As her tenth novel My Sister and Other Lovers publishes this summer, Armani Syed pays a visit to the British writer by the Suffolk Coast to discuss shame, being a younger sister and living in the shadow of Sigmund.

Esther Freud collects me on the train platform of a sleepy coastal village in Suffolk wearing a floral black dress, dark shades and a welcoming smile. There is no detectable commonality that has brought me across the country to meet her. I’m about to leave my 20s, and she’s fairly new to her 60s. I’m a South London loyalist and she can only live around the perimeter of Hampstead Heath. My morning starts in Liverpool Street station, panting as I search for deodorant and sustenance before my train departs. Hers starts with a dip in the North Sea at her local beach, and preparations for an evening reading of her new, tenth novel, My Sister and Other Lovers, published in July.

But Freud and I are both unshakeably branded by our roles as youngest sisters. Her to fashion designer-cum-podcaster Bella Freud (as well as numerous other half siblings), and I to five high-achieving sisters and, notably, no brothers. This role forms the central motif in Freud’s semi-autobiographic novel, which follows narrator Lucy and her older sister Bea as they become young women, enter the tumultuous world of dating, and grapple with the consequences of a troubled family dynamic. The characters are reprised from Freud’s 1992 debut novel Hideous Kinky based on the two years of childhood that she and Bella spend in Morocco at the behest of their bohemian mother, Bernardine Coverley.

We drive to Freud’s countryside home where she spends about a third of the year when she is not in London. Freud purchased the home 14 years ago with her ex-husband, with whom she shares two sons and a daughter. “Have you ever been to Suffolk before?” Freud asks me. I confess that I tend to travel the U.K. along its length, and rarely across its breadth. “There’s something about being here, maybe because we’re by the sea. I can be here for eight weeks and hardly go anywhere in the car. You can cycle, you can walk, go to the next little town,” she says with an ease to her words.

Freud is of course the great-granddaughter of Sigmund Freud, the father of modern psychology. She is also one of the late painter Lucian Freud’s 14 acknowledged children. The family, she says, came to England from Berlin in 1933 when Hitler came to power. “It’s interesting how differently Jewish people reacted to that. Some people thought ‘it’ll blow over,’” says Freud. She recalls reading her grandparents’ letters for research and discovered that they were “really critically aware” that Germany was becoming unsafe for them. So they went in search of a new home, and a new holiday home, to replace the one they’d sacrificed in Hiddensee, an island in the Baltic Sea, west of Germany’s Rügen. They discovered a village between Aldeburgh and Southwold and since then, generations of Freuds have flocked there.

