The essayist and critic Durga Chew-Bose describes how she brought Françoise Sagan’s notorious novel—a tale of sex and death in the South of France—to life.

When it was first published in 1954, Bonjour Tristesse, Françoise Sagan’s mnemonic tale of transgression and adolescent reckoning in the south of France, was a succès de scandale, with the 18-year-old Sagan achieving overnight notoriety for her tale that skirted the edges of taboo. Quickly adapted for film by Otto Preminger, starring Jean Seberg, it has now been taken on by the Montreal-based writer Durga Chew-Bose. Her contemporary version follows the same plot as its predecessors: a simple holiday between the ingénue Cécile (Lily McInerny), her playboy father Raymond (Claes Bang), and his girlfriend Elsa (Naïlia Harzoune), is interrupted when Anne (a cold-blooded and hair- clipped Chloë Sevigny) joins them. Anne is an old friend of Cécile’s mother, and a triangle is created between Anne, Elsa, and Raymond. Cécile, experiencing her sexual awakening with Cyrile, sees her own life threatened, leading to schemes and manipulations that will sear forever in her consciousness. With a sensibility for the literary, Chew-Bose approaches her adaptation of the book’s long, hot, tragic summer as if she is showing a memory—illusive and aching—accentuated each time they are remembered anew.

An essayist and critic, Chew-Bose has contributed to publications such as n+1, Interview, Paper, and Rolling Stone, and has released a book of essays, Too Much and Not the Mood (2017), named after a fragment in the diaries of Virginia Woolf. Here Chew-Bose discusses her inspirations for the adaptation—also her directorial debut— which she sees as continuing the fervour and fascination that has always encircled the novel.

