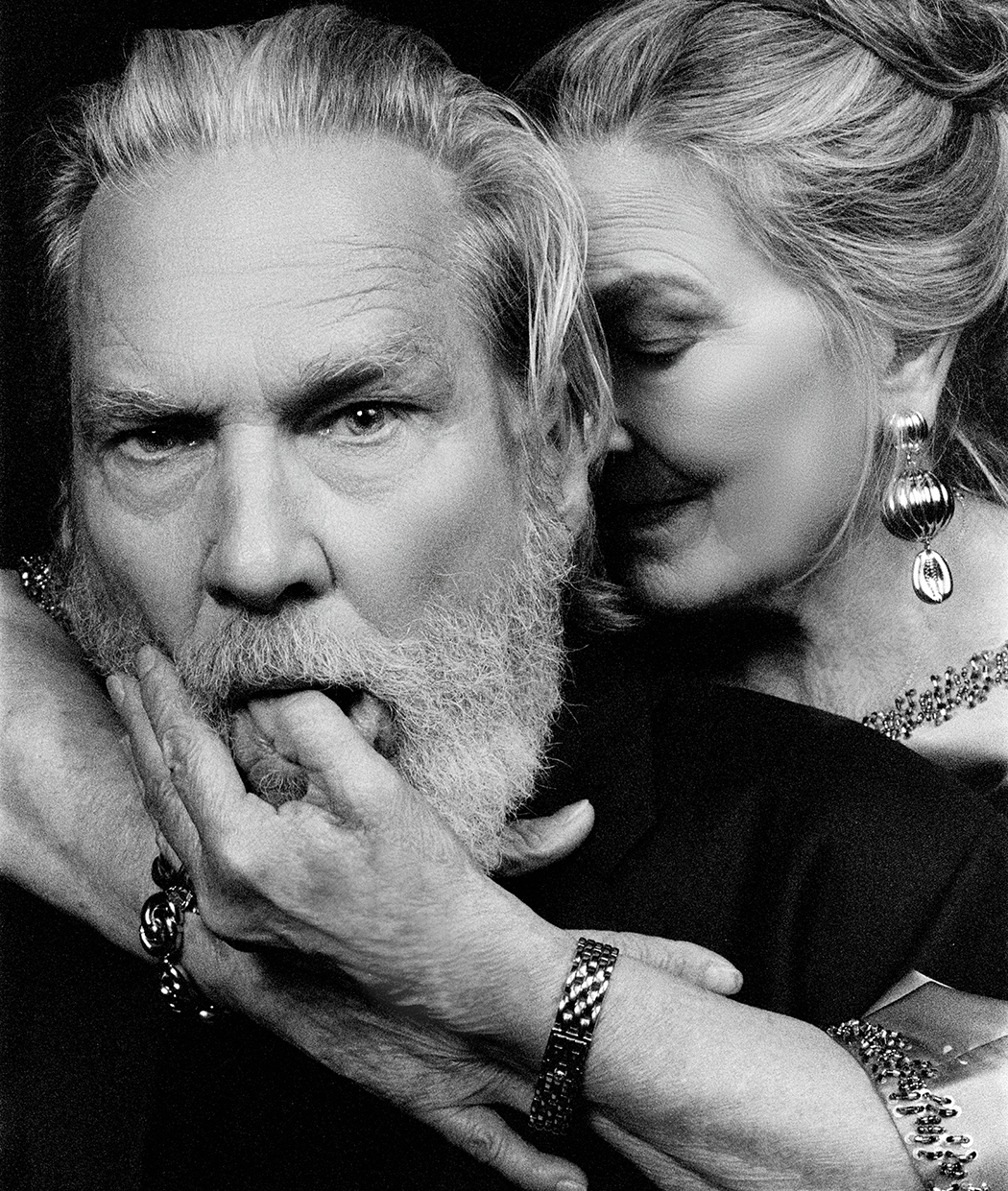

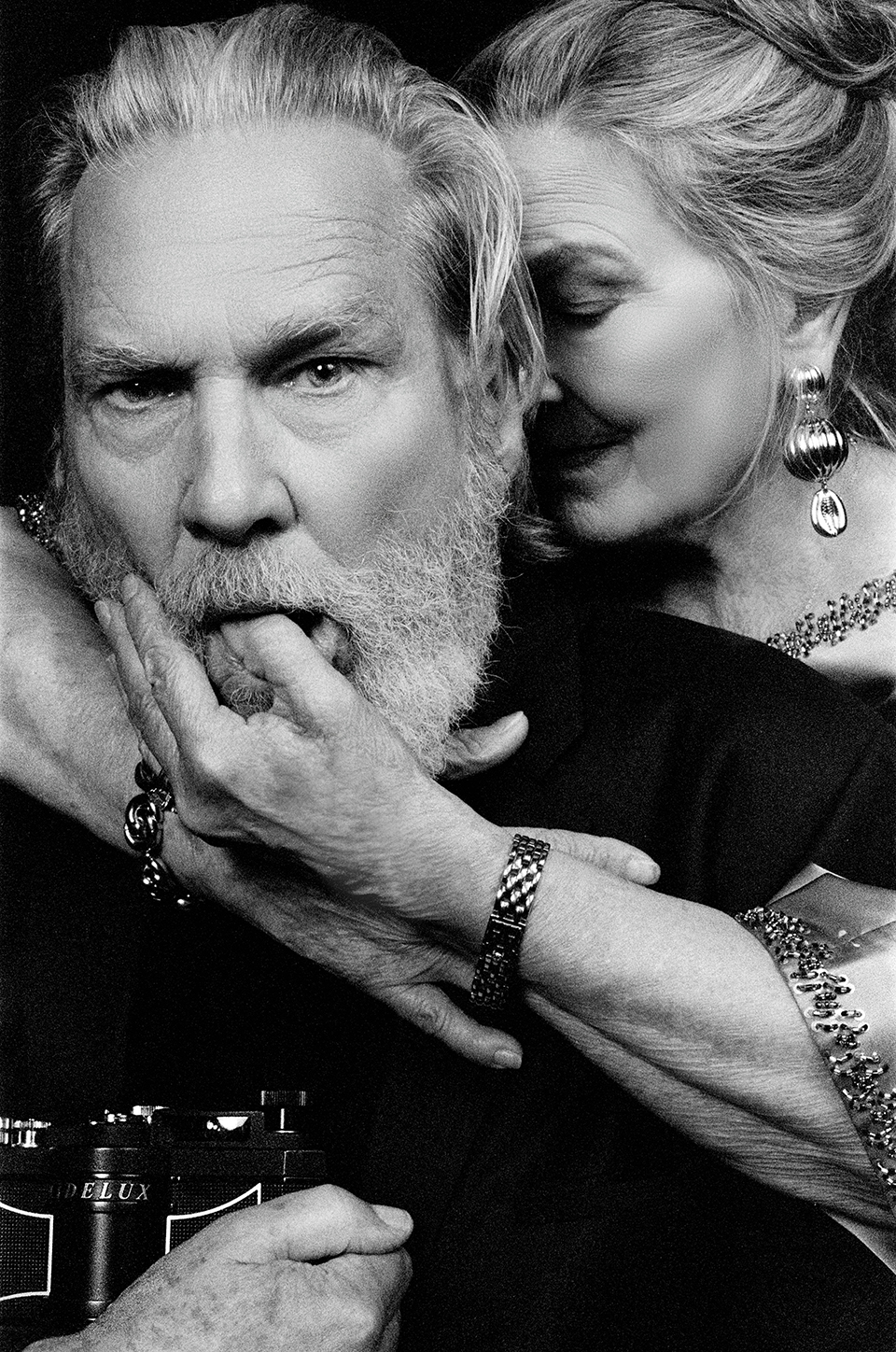

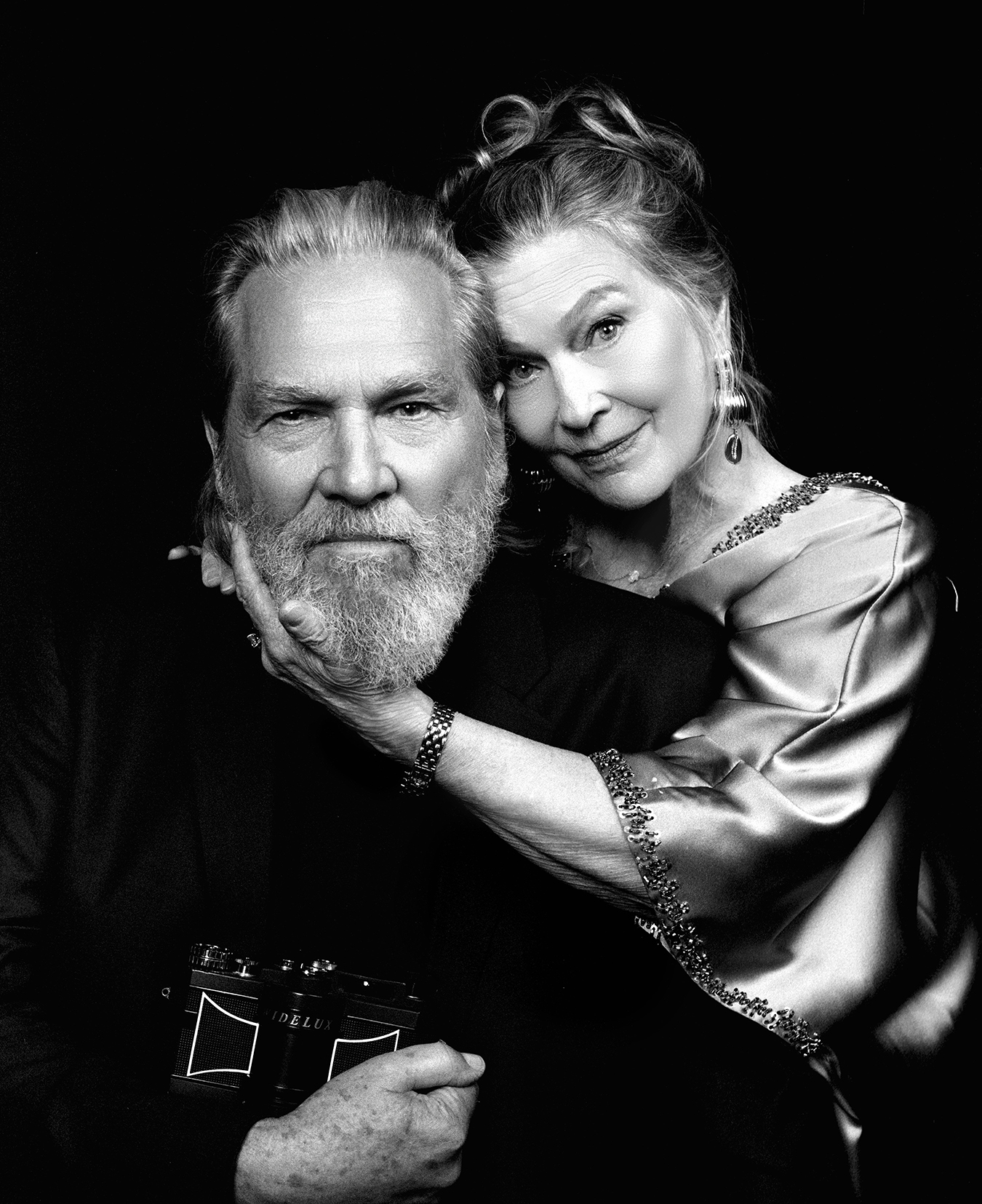

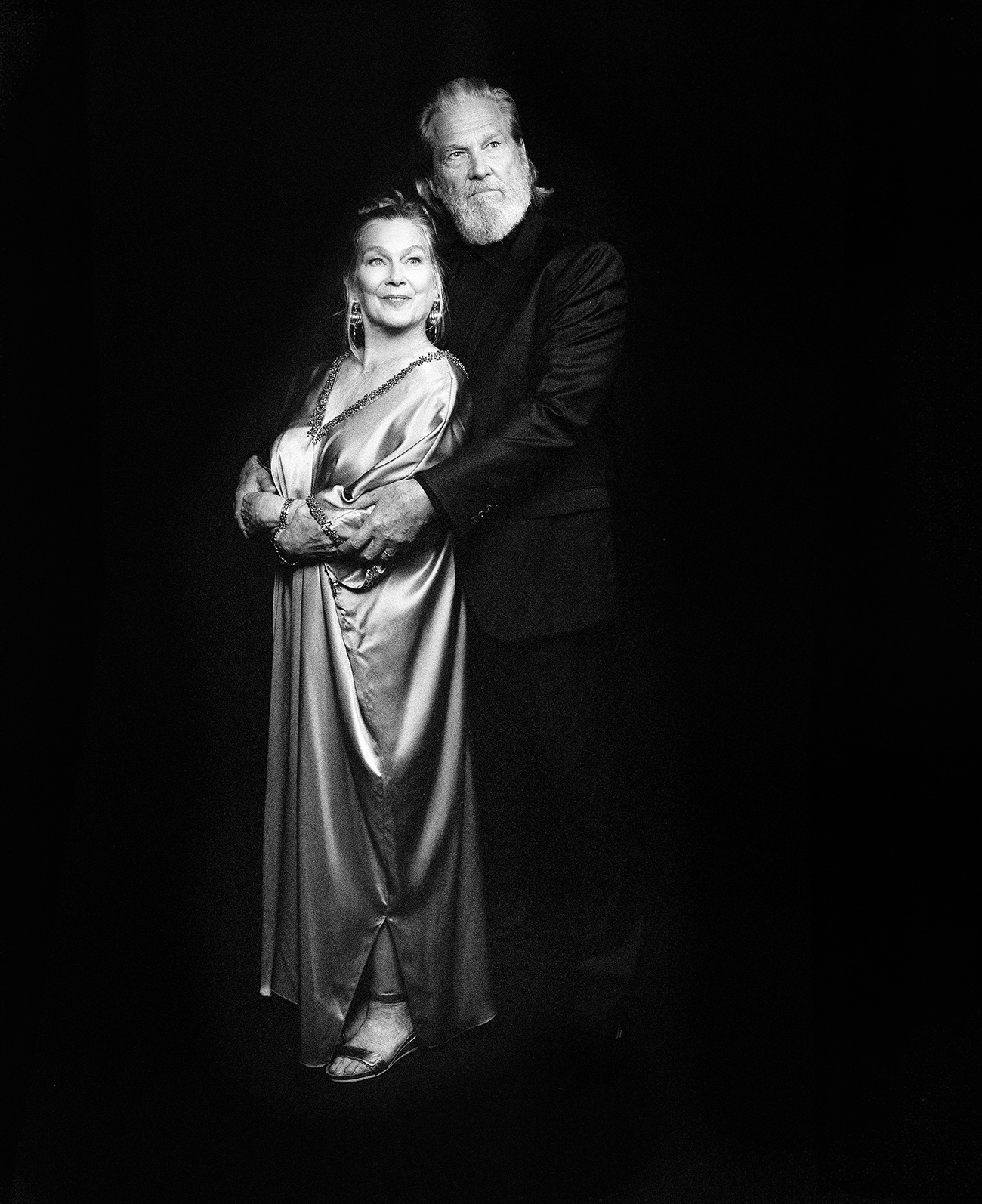

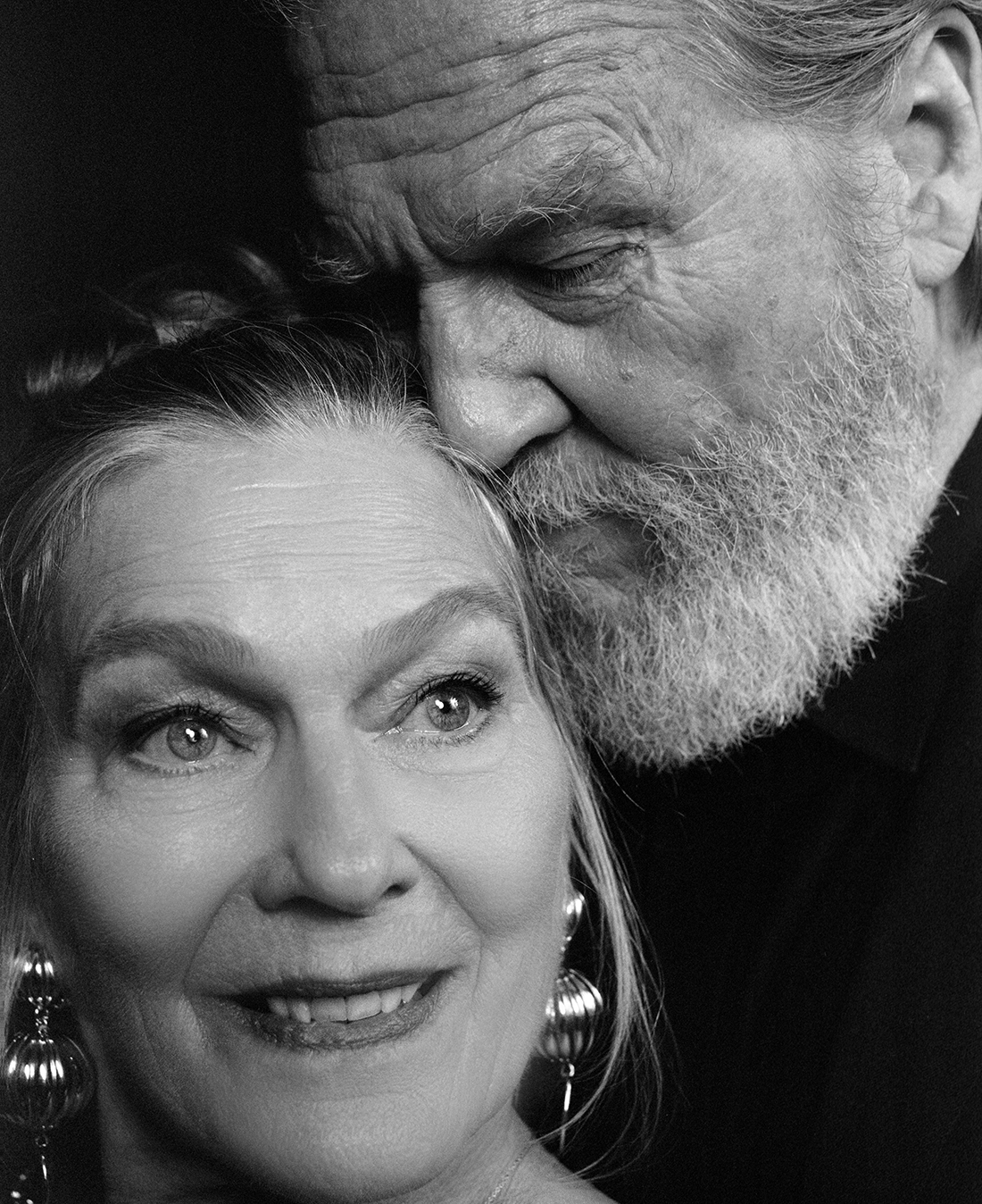

A sneak peek at our time with The Bridges ahead of their special screening of Heaven’s Gate on November 15th—starting with an exclusive conversation with Susan Bridges and a teaser for our short film starring the two.

There’s a curious thing about Heaven’s Gate: for all its reputation as one of Hollywood’s grandest catastrophes, time has looked kindly on its legacy.

Michael Cimino’s breathtaking frontier epic didn’t always carry the title of one of the great American films of all time (though it certainly qualifies now). When it was first released in 1980, the response from critics and audiences alike was brutal. The film, careening out of an infamously troubled production, was universally panned and became one of Hollywood’s most notorious flops.