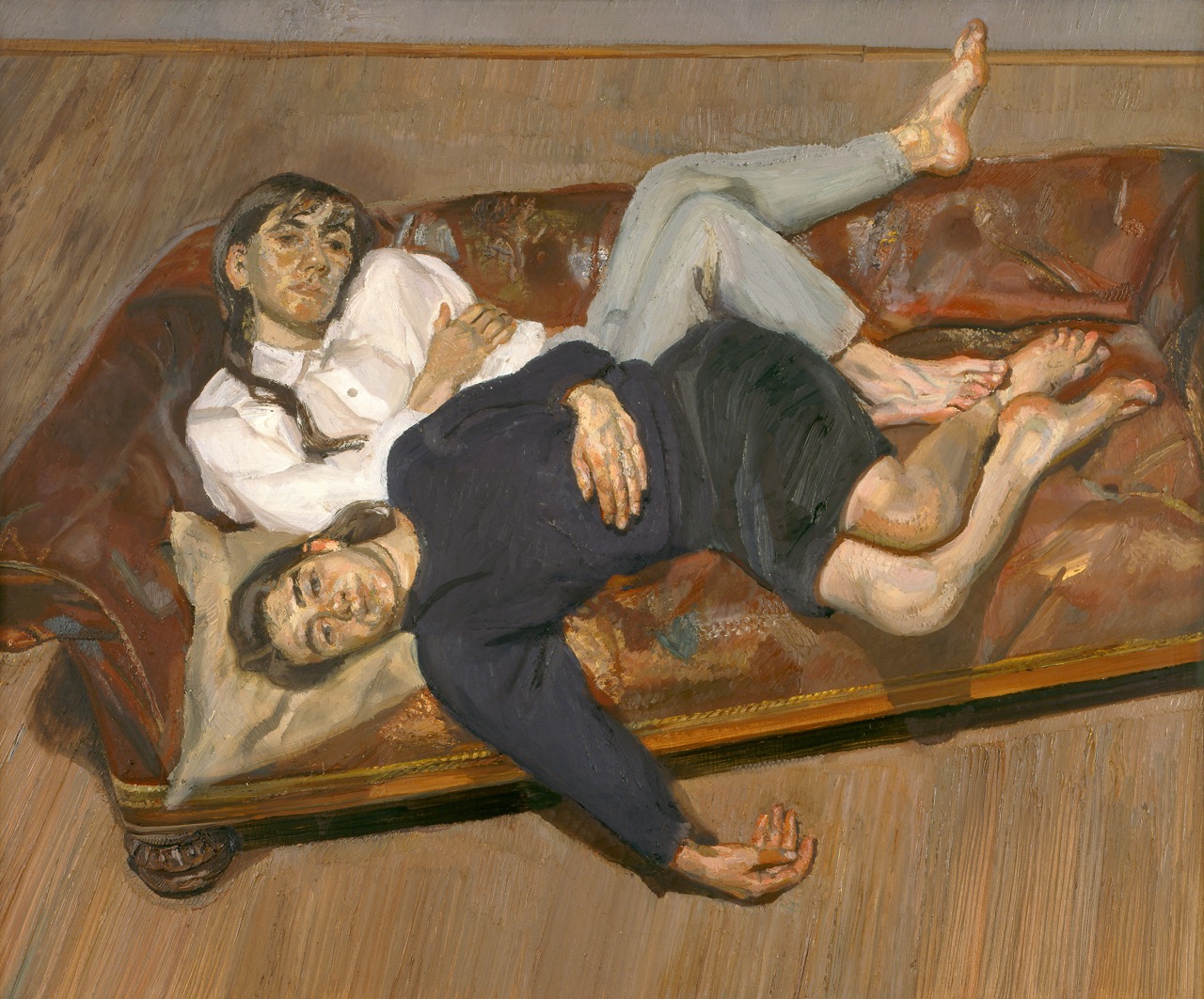

Bella and Esther, 1987-1988, The Lucien Freud Archive, Courtesy of Bridgeman Images

We pull up at the house. The Freud’s is an 18th century stone-faced cottage with exposed ceiling beams and rustic farmhouse interiors that would send TikTok’s cottage-core community into a frenzy. She fixes me an elderflower presse in the kitchen and we head outside to the summer house, where Freud would spend most mornings writing My Sister and Other Lovers. The impetus for the book, Freud says, was a prompt she put forward to the writing group she runs, during the pandemic.

The theme she chose was ‘The Journey’ and from it her short story—later published in The New Yorker— became the first chapter of the book. It follows the girls, and a peripheral half brother, on a journey to Ireland with their mother, newly single and unhoused; details their grandparents mustn’t find out. They hitchhike to Bantry, call in favours, and, comically, their mother panics and spends what little money she has on a George Harrison solo album. The novel pauses at the precipice before an eldest sister leaves the family home to start her adult life, leaving the youngest sister behind to take her place. “I felt this strong feeling when I was writing the story that, my gosh, this is the last time these two girls will be living together as a family,” Freud says.

Freud’s own journey was equally rootless. She was four years old when her mother moved her and Bella to Morocco for 18 months, delaying her education until she was six. When they moved back, one of the first places the sisters went was to Maynards, a sweet shop in Tunbridge Wells they often frequented, to see if the women who sold them Pick ‘N’ Mix had missed them. “We felt, at least I did, that they really loved us, and they would have been missing us too,” Freud recalls, who I find charming and quick with anecdotes, like a dream dinner party guest. We fall about laughing when she tells me the women, indeed, did not remember them. A good lesson in object permanence, we agree.