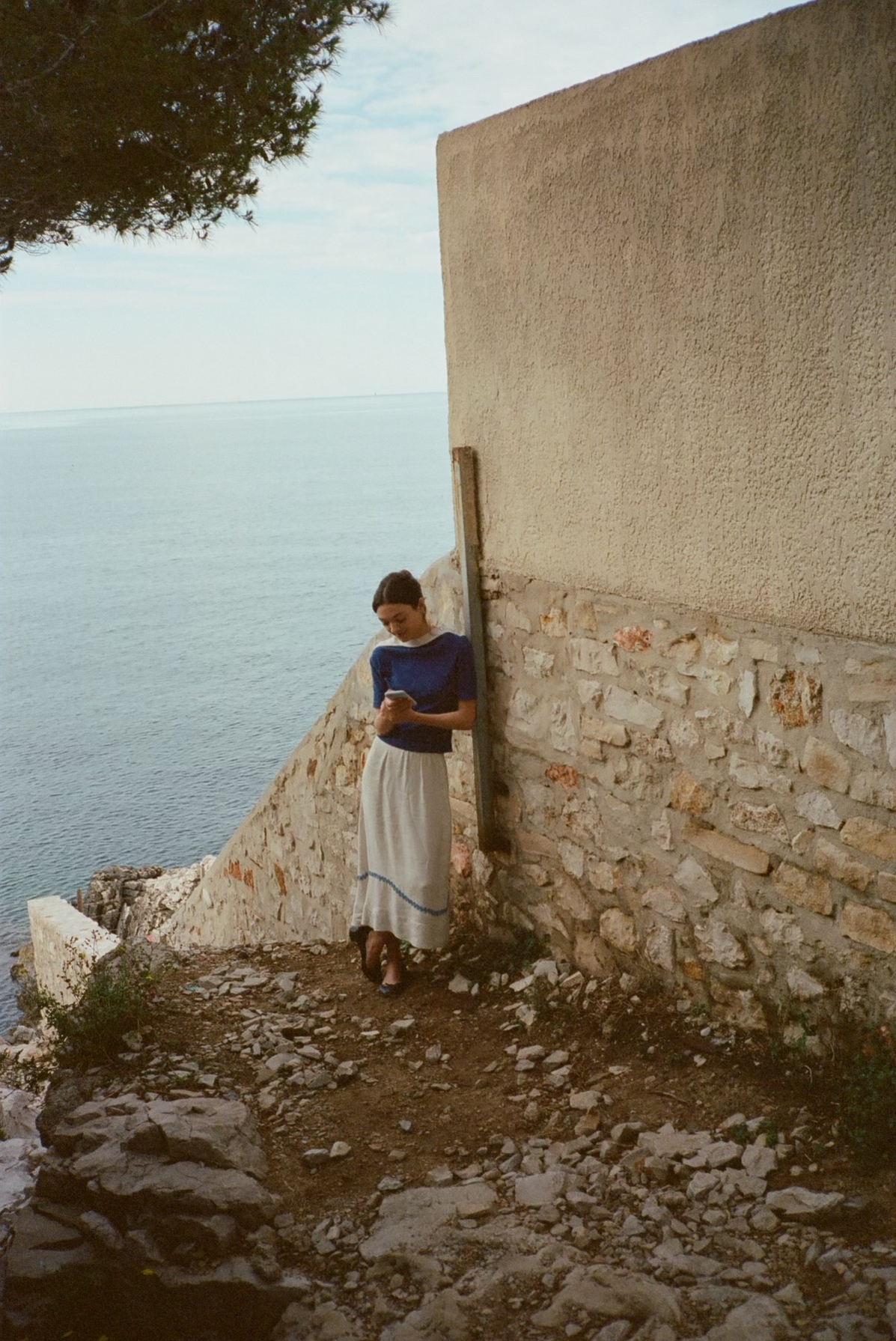

Lili McInerny on the set of Bonjour Tristesse (2025). Shot by Miyako Bellizi.

I don’t remember the first time I read Bonjour Tristesse. I was much younger, I don’t think it left the biggest impact on me—it was just a book that everyone was reading. For a lot of people there are certain books which arrive at a certain period of time. Everyone was reading The Catcher in the Rye (1951) when they were 13 or 14 and it was given to you by an aunt or something. When my producers reached out to me to adapt it as a screenplay, I knew I had to revisit it. It wasn’t going to be fresh enough in my mind to just start adapting it from memory. You know how someone will tell you a memory from childhood, but you’ve seen it in a photograph, so you’re not totally sure if it’s your memory or the photograph? I’d also seen the Otto Preminger adaptation of Bonjour Tristesse (1958). I love that film. So there’s this weird mix of the movie and the book in my memory.