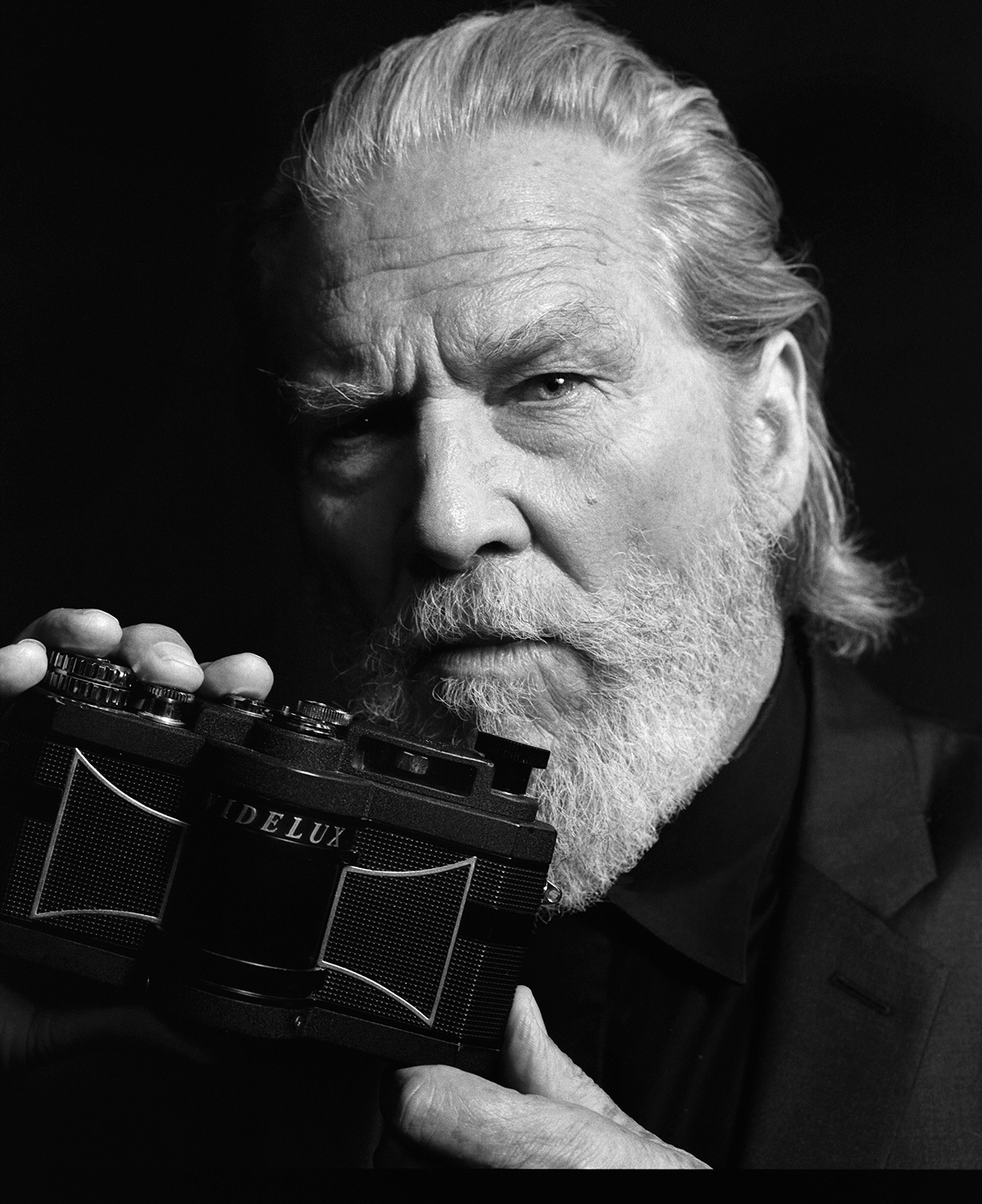

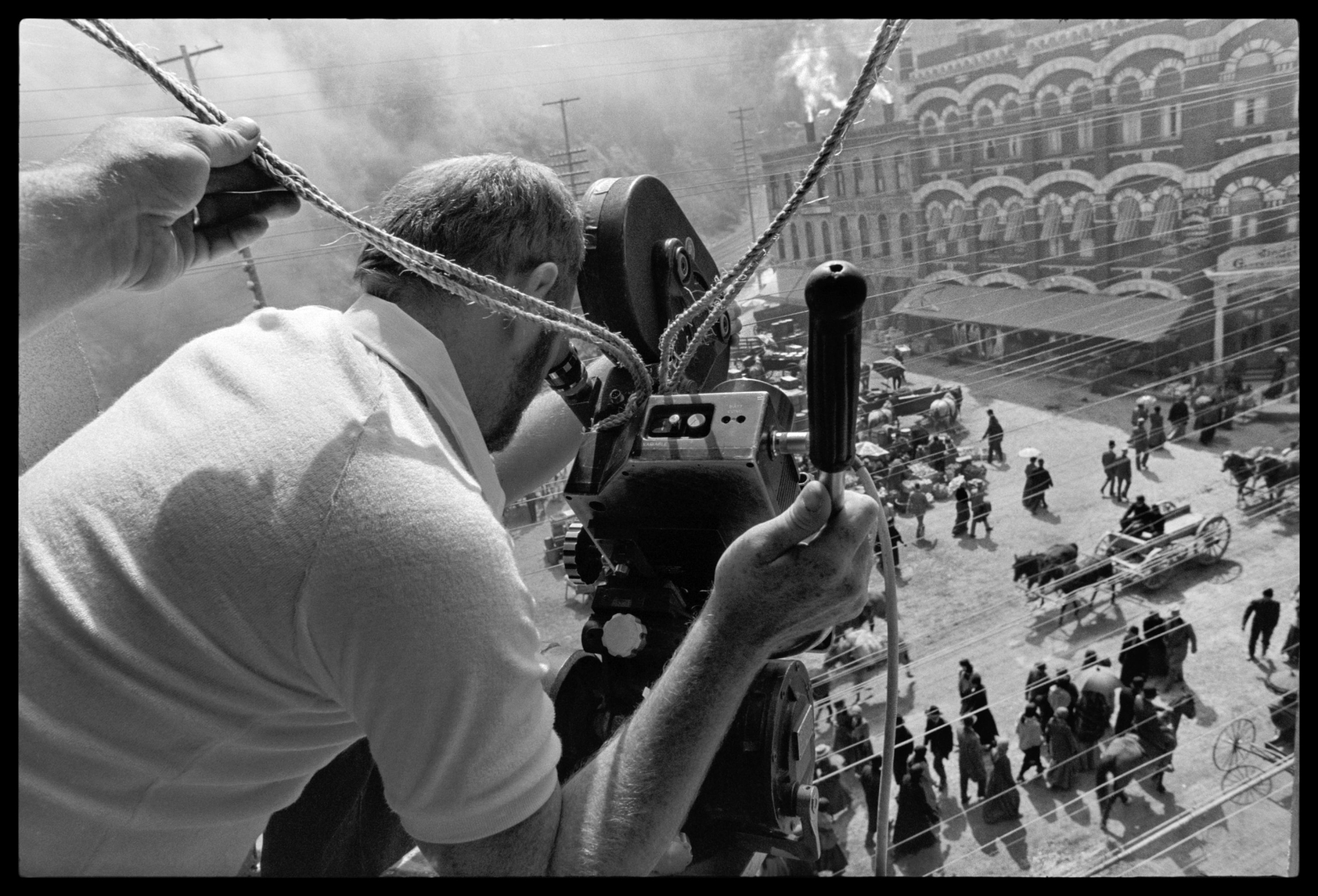

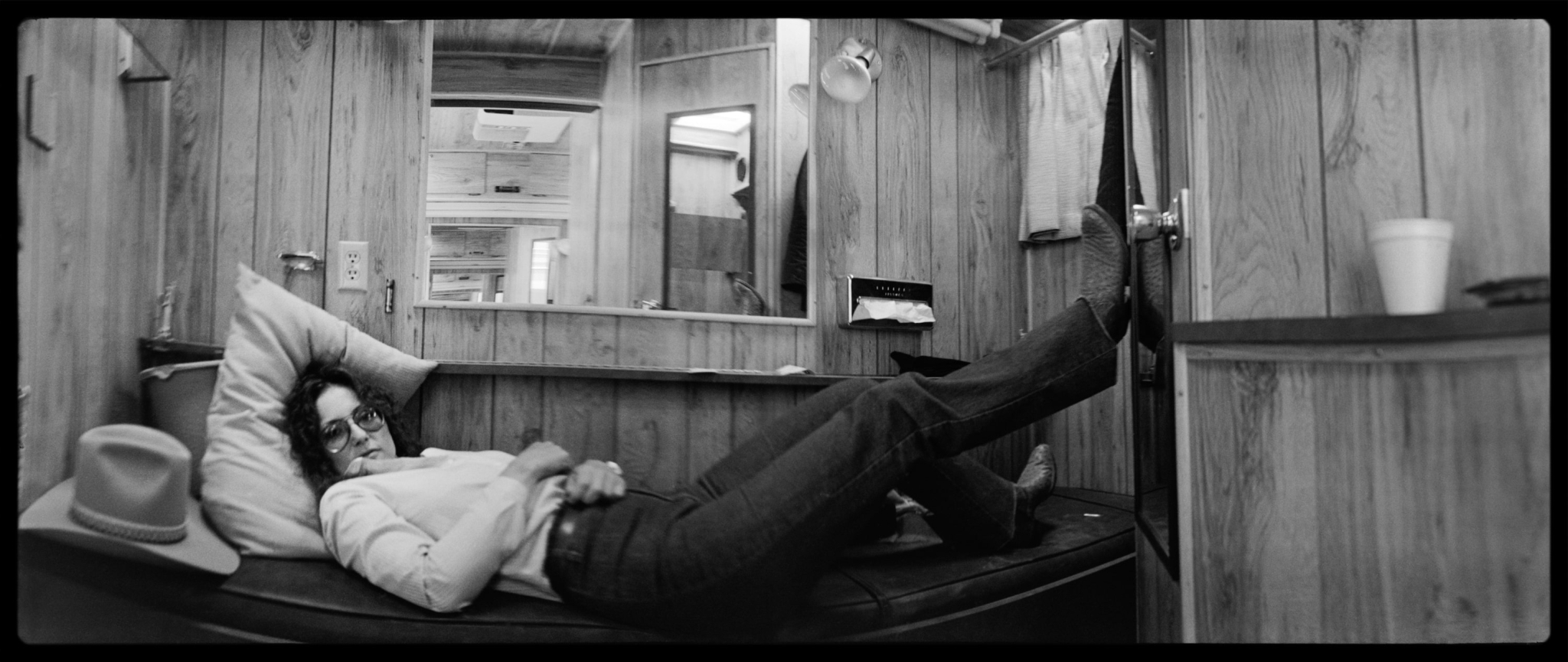

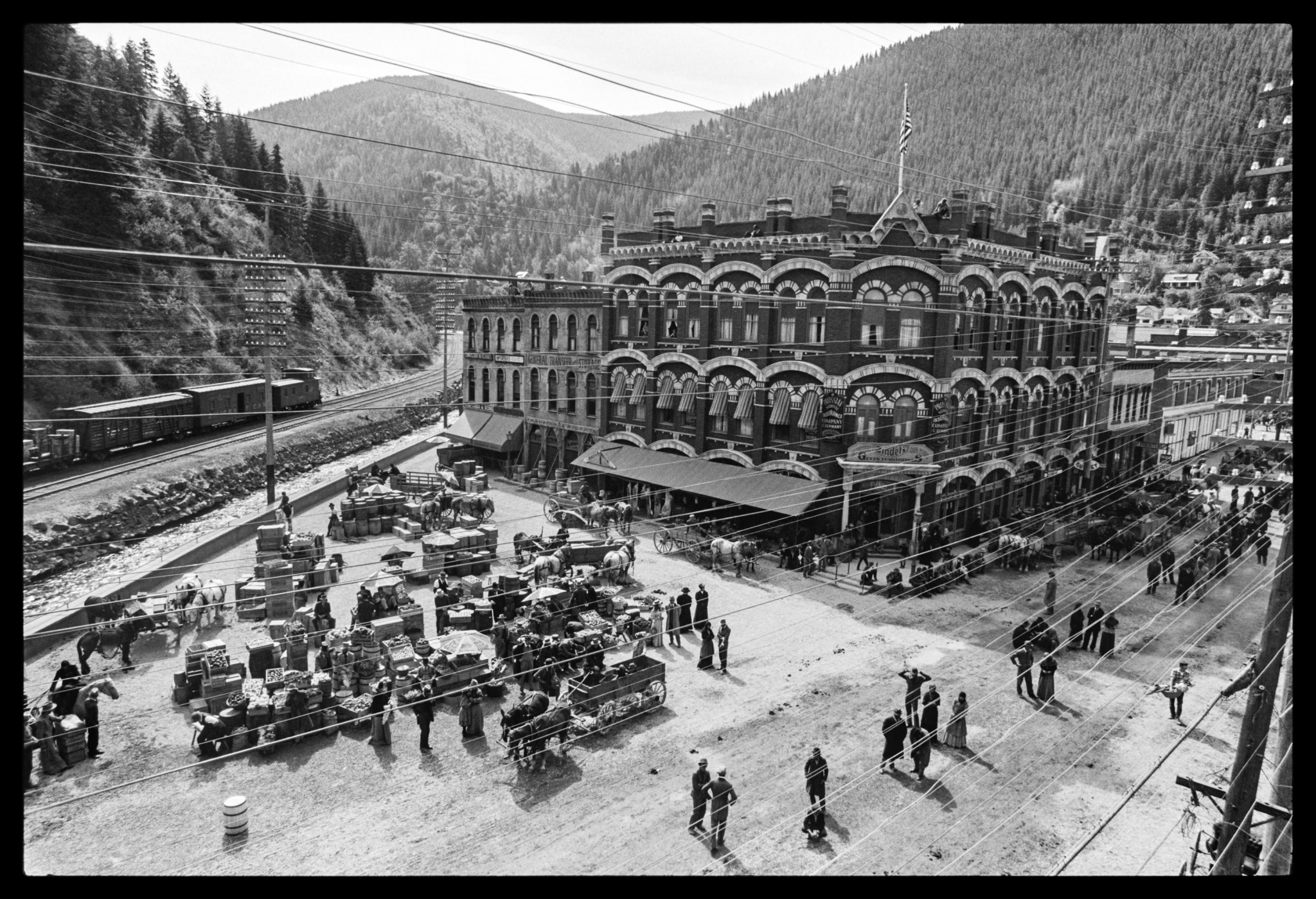

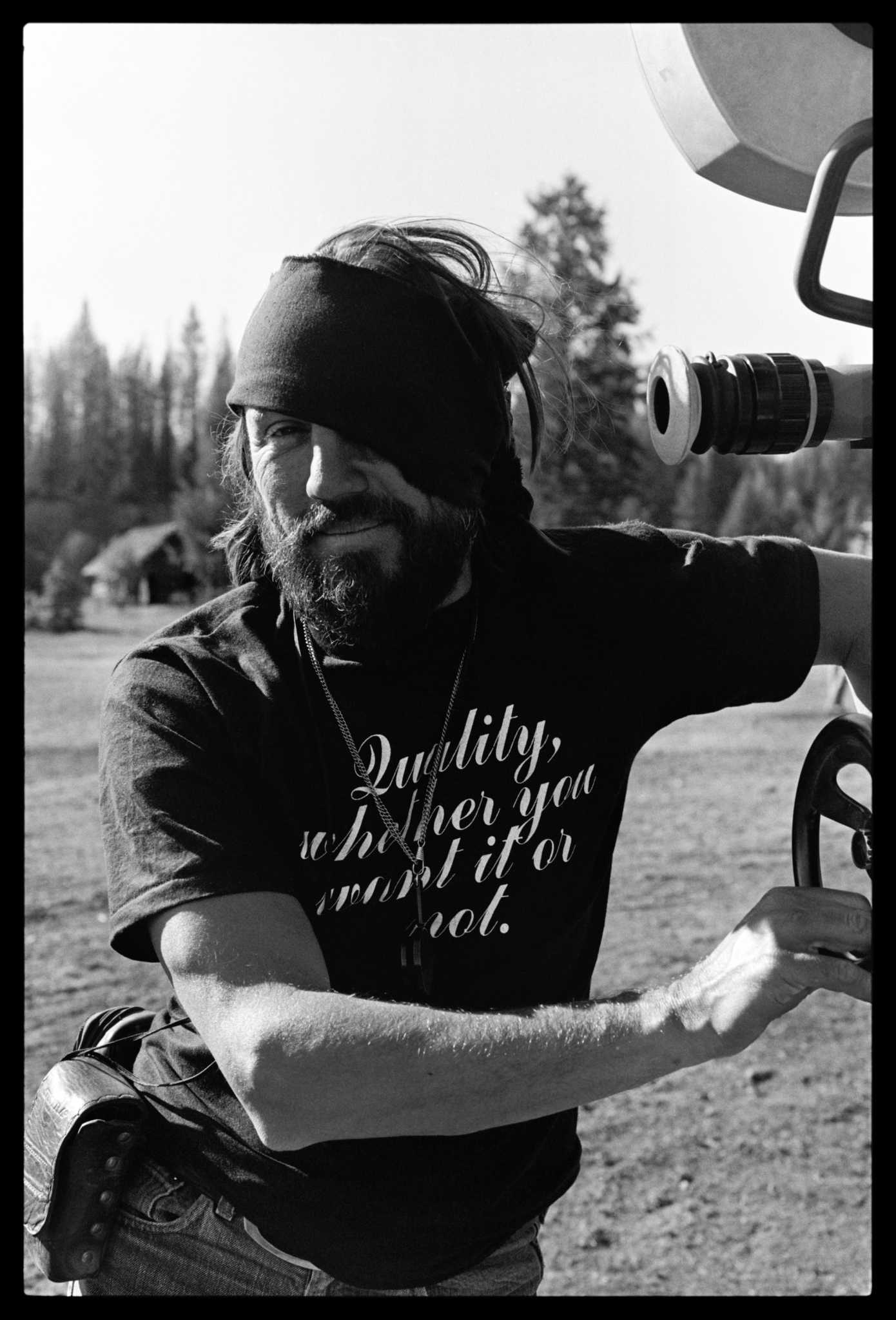

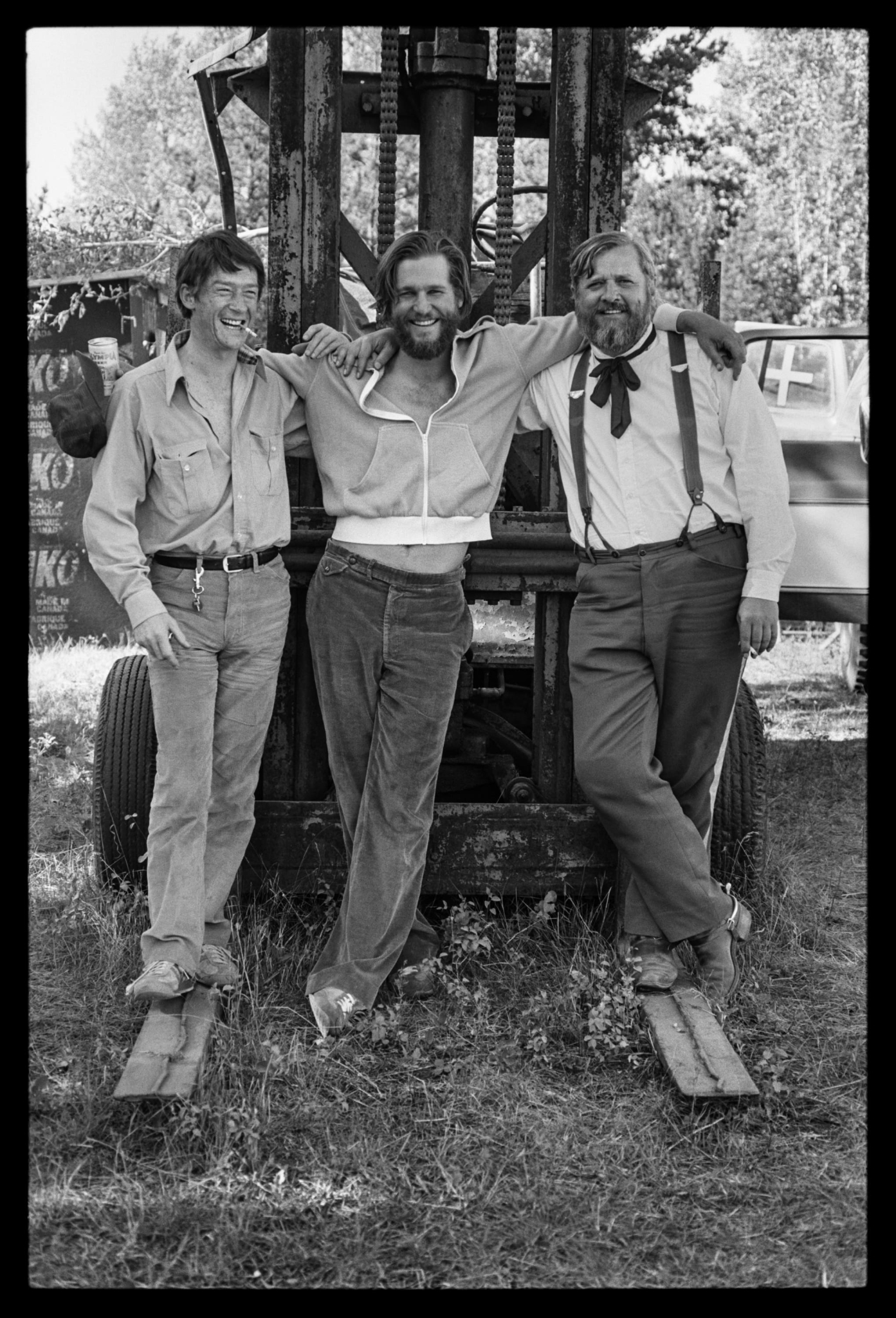

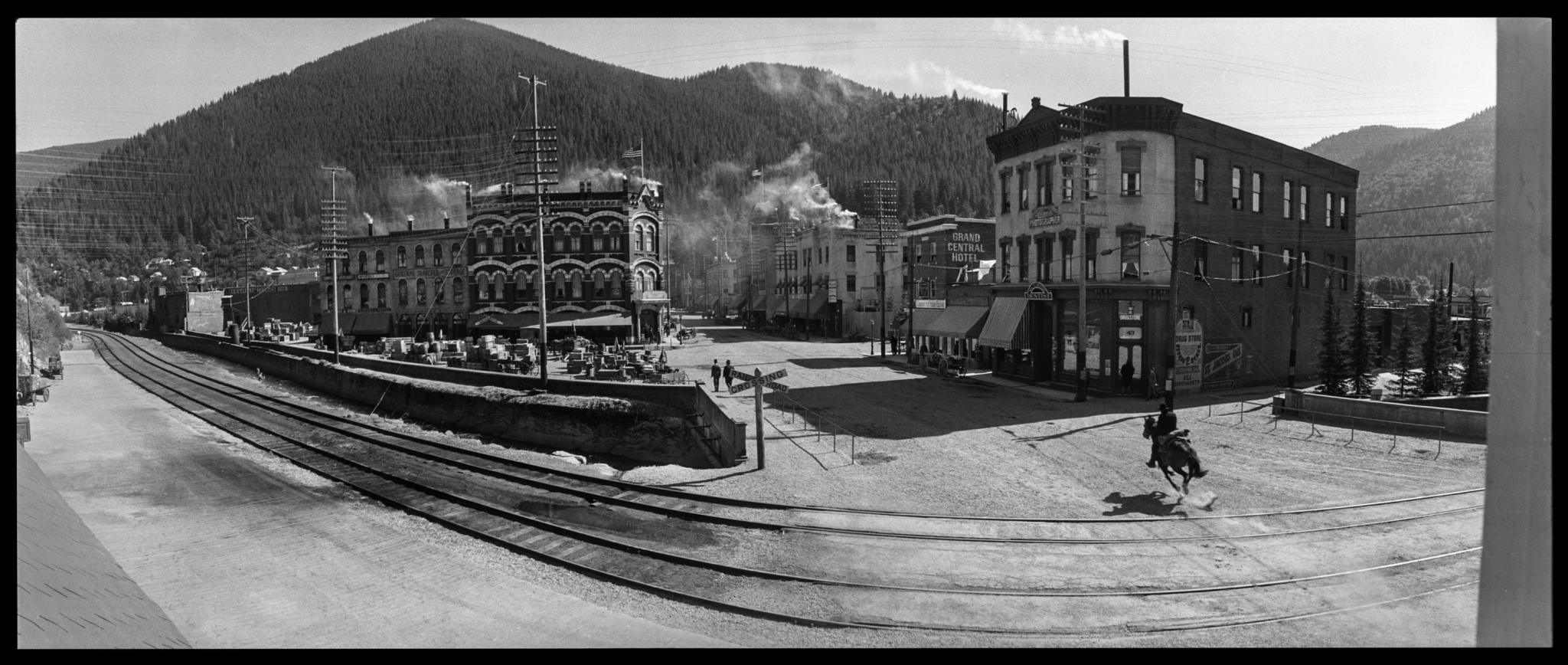

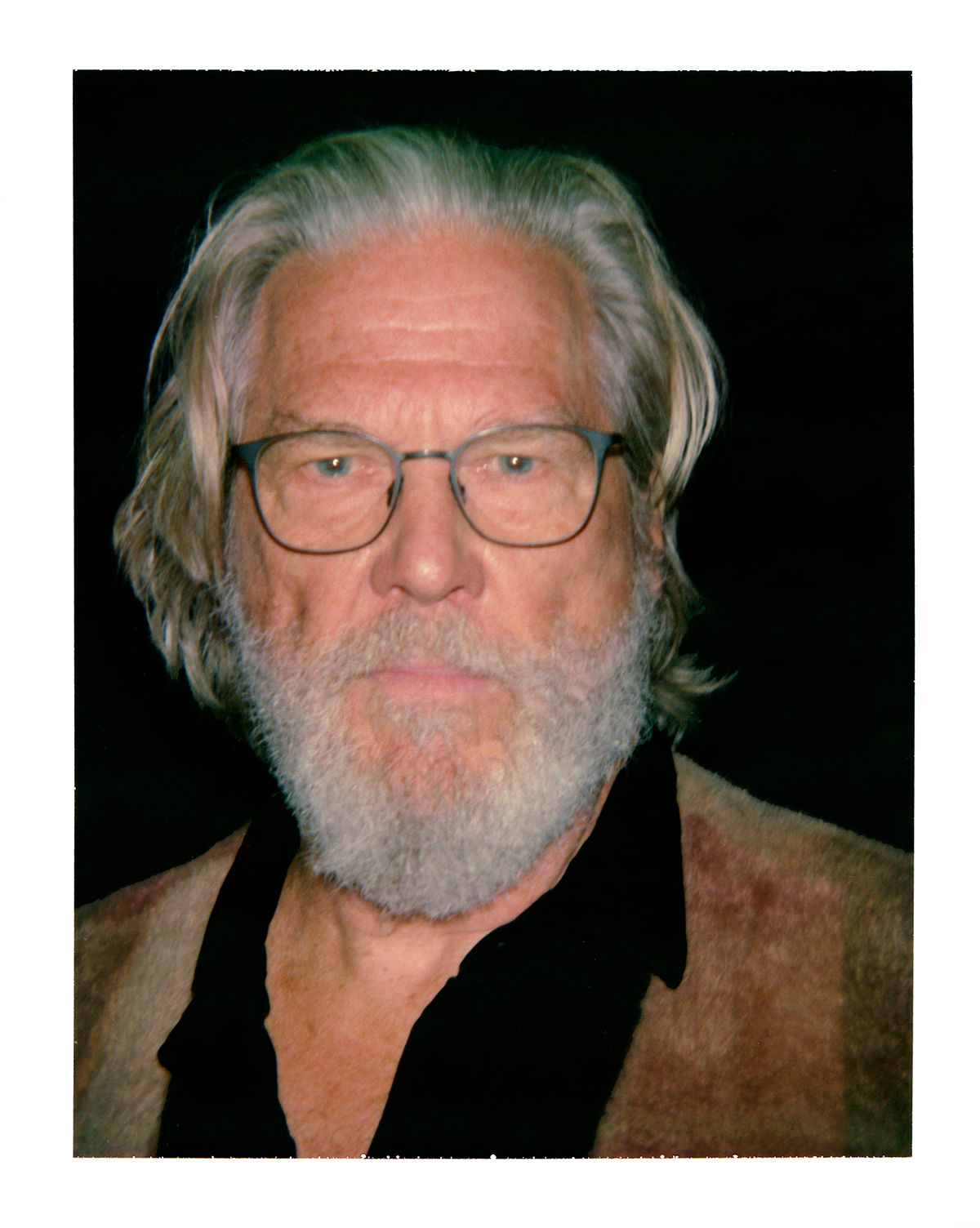

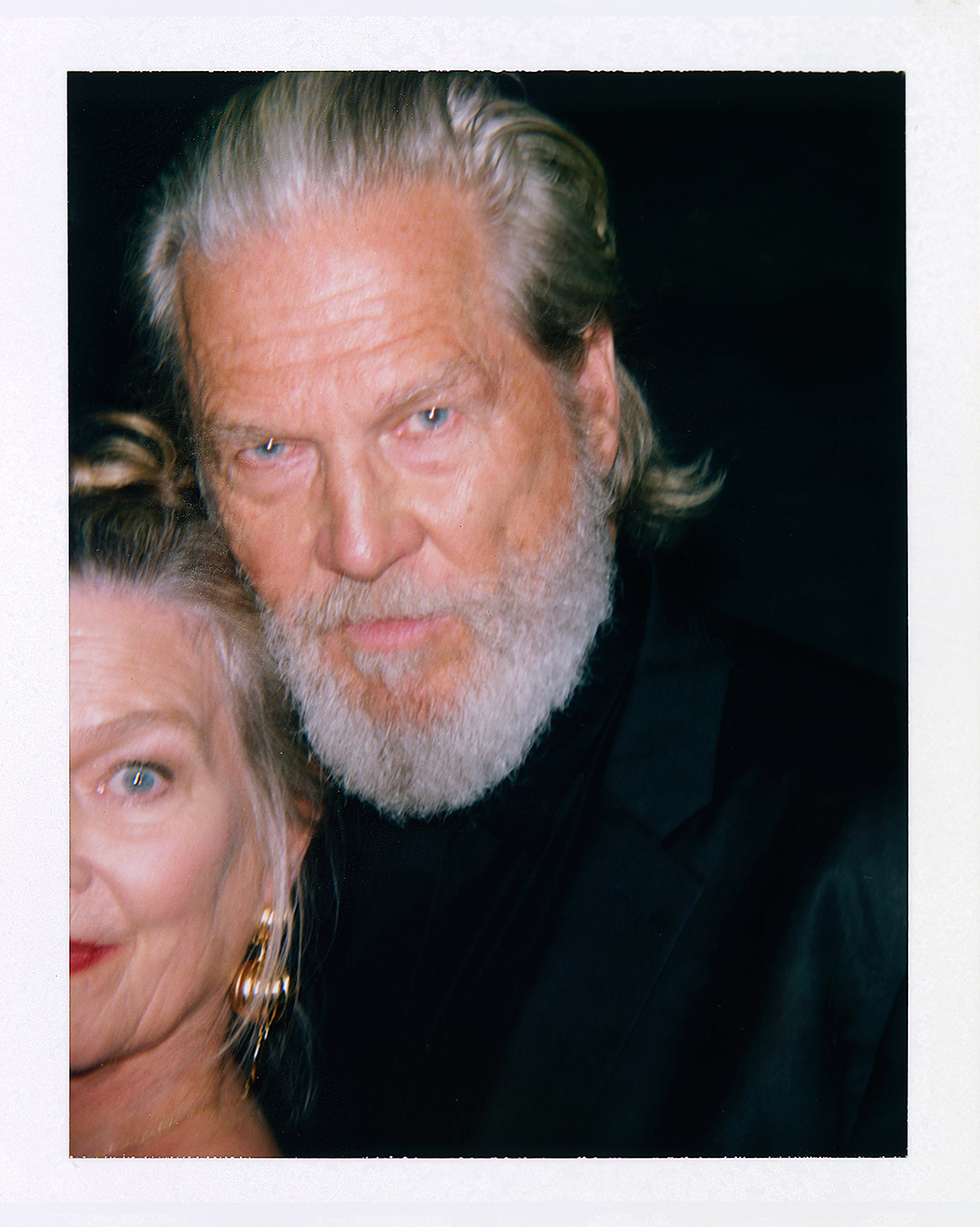

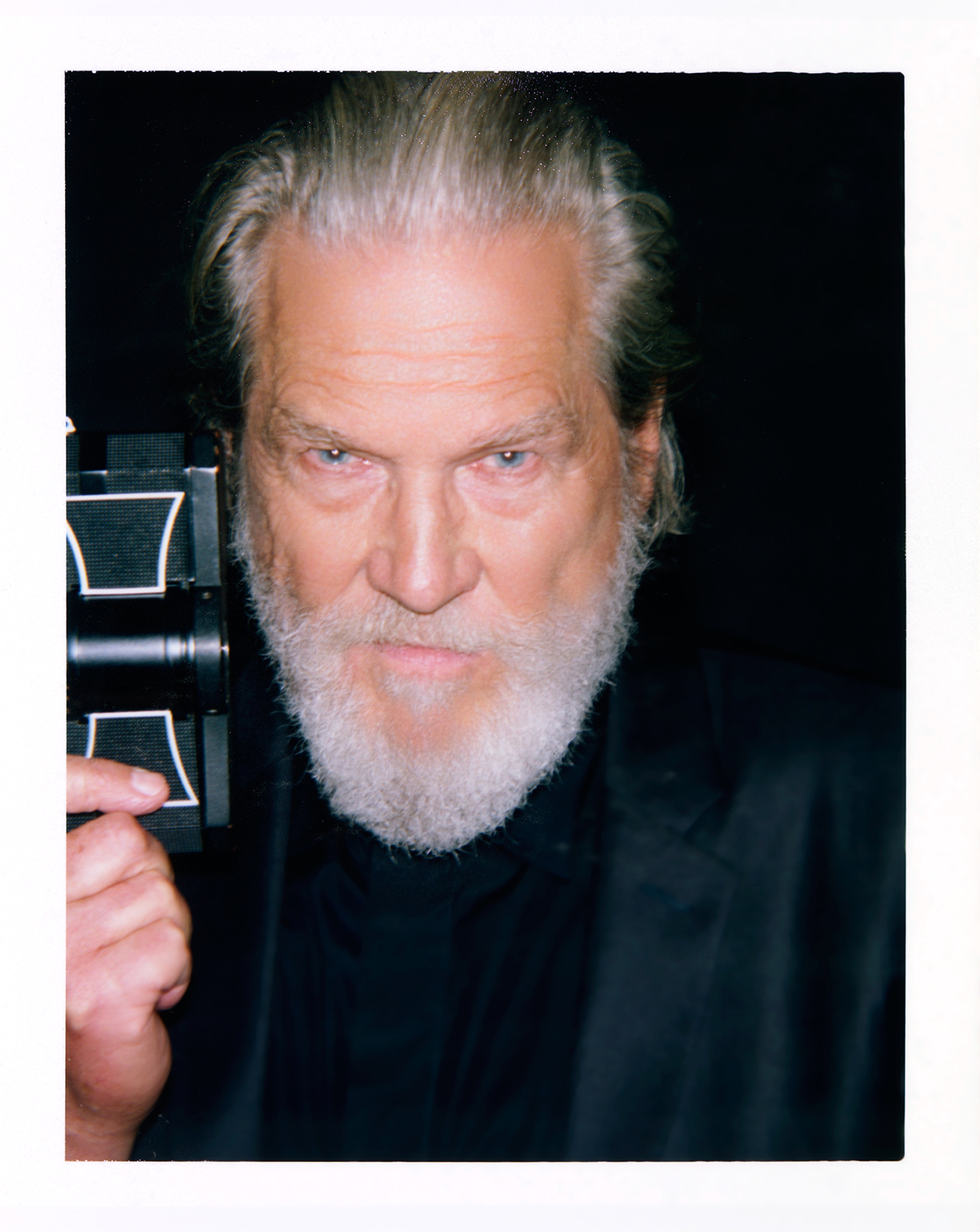

Even then, however, Susan Bridges—Heaven’s Gate’s on-set photographer and wife of one of its stars, Jeff Bridges—had captured a side of the epic that reflects the masterpiece it would eventually be appreciated as. Documenting the making of the film with her Widelux—a fully mechanical panoramic camera that has become a beloved tool for both Jeff and Susan—from inside the whirlwind itself, Bridges’ view of Heaven’s Gate explodes with humanity, an intimate collection of images that speak to the painstaking excitement of moviemaking and the shared community born from such an experience.