Freud could not yet read when she started at a Rudolph Steiner school in Sussex, and studied with the same teacher throughout her education. In 1979, she attended a London drama school that taught her to “toughen up” and take rejection as an actress, before pivoting to writing and publishing her first novel, Hideous Kinky, aged 28. The novel’s 1998 film adaptation would serendipitously see a 22-year-old Kate Winslet portray Freud’s mother just before James Cameron’s Titanic (1997) catapulted her into global stardom. “I met her in London. She had already filmed Titanic, but it hadn’t come out so she was wandering [around] as an anonymous woman,” Freud recalls. After chatting in Freud’s kitchen about the role, Winslet went in search of a good local pub. Freud followed up this win with her second novel, Peerless Flats, which saw her selected as one of Granta’s Best Young British Novelists in 1993.

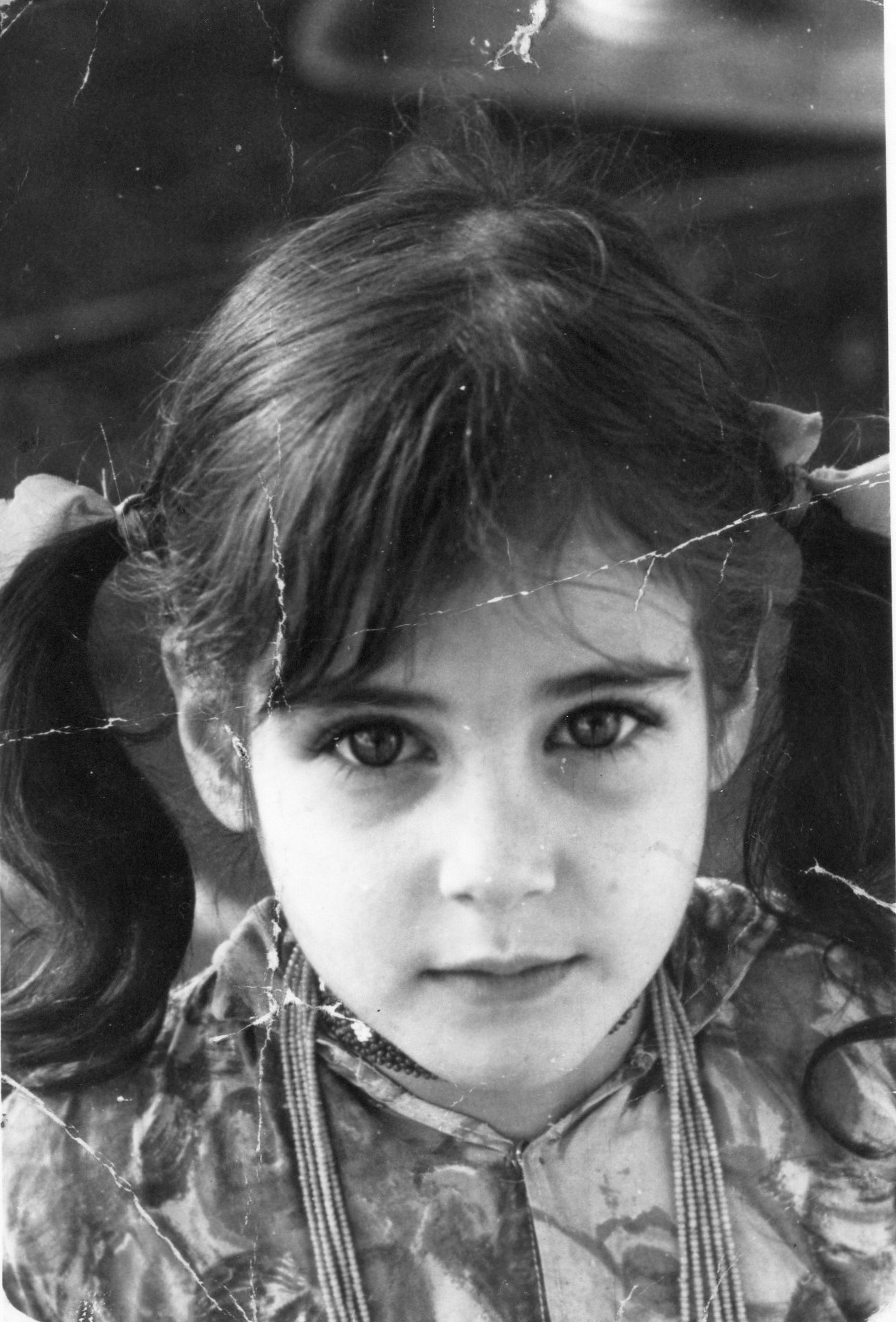

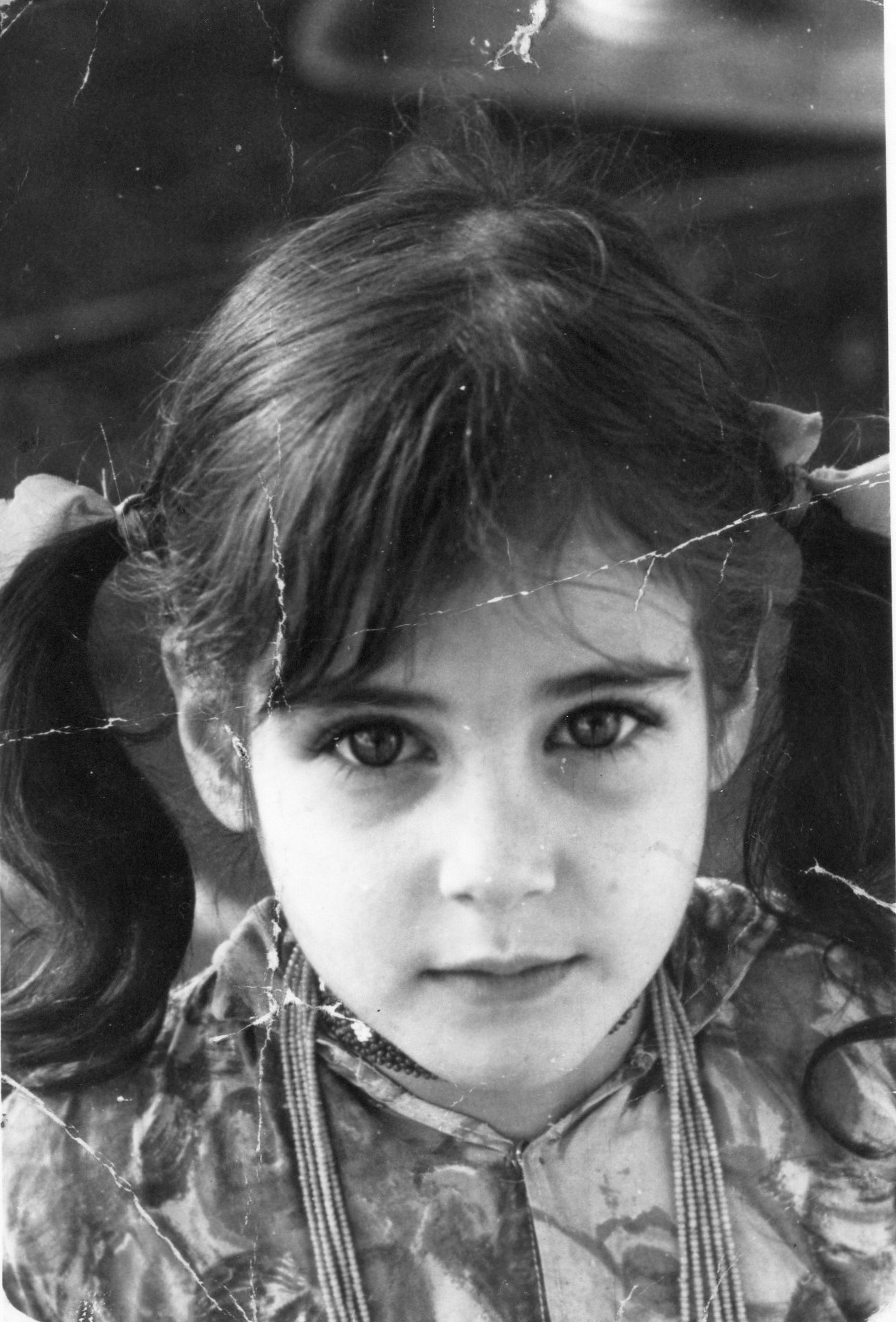

Esther Freud, aged five in Morocco. Courtesy of Esther Freud.

Freud is clearly not too precious to mine her own life or that of her family for a compelling narrative. She remains drawn to the stories of women in her family, because when it comes to the men, history books have said all there is to say about the Freuds. “In my family, women were always at the centre and