delhi to Harvard—at what point did storytelling first begin to take hold of you?

Each of those places trained me in different ways, but Orissa was the beginning. My parents were helping build the new capital in the 1950s, so I grew up in Bhubaneswar—this new India rising in the middle of ancient India, surrounded by temples and fields, no movie theatre in sight, and an airport only when I was eight. It was almost rural, but full of stories—retired civil servants talking about man-eating tigers, dancers rehearsing Odissi in overgrown shrines, and the daily closeness between those who served and those who were served. That inequality fascinated me early on. As the youngest of three, my brothers were my first audience—I had to earn the right to tell a story. I was industrious, always asking: am I a musician? A painter? But I knew I could write. Books were my world. In those days India and Russia were intertwined, and we bought Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov for two rupees—odd pink paperbacks that shaped my imagination. I was always searching for Indian writers, trying to meet someone who had written their own story. It was a strange childhood pursuit in postcolonial India, when we were raised on English and Russian literature but rarely our own.

At Harvard, you shifted from theatre to photography to documentary. Was there one moment that made filmmaking feel urgent?

Harvard was my first real training in cinema. Growing up in the boondocks, I hadn’t even seen Satyajit Ray until I was 20. I saw the Apu Trilogy for the first time in Science Center B—it was a revelation. I studied cinéma vérité, the “cinema of truth,” with Ricky Leacock, who helped pioneer handheld documentary with DA Pennebaker. We learned to see life unfiltered, as it is. At the same time, I was discovering global cinema—Buñuel, Makavejev, Jean Rouch, and the Japanese masters: Mizoguchi, Ozu, Kurosawa. I was drawn to their lyricism and surrealism; it resonated with India’s oral and mythological traditions, the yatra plays of my childhood that could conjure whole worlds from nothing. Films like The Battle of Algiers (1966) hit me hard. They showed that you could make high-octane poetry out of politics. That idealism possessed me early on—the question, can art change the world? Could what we make—film, theatre, music—address the inequities I grew up surrounded by? Even in my small town, injustice was normalised: there were those who served and those who were served. That became the central tension of my storytelling.

You’ve spoken about feeling in-between communities—brown, Black, white, Indian in the West. How do you draw from that, and do you think we’re in a more polarised moment of identity politics now?

When I began, that in-between space was lonelier. The fluidity between communities wasn’t defined, and there weren’t many examples of hybridity. Coming to Harvard in the late 1970s was exhilarating—suddenly, I was meeting the world. It was collaborative and porous, but there was also no vocabulary yet for what we now call multiplicity.

Today, I see younger generations—like my son—embodying that fluidity with ease. They don’t have the loneliness we did. And America itself felt more open then than it does now. My husband once told a story of taking a Greyhound across Arizona: he asked the driver if they could stop so he could pray. The driver announced, “Folks, we’ve got a Muslim here who wants to pray—what do you say?” Every hand went up in agreement, and the bus stopped so he could do his namaz. That would never happen today. Now you’d have ICE called on you. We’ve regressed. When I started making films, I didn’t even call it art. It was lonely work because I didn’t know who I was speaking to. There’s a Hindi saying: Dhobi ka kutta na ghar ka na ghaat ka—the washerman’s dog belongs neither to home nor the street, but is at home everywhere. That was me.

If you were Indian in America then, you wanted to see only the “good” parts of India—you didn’t want Salaam Bombay! or Mississippi Masala. I was attacked for showing a Black man and a brown woman in love. Indian men would confront me on the street in New York, furious at what they saw as misrepresentation. But when Mississippi Masala opened at the Curzon in London, I saw lines around the block—mixed couples everywhere. It was the first time I felt my work had found its audience. It was a lonelier time, but also freer in some ways. Today, films are still commissioned and financed mostly by those who look like the work. We still have to fight for our stories—not for “representation,” I dislike that word, it’s too dry—but to reveal the half of the world that remains unseen.

The restoration of Mississippi Masala has introduced it to a new generation. When you revisited the film, did it feel newly resonant?

What amazed me was that it didn’t feel dated at all. In fact, it felt braver now than when we made it. I don’t think we could make that film today— people would censor themselves 10 times over. Mississippi Masala used humour, thanks to Sooni Taraporevala’s writing, to reveal the ignorance between communities—the ways Black, brown, and white people coexisted yet barely knew each other. The film grew from my own experience of the perceived hierarchy of colour. As a student, I moved between Black and white communities and saw those invisible lines. That’s what I wanted to explore. Later, I found the story of the Ugandan Indians expelled by Idi Amin—people who thought of Africa as home but were told they didn’t belong. I wanted to explore that question: what is home now? The African American who’s never known Africa, the Indian who’s never known India—we’re all searching for home. I still don’t think there’s been another film quite like it.