On November 15th, 45 years after the film’s initial release, both Jeff and Susan Bridges will proudly introduce a new restoration of the film’s director’s cut at the historic Arlington Theatre in their hometown of Santa Barbara, marking Heaven’s Gate’s triumphant return to the big screen. To boot, the screening is accompanied by an exhibition of Susan’s photographs from the film’s production, now open to the public at Santa Barbara’s Tamsen Gallery.

To mark the occasion, A Rabbit’s Foot creative director Fatima Khan—who previously spoke to Jeff way back in issue 7— journeyed to Santa Barbara to spend the day with the Bridges, who take us through their experience on the set of Heaven’s Gate, why the film has so resiliently stood the test of time, and their shared love of all things photography. Stay tuned for the full filmed documentary, releasing in the coming weeks. Until then, here’s a sneak peek at our time with the Bridges—starting with an exclusive conversation with Susan herself and a teaser for our short film starring the two.

You can buy tickets for the November 15th screening of Heaven’s Gate screening, with a special introduction by the Bridges, here.

Fatima Khan: Heaven’s Gate holds such a unique place in American cinema—both for its mythology and for what it captured on film. When you look back at your photographs from that set, what kind of world do they transport you back to?

Susan Bridges: I was young and in photography school when Heaven’s Gate was being filmed. It was a privilege for me to be a part of this production. There were many sets and locations, and they were all interesting. I had permission to wander and take photographs that spoke to me. I was a part of the film company, but also apart from it. Looking back on the photographs I’m transported to the place, and the memory of the people who worked on the film. Everyone worked hard. The days were grueling. The sets were often far from home base which was in Kalispell, Montana. The cast and crew had little time to eat and sleep before another long day began. I was encouraged by Michael Cimino and Joann Carelli to visit the sets and photograph what I wanted. Vilmos Zsigmond generously allowed me to follow his camera around and benefit from beautiful lighting and the glorious landscape. Film making is a collaborative art. There are many people doing many jobs to put all