the men were always hovering around the outskirts, so they didn’t seem so vital,” Freud says. While drafting her latest novel, she was cautious about what she could borrow from her sister but Bella encouraged her to be “quite fierce and razor sharp” with her storytelling. “My father used to say he didn’t like a painting if it was too easy on the eye. And in a way, Bella encouraged me for this book to not be easy on the heart,” Freud recalls.

My Sister and Other Lovers, has a different male character to irk every woman. A teenage boyfriend who makes an abortion all about him; a self-indulgent actor who is only attentive to Lucy when there’s a witness; and an academic who is “not good with… desertion.” But with every fling, situationship, and relationship that cycles through the novel, it is the older sister we long to return to the page even if she’s not being a good sister when she does reappear.

“The last I knew she was living back in London. I’d been in Soho when I’d seen her, walking along Gerrard street, and too surprised to care we’d fallen out, I’d run to catch her up. She took my hand, excited as a child, and asked if I’d like to see her room,” Lucy tells us in the novel. Freud perfectly captures the fragility of the sister feud, which has seen me place my own sister in Whatsapp archive jail, only to later bail her out of it to discuss gel manicure colours.

If Hideous Kinky and My Sister and Other Lovers are fictionalized renderings of her and Bella’s lives, then her ninth novel I Couldn’t Love You More (2021) was largely inspired by her mother Bernardine who met an artist and fell pregnant as a teenager. Freud’s mother felt compelled to hide the children she had out of wedlock from her strict Irish Catholic parents until they were age three and five respectively. Whereas the novel’s protagonist, on becoming pregnant, seeks the help of a priest and finds herself incarcerated in one of Ireland’s church-run mother and baby homes for ‘fallen’ women. Ran between 1922 to 1998, the homes lured vulnerable women with the promise of care, before soliciting years of work from them and taking their newborns away.

“I’m not sure how I would have written that story if my mother was alive, it wasn’t an area of life that she wanted to discuss,” Freud says, holding my gaze. She adds that she is a different writer since her parents both died in 2011. “Shame is a very powerful aspect of Catholicism, and even though she was such a warrior, she did carry that with her.” Shame rears its head again in My Sister and Other Lovers, as the fictional matriarch fails to acknowledge the childhood abuse that Bea experienced, which leads the latter to drug-fueled disappearances from the narrative.

