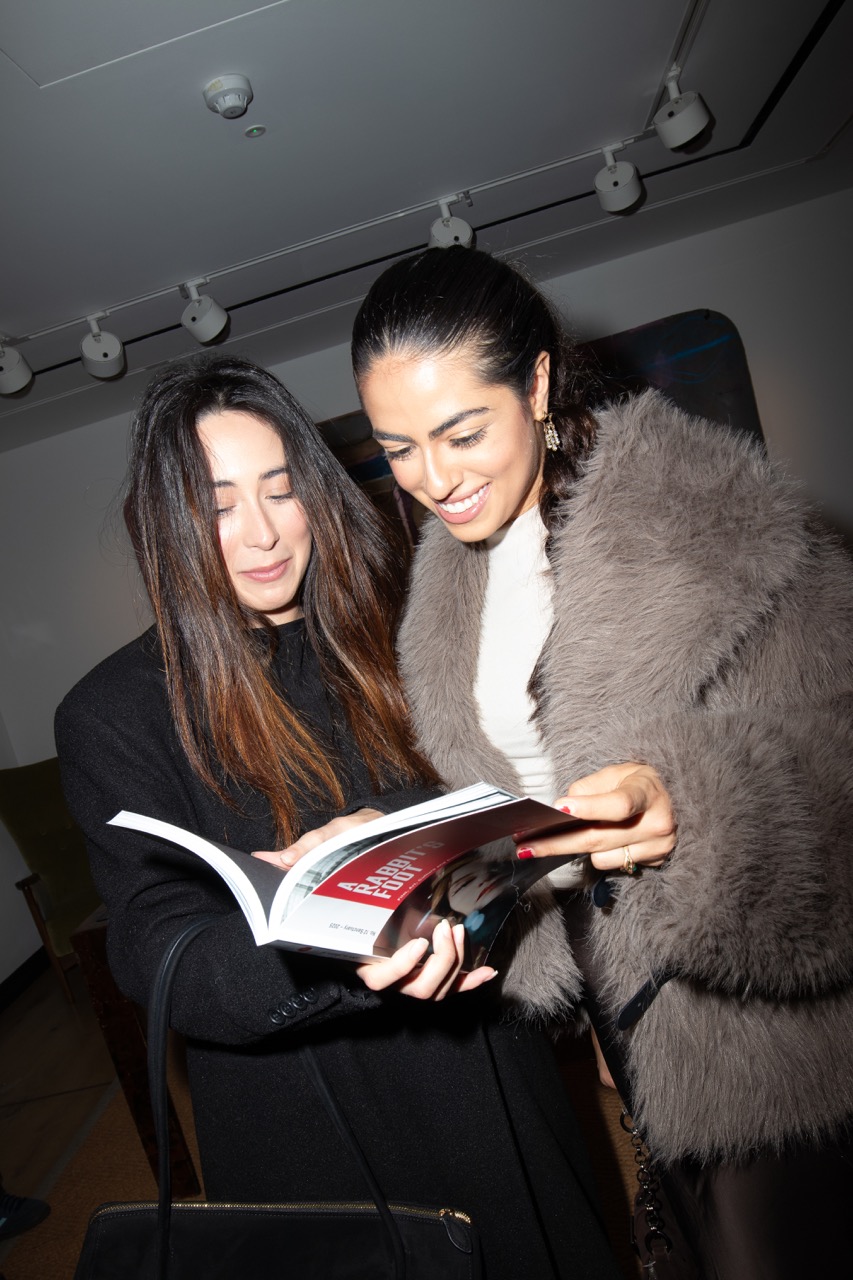

For the final Paul Smith x A Rabbit’s Foot salon, Genevieve Gaunt sat down with our Editor-in-Chief for a conversation about his multi-faceted life and career. Photography by Charlie Pike.

Both a quintessential Londoner and Hollywood impresario (by way of Jamaica), the texture of Charles Finch’s life and career is woven from the silver threads of film, fashion, stars & style. A life of pedigree but no silver spoon, Charles is the grandson of alpine legend & groundbreaking chemist George Ingle Finch and the son of actors Peter Finch and Yolande Turner (nee Turnbull).

But there’s an olive missing in this martini…Parties. Back in 1984, Charles threw an impromptu Hollywood party at Mr Chow’s restaurant. It was small but Warren Beatty, Al Pacino, Sharon Stone and other legends showed up. Decades later Charles Finch and Chanel have thrown countless Oscar and Bafta soirees so glamorous that, as Harper’s Bazaar put it, ‘even the stars get starstruck’.