the pieces together. Sometimes the magic works and the result is a masterpiece. Or sometimes not. I had attended the University of Montana in Missoula and had many friends who lived close to the locations. It was fun to invite them to the set so they could experience the art of filmmaking.

FK: You were observing one of the most ambitious productions of its time through your lens. How did being behind the camera change your understanding of the filmmaking process—and of Jeff’s experience in it?

SB: Jeff and I celebrated our 2nd anniversary during the filming. I hadn’t been on many sets this extensively before. I saw the difficult part. The long hours, the tired people and the hurry up and wait. But I began to understand the rhythm of filmmaking. The actors were dressed in costumes, hair done, made up and ready to do their job when they were called for action. The hardworking crew had prepared the sets, the lighting, the blocking and the props for the shot. I could see the collaboration between the actors and the crew. They needed each other. I roamed freely on the sets. When the actors had a break, they were happy to pose for me. They gave me some beautiful photographs. They often stayed in character but sometimes relaxed. Jeff grew up on film and television sets. So, his experience was built in. I was able to observe and make my own decisions on what I wanted to photograph. Jeff had to leap into action when called, but I had more freedom to choose my game plan.

FK: What was your relationship like with the rest of the cast and crew?

SB: I felt like I was a part of the crew. They allowed me behind the scenes, and I ended up in some interesting places. I shadowed the crew to shoot action scenes, or I peeled off to take intimate portraits. I do enjoy being behind the camera, but it’s not always a quiet space. If I’m watching, I’m still involved in the scene in some way. It could be noisy and messy or a tender quiet moment. When it was quiet on set, I was able to be more reflective. When it was noisy, I needed to match the energy of the action. The battle scene was hot, dirty and loud. Although I wasn’t riding a horse around a circle or in a cart shooting a gun. I experienced fear, excitement and determination, like the actors.