Still from Mississippi Masala (1991).

When you were researching in Mississippi, living in motels and observing those communities, did that change your view on love, race, or displacement?

Being in the South for that long was revelatory and painful. The culture was rich—the Delta blues, the spirituality—but the economy was ravaged. You could feel the marginalisation of the Black community in their own homeland. There was warmth too, but also direct hostility. In certain bars, you simply weren’t welcome. We felt it even during filming. Denzel Washington’s contract required a separate mansion for him, but he refused, saying, “I’m staying where everyone else is.” We both stayed in the same modest inn, because the idea of segregation—of “your own place, boy”—was still palpable. It was abject at times. Yet amid that, there was joy, music, connection. That duality defined the experience.

It’s fascinating that you faced that hostility and still made something so tender. My father, who migrated to the UK, used to say that overt racism was painful but at least you knew where you stood—whereas today it’s all coded, invisible lines.

Exactly. The coded dance is much harder than the direct insult.

Both of your leads in Mississippi Masala carry so much emotional and historical weight. Were you looking for that when you were casting, to avoid sentimentality?

No, no. You don’t set out like that. The Bhagavad Gita says, beware the fruits of action. You can’t begin a film thinking, “I’m going to make something eternal.” You have to be in the moment. Coming from cinéma vérité, and from seeing the extraordinariness of ordinary life, I learned humility–how to capture people, how to draw truth from them. For Mina, I wanted someone intelligent and unvain—not concerned with how she looked, but with a kind of fierce inwardness. I found Sarita in a Face magazine spread. I was drawn to her immediately: her beauty on her own terms, her lack of vanity. She wasn’t even a trained actor, just a film student, but exactly what I hoped for. With Denzel, he wasn’t yet a star—maybe two or three films in. I’d seen him in a small British indie, For Queen and Country (1988), and thought he was extraordinary. We actually wrote the part with him in mind, hoping he’d say yes. Unknown to me, he had seen and loved Salaam Bombay!—that’s why he took the meeting.

He told me later he’d never been offered a “Black–brown” film before, never been asked to act opposite an Asian woman, and that intrigued him. Even then, the studios wanted me to “make room for a white protagonist.” I joked, “All the waiters in the film will be white, don’t worry,” and they laughed—and then showed me the door. That’s why I’ve always said the price of freedom is a stringent budget. You can only make what you want to make when you work outside the mainstream.

The chemistry between Sarita and Denzel is remarkable. Especially that phone scene—it’s so full of feeling without being explicit. How did you build that emotionally?

That scene came from my own life. I had fallen deeply in love—my husband now, though he wasn’t then—and we were living continents apart. This was before email, before any instant connection. The phone was everything. That longing—emotional, spiritual, physical—I knew it, I wanted to capture it.

I used to tell Denzel, “I’m making this film in a stupor of love.” I said, “You’re giving me the dutiful son, the good man, but I need to feel your knees go weak.” The only way was through vulnerability—letting himself be seen. It was a tough conversation to have with a great actor when I was only 30-something, but you have to fight for instinct.

Eventually, I talked marketing—told him audiences would feel it—and that clicked. When the film came out, people screamed at the screen in New York. It was interactive cinema. And interestingly, it’s the only romantic role he’s ever done.

Three Girls, 1935. Oil on canvas. By Amrita Sher-Gil.

I’m now making a film about Amrita Sher-Gil—the Indo-Hungarian painter, our subcontinent’s Frida Kahlo, a pioneer of Indian modernism. It’s taken me four years to get it greenlit, even with my track record. People don’t immediately see why it matters. But her story possesses me—a woman living on her own terms, a century ago, creating extraordinary work between East and West.

You’ve had major successes with Salaam Bombay!, Mississippi Masala, Monsoon Wedding. With all those opportunities, what’s helped you hold your own voice instead of following the Hollywood system?

My roots. I’m at home in many places, but my stories have to come from within. I always ask myself: Can anyone else make this film? If the answer is yes, then they should make it. I only take on stories that I alone can tell. That’s why I made Vanity Fair–it wasn’t about India, but I saw something in Thackeray’s point of view about empire and hypocrisy that resonated. If I can bring a unique angle, I’ll do it. Otherwise, life is short—I want to tell the stories that only I can tell.

That’s your North Star in a way.

I suppose so. I’m now making a film about Amrita Sher-Gil—the Indo-Hungarian painter, our subcontinent’s Frida Kahlo, a pioneer of Indian modernism. It’s taken me four years to get it greenlit, even with my track record. People don’t immediately see why it matters. But her story possesses me—a woman living on her own terms, a century ago, creating extraordinary work between East and West.