A self-described ‘creative entrepreneur’ and film producer, Charles founded Finch & Partners in 2000, Chucs restaurants in 2011 and recently co-founded the luxury shoe-brand Équipement De Vie. In 2022, Charles founded A Rabbit’s Foot and recently A Rabbit’s Foot Films which has a first look deal at Sony’s Columbia Pictures. He sits on the board of MUBI and has published two books with Assouline, The Night Before Bafta and this year, a book about style called London Chic.

GG: Charles, Many people know who your father was, the great actor Peter Finch. Can you tell us about your grandfather?

CF: My grandfather George Ingle Finch was a great alpinist, elected President of the Alpine Club in ‘59 and a soldier. George wrote one of the most important books on mountaineering called The Making of a Mountaineer. In the trenches he brought down a zeppelin with a flare gun. He invented the first down-filled jacket and created a felt shoe for climbing Everest in 1932. He revolutionised oxygen for mountaineering at high altitude for which Hillary and Tenzing then used for their second ascent and victory on Everest. George was a really interesting entrepreneur. Not interested in money. He had a sartorial elegance but he was a pretty tough man. His son Michael was probably one of the most decorated wing commanders in the Second World War. We are a mismatched but ancient sort of Viking (Ingle) and Saxon (Finch) family. A family of wild, outdoor men and beautiful women.

GG: Years ago was there a biopic going to be made about your grandfather, George Ingle Finch, starring Tom Hardy…

CF: Yes, it’s still around. Doug Liman. Now, it’s Sam Heughan currently attached to play George. My grandmother, Betty, was a wild socialite in the 20s. She had a great fondness for champagne and young men so my grandfather questioned whether their boys were really his sons. This led him to abduct my father and sent him to my great aunt in Australia. Because of that scandal, George was then banned from the Everest expedition which turned out to be the fatal expedition where Mallory lost his life.

GG: What was your childhood like? You had to overcome quite a lot.

CF: In comparative terms, yes. My mother was a very beautiful young woman and she met my father on a beach in Africa. They had this tumultuous love affair. But my mother was cut off from her family for marrying an actor. And, worse, an actor who had some ‘Australian connections’.

My father, Peter Finch, was a matinee idol of the time and made all of these extraordinary movies like Sunday Bloody Sunday – a powerful film and the first time a man kissed another man on screen. Far From the Madding Crowd and Network. He won 5 Baftas, 2 Academy Award nominations and then won a posthumous Oscar for Network.

His friends were actors like Peter O’Toole and Richard Harris. They had this incredible free life compared to actors today. They could really act and work and not be photographed and shamed for any bad behaviour.

My mother and my father divorced when I was four years old and I only saw my father once again. He abandoned the family. There was no doting in my time. I heard on the radio in a taxi in Paris that my father had died. I was 13. So the destruction of the family was pretty intense. Life changed.

GG: Where was home as a child?

CF: I’ve lived in many places. When mother and father got married they headed for Jamaica and built a little house and farm in a place called Bamboo in Saint Ann. That was home. Every time things got tough in my life, I would figure out a way of getting back to Jamaica. In my heart, Jamaica is my compass; later, The Bahamas.

GG: You went to Gordonstoun. Was it a happy time?

CF: I loved Gordonstoun. It was a fantastic experience for me because you could be outside; go fishing. There were girls who arrived at the end of my first year, which was marvellous! Women balanced the school.

GG: You nearly had to leave?

CF: I was 15, and the Bursar said, ‘Look, the way that school works is that you have to pay the bill’. And then the film producer John Brabourne, amazing man, came along and got me a scholarship. And that’s how I finished school.

GG: You became captain of the rugby team and then Head Boy…

CF: After Gordonstoun, I did a parachute training course and realised I was really not Royal Marine material. I came down to London and I got a job at a stockbroking firm. I lasted six months. Then I became a nightclub bouncer at an exclusive members’ club called Tokyo Joe’s. If I was on the door, things could be arranged…. But I knew I really wanted to be in film and so got an interview with David Puttnam who was producing Local Hero. I said ‘I’ll do anything!’ and became his third assistant. My job was to make tea and amuse Burt Lancaster and his wife and feed people. And that’s how my career in the movie business started. I winged my way to New York and went to Lee Strasberg’s Actor’s Studio.

GG: When you first landed in LA, where did you stay?

CF: I headed for the Chateau Marmont. On my first night I went to the bar downstairs and I met a producer called Noel Marshall. He’d produced The Exorcist. He was quite an eccentric but kind man. And he said, ‘what are you doing here, kid?’ And I said, ‘Well, I wrote a script and I’d like to learn how to make movies.’