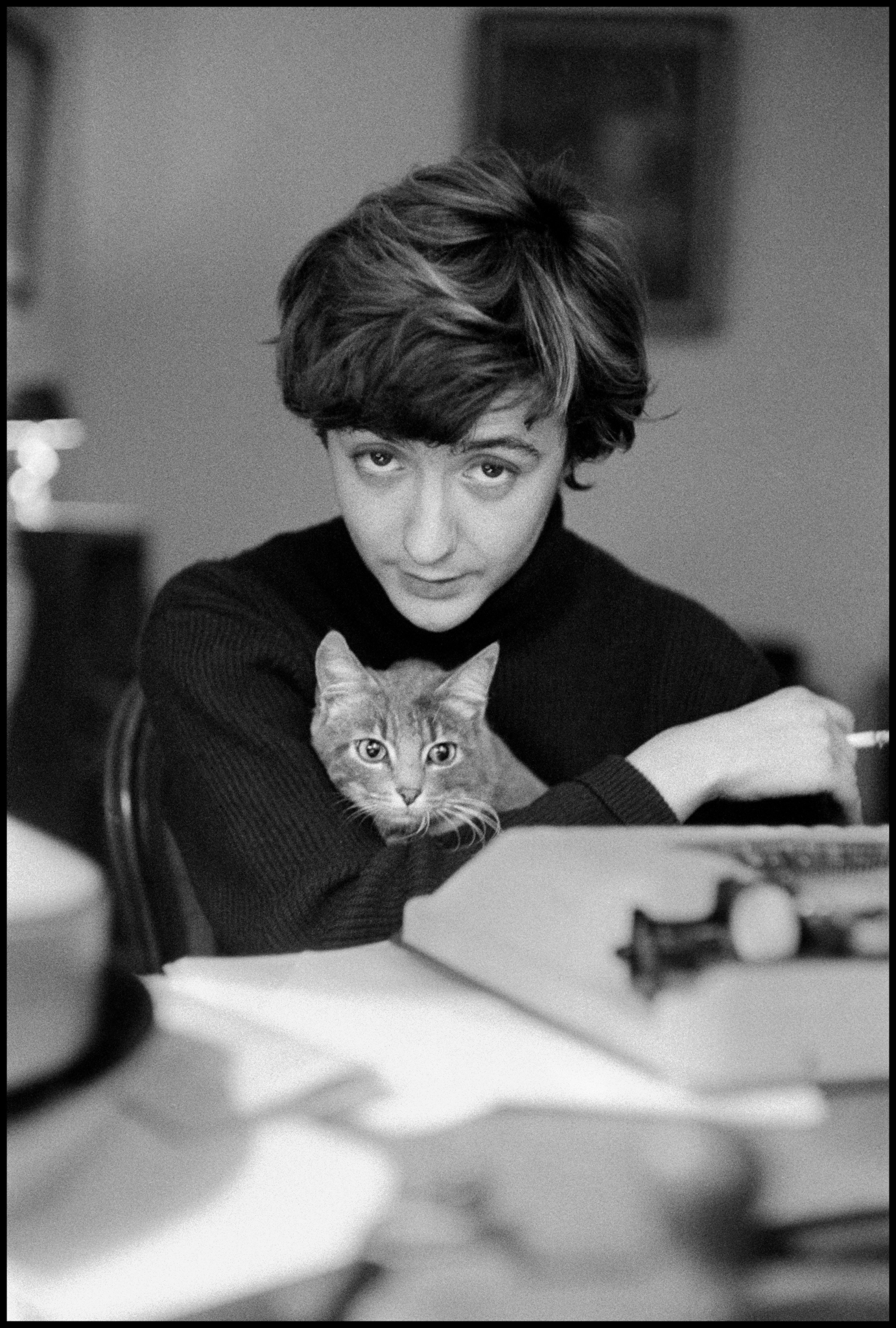

I knew all the lore around Françoise Sagan. She’s very mixed into the sensational moment of the book because she was so young and it was so scandalous at the time. I feel like her, the book, and then the Preminger film, which was adapted only four years after the book, are all part of its own story. You think of Bonjour Tristesse and you think of Jean Seberg’s face and cropped haircut. But is it Françoise’s haircut you’re thinking of? It’s sort of a mixed-media memory. I’m struck by all of it together. It’s all enmeshed. And when I adapted it, I wanted it to be a continuation. I am part of the fever, as opposed to mine being the ‘new version’.

Not to sound unromantic, but I was hired to revisit it. So I was reading it with that momentum you have when something is an assignment. I think that was good for me, that I wasn’t just reading it sitting outside one day, because it fell into my lap. So I was finding out what it was, but I was also trying to let it tell me what it was. Because it’s such a beloved book, I didn’t just want to adapt it for the sake of it. There needed to be some way in. And I think the best way to find your voice is to listen for it. So I read the book and any time an image had its way with me—it didn’t matter if it was the way a character says something or an image; you know that perceptible moment where some piece of art just picks you?—I would just write it down. And I built my adaptation around that. Like the first image of the film is certainly not the page of the book. At one point Cyril, the young man that Cécile has a relationship with, describes her as a dead body on the beach. I thought I wanted to start there. There was no strategy. The choice just said that’s what you have to do. That was my way of adaptation: letting the book tell me what it was.

I tried to stick to Cécile’s point of view as much as I could. The book is written in the first person, but we chose not to have narration in the film. I wanted it to have a literary feel. There’s a mannered way the characters speak. You definitely feel like you’re in another world, even though it feels familiar, too. That felt to me very much in the world of becoming. You think, are we watching her experience of the summer? Are we experiencing her memory of the summer? The way we remember a woman who alters our perception of womanhood, or the way we remember what our relationship was like with our father before something tragic happens. Or before we come into ourselves.