Emily Watson plays her mother—a bipolar Hungarian opera singer—and I’ve discovered a young actress for Amrita. It’s a love story, a taboo marriage, a life between worlds. When something grips me like that, I can’t chase anything more commercial. I’m a long-distance runner.

Working across continents as a woman of colour, you’ve built a career in spaces that weren’t made to include you. What kinds of resistance have you had to navigate—and what forms of solidarity have sustained you along the way?

Resistance is constant. You have to have the skin of an elephant and the heart of a poet. Rejection is part of life—you almost have to embrace it. I never saw it as defeat, but as fuel.

What helped me early on was what I call “the foolish confidence of the Ivy League.” Harvard gave me that. You stop being intimidated by power. You learn to ask—to reach out. What’s the worst that can happen? They say no. That’s how I got to Denzel, to studios, to financiers. And yes, there were people who supported me in unexpected ways—grants, donors, friends who helped me finish Salaam Bombay! when I was short of money. It wasn’t crowdfunding back then; it was literally fundraisers in people’s homes.

The bigger resistance was invisibility. Never seeing ourselves on screen. Never seeing people like me—or you—in stories. I used to ask as a child, why are the heroes always Peter, Paul and Mary? What about Fatima, Mira, Rajesh? Monsoon Wedding was just my family table, really. We had Cuban cigars in the house, but no one thought India could be cosmopolitan. That’s what I wanted to show: the life we actually live, the stories we don’t see.

You’ve spoken a lot about courage and self-belief. I can’t help but think of your son, Zohran— it feels like he’s inherited that same bravery in his own work.

[Zohran’s] grown up with those values, yes—seeing the world’s beauty and its brutality. He worked on Queen of Katwe (2016) from start to finish, finding many of the kids in the film. He’s a natural storyteller, very intuitive. People think I help with his campaign videos—I don’t. He already has it. It’s in the editing, in how he reads people, how he removes confusion. His empathy and connection are his own. I don’t really think in terms of pride, but I am moved by how resolutely himself he is. He only does what he believes in. That’s brave— because it’s not ambition-driven. And it’s the same mantra I teach at Maisha Film Lab, my free film school in East Africa: If we don’t tell our own stories, no one else will. That’s what he’s doing, too–claiming space, saying: we exist, we belong, we deserve dignity.

How do you look at the idea of legacy?

I have always insisted on excellence in craft. When I began, we had to fight to simply to be seen, to be heard, to convince the world our stories mattered. That they were niche but human. That struggle taught us patience, resilience, and the value of rigour. Today, I hope the younger generation uses the access and visibility they have—and we didn’t—and couple it with discipline and craft. The point is, not just to speak, but to speak well. To make work that will last. It’s not enough to simply be us now—we must still deserve to be heard.

Mira Nair, Mahmood Mamdani, and Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani on election night, 2025. By Sinna Nasseri.

He’s a natural storyteller, very intuitive. People think I help with his campaign videos—I don’t. He already has it. It’s in the editing, in how he reads people, how he removes confusion. His empathy and connection are his own. I don’t really think in terms of pride, but I am moved by how resolutely himself he is.

Mira Nair on her son, Zohran Mamdani

Your films have always asked us to see one another with empathy, across borders and hierarchies. In a moment outrage so often replaces curiosity, what does moral imagination mean to you now—both as an artist and as a citizen?

Moral imagination is everything. How you see reveals who you are. I’ve always straddled worlds, and my work comes from the tension— and the beauty—of that in-between. To live in multiple worlds and belong fully to neither. My films have always tried to make that space visible; not through speeches or slogans, but through the intimate language of family, memory, and longing.

Today, when outrage so often replaces curiosity, moral imagination is about staying open. To see another person—without reducing them—is the deepest act of creativity. I see this in my son and his generation. How they hold multiplicities with more ease. How they demand justice without conviction but also understand complexity. That gives me hope!

Foot Note

As she tells A Rabbit’s Foot, Mira Nair’s next film is about the Indo-Hungarian painter Amrita Sher-Gil (1913–1941), often referred to as the Picasso or Frida Kahlo of India. Born in Budapest to an aristocratic Sikh father and a Hungarian mother, she studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris where she was taught the work of Gauguin and the post-Impressionists. In 1934, she returned to India, combining European aesthetics with a bright Indian palette in paintings of rural life that focus on young women and girls. Sher-Gil died tragically young aged 28, but her ambitions about founding an Indian modernism are preserved in the extensive letters she left behind: “I can only paint in India. Europe belongs to the past.”