Noel said ‘okay, well I’ll give you a job. Come to my house tomorrow.’ I was very excited. I asked Sheila ‘is this guy kinky or anything like that?’ She said ‘No, he’s married to Tippi Hedren and you should go and see him’.

With $365 I bought a white convertible VW Beetle called Myrtle. I loved that car. I had parked it outside the Chateau Marmont but the next morning somebody had stolen the roof of the car; unscrewed it! I got to the top of Mulholland Drive and came to this big gated property with wire mesh and lots of lights like a prison camp. I rang the bell and the housekeeper said ‘Don’t leave the car! We’ll come and get you.’

So the gate opened and closed behind me, then another gate opened and closed behind me. I thought, my God, where am I going here? I was nervous. I sat in the car thinking ‘they must have big dogs.’ Then bushes started moving. Then I saw this big shadow come out of the bushes and it was the biggest lion you’ve ever seen in your life. Enormous lion. It was Elsa from Born Free. She leant against the car. And then Elsa’s friend came and leant against the car. Tippi and Noel kept lions in their house. They’d made a movie called Roar. And there I was surrounded by lions, with no roof. I got a job at $500 a week and that started my movie career.

GG: You shared a house in LA?

CF: I stayed in Damien Harris’ house. His father Richard Harris was a great friend of my dad’s. Damien had other people living in his house: Julian Sands, Rupert Everett, Jimmy Spader, Sean Penn, John Malkovich… We lived as a community of young artists. So if any of you are young artists I encourage you to be with your peers. No money. We hustled. I’d cook for people.

GG: What did you cook?

CF: Couscous.

GG: Just couscous?

CF: I can do dry couscous, can do wet couscous, or vegetable couscous. I was literally game for anything to survive. My mum was also broke, so she had moved to California as well, and she wanted to be a screenwriter. We would literally collect coins, because we were fucking broke all the time. That was a driving force. She was such a beautiful woman.

GG: You have her bottle of Chanel No.5 on your desk…

CF: It always makes me very sad. Her struggle. We wrote a movie together called Bad Girls – a female western with Madeleine Stowe, Mary Stuart Masterson, Drew Barrymore, Andie MacDowell and a young director who was fired pretty quickly… We managed to sell it to Fox and we made that movie and another couple of movies. It did quite well at the time, made about $60M. A big deal then.

GG: Can you tell us about the link between Chanel, your mother, and making the movie with Sharon Stone?

CF: I’d written a series of movies called The Dentist, The Dentist 1, The Dentist 2, and The Dentist 3. I was like 22. And they were really, really bad. But they got paid quite well, and they were quite successful. So all of a sudden, I kept getting called by these kind of famous producers. ‘Hey, you wrote The Dentist? Do you want to write The Doctor? Do you want to write The Sister? The Nurse?’ For two years I couldn’t get away from the horror medical genre.

Aged 25 I wrote and directed my first film, Priceless Beauty, shot in Italy with Diane Lane and Christopher Lambert. The second movie I made was called Where Sleeping Dogs Lie. There was an actress who was doing pretty well called Sharon Stone. She was fine on the eye and she had something very fierce about her and so I cast her. I was on a plane and in front of me was Karl Lagerfeld and I tapped him on the shoulder and said, ‘Listen, Mr. Lagerfeld, I think my mother used to be a big client of yours. Would you dress this actress in my movie?’ He was so kind and open and intrigued. He said ‘Yeah, okay, call my office’. In the movie Sharon Stone was swathed in Chanel. That’s how the relationship started.

My third movie as a writer-director was called Never Ever. I’m also in the movie and not a very good actor, but it was hell of a good time because I fell in love with the leading lady, Sandrine Bonnaire. But, I realized after that movie, which opened the Toronto film festival to disastrous reviews, ‘maybe I shouldn’t do this anymore’. That was a mistake.

For those of you listening to this, hearing this: keep going because a lot of great directors have made lots of bad movies. I know if you’ve seen Rebecca Miller’s documentary about Martin Scorsese, it’s a great documentary. Scorsese talks about failure, talks about the movies that didn’t work and all this stuff. You just got to keep on going.

GG: You switched sides and became an agent at William Morris?

CF: I was broke and needed a job. I love agents. I think agents get a bad rap because first of all they’re trying to help somebody have a career. And they don’t get paid enough.

GG: You had some amazing clients. Who did you represent?

CF: John Malkovich, Willem Dafoe, Harvey Keitel, Cate Blanchett and so on… American agents are incredibly entrepreneurial. They can see 50 different opportunities for their clients.

Ernest Hemingway suffered from enormous anxiety so in his pocket, he carried a rabbit’s foot for luck.