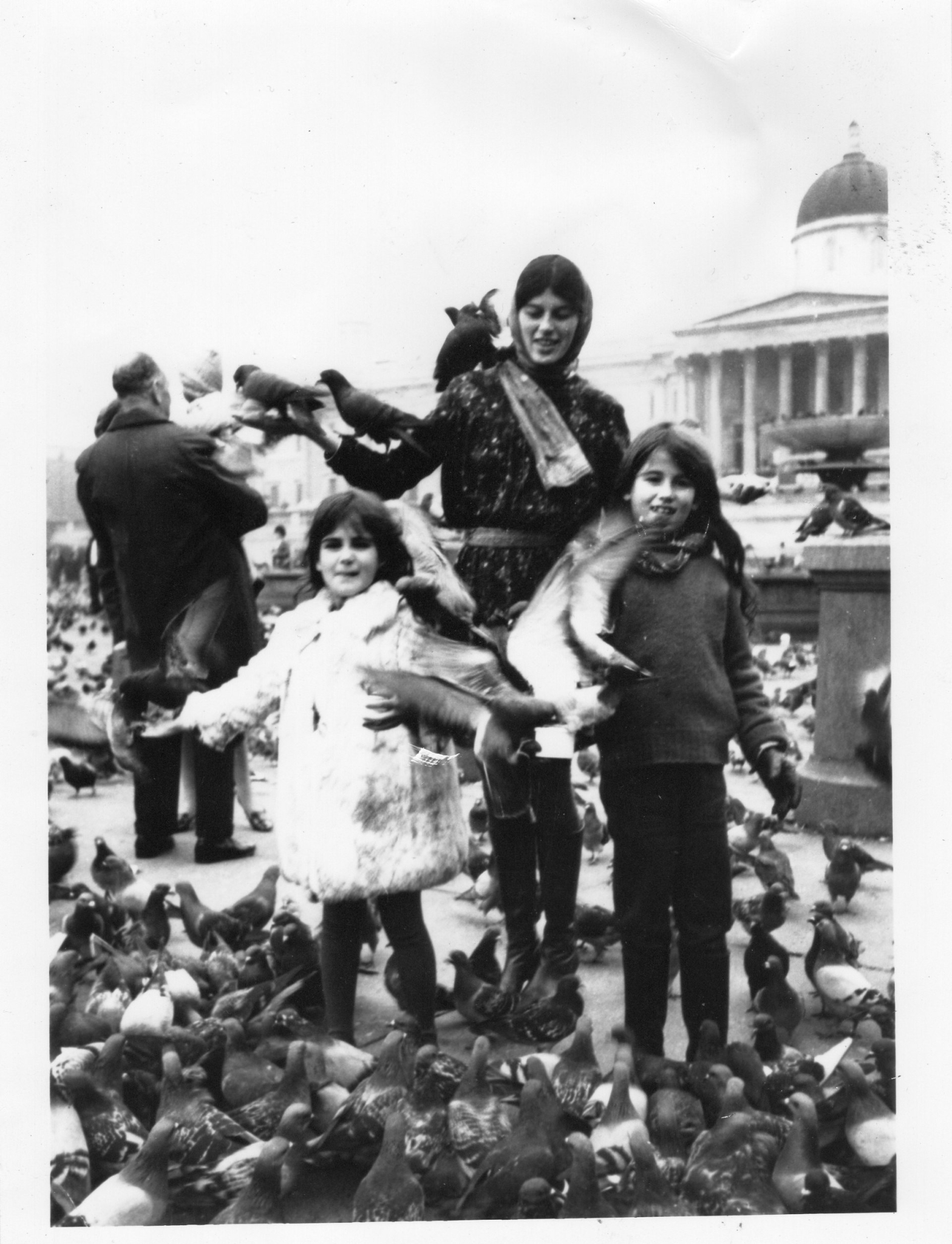

Esther and Bella Freud with their mother Bernardine Coverley in London’s Trafalgar Square.

I ask Freud what secret-keeping means between sisters. Growing up as the youngest, there is a sense of juvenile pride in being the keeper of your sister’s secrets, which can be as unserious as knowing about the party she has snuck off to. But for Freud, keeping secrets for someone with an addiction has a darker resonance. “It’s the cause of a huge amount of unhappiness, and keeps people very confused and in the dark,” she says. I’m taken aback by how vulnerable Freud is willing to be as she tells me that, until now, she’s almost never had a partner who wasn’t “an alcoholic of some kind.”