This whole notion of being perceived and perceiving to me is very linked to the idea of womanhood. Being in that liminal space. Of all the seasons, summer is the best one to show this because it is very slow and seductive, and there’s skin and there’s sweat and you’re squinting. Everything’s a bit out of focus.

All the characters are becoming themselves in this adaptation. Like they are experiencing a variety of growing pains or choices that ultimately don’t necessarily put them at ease. Or they are confronted with themselves by a person who knows them really well. It’s a coming of age for Cécile but there are different moments of impact for Raymond and Elsa and Anne as well.

We spoke a lot on set about how we wanted to portray the taboo of the father-daughter relationship. It’s between the lines in the book. It’s definitely pushed further in the Preminger adaptation. But we thought also, how do we actually want to ignore that and just show nearness and closeness and intimacy and vulnerability? If an audience interprets that in a way that makes them feel uncomfortable, maybe that’s more of a mirror on the audience than the story we are telling. I’ve always loved father-daughter films—Paper Moon (1973) comes to mind. Contact (1997) is a film I love, with Jodie Foster, and À nos amours (1983) by Maurice Pialat. It’s such a great relationship to present on screen, because there’s so much at play. There’s an element of the father-daughter dynamic that has always felt like cowboys to me. They’re the last ones left. It’s sundown and they’re exhausted and reflecting on the day. There’s a scene in my Bonjour Tristesse where Cécile and Raymond are having a cigarette alone on the balcony. I told Lily and Claes this was their cowboy scene. It implied a certain masculinity, wildness, something outside of the law.

I went to college with Lily’s cousin. When I graduated from college I was living and working in New York, and one of my many jobs was going over to Lily and her brother Roger’s house to spend time with them while their parents were going to the theatre or had dinner plans. I hesitate to use the word babysit because they were older and New York kids don’t need to be babysat. Lily has always had this boundless energy and it makes complete sense to me she has found her passion as an actress. Making a movie takes forever so there’s something nice about this first one being made with someone I knew prior. It feels like it was even longer in the making.

Chloë Sevigny is eternal. At the beginning I was detailing who I thought Anne was and what I wanted to do with her. And one of my producers said it sounds like Chloë. There are so many puzzle pieces to making a movie—names get thrown around, and this was many years prior to casting her. But her name kind of stayed lodged somewhere there. You have to prepare yourself for heartbreak. But Chloë’s always been orbiting the role in my mind. Partly because I’d never seen her do anything like that. Anne being buttoned-up is also a defence mechanism. A way of protecting herself or fortifying who she is. Then she also subverts that in scenes where she is just having a conversation. With Cécile, sitting on the edge of her bed or when she is listening and reading alone. There’s a softness to her too, that is very natural to Chloë.

Anne is a fashion designer. It required me to do this world-building for her that had a backstory. What are her designs like? Where is she in her career? Who does she design clothes for? What is her relationship to beauty, to work? Miyako Bellizzi, the costume designer, and I wanted to work with our friend Cynthia Merhej, who is the designer behind Renaissance Renaissance. Her designs are quite feminine and romantic, and have an element that is quite costume-adjacent, so it suited the film in terms of building a sense of fantasy. That was a fun element. Not just costuming the character Anne, but building the world of her designs and sketchbooks, and the white dress she gives to Cécile. For Raymond, Miyako and I felt that in some way he presents himself in a very traditional, orthodox way of being a man, but then he does his ballet exercises in the morning in high-waisted pants. Is he a little old- fashioned or is he actually quite vain? Raymond is a bit lost. I think that’s a very vulnerable place to be, not just as a father, but as a lover. He’s being changed by someone from his past re-entering. I think his vulnerability was really something that interested me more than his want for escape.