Charles Finch

GG: How did getting stars doing luxury campaigns start?

CF: I figured out that there was all this downtime for big artists where they weren’t making any money. So I thought ‘let’s go to the brands and have them pay for stars to wear clothes or carry handbags’. It’s expensive being a movie star. You have security and protection and it’s not a nice job by the way. It sounds like a nice job, but actually it’s a fucking horrible job because everywhere you go you can’t be normal. Especially today where you can be so easily shamed and criticized. Stars doing luxury campaigns meant they could turn down bad movies and make more creative choices. We would be very selective. Unless it was in Japan. In which case back in the day nobody would know.

Then I made the fatal mistake of agreeing to head up William Morris internationally. We had 9 offices internationally at that time. And so I left California. Big mistake. The movie business was really centred there.

GG: Is that how Finch & Partners came about?

CF: I figured William Morris could turn into a producer itself. But they said ‘that’s not our business’. So I left and started Finch & Partners.

GG: Style links all of the different areas of your life and career. Do you ever wear a tracksuit?

CF: Yes, when it’s appropriate I do wear a tracksuit but I think people have taken the relaxed dress to the point of ridiculousness now…

GG: Where do you get your suits?

CF: I have an Italian chap in Naples called Elia Caliendo. And Paul Smith makes amazing things. I’m a fan of Sir Paul. He’s the only British designer to really have conquered America and remained independent.

GG: And you co-founded a shoe brand, Équipement De Vie?

CF: Yes. When you sell boats you have to have sole grip. Prada grip shoe costs you about £800 pounds and our grip shoe costs you £140 pounds.

GG: And if you’re shipwrecked…

CF: You can eat the shoe! The midsole is made using 35% sugarcane.

GG: You mentioned your restaurant, Chucs. When is Bar Finch opening?

CF: I’ve always been interested in food… beyond couscous. And my new restaurant is called Bar Finch, which is opening in Mayfair next year.

GG: Harvey Keitel famously called you…

CF: ‘Champagne Charlie’. There’s a reason for that… at Lee Strasberg’s Actor’s Studio there were these amazing actors around like Pacino, De Niro, Keitel. Harvey used to say to me, ‘for a kid who’s broke, you certainly dress well, I like those loafers and stuff.’ Keitel started calling me ‘Champagne Charlie’ because every time I had any money, I would take us all out to dinner and order a bottle of champagne. It’s a bit like a Russian philosophy, kind of like Stanislavski’s as well, which is: you could be dead tomorrow so you’d better live.

My other passion obviously is literature and publishing. For 5 years I published a magazine called Finch’s Quarterly Review edited by a brilliant guy called Nick Foulkes. And now I have this, A Rabbit’s Foot on its 14th issue .

GG: Advice for people in business?

CF: You have to have a very strong idea of what exactly you’re doing. Why are you doing this and what is it? And you need people to sell. You can make beautiful things but if nobody sees them then it doesn’t matter. And ‘repetition is reputation’. You just got to keep on going.

GG: How has business changed?

CF: I think we live in an oligarchy today where the rich have too much dominance in politics and every part of lives. You can lose money if you’re investing infrastructurally to grow. There are lots of businesses today which are not sound and are overvalued. AI may be one of them. A huge amount of money has been written off recently in the AI markets.

My team has the same philosophy as me. The responsibility of old-fashioned business engineering where you’re concerned with making profit is how I run my businesses. And that may not be chic and that may not be of its currency, but my business has been going for 28 years and all around me I’ve seen businesses collapse. Big businesses, small businesses.

GG: Advice for young creatives?

CF: If you do nothing else- just read. You learn so much and it’s so inexpensive to read. My personal survival mechanism is to write. Worse comes to worse, I’ll always figure out a way of writing myself out of hell.

GG: If you had to choose one of the things you’ve done over the past 40 years what would it be?

CF: Directing movies is the most incredible job. Great directors have huge impact on the currency of conversation, social currency. It’s hectic but fabulous. Producing movies is a big pain in the ass but worth it if the story needs telling. Publishing is also an amazing creative undertaking. I didn’t sort of come out of the womb to be a polymath. It wasn’t my big plan to like to do 10 different things. It was through necessity that I had to constantly adapt and contrive to make other businesses happen so that I could have freedom and independence. And so that’s why I do all these things is to be free, to not have a boss. I like that.

GG: Rabbits are a lucky symbol for Paul Smith…Where does the title, A Rabbit’s Foot, come from?

CF: Ernest Hemingway suffered from enormous anxiety so in his pocket, he carried a rabbit’s foot for luck. And I have a gold rabbit made by the artist Suzy Murphy… For luck.