There’s a courtesy knock on the summer house and Freud’s partner appears at the door to speak with her. As she steps out, I take stock of the cabin-esque room full of shabby chic furnishing. A loveseat hanging from the ceiling by chains bobs to and fro with the light breeze. Her partner needs to rush back to London on the same train as me and her daughter will also be arriving in the afternoon with friends. I’m endeared by how quickly she springs into caretaker mode, suggesting a walk to the local deli to collect lunch for everyone, including me. We walk for no more than five minutes, she gestures in the direction of the sea and says she wishes she had time to show me the beach. We buy a collection of pies, rolls, and salads at the quaint store, and on the walk back I ask her where she was when she first heard Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 album Rumours.

In the novel, Lucy is urged by her friend Zara to come over by any means necessary—bus, taxi, or, as it turns out to be, a lift from a man —to listen to the now-iconic album. “It really was very similar, I had a friend at school who actually always had everything first,” Freud says, of the inspiration for the dialogue. “Sometimes I knew all the words from an album before I ever heard it because she would sing it.” Music adds contours to each chapter of the novel. In fact, in its earlier form, the book was a collection of short stories, each named after a musician. As these merged into one cohesive novel, the presence of music remained in each chapter; we revisit Elvis’ death, Bob Marley’s childhood home on Lucy’s trip to Jamaica, and Al Green’s timeless hit Let’s Stay Together forms the soundtrack to a sisterly moment.

Music taste, as I can attest, is often inherited from an older sibling, and only revised in adulthood. My sister closest to me in age grew up in the chokehold of indie sleaze, spanning from 2006 to 2012, and thanks to her I was loading The Libertines, MGMT, and Vampire Weekend onto my iPod. For Freud it was quite the same; Bella was their collective tastemaker and this has bled into her novel. In an early chapter, Lucy describes an electronic track as a song she’s been “encouraged” to despise. The encouragement in question no doubt came from Bea. Bella is also the reason Freud, to this day, is “utterly loyal” to ABBA slander. “Now, everyone seems to think ABBA are musical geniuses,” Freud laughs, “I’m being left behind.”

“In my family, women were always at the centre and the men were always hovering around the outskirts, so they didn’t seem so vital.”

Esther Freud

Freud knows she and Bella look quite alike. “I don’t know if she’s mistaken for me, but I’m quite often mistaken for her,” she tells me. There’s a Freudian joke to be made about doppelgängers but it feels like low-hanging fruit. Clothing, however, is where the sisters’ appearances diverge, Freud says. Her fashion designer sister—who worked for Vivienne Westwood in the 1980s before launching her eponymous womenswear label in 1990—has always had androgynous style with a focus on tailoring. “I’ve always veered towards, as she calls it, ‘a precious princess,’” Freud says, quoting Bella’s conversation with the Haim sisters on her podcast Fashion Neurosis.

The podcast sees Bella inviting tastemakers and celebrities to lay on her couch and offer up their innermost thoughts with fashion as the entry point to the interview. The show’s guest history has included fashion titans, from Kate Moss to Jonathan Anderson, as well as culture figures Cate Blanchett, Eric Cantona, and Courtney Love. Can we expect Freud on her sister’s sofa any time soon? “I just don’t know if I have enough to say about fashion,” Freud insists, adding that she will often wear clothes from Bella’s collection when meeting up with her to escape any judgment from her older sister’s sartorial eye.

From Lydia Bennet disgracing her family by running off with Wickham in Pride and Prejudice, to Amy March burning her sister Jo’s creative writing in Little Women, classic literature would have us believe the youngest sister is naive at best or petulant and spoiled at worst. But in Freud’s fiction, there’s space for a youngest sister to be the mediator between an agitated mother and wounded older sister, plagued by loyalty to both. Perhaps this is how Lucy inadvertently answers to, as she puts it, “The quandary of the younger sister—what to do when it had already been done.”

Back in the car and speeding to the station, Freud is still reflecting on being the youngest. She gestures at her partner in the driver’s seat and tells me he is also from our tribe. After a moment she turns to me in the backseat and cheekily says, “With older siblings you just have to accept, they don’t actually think you’re an entirely formed human being.” On the train home I put this to my sisters on our group chat, and no one responds.

My Sister and Other Lovers by Esther Freud is published by Bloomsbury.

Main image: Esther and Bella Freud. Courtesy of Julian Broad.