Elsa is just so extraordinary. In the Preminger adaptation she was very thinly developed, for the potential of what an adaptation could do. I really saw her as an opportunity. We have Cécile as one version of womanhood or becoming a woman, and then there’s Anne as well as Natalie, Cyrile’s mother, who are women. Elsa and Cécile have a more sisterly bond, but she’s also her father’s girlfriend. I actually perceived Elsa as sometimes the smartest person in the room who won’t be affected by things that might slow other people down—like heartbreak or being shortchanged. She sees it all and has an impossible coolness to her that keeps her a bit distanced but ready to go at any minute. She is also warm and loving, and wise beyond her years. In the book she could be perceived more like a Gatsby, joie de vivre figure, but I wanted to give her more weight and impact and these moments with Cécile where she says life’s truisms that Cécile can pocket.

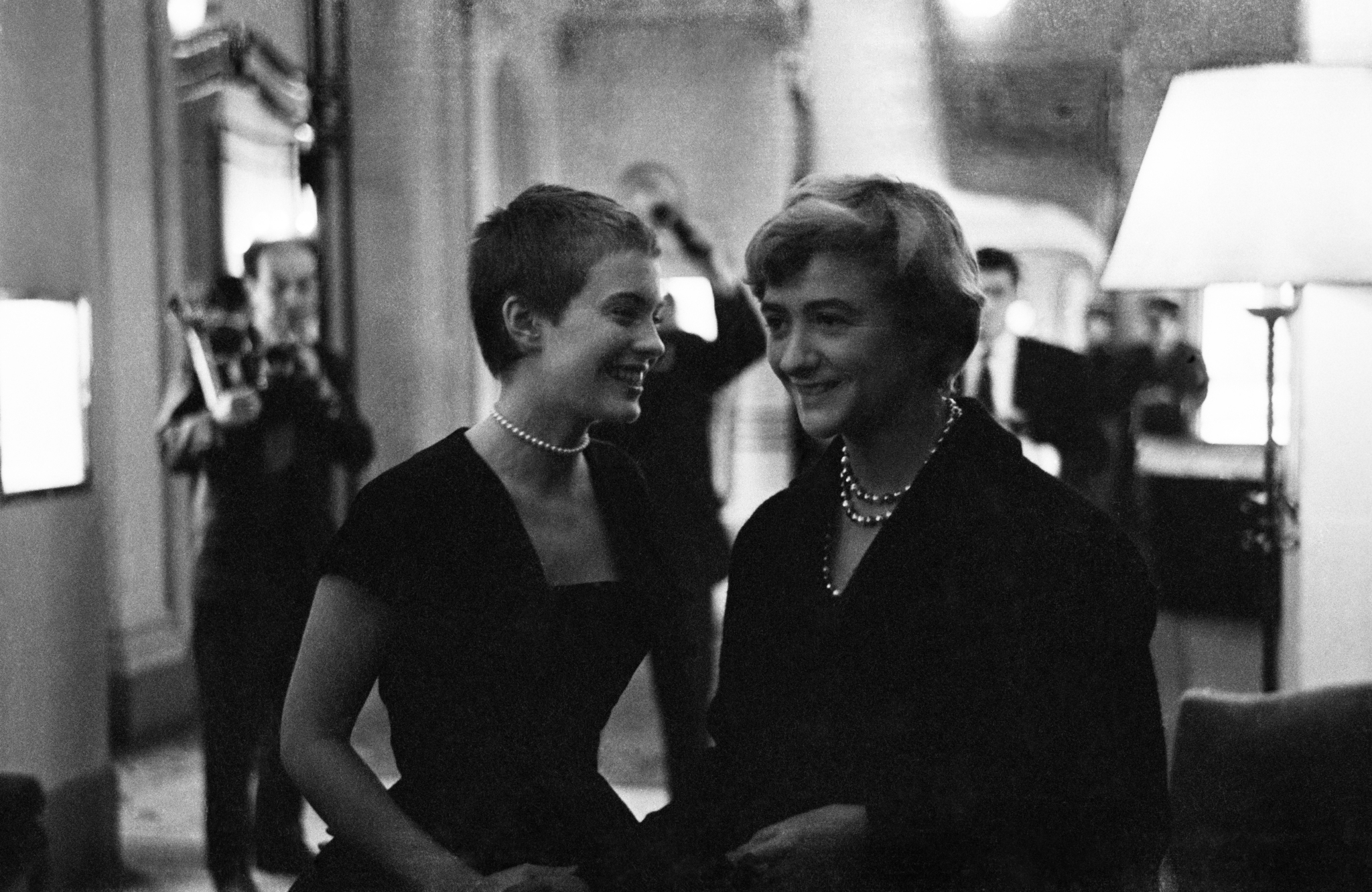

Durga Chew-Bose (middle) with her producers Lindsay Tapscott and Katie Bird Nolan behind the scenes of Bonjour Tristesse. By Marius Müller