FK: Your images from Heaven’s Gate feel both intimate and vast—much like the film itself. How did you approach capturing the human moments within such a monumental production?

SB: I really enjoyed the people. The crew was encouraging and the actors made themselves accessible. I made friends with them. We were living a shared experience, and I was a part of it.

FK: Photography can often become a way of remembering—or even reimagining time. When you revisit your old negatives or prints, what emotions or details surface that perhaps you didn’t notice in the moment?

SB: Getting proof sheets back can be surprising. You never know what you’re going to get. Maybe you captured something magical or maybe you forgot to load your camera. When I look at my photographs, I can feel the thundering of horse hooves, the sounds of gunshot and the smell of fear. It is quite wonderful to revisit the production that way. I experience the film in segments when I reflect on that time, now I see a complete picture.

“When I look at my photographs, I can feel the thundering of horse hooves, the sounds of gunshot and the smell of fear. It is quite wonderful to revisit the production that way. I experience the film in segments when I reflect on that time, now I see a complete picture.”

Susan Bridges

FK: Many of your negatives survived extraordinary loss—through fire, floods, and mudslides that destroyed several of your homes. When you decided to finally share the Heaven’s Gate photographs publicly, what did that survival mean to you? Did it feel like the work itself had insisted on being seen?

SB: I thought I had lost my Heaven’s Gate negatives in our latest disaster, a debris flow.

When I discovered they were safely in storage, I felt compelled to share them and I found the perfect spot. I was inspired by the Livingston Historical Depot located in a small town in Montana. It was built for President Teddy Roosevelt by the architect who designed Grand Central Station in New York. He traveled by rail from the East coast to Livingston. From there he headed South to dedicate Yellowstone Park, which would become the first National Park. Half the building was a train museum, and the other half was an art museum. I imagined my photographs on the walls. The room was two stories high, and I knew the widelux shots would look great printed big. I envisioned many of my photographs hanging on these historic walls. This would be the right place for my first exhibition. There is a wonderful local photographer and printer in town, Rob Park. When I saw his beautiful prints, it all came together.

FK: You used the Widelux panoramic camera on set—a format that literally bends time and space within a single frame. How did that choice influence the way you saw the production unfold, and what draws you to the Widelux as an instrument of storytelling?

SB: The Widelux, a panoramic or swing lens camera uses 35 mm film and gives the photographer a 140-degree image that captures more information than your eyes can see. I chose to use this camera in many ways. I took portraits as well as action scenes, like the photograph of a horseback rider racing through an old western town to warn the immigrants about the advancing mercenaries.

FK: You and Jeff have spent a lifetime creating—sometimes side by side, sometimes in completely different mediums. In what ways do your artistic worlds overlap or influence one another?

SB: Jeff put his Nikon camera in my hands and showed me how to use it. Photography was something we shared and enjoyed doing together. We are both visual people with different perspectives. I went to photography school and learned how the camera worked and found my vision through the lens. I learned how to read negatives and proof sheets and what a good print looks like. Jeff and I worked together in our dark room and found a mutual creative outlet. We traveled and worked together on many projects. When he was working, I would take my camera and explore. We admire many of the same photographers, including Lartigue and Atget, but have different perspectives and artistic visions. Mine included learning the art of hand tinting black and white photographs and his mastering the Widelux camera.

FK: Is there a particular photograph from Heaven’s Gate—or from any chapter of your life together—that feels especially personal or revealing to you now?

SB: Jeff and I have shared many chapters together and we have decades of photographs. I can’t possibly think of just one image that reveals our life together.

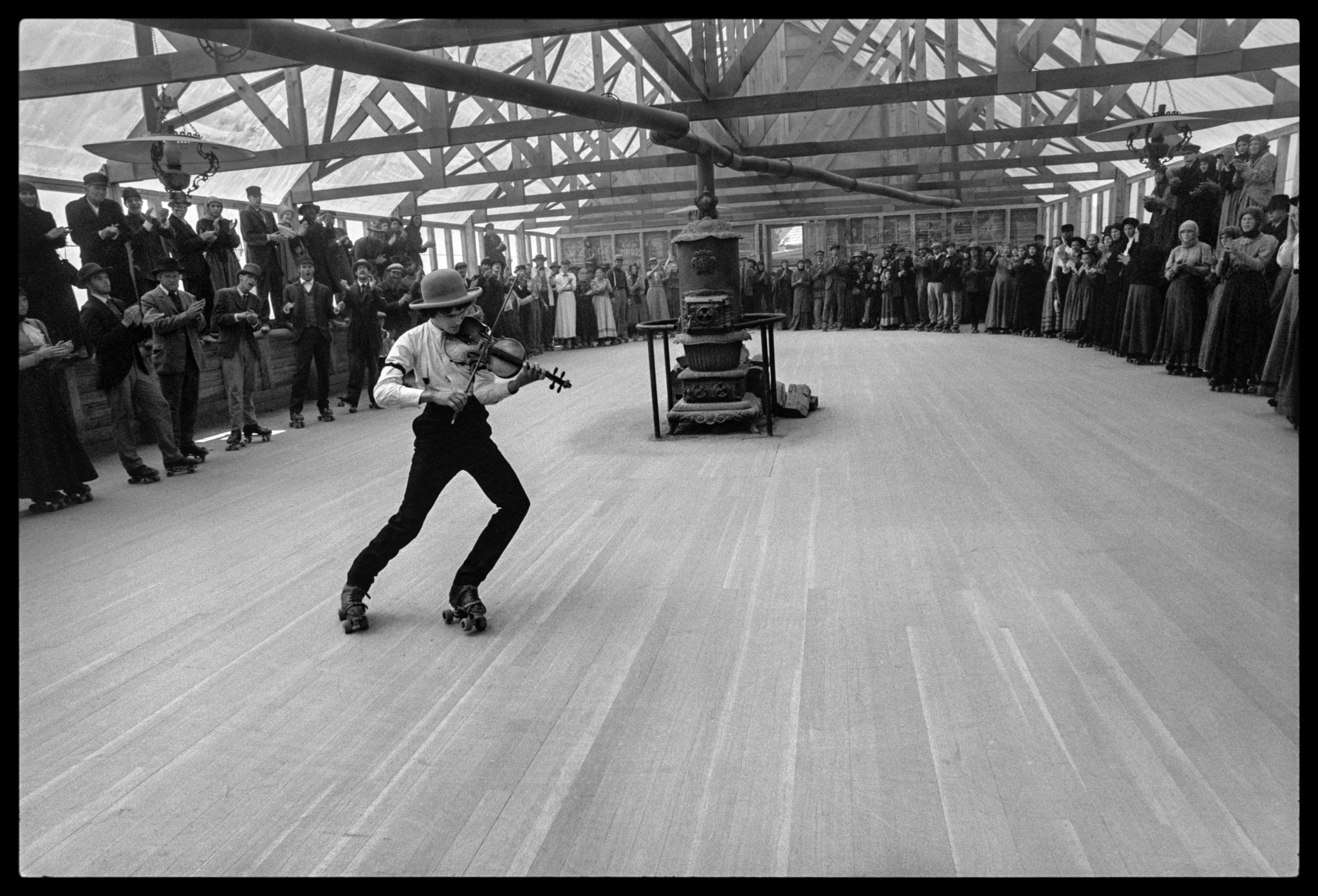

There is an image that speaks to me, however. I call this Widelux shot the Ghost Walkers. It captures the immigrants leaving the roller rink, named Heaven’s Gate. Many of the actors are departing from the rear of the tent, but a few seem to float towards us and out of the frame. It makes me think of the immigrants, many who were lost, but some survived and settled this country.

FK: If you could describe the experience of photographing Heaven’s Gate in a single image—something that isn’t in your archive but only exists in your memory—what would it look like?

SB: Kris Kristofferson brought his band, including T Bone Burnett, Stephen Bruton and many other talented musicians. The musicians were not only actors in the film but entertained us in our downtime. When I close my eyes, I see the joy on the faces of the laughing actors as they skate around the rink to lively music. This image in contrast to the harsh reality of immigrant’s lives remains with me.

You can visit the Tamsen Gallery to see the full range of Susan’s work on Heaven’s Gate—open now to the public.

Tamsen Gallery

1309 State Street

Santa Barbara, CA 93101

805.705.2208

Short Film coming soon. Executive Producer Charles Finch, created and written by Fatima Khan, directed by Matilda Montgomery. Director of Photography is Antonio Riestra, with Bobby Pavlovsky as Second DP. Light design and gaffer work by Max Wilbur, sound by Luis Molgaard. Research by Luke Georgiades. Hair and grooming by Candice Birns, and makeup by Cedric Jolivet.

Special thanks to Jana Anderson, Becky Pedretti, Joann Carelli, Miranda Mendoza, Hayk Sarkissian and the staff at the Arlington Theatre.