“You think of Bonjour Tristesse and you think of Jean Seberg’s face and cropped haircut. But is it Françoise’s haircut you’re thinking of? It’s sort of a mixed-media memory. I’m struck by all of it together.”

Durga Chew-Bose

Food was one of those patterns that developed that I didn’t realise was happening until later. From a practical standpoint, we’re making a film that takes place in a home. So there’s a domestic veneer over everything. Scenes happen in the living room or the kitchen or the dining room. The action takes place around mealtimes. But also, I’ve always found it so interesting and very simple things they do can really explain who someone is at a core level—the way the women eat an apple in a different way. But what someone might notice about someone else is what interested me more. Are we experiencing it through Cécile’s memory? Anne is so elegant with butter and Cécile is more feral and efficient. That juxtaposition is funny to me. My sense of humour isn’t bombastic, it’s more quiet. Stuff like that I find enjoyable.

All the books you see on screen are fake. There’s one called Claudia Claudia with a pink cover. I asked my friend, Teddy Blanks, who worked on our titles, to design fake book covers for me, so all the characters could read them. All the book covers are figments of my imagination. But they’ve got Easter eggs in them, like Claudia Claudia is the name of a Monica Vitti character. Anne is reading a book written by E. Yang because Edward Yang was a filmmaker that my cinematographer and I would revisit a lot. They made up titles and fake copies and blurb on the book. It was a fun creative project, but also it was done for practical reasons. I didn’t want the audience to fixate on—well she’s reading the new Sally Rooney book or something. I felt we weren’t making television so I just wanted to continue a timeless vision for the film.

I read a lot of stuff about Françoise Sagan. Everything extra I could find about her life. I loved her ability to squander all her money and gamble it away. Her need for speed. She raced cars and had bad car accidents. And there’s an accelerated way of living that I found so opposite of her. But it also made her a celebrity. Her son Denis Westhoff was very closely involved in our film. He’s an executive producer and visited sets, and has been really involved and loves the film. I think that added a layer to all of this that was really important to myself and my producers. Denis kept on saying that his mother would have liked this new version. But it wasn’t just his blessing. He was in some ways a vessel, bringing us closer to his mother. I kept her in mind, and in these weird, magical ways. When we cast Nathalie Richard, an actor I admire and love, as Cyril’s mother, there was a moment when someone was like, “She looks like Françoise!” I felt that Françoise Sagan was there.

Foot Note

Born in 1935 as Françoise Delphine Quoirez, Françoise Sagan borrowed her nom de plume from Princesse de Sagan, a character in Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. The title of Bonjour Tristesse—which she wrote at the age of 18—comes from the opening lines of Paul Éluard’s poem À peine défigurée. “I simply started it. I had a strong desire to write and some free time… This is the sort of enterprise very, very few girls of my age devote themselves to,” she told the Paris Review in 1956. “I wasn’t thinking about ‘literature’ and literary problems, but about myself and whether I had the necessary willpower.”

Foot Note

Born in 1935 as Françoise Delphine Quoirez, Françoise Sagan borrowed her nom de plume from Princesse de Sagan, a character in Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. The title of Bonjour Tristesse—which she wrote at the age of 18—comes from the opening lines of Paul Éluard’s poem À peine défigurée. “I simply started it. I had a strong desire to write and some free time… This is the sort of enterprise very, very few girls of my age devote themselves to,” she told the Paris Review in 1956. “I wasn’t thinking about ‘literature’ and literary problems, but about myself and whether I had the necessary